What does the empirical literature say?

In a recent Washington Post article, Treasury Secretary Snow was quoted as follows:

Speaking to the International Monetary Fund, Snow repeated the U.S. position that ratcheting down big imbalances in trade and capital flows “cannot be anything other than a shared responsibility” because no one country caused them.

Interestingly, this assertion is much less nuanced than the Treasury Occasional Paper on the subject released at roughly same time. That study cited point estimates for the response of the current account to GDP ratio to a a budget balance to GDP ratio ranging from 0.1 (Erceg et al.) to 0.44 (IMF).

Since the study also cited the 0.13 coefficient Chinn and Prasad (2003), it seems only natural to discuss what Hiro Ito and I have discovered in our updating of these estimates to 2003 (the previous estimates pertained only up to 1995), coming out in a forthcoming revision of our paper here. The updated point estimate is 0.20 — for a pooled panel cross section regression (where the observations are 5 year averages of annual data).

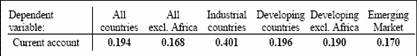

Our fixed effects regression estimates for different sets of countries is presented below:

Estimated coefficients on the government budget balance (% of GDP) in the fixed effects regressions. Source: Chinn and Ito, forthcoming revision of Current Account Balances, Financial Development and Institutions: Assaying the World “Savings Glut”

The critical estimate for this discussion is the industrial country point estimate of 0.40. The estimate is significantly different from zero at the 10% marginal significance level. Why is this point estimate so different from the pooled panel-time series estimate? The biggest impact likely arises from allowing each individual country to have a different constant, something ruled out in the pooled OLS procedure. (In addition, the simple pooled OLS estimator treats the errors as having the same variance over all the individuals).

Is the pooled estimator appropriate? It depends upon the question one is asking. If one wants to know something about the average response for an industrial country’s current account balance to changes in the budget balance, assuming a high degree of homogeneity across the countries, then this is the correct number. If, on the other hand, one is interested primarily in how the United States behaves, allowing it to have a country specific constant, then the fixed effects estimate is more relevant. Hence, in my mind, the question of whether fiscal policy would be effective in reducing the current account imbalance of the United States is an open one, and using more recent data, I would assert the empirical evidence — as opposed to calibration-based results — is on the side of effects greater than 0.2. (Moreover, in a series of robustness tests, using instrumental variables, the Arrelano-Bond GMM approach, and detrended data using Hodrick-Prescott filters, we have obtained estimates ranging from 0.22 to 0.40).

As I have noted elsewhere, when the coefficient is 0.4 (remarkably close to the OECD’s Interlink model, and similar to that in other estimated macroeconometric models), 0.4 means that a 6% percentage point swing in the budget balance — like the one that took place after 2001 — would result in a 2.4 percentage point swing in the current account balance. Not enough to eliminate the deficit, but certainly enough to make a substantial impact.

Technorati Tags: budget deficits,

current account deficits,

twin deficits,

global imbalances

Menzie Chinn on the Budget and Current Account Deficits

Following up on this post on the twin deficits, here’s Menzie Chinn of econbrowser: The Debate over the Impact of the Budget Deficit on the Current Account Deficit, by Menzie Chinn:What does the empirical literature say? In a recent Washington

http://www.economist.com/countries/Japan/profile.cfm?folder=Profile-Economic%20Data

Japan’s got a budget deficit of over 7% of GDP and yet a current account surplus of over 3% of GDP. I don’t know the exact numbers for Germany, but it also has a hefty budget deficit and yet a substantial current account surplus.

For that matter, without bothering to look up the numbers, I seem to recall that the 1990 recession exploded the US budget deficit while simultaneously lowering the current account deficit to next to nothing,

and the late 90’s boom resulted in a budget surplus but didn’t exactly do much good in reducing the current account deficit.

Yes, and there are also many examples of countries that have budget surpluses and still have current account deficits that are as large (Spain) or even larger (Estonia, Iceland and New Zealand) relative to GDP than the U.S.

Yet all this really shows is that there are other factors than the budget balance that determine the current account balance. Indeed, one independent factor (the business cycle) will act to push the budget and current account balance in opposite directions, increase the budget deficit and lower the current account deficit during recessions while reducing the budget deficit and increasing the current account deficit.

Yet this does not take away the fact that other things being equal, moves to reduce the budget deficit through tax increases and/or spending cuts

will reduce the trade deficit.

That the statistical correlation is imperfect only goes to show (again) that you will never find any perfect empirical correlation between any one causal factor and a phenonema when there are more than one causal factor co-determining this phenonema.

Heiko Gerhauser and Stefan Karlsson: Both of you make good observations. Indeed Economist’s View has an excellent post (which I should have referenced before) discussing when the budget and current account balances should covary. When shocks are primarily fiscal in nature, the theory implies covariation; when the shocks are exogenous (e.g., investment/animal spirits, or monetary policy driven), then one can a different covariation. We attempted to address the business cycle effects by using time-averaged data. In the upcoming revision, we HP-filter the data to remove business cycle effects, and obtain a significant estimate for this coefficient. (And just to be explicit, if you haven’t checked out the paper, we do have many control variables in our multiple regressions.

Stefan–the Icelandic crown and the NZ dollar have taken a hit this year already. We might be waiting for an even bigger shoe to drop–the biggest one of them all–Uncle Sam’s!

Dr. Chinn, from what I remember of multiple regression, you can check the variance inflation factor (VIF) or tolerance for excess covariance. Did you get indications of high VIFs? Your model is almost heroic, but the VIF might be something to look at.

The US can easily choose to balance the budget in a manner that’s going to hit the current account, for example by taxing the oil industry to the point of making domestic production unviable, or by reducing farm subsidies to the point where the US becomes a net food importer.

The US can also easily balance the budget in a manner that gives a much higher coefficient than 0.4, eg by cutting direct transfers. That’ll cut the CA by 1 Dollar for every Dollar less given in foreign aid.

Emmanuel: We haven’t used the VIF to determine whether multicollinearity is a problem. We know some variables are correlated from experience, but none are highly correlated (except, for obvious reasons, some of the interaction terms). A bigger problem is that the sample is reduced in different ways when different variables — especially institutional and some financial development ones — are included.

Heiko Gerhauser: You’re right that the composition of deficit reduciton matters. However, even if reduction in spending on goods and services (as opposed to transfers) is the mode by which the budget deficit is reduced, the change in the budget deficit is not dollar for dollar. In addition, the effect on the current account depends on the private sector response (sometimes called “the offset” in the jargon).

I don’t understand why you say “even if”. I never said that if a reduction in spending on goods and services were the mode by which the budget deficit were reduced, there’d be a 1 for 1 reduction in the current account.

What I was arguing was that a Dollar of deficit reduction could have a coefficient ranging from -infinity to +infinity in terms of its effect on the current account.

In the specific example of a government transfer, where the US government gives a Dollar of aid in the form of treasuries to a foreign government and that foreign government then sits on those treasuries, we have a coefficient of exactly 1. 1 Dollar of extra aid gives exactly 1 Dollar of extra current account deficit and exactly 1 Dollar of extra budget deficit.

If the foreign government doesn’t sit on the aid, but instead is forced to spend it on US goods or services, the coefficient is no longer 1. In fact it may be less than 0, say if the foreign government is forced to spend the Dollar on Microsoft software, and Microsoft managed to leverage that into an extra 10 Dollars of foreign sales.

I think that the value for the coefficient of 0.4 you calculated must be seen in that context. Specific, actual budget deficit cutting measures will have a wide range of coefficients ranging from less than -1 to more than +1.

Tax/spending policy doesn’t just affect aggregate domestic demand, but also the relative competitiveness of foreign and domestic producers and the efficiency of the economy. There are measures that’ll raise domestic demand, but raise domestic productive capacity by even more (arguably opening ANWR would be such a measure), and others (outlawing all drilling of any kind anywhere with immediate effect say) would cut domestic demand, but cut domestic productive capacity by even more.