Quantification is the first step in assessing the proper course of action

In some previous posts (e.g., here), I have argued that the energy policy (or lack of policy) pursued by particularly this Administration has worsened the trade deficit.

Source: Author’s calculations based on Jan 2006 NIPA release.

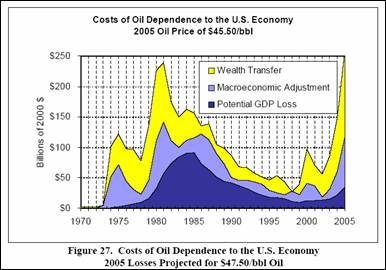

A more comprehensive, wide-ranging, quantitative assessment of the costs of energy dependence is complicated by the fact that there is some dispute over key parameters (substitubability of capital for energy, price rigidities, etc.). Nonetheless, the Oak Ridge Laboratories have undertaken a study (Costs of U.S. Oil Dependence: 2005 Update) assessing the output, potential GDP, and wealth transfer costs. The document’s summary states:

“[T]his report focuses on its direct economic costs. These costs are the transfer of wealth from the United States to oil producing countries, the loss of economic potential due to oil prices elevated above competitive market levels, and disruption costs caused by sudden and large oil price movements. Several enhancements have been made to methods used in past studies to estimate these costs, and estimates of key parameters have been updated based on the most recent literature. It is estimated that oil dependence has cost the U.S. economy $3.6 trillion (constant 2000 dollars) since 1970, with the bulk of the losses occurring between 1979 and 1986. However, if oil prices in 2005 average $35-$45/bbl, as recently predicted by the U.S. Energy Information Administration, oil dependence costs in 2005 will be in the range of $150-$250 billion. Costs are relatively evenly divided between the three components. A sensitivity analysis reflecting uncertainty about all the key parameters required to estimate oil dependence costs suggests that a reasonable range of uncertainty for the total costs of U.S. oil dependence over the past 30 years is $2-$6 trillion (constant 2000 dollars). Reckoned in terms of present value using a discount rate of 4.5%, the costs of U.S. oil dependence since 1970 are $8 trillion, with a reasonable range of uncertainty of $5 to $13 trillion.”

Under a wide number of assumptions, the costs of energy dependence in 2005, given a price of oil of $45.50 per barrel, is estimated to be about 250 billion 2000 dollars.

Figure 27 from Greene and Ahmad, “Costs of U.S. Oil Dependence: 2005 Update,” Oak Ridge National Laboratories.

The actual average price in 2005 for WTI was $56.5 so this is an understatement (at least based on these assumptions). For perspective, the US real GDP in 2005 was 11.1 trillion 2000Ch. dollars.

Of these costs, the ones that rely least on contentious parameters is the wealth transfer — essentially how much is transferred to foreign oil producers (although a guess about the competitive price needs to be assumed). Here, the figure is about 150 billion 2000Ch., or about 1.4% of GDP.

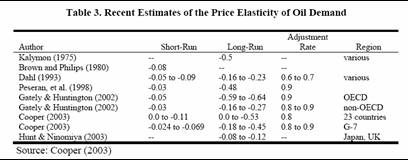

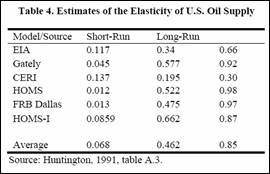

I found the survey of price elasticities interesting in their own right. The report presents two tables.

Table 3 from Greene and Ahmad, “Costs of U.S. Oil Dependence: 2005 Update,” Oak Ridge National Laboratories.

Table 4 from Greene and Ahmad, “Costs of U.S. Oil Dependence: 2005 Update,” Oak Ridge National Laboratories.

What I found most interesting is the relatively high (at least compared to what some people think) long run price elasticities of oil demand, combined with relatively low long run supply elasticities (the typically cited figure is slightly lower than the average here, 0.3, which is close to the EIA figure). This suggests to me that there is considerable scope for reducing demand via taxes, while attempting to increase domestic supply by way of subsidies would be more difficult (note that the average rate of convergence to the long run is lower on the supply side).

Obviously, this doesn’t mean we should seek to set oil imports to zero. But it does mean that there is a cost to relying upon energy, and additionally (my focus here) to relying upon imported energy. We should seek to reduce energy imports using as a guide economic principles — namely investing in conservation R&D, and implementing taxes, up to the point that the combination of instruments leads to the internalization of negative externalities. Here we have not only the environmental ones, but also those associated with additional variability in income (after all, in a Taylor rule world, variability is a bad thing). And then there is the question of whether we would need to be so monomaniacally obsessed with oil supplies — and hence need to sacrifice so many resources to maintaining large ground forces in the MidEast — if we were not so susceptible to such large terms of trade shocks.

Technorati Tags: energy dependence,

oil price elasticity

I am greatly puzzled: ca = s(n) – inv. Energy policy per se has little to do with this.

Furthermore, it is not clear to me that there is a pressing need for the government to “solve” the problem (other than carbon taxes). Well, perhaps it should push for nuclear energy, i.e. stop caving to environmentalists who appear to desire (effectively) a return to the stone age.

randy: Let me rewrite in order to make this explicit. CA == (T-G) + (S-I) + V where T is taxes net of transfers, G is government spending on goods and services, S and I are private sector savings and investment respectively, and V is net factor payments as well as transfers. “==” means “true by definition”. Well I in neocassical models depends upon the user cost of capital which must depend upon the rate of economic depreciation, which is often interpeted as being a function of changes in energy prices when those change quickly. S in the medium to long run may not depend on energy (although this must depend on homotheticity assumptions, and how transfers to the rest of the world due to higher energy prices affect income), but will in the short run. In the short run, with Keynesian or New Keynesian type rigidities, combined with highly inelastic short run demand for oil, increases in oil prices should surely affect the trade balance. So the national income accounting identity you put up there is not incorrect (I use it teaching intermediate macro all the time); rather, I would say it doesn’t highlight the channels through which changes in energy prices would affect output — and in any case, identities don’t say which way the direction of causality goes. (By the way, drastically higher energy prices are usually thought to reduce the effective capital stock, thereby reducing potential output. To the extent that reduces the present discounted value of “net output” into the future, this should improve the current account balance in a frictionless optimizing infinite-lived agent world, although of course, the net impact on aggregate social welfare is almost surely negative.)

> These costs are the transfer of wealth from

> the United States to oil producing countries,

> the loss of economic potential due to oil

> prices elevated above competitive market

> levels, and disruption costs caused by sudden

> and large oil price movements.

I don’t begin to understand the argument. Obviously all imports have to be paid for, and paying for them is going to involve a transfer of wealth. So? Think how much money we would all save if we never bought anything. The last two points are even more mysterious to me. Why does Oak Ridge think that domestic producers would not be just as quick to take advantage of the market opportunities as overseas producers?

Because American oil producers are nicer? That must be it.

Help me understand. If supply and demand have driven up oil prices, how does the government help by adding a tax on top of that?

Increasing taxes on energy will certainly put pressure on demand, but will the reduced usage of energy actually be good for us? Fewer trips to see family and higher prices of trucked goods hardly seem like benefits to me. Is this an example of “I’m from the government and I’m here to help you.”??

Unless the federal government decides (like Britain) to use a gasoline tax TO REPLACE an existing tax, such a tax would only add billions to the amount of money we squander by the Potomac.

Personally, I think the $2.5 Trillion that D.C. gets each year is more than they deserve.

The only legitimate issue you raise here is the externality due to pollution. I don’t buy that we should tax oil to reduce variability. You could say that about any commodity. Oil is hardly the only thing to have gone up in price lately. If we had a huge copper tax then its variability would be reduced as well. That doesn’t make it a good policy.

Plus we don’t even know for sure that we have entered an era of increased variability. You should be able to look at the commodity markets and estimate future variability from option prices, and compare it with previous variability. Last time I saw that done they looked about the same.

If we want to do a carbon tax, here’s how I’d figure it. Presently carbon is accumulating in the atmosphere at the rate of about 4 Gt/yr. That’s about 2/3 ton per person per year, worldwide (actually in the West it’s about an order of magnitude larger). This paper looked at over 100 studies which estimated the marginal cost of carbon-caused global warming:

http://www.uni-hamburg.de/Wiss/FB/15/Sustainability/enpolmargcost.pdf

The median value was $14/tC. This means that a neutral carbon tax would be about $10/person per year worldwide, or in the West maybe close to $100/person/year. Of course these estimates are extremely rough and more research is needed.

It’s also possible that late 21st century technology may be able to mitigate the damage at far lower costs. This paper from Livermore Labs proposes the use of stratospheric particles to block UV radition enough to counter the greenhouse effect. Costs are estimated at only a few billion a year and will probably be much cheaper with circa 2050 technology. In that case a $14/tC energy tax will turn out to have been far too high.

http://www.llnl.gov/global-warm/148012.pdf

“And then there is the question of whether we would need to be so monomaniacally obsessed with oil supplies — and hence need to sacrifice so many resources to maintaining large ground forces in the MidEast — if we were not so susceptible to such large terms of trade shocks.”

Large ground forces are necessary in the Middle East to deter conflict between a number of potential combatants in the region. Oil is only one factor. Even if the US didn’t need it, it would be in our interest to prevent such wealth from falling into the hands of any Baathist/Stalinist dictator or Sunni/Shia end of times maniac, as well any other evil doers. The need is independent of US consumption. Having said that, any way you twist the energy puzzle, oil will be the life blood of the global economic system for decades to come, no matter what energy policies are pursued. The “we spending all this money in the ME so we can drive SUV’s” theory is simplistic nonsense.

Guest – “Oil is only one factor. Even if the US didn’t need it, it would be in our interest to prevent such wealth from falling into the hands of any Baathist/Stalinist dictator or Sunni/Shia end of times maniac, as well any other evil doers.”

However the implicit assumption here is that we are the good guys. (I am Australian) You are also assuming that it is our oil to protect. Neither of these assumptions is necessarily correct.

First of all our actions in the Middle East are placing us into the realm of evil doers. Torture camps and bombardment of innocent people are not the actions of a saintly society no matter how much you think that they deserve it.

Secondly the oil is the property of the “Baathist/Stalinist dictator or Sunni/Shia” or whoever’s people that live in the country. In places like Nigeria the people remain poor and have high energy prices while we have plenty to drive our 4WDs (SUVs). The US and Australia have both nearly exhausted their reserves of oil. The oil belongs to someone else.

The most significant category contributing to our trade imbalance is #27, mineral, fuel & oil per trade statistics posted at export.gov. In 2005, that amounted to $260 billion. With inflationary pressures continuing to mount, a policy of higher taxes would be more logical given the hazards of raising interest rates. A policy of lower taxation when inflation runs high is economically incongruent. Pick up your 101 textbook if you feel otherwise. Our current policy of raising interest rates to slow economic grow is going to cause great damage to the housing sector. The responsible approach would involve tax hikes. What better than to tax oil? The author’s observations are keenly correct.

So most ignore/miss Menzie’s

Likewise, any move to reduce demand is met with the same mentality that characterizes GM’s hybrid SUV thinking. The heist continues because most people have their houses to spend. So filling the fuel tank is a bearable burden for now. And a pleasure for the oil companies –none of that 55mph stuff for them.

Menzie in your opinion, for how many years

could the ‘occident’ transfer so much wealth

to the oil producer without feeling the consequences?

(sorry for my english..)

What do the Middle Eastern oil producers do with their petrodollars ?

Invest it in America. Hence, the wealth is not transfered it is merely recycled.

for Guest2. May be you are correct but

it would be better if they buy goods and services

fm Usa and Europe instead of merely to invest.

It seems that they are not buying as they do

in the past. In europe we need to

give a job to million of people..if they buy our

goods this will be easier…

Guest2, if (1) we pay the Saudis $1 million for oil, and (2) the Saudis buy a $1 million U.S. Treasury bond, that is $1 million more that we owe to foreigners than we did previously. The more money you owe, the less wealthy you are said to be. So, I believe it is more accurate to describe this as a wealth transfer rather than wealth recycling. Specifically, we get oil from them, and we give them some of our wealth in return.

Randy,

Blaming “environmentalists” is a bit like Rush Limbaugh blaming everything on “liberals.”

There are lots of things preventing wider use of nuclear energy, including lack of permanent disposal for waste and dismantled reactors, liability, and costs that have not proven as attractive as advertised. The public has not been crying out for nuclear energy. Unless the public in general fit into your “environmentalist” category, your assertion doesn’t make sense. If the public does fit in the category, well, welcome to democracy.

Fred,

Oak Ridge may think that domestic producers are less responsive to price than foreign producers because domestic producers have already passed their “Hubbert’s peak.” Can’t squeeze oil from a turnip.

Guest2,

Ownership of wealth changes. The money may come back, but the return it earns does not accrue to US citizens. As is the case whenever one borrows to spend, we are trading spending today against the ability to spend tomorrow.

Y’all are missing the point spectacularly.

Government policy basically sets what sort of infrastructure we’re going to build – which basically decides how oil-dependent we’re going to be, since if, for instance, you spend most of your public dollars and regulatory energy on suburban sprawl, people are going to have to drive a lot. And that road infrastructure lasts a long time – it can’t be easily repurposed for mass transit, for instance. Nor can low-density parking-lot sprawl be easily repurposed into high-density transit-supportive development.

THAT’S where government policy has hurt us; and Clinton was almost as bad as Bush II is – but neither one is really at the wheel here; it’s the House and Senate which set how much money the government is going to spend on roads vs. transit; and it’s your state and local governments which decide how much non-sprawl development their land use codes will allow (usually very little; even today zoning codes effectively outlaw most old-style urban development in most places; requiring suburban sprawl or nothing).