Another way to look at the relationship between productivity and real compensation.

Jim Nason refers me to one of his papers (coauthored with George Slotsve) on fitting dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models to data to assess the empirical validity of various interpretations of the New Keynesian Phillips Curve. Inspired by his results, I generated the following.

Figure 1 is the residual from the cointegrating regression of the log of nominal unit labor costs on an intercept, linear time trend, and log of the GDP deflator using a sample from 1960Q1 to 2005Q4. The residual is economically useful because it peaks between every

NBER dated business cycle peak and trough since 1960. The coefficient on the log of the GDP deflator is 1.08, suggesting an eight percent growth differential between nominal unit

labor costs and the GDP deflator.

Figure 1: Cointegrating residual from log nominal unit labor cost on log GDP deflator, 1960q1-2005q4 (blue), and alternative residual forcing compensation in nonfarm business sector to grow at the same rate as the employment cost index over the 2005q3-2006q2 period. Sources: BLS via FRED II, and author’s calculations.

The data definition of the log of nominal unit labor cost is log( COMPNFB/OPHNFB), using the FRED II mnemonics.

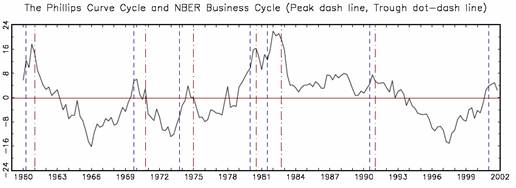

Nason and Slotsve (2005) (linked at this webpage) report similar results for the cointegrating relation of log of nominal unit labor costs and log of the GDP deflator using data that ends with 2001Q4. These authors also show that the residual of this regression can be interpreted as (a multiple of) the business cycle component of real unit labor costs invoking restrictions from the new Keynesian Phillips curve. Consistent with my figure 1, the Nason and Slotsve estimate of the business cycle component of unit labor costs peaks between every NBER dated business cycle peaks and troughs since 1960 (see the bottom panel of Nason and Slotsve’s figure 1).

Figure 2:Bottom panel of Figure 1 from Nason and Slotsve (2005).

Now returning to Figure 1, productivity is indeed growing faster than compensation over the period from the end of the last recession to end-2005. Compensation picks up

in the last year, as evidenced by the shrinking residual. In fact, the residual at 2006q2 is zero. But this is exactly the period during which this graphical depiction becomes relevant:

Figure 3:Tom Toles on labor cost measurement WaPo, Sept. 18..

Or more seriously, as discussed by Mark Thoma, Dave Altig, and as shown below by the divergence between the non-farm business sector compensation and the non-farm employment cost index, it’s not clear how much recent data are skewed by estimates of stock options.

Figure 4: Log compensation in non-farm business sector, 2001q1=0 (blue), and log employment cost index, 2001q1=0. Sources: BLS via FRED II, and author’s calculations.

Assuming that the underlying non-farm compensation is actually growing at the same rate as the ECI, then the residual in Figure 1 (the red line) is still declining — i.e., productivity is still growing faster than compensation. [This last portion is my interpretation, and not necessarily Nason’s or anybody else’s.]

Technorati Tags: productivity,

compensation, and

cointegration.

It seems quite possible that real wages are understanded due to errors in the deflator used (e.g., real inflation has been less). Also quite possible that productivity measurments are off due to the difficulty of accounting for quality increases and new products/technology. So the whole apparent discrepancy might just be a result of measurement error.

Menzi,

Why the cartoon of stock options v wages? As long as stock options are issued at the money it can be the least expensive way for companies to compensate employees and the employees level of compensation will be dependent on the health of the company. A win-win situation. Wages on the other hand are always a cost and usually an inceasing cost.

Dick: The issue is not that whether stock options are compensation; rather the issue is whether we yet have a good handle on how the exercise of options has been handled in the national income and product accounts and in the calculation of compensation of labor. In other words, I’m not certain what’s happening over the last couple of quarters, and further, not certain about the durability of what’s happened according to these statistics.

Wages in a market economy reflect the underlying value of labor. The recent cries that wages are not keeping up is at best confusing for one who has studied economics. The logical conclusion from the data appears to be quite simple – the value of labor in recent productivity gains is marginal. The real source of productivity gains is a function of capital, technology and management. The average blue collar worker in the US is more than well paid on an international basis.

I would suggest that instead of looking at this problem as a paradox we look at it in its simplest form. Markets and companies are allocating resources and rewards relative to their return. Labor is playing a deminishing role in the rise of productivity in the US. This should not be surprizing to anyone who works in a company of any size. Technology is quickly boosting productivity not labor. Why would labor earn a growing piece of the profits it they are not materially contributing to the gain?