If you end up being surprised by the big story of the next decade, you can’t say, “nobody told us.” Instead you’ll have to say, “we didn’t listen.”

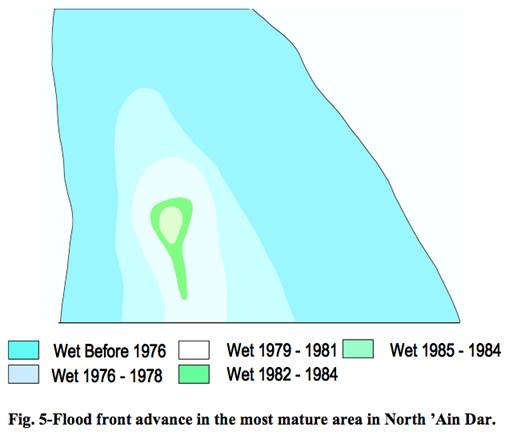

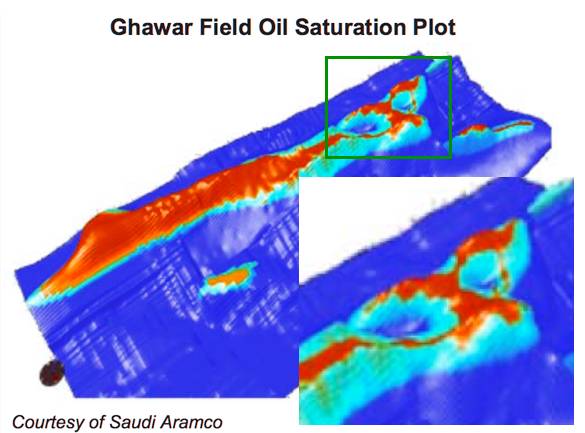

Stuart Staniford (Ph.D. in physics) has been conducting a very careful and detailed investigation of all that is publicly known about Ghawar in Saudi Arabia, which is by far the world’s largest and most important oil field. This field has been managed by injecting water below the oil, which causes the remaining oil to rise toward the top of the reservoir where it can be more readily pumped out. The following diagram is an example of the kind of evidence Stuart has looked at to determine how high the water level was at different locations and different points of time. The figure comes from a Society of Petroleum Engineers study, and shows the location of the oil water contact at different dates.

|

The original source did not identify the exact location or details for the diagram, but Stuart believes it represents a slice from the northernmost thumb of the field:

|

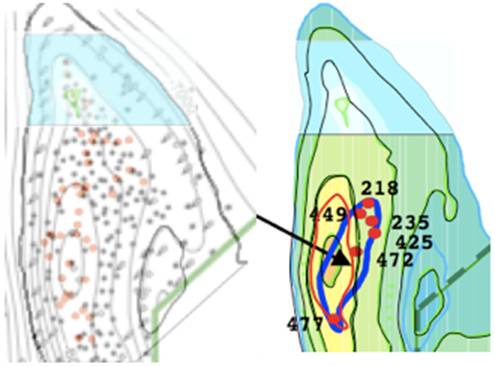

If that matching is accurate, it implies the following values for the oil water contacts over time:

| 1975 | -6550′ ± 50′ |

| 1979 | -6475′ ± 50′ |

| 1980 | -6450′ ± 50′ |

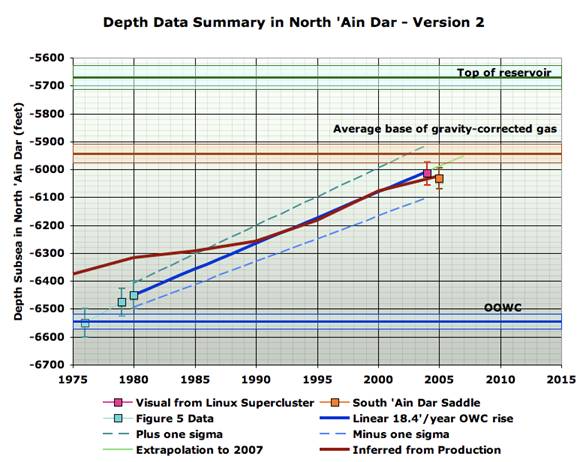

These three points are indicated by light blue rectangles on the figure below. Stuart combined the slope implied by these three points with that inferred from a number of other sources for this field to extrapolate the blue line in the figure below. The graph also includes a couple of more recent inferences (the fuchsia and orange rectangles) from public information that Saudi Aramco likely did not believe would reveal this sort of detail, but that Stuart, through careful sleuthing, believes he can infer.

|

By far the most important evidence Stuart brings to bear is based on an effort to reconcile various maps of the detailed geologic structure of Ghawar. With this and estimates of the permeability and porosity of the rock, one can then infer how a particular production rate (in thousands of barrels per day) would translate into a rise in the oil water contact over time. Stuart’s analysis appears to be quite detailed and sophisticated, including for example a modest planar slope to the oil water contact at a fixed point in time arising from differentials in water salinity. Stuart’s inferred path is shown in the red line above. Although one might quarrel about any single piece of evidence, the agreement of the inference from the various sources seems pretty compelling.

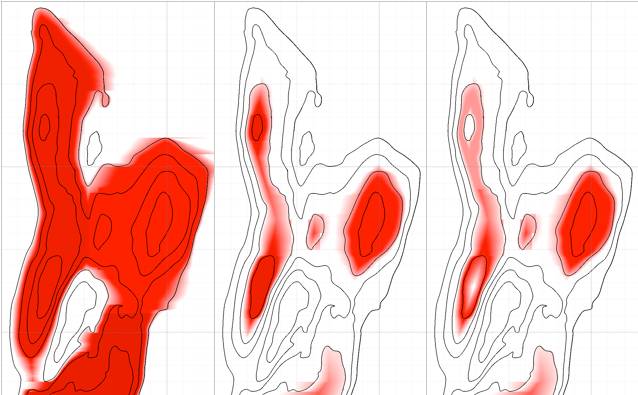

The following diagram shows the implication of Stuart’s computer-based simulation. The left panel displays the estimated extent of the oil before development, and the right panels show Stuart’s best guess of what is now left. The far right includes a separate modeling of the gas caps on top of the oil, whereas the middle does not.

|

If Stuart’s analysis is correct, it seems very likely that production from the northern part of Ghawar must have already entered a period of sharp and irreversible decline, which would account for the otherwise unexplained drops in Saudi Arabian oil production over the last two years.

To put this in perspective, the panels above represent only a small part of the 175-mile-long Ghawar oil field, specifically the section designated on the diagram below, in which red denotes oil and light blue the injected water:

|

Whether this picture describes a particular historical or simulated future condition is not known. In its original setting, the figure was intended simply to illustrate how Saudi Aramco’s detailed simulation model worked. But Stuart believes the figure accurately describes the condition of the field in 2004, and shows the same level of depletion in the north as implied by his own calculations; indeed, the inference Stuart draws from the above figure shows up as the fuchshia rectangle on the earlier graph of the slope (third graph shown here).

Now, one might conclude from this last picture that we’re only talking about depletion of a small part of the total Ghawar field. But based on the features of the rock, this is by far the best part, historically accounting for half the production from the field. Stuart acknowledges that

Southern Ghawar, by contrast, can maintain plateau for decades to come, but there is only 1.7mbpd of production there on last known figures.

Here I have only skimmed the surface of Stuart’s painstakingly detailed analysis. But let me briefly comment on what it means and why he did it. Neither Stuart nor I have a particular agenda here. The Saudis have been deliberately concealing the data that could settle this speculation quite conclusively. And yet, accurate information about what is ahead is absolutely vital in order to help us all make the adjustments and adaptations necessary for what is to come. Stuart observed that nobody had a compelling fix on the facts, even though the story may prove to be one of the most important events of our lifetime. For that reason, he decided that it was worthwhile for someone with his abilities to wade through all the detailed information available to try to form the most accurate picture of where things currently stand.

After Stuart’s monumental research, I really think the burden of proof is on those who claim that Saudi Arabian production can continue to increase. At this point, we need not the conclusions of experts nor the reassurances from Aramco, but hard data to support the claims.

If Saudi production is permanently on the way down, we have just entered a new phase of history.

Technorati Tags: oil,

oil prices,

Saudi Arabia,

peak oil,

Ghawar

Please pass ‘thanks’ to Stuart. And, thank you for continuing to shine the light on this, Professor.

Stuart Staniford has done a remarkable job in presenting the smoking gun in proving peak oil is here. The faster all of us realize this, the faster we can adjust to a less energy intensive society.

Good job Stuart, and thank you Professor Hamilton for being one of the few economists who actually “get it”.

Less energy intensive society will never happen. How are people going to even heat their homes without oil or natural gas? Electric heating.

Same for transportation- Rechargable electric cars.

All points to more nuclear power plants

With thousands of years of uranium supply scattered around the globe its inevitable

It’s often all very scary to read about peak oil, but can’t we make a judgement as to what price changes an x% change in supply would produce? Or is it simply the madness of crowds that determines this.

Interesting though – and am pleased to read an economist’s considered response to the questions

JDL,

Thanks for the information.

To put all of this into perspective:

In the 1940s Mid-east oil reserves were estimated at 16 billion bbls. In the 1960s that was revised to 250 billion. In the 1990s it was over 500 billion.

Known oil reserves have almost doubled since the 1980s.

The gloom-and-doomers concerning energy don’t have a very good track record.

Now this is not to say that Staniford’s information is unimportant, but it is much more important to Saudi Arabia than to the US. The world supply of energy is almost unlimited from coal to shale oil to uranium, hydrogen, and other sources many yet to be discovered.

This is what is so surprising and foolish about the secrecy of Saudi Arabia concerning their production. The dissemination of accurate information would allow the wisdom of the entire world to maximize Saudi profitability concern their oil. Once the Saudi’s run out of oil the rest of the world will simply pass them by.

all my oil engineer friends say that peak oil is a myth..

there is a boatload of oil down there..at a manageable extricability.

DickF said:

“The gloom-and-doomers concerning energy don’t have a very good track record.”

This is the kind of sound analysis we get from the cornucopians in response to Stuart. Does he realize that reserves are simply made up numbers in some of the most important cases? An essentialy faith-based response to a hard scientific analysis. I bet DickF is one of the ones who said we’d be back to $15 oil by now. And here we are at $65 oil and $3 gas. Seems like the doomers are racking up a pretty good track record now.

“The world supply of energy is almost unlimited from coal to shale oil to uranium, hydrogen, and other sources many yet to be discovered.”

This is an example of one of the most dangerous statements one can make. It lures people into inaction. It’s another faith-based platitude.

Please let’s not tolerate this kind of thinking anymore. There’s too much at stake. Let’s ignore these people and look at the facts.

You tell your engineer friends that anytime they feel froggy they can leap right in to the fight.

But analysis seems to be the great silencer of the Yergin Lynch rising production forever types. Like your oil engineer friends.

You know, it is lucky that belief is is unlimited, just like the amount of energy which many people imagine is just waiting to be used.

Unfortunately, the amount of oil is finite. Read the analysis of Saudi reserve estimation to get an idea of what finite means – unless you think that you can squeeze oil from a rock.

Don’t worry – though the Earth is finite, our beliefs are as infinite as our desires, which means we live in the best of all possible worlds.

It’s all good, to the last drop.

As a matter of fact, I have heard from reliable sources that the hurricanes of 2005 didn’t really happen – most people were deceived by the pictures on TV, which were only pictures after all, and it was all a vast conspiracy to manipulate prices.

See – no reason for concern, since reality is subjective.

Or something like that.

JDH –

Do you know of any good studies/reading on the elasticity of oil demand?

DickF said:

“The world supply of energy is almost unlimited from coal to shale oil to uranium, hydrogen, and other sources many yet to be discovered.”

There’s a lot of coal and shale oil, but the CO2 emissions from exploiting it would cook the planet

Hydrogen isn’t a primary source of energy, but a possible means of storing energy.

There is enough uranium in the oceans to last for thousands of years – but we’re a long way from having the infrastructure (generating capacity, electrified railways, ground source heat pumps) to rely on nuclear fission as primary energy source

sam said –

“all my oil engineer friends say that peak oil is a myth..

there is a boatload of oil down there..at a manageable extricability.”

A whole “boatload”?? Well, ok then. Phew. As long as it’s one o’ dem big boats dem preachers like Falwell have.

And it’s “down there”? Oh all right, we must be ok then. That’s all I need to hear. It’s down there! What’s the matter with you Peak Oil “thinkers”.

Lastly, I must admit, it truly made me laugh out loud to think that folks who use phrases like “…at a manageable extricability” would in the same statement use the phrase “all my oil engineer friends”. I mean really. All of them? What’s that, like 5-10? Oil engineer friends? I suspect only folks like Stuart and the Oil Drum folks have multiple “oil engineer” friends. I bet even JDH himself only has a couple oil engineers he counts as friends.

Such silliness.

Let’s get real.

This guy is an actual petroleum engineer who says that peak oil is bunk.

It’s a good read.

To Buzzcut, Leonardo Maugeri is an economist

who works for ENI (and not an engineer), to the

best of my knowledge.

j

Maugeri’s book is tripe.

Wow, it is really disheartening to see how few people can see that the world is currently organized around cheap energy, and that, if energy is going to get more expensive, it has ramifications in every realm of our lives.

This is not about doomerism, it’s about understanding that we need to think about our options and try to reduce the human suffering that will likely result from such an event, whether it be geopolitical or social.

He is an economist…

He never put a barrel in the tanks.

JDH and Stuart: This post, like others in the past, is the reason I’ve been visiting this site for maybe three years now. In particular, let the numbers speak. Investors, leaders, and policy makers must often make decisions before the numbers have spoken–placing their occupations partly into the realm of art and/or morality, the realm of values. I appreciate the focus here on what the data tells us, because that is exactly what we should expect of science, whether that of JDH’s economic science or Stuart’s grappling with geological science.

Great work.

BuzzCut and DickF: I do not believe anyone knows what the implications are for the world reaching maximum oil production. Alternatives, including coal, are capital intensive and not as energy rich. There is no data that I’ve come across–and at this time I have a library of maybe fifty books on the topic–that makes me think the peaking of world oil production will be a non-issue, with a simple transition to whatever lies beyond. My gut told me–based upon reading information here and elsewhere–that energy was cheap in 2003, and I invested accordingly. My gut also tells me, based upon reading this topic for maybe five years, that the response to peaking energy production will be difficult, maybe very difficult.

It is good that an economist with as much experience as JDH jump into this issue, but we see already in the comment so many people referring to hearsay and anecdotes rather than to science or reason. It reminds me of the professor’s posting last week about the survey that showed a not inconsiderable percentage of Democrats believed Bush knew about the impending 9/11 events before they actually took place.

What Stuart has done is hard work and he has accomplished, with as much circumstantial evidence and older measurements that he could find, to pin down the question of whether KSA’s #1 resource, the world’s largest oilfield, is now depleted so far that significant declines are ahead and increased production is out of the question.

There is only one kind of rebuttal by which such a study can be shown definitely wrong – hard physical measurements of physical object. The only source for that is ARAMCO and the fact that they refuse to tell ought to be a red flag for everybody, but especially US citizens and politicians who are worried about our future.

This is what is so surprising and foolish about the secrecy of Saudi Arabia concerning their production. The dissemination of accurate information would allow the wisdom of the entire world to maximize Saudi profitability concern their oil. Once the Saudi’s run out of oil the rest of the world will simply pass them by.

Dick brings up an interesting point. Why aren’t the Saudis more forthcoming on the situation? You would think that news of an impending shortage would increase the price of oil and their revenues.

I can think of a few reasons for them to conceal their status. First is that they learned during the 70’s oil shocks that the market can respond pretty quickly and drive down the demand for oil. Second, the news could lead to a worldwide recession and lower demand. Most importantly, the Saudi government is precariously propped up by social welfare and bribes to religious extremists. The royalty might not last very long if it were known that the golden goose is on life support.

We domesticated horses for work. We found ways to use the wheel to improve transportation. We harnessed steam, created railroads and steamboats. We found a use for oil in only a little over 100 years ago and we have tamed the power of the sun to generate energy.

No one knows what tomorrow will bring. Batteries are improving to store the energy of the sun and nano-technology is making our existing sources of energy amazingly more efficient.

What surprises me is that those who wring their hands the most about running out of oil are the ones who yell the loudest about alternative fuels. If you force conservation and a restriction on energy sources you are actually fighting against alternative fuels and energy sources. Free up the oil and let it flow. Allow companies to exploit their products to maximum efficiency. This is when you will see energy alternatives.

I am not opposed to Staniford. Just the opposite. We need to free scientists like Staniford and let them lead the way. You can be doom and gloom and call on the government to stick our heads in the peak oil, or you can be part of the solution and support companies who are promoting energy production. One leads to hardship while the other leads to continued prosperity.

“In the 1940s Mid-east oil reserves were estimated at 16 billion bbls. In the 1960s that was revised to 250 billion. In the 1990s it was over 500 billion.

Known oil reserves have almost doubled since the 1980s.”

I just want to make the point that reserves are only tangentally related with Peak Oil. PO is all about production, not reserves.

Anetta, a nice review of the literature is provided by Jonathan Hughes,

Christopher R. Knittel, and Dan Sperling in Evidence of a Shift in the Short-Run Price Elasticity of Gasoline Demand. They note that historical estimates put the price-elasticity of demand (the absolute value of the percent change in quantity demanded divided by the percent change in price) between 1/5 and 1/3. However, if you look just at the most recent data, you get numbers like 1/20. I had a quick summary here of how you can justify the 1/3 number. A new paper by Paul Edelstein and Lutz Kilian (that I’ll be discussing in a separate post later this week, by the way) also comes up with 1/3. I also recommend Timothy Considine’s paper in the Energy Journal, Is the Strategic Petroleum Reserve our ace in the hole?, which comes up with a number around 1/6 (ignoring inventory adjustments).

One point I take away from the Hughes-Knittel-Sperling analysis is that the price-elasticity of demand is probably not a constant, but varies with the level of income– the higher the expenditure share on energy, the higher I would expect the elasticity to become. It also depends on the perceived permanence of the price change.

Even so, I have to admit to having been surprised that, apart from the autumn of 2005, we so far haven’t seen much of a response of U.S. gasoline consumption to the price increases over the last four years.

Professor Hamilton-

The key question is: how does an intelligent layman evaluate claims which are based on specialized knowledge/analysis?

The Oil Drum’s mission statement says “This real and tangible crisis of supply and demand is now inevitable. Whether the coming crisis arrives in six months or in four years, whether the crisis arrives in a slow, secular fashion or as a cataclysmic “shock,” our purpose is the same: we are here to raise awareness of the reality of the current problem and to attempt to address the real issues that are often hidden by political pandering.” They may be right, but I suspect that the principals behind the OD are not wholly objective.

Has someone with knowledge checked Mr. Sandiford’s work or independently reached a similar conclusion? I know from my own professional experience that detailed analysis can be fundamentally wrong if one or more assumptions are incorrect. Further, if Mr. Sandiford is correct, I would expect other observers with large financial interests to have researched the issue and come to some conclusions that could be compared to his results. Can he point us to some other studies agreeing with his conclusion?

Like DickF, I am skeptical based on the track record of past predictions (e.g., Club of Rome, Paul Ehrlich) and my understanding of the workings of the price system. If oil production is to decline, I would expect that prices would rise in anticipation, and the search for alternatives and new supplies to heat up. The reserves of oil are obviously finite in the very long run, but in the medium run are highly dependent on prices and technology.

DickF wrote: “No one knows what tomorrow will bring.”

Exactly. That’s why I strongly argue that people should not assume that past results are indicative of future performance, that analogical thinking–about horses, wood, whale oil, coal–is not necesssarily pertinent or appropriate to what we will find when oil production peaks.

We don’t know. And I wish the cornucopians and the doom and gloomers would stop pretending they do. Let’s focus on facts. Markets have multiple ways to deal with shortages. Demand destruction, or alternatives. Demand destruction includes recession and depression.

The facts don’t tell us what we’re facing, and I’ve love it if people would stop pretending that they know the future, including the author of the above quote.

I would think that oil over $60/bbl and gas of $3/gallon is the appropriate response to peak oil. Whether peak oil is a fact this year of in 20 years or in 50 years, current pricing would appear to be sufficient to make alternatives attractive.

I think that the skeptics argument is that oil pricing has crashed often enough that there is another price crash siometime in the not too distance future.

In terms of production, large portions of the world’s oil reserves are undercapitalized for a variety of geopolitical reasons.

JDH –

Thank you very much for that great info and for those links. I look foward to reading them.

Rich Berger –

You’re right. But Stuart’s data, his methods, his presumptions are all there for anyone to take apart. I’m sure he would welcome your or your experts’ challenges on these grounds.

What makes his analysis extraordinary is that to date, no one has done such careful, rigrous science on this field and published it for free for all the world to challenge.

If we agree oil supplies are important to the world, faith-based assumptions, positive or negative, get us nowhere, and work like Stuart’s could very well be what saves civilization from grave mistakes.

Let’s hope experts who do rigorous scientific analysis come out and prove Stuart wrong. I think we’d all like that.

I would note that although you’re right, the Oil Drum is full of peak oilers to be sure, it is also full of the most skepticism, rigorous analysis and criticism to be found on this subject. If you put up phony science there, you’ll be shot down in minutes by any of dozens of oil industry veterans, geologists, physicists, statisticians, and others, who put up their work for open critique.

Such careful expert thought and open debate is why I believe the Oil Drum is our most precious “think tank” when it comes to the future of oil.

Rich Berger wrote: “I am skeptical based on the track record of past predictions (e.g., Club of Rome, Paul Ehrlich)”

I agree that we should be cautious about the failure of past predictive efforts. But I add that we should look at the merit, depth, or soundness of those predictions–and compare them to the validity of more recent predictions. Science progresses, including the science of prediction. A back of the envelop Ehrlich prediction is not comparable to the work of Staniford or JDH. The same science that individuals point to as the path forward for energy–alternatives or whatever it may be–is also the science that makes predictions. We can’t have it both ways, picking and choosing the science that fits our needs–science will forge a forward path–while ignoring the science that tells us of the current state and the pros–and cons–of the path forward.

If I’m not mistaken, the Club or Rome did not intend to make specific predictions, and if they did, they were wrong. I believe they primarily raised the issue of limits, which I think is a sound issue to raise. The bet that Ehrlich made was just plain dumb, as silly as the one that Matthew Simmons made a while back–and his prediction of gas prices at the end of 2006, which never came true. But these bets should not detract from sound analysis. As I look at issues like this, there are people I tend to ignore, or at least discount. I’ve discounted Matthew Simmons for a while, e.g. that bet bugged me. So he gets a big discount.

I have no discounts, by the way, on Stuart or JDH. Both come highly rated from my perspective. Top notch.

And I agree with Rich’s comment that the analysis should be appropriately peer reviewed. I think the Oil Drum tries to bring multiple perspectives to the issue of energy–showing multiple sides, one might say balanced–without too much extremist meandering. For that, I commend them. I abandoned peakoil.com years ago because I couldn’t stand to be associated even a smidgeon with a place that included what I considered to be unsavory characters. I switched to the oil drum and econbrowser and haven’t looked back. They do the dirty work of sorting through the conspiracy and end-of-the-world hand-wringing that infects other peak oil sites.

R Berger,

How do you define medium term? We’ve been pumping oil since the late 1800’s. The long climb higher is just that, longer than the slide down. Everyone keeps talking about all this shale and tar sands without even considering the methods to secure the oil. Alberta claims they will never produce more than 3mbpd. Shale has to this day, produced how many barrels? Oh and how do they even make oil from shale and tar? Oh they heat it with natural gas, but gee isn’t that another hydrocarbon energy that is going to end? Yep.

Stop picking at the skin and cut it already! Read a little more on the system you don’t see. You’re right TOD isn’t objective, it’s right. You agreed that oil is finite, and so do they. I’ve been over there for about two years and I dare you to put your feet into the water and defend your ideas. They will be torn apart and not because you’re new, but you don’t have the daya to back it up. Have you even spent time on the site? Do you you read the highly technical reports they put out day after day. Not to mention the economists/engineers in general who can provide an insight like none other.

Think about it. Energy is the basis for everything. When the cheap energy is gone, it won’t matter about alternatives as NOTHING comes close and you don’t get that. Break down a barrel of oil into raw BTU’s. Now compare a barrel of equivalent coal, ethanol(what a JOKE), or anything else you feel free. NOTHING EVEN COMES CLOSE!!!! Nuclear is the only option for your homes and business’, so we all need to get used to it if we want to MAINTAIN our standards of living.

As for your problem with indepedent anaylsis by others in the field, good luck. YOu’ve got to get some basic facts of life and that’s people do things for selfish reasons and you and I are included. The automotive industry has a reason to down play PO, especially since they sell guzzlers to ssruvive. USE some common econmic sense. It’s about incentives! The advertising/media industry has an incentive to sell ads on tv which (if you watch any, since I Know many of us don’t) advertises the hell out of cars in general. The finance companies are making fat cash financing vehicles so why would they want to push peak oil?

You’ve got to understand the large interests that are GOING to lose when we power down. I’m not all doom, I’ve got a small part reserved for batteries. IF battery technology advances enough, and we can store energy without losses or minimal over long periods of time, then the issues might be a bit overblown. However I’m not prepared to plan my entire future based on a battery.

Rich Berger, I’ll lead the charge when it comes to criticizing the methodology of the Club of Rome. You also make an excellent point about wanting to see outside confirmation. I think Oil Drum has made an effort to cultivate discussion, as for example this piece from Jeremy Gilbert. Their comment sections (and ours of course) are open to anyone. In the lengthy reactions to Stuart’s piece over at the Oil Drum, you’ll see all sorts of technical discussion of the details, but I didn’t notice anything from anybody that I’d summarize as concluding “this is just plain wrong.” I think the responsible opponents to Stuart’s claims would take the position, “we really don’t know for sure”.

And, I agree, we don’t. Perhaps that’s part of the answer to your question of, “why isn’t this in the price?” That question has certainly also been forefront in my thoughts all along here. But Stuart’s efforts have moved me in the direction of thinking it’s more likely to be one way rather than the other, and that the market may not be calling it correctly here– his analysis, after all, is something new. That’s not a position I’m usually very comfortable with, but I do the best to try to juggle what I know into a coherent synthesis of reality.

In any case, as long as the debate is focused on questions such as “what is the present height of the oil water contact in North ‘Ain Dar”, I think we have hopes of making progress, and should encourage intelligent people to examine the evidence together in good faith. And I believe that is exactly what Stuart has tried to do.

What many economists fail to realize – and Prof. Hamilton is a welcome exception – is that natural resources aren’t like widgets. More sophisticated production techniques don’t necessarily lead to lower production costs. Eventually they’re merely an exercise in running faster just to stay in place, because the easiest (read: cheapest) oil was extracted first.

For instance, discoveries such as 2006’s much-publicized Jack 2 – at a depth of 28,000 feet, including 7,000 feet of water, in a hurricane-prone environment – may increase reserves, but they won’t do anything to lower the cost of oil. At $40 a barrel, Jack 2 simply ceases to exist as a meaningful reserve, because there’s no way to produce it profitably at that price. (Nor do I find any news that Chevron has plans to develop the field, even with prices reliably above $60.)

And that’s why phrases such as “manageable extricability” are meaningless. There are many uses for which oil will still be a bargain at $100 a barrel. But many current uses will no longer be economical at that price.

“What surprises me is that those who wring their hands the most about running out of oil are the ones who yell the loudest about alternative fuels. If you force conservation and a restriction on energy sources you are actually fighting against alternative fuels and energy sources.”

We’re continuing (and in some cases accelerating) a government-subsidized push to sprawl all over our continent in ways that will be completely unsustainable once oil gets a bit more expensive. At a bare minimum, this needs to stop and be reversed – and, no, hydrogen can’t save the suburbs.

“I would think that oil over $60/bbl and gas of $3/gallon is the appropriate response to peak oil.”

We don’t even pay for all direct roadway spending from gasoline taxes today, much less mitigate carbon emissions, so, no, $3/gallon gasoline isn’t enough. Especially when combined with tax and regulatory policy which essentially forces suburban sprawl at the expense of urban taxpayers.

M1EK-

I don’t know what state you live in, but here in NJ, the taxes collected from motorists exceed the expenditures on roads and other items required for cars and trucks. On the other hand, our state mass transit agency, NJTransit, meets about 40% of its cost through fares. I found this out during a pre-blog era debate in the letters to the editor page of my local newspaper, the Bergen Record.

Yes, Leonardo Maugeri is an economist, not an engineer. That’s probably why his book was such a good read! Anyway, my bad.

What I took away from “The Age of Oil” is that these “oil crisis” come along every once in a while, and each boom creates the conditions for the next bust. The energy crisis in the ’70s set up the glut of oil that resulted in 89 cent a gallon gas in 1998 after the Asian financial crisis.

Another interesting take away was that the whole reason for Rockefeller creating Standard Oil was to try and rein in the boom/ bust cycle in the oil industry. The Seven Sisters performed the same function on world oil markets after WWII.

None of this is to say that peak oil is absolutely wrong, just that we should be cognizant of past history in this industry.

Also, who here believes that the $3.50 a gallon that I just paid this afternoon for gas is a result of the cost of a barrel of oil? Bigger isses are refinery capacity, maintenance, summer blends, etc.

Based on past experience, at $68 bucks a barrel, gas should not cost $3.50 a gallon in the Chicago suburbs. But here we are.

This industry has countless issue besides peak oil. Downstream operations are an absolute mess. I have no hard data to prove it, but my instincts tell me that the switch to ultra low sulfur diesel has something to do with the current high prices as well.

In the past, geologists and petroleum engineers have said equally silly things to me such as there is plenty of oil. Well, if there is, where is it? World discoveries peaked in the early 1960s at massively higher levels than current discoveries. Discoveries for a few decades have been very very small (less than annual usage). You can’t do that forever with a physical product like oil. You might with a non-entity like dollars but not with real matter and energy.

So we are left with a question to all these cornucopian geologists and petroleum engineers – if there is so much oil, why aren’t you finding it? If there is so much oil, this must mean that you people are either (a) incompetent or (b) lazy.

Or maybe there is not so much oil after all.

Especially when combined with tax and regulatory policy which essentially forces suburban sprawl at the expense of urban taxpayers.

Just curious as to what policies you think cause sprawl. Tax deductibility of mortgages and property taxes (and now PMI!!!)? Low gas taxes?

Myself, a house in the suburbs is the American Dream, and even if you punatively taxed suburbs and subsidized cities, all you would do is shift peoples’ preferences at the margin. You would not stop suburbanization or sprawl to any great effect.

We don’t even pay for all direct roadway spending from gasoline taxes today, much less mitigate carbon emissions, so, no, $3/gallon gasoline isn’t enough.

Doesn’t Al Gore say that a carbon tax equivalent to $1 per gallon would be enough to mitigate global warming? Maybe that’s the low end of the distribution?

“I don’t know what state you live in, but here in NJ, the taxes collected from motorists exceed the expenditures on roads and other items required for cars and trucks.”

That is almost never the case. You are likely ignoring the property and sales tax contributions to roadway funding. (I’m not very familiar with New Jersey, but in every instance with which I was familiar, including Pennsylvania, people have tried to make similar claims of self-sufficiency that were easily debunked).

Be sure you include the entire major roadway system – not just roads with a route shield on them. Anything your MPO would call at least a collector, for instance, serves interests more than direct property access and should therefore be funded by gasoline taxes over property/sales taxes.

Here in Europe we pay about $6/gallon and we don’t cry.

Sooner than later, USA prices will go up too, and a big tax increase on gas would be a healthy start, though not very popular.

JDH wrote: ” The Saudis have been deliberately concealing the data that could settle this speculation quite conclusively.”

Couple thoughts/questions:

1. Are there any other countries, e.g. other Middle Eastern producers, that are as secretive with data?

2. Public companies are required to state reserves. I assume private companies can do whatever they want. Unless those they supply demand data. Which implies, I suppose, that Saudi Arabia can do whatever they want, to the degree that the analogy holds between a private company and an independent country with rights over its territory. As a customer of oil, and the largest consumer of oil in the world, even if not directly Saudi oil, the US can demand data–but that doesn’t mean we’re going to get it. What can we do about it? Not much.

On the speculative side, what are the possibilities regarding Saudi (a) awareness of future production and (b) political handling of production data?

1. Could the Saudis, at all levels, be ignorant of the state of their fields? This seems unlikely. I say no.

2. Could the Saudis, similar perhaps to Enron, have pockets of accurate knowledge about the state of affairs, but no centralized acceptance of reality? Has ideology and corruption and wishful thinking infected the kingdom? Quite possibly. They could be collectively deluding themselves.

3. Are the Saudis hiding data for nefarious reasons? What would these nefarious reasons be?

4. Could the Saudis be trying, through subterfuge, to allow uncertainty to incrementally increase the price of oil, to try, as best as possible, to avoid shocks to the system, in particular shocks due to panic in the markets? I think this could be as well. Perhaps even in collusion with the US government? Possibly.

Here’s a question I have. I’m all for openness and data transparency. But my question is (one I raised long ago): What data do we want from them? And what would we do with it? In particular, how would that information percolate through the economic and political systems? It is all pro? Are there any cons to certainty? I realize this is a questionable argument I’m making: ignorance is bliss. But there was a discussion, years ago on peakoil.com, in which many argued that the US should military force the Saudis to cough up the data. I always argued (a) military adventures would probably result in increased difficulty producing oil irrespective of how much is in the ground, e.g. Iraq and (b) what would change in our system once we had the data?

Is certainty in business and real-world enterprises always best? For everyone? Or are there times when uncertainty smoothes out transitions? And I’m not playing devils advocate on this. I don’t seriously know the answer.

M1EK-

Not in NJ. The bulk of property taxes go to pay for our inefficient government schools (I estimate 70%). The remainder go to local governments, a small part of which could potentially go to local roads. Sales taxes go to the state government. Simple fact – expenditures for roads are exceeded by revenues from motorists.

Given that with regard to the section of the field analyzed above “we’re only talking about depletion of a small part of the total Ghawar field. But based on the features of the rock, this is by far the best part, historically accounting for half the production from the field”, I would find it interesting to know how much effort the Saudis have put into exploring the rest of the field. Since oil prices were extremely low between the early 1980’s through the late 1990’s and this one small section was producing so well, I doubt that much exploration has been done. The financial incentive hasn’t been there.

My thanks to JDH for linking to my analysis of this question, and a couple of observations.

Firstly, to second what others have said: I welcome critique by any and all knowledgeable professionals. Nothing would please me better than the best technical people studying the available evidence in detail to see if it indeed means what I believe it means, or better still, if more meaning can be wrung from it.

I should stress that blanket “there isn’t enough data” or “oil prices always came down before” type arguments are much less useful, however, than specific “you ignored/underestimated XYZ in your table of uncertainties, so the error bars are really ABC bigger than you think” type arguments.

Also to thefinancedude. I have historically been pretty optimistic about the plug-in hybrid story. However, The Trouble with Lithium raises cause for concern about the scalability of that answer – though other battery technologies may yet make it the path of choice.

Finally, on the questions about Ehrlich and the Club of Rome. Ehrlich clearly exercised poor judgement and overstated the case. However, the “Limits to Growth” study funded by the Club of Rome was a good deal more cautious. Even in the first edition of the book (which they updated twice more each decade or so), they saw the main crunch coming in the early to mid twenty-first century. I don’t think I’d say that was proven wrong yet, and certainly we do seem to be running into more and more “full world” type issues. There are details in the first book that aren’t right, but they never claimed their model was anything more than a rough approximation – and, to the degree of precision they claimed, it’s not clear they were wrong. Our task as a civilization is to prove them wrong, I think (something they urged us to do!)

re: Transparency

I had lunch with Stuart a few months ago. He’s very bit as intelligent and personable as one would imagine from his writings.

He asked my help in arranging a corporate-level symposium on peak oil. I declined knowing full well what my management would say – no. Yet I’m certain the “big boys” harbor no illusions as to peak oil.

The reason very large corporations and governments like KSA do not want to reveal energy predictions and their strategies in dealing with the various scenarios is because knowledge is power. The real world is very much a competitive scramble and always will be – showing your hand is a weakness and weakness is never a virtue.

Re: Nuclear power

Even when peak oil is an obviousity, I will not argue for lynching all the anti-nuclear activists who have prevented the prior construction of new nuclear plants. We will have missed a great chance to build the infrastructure needed post-peak. Likewise for the California Sierra Club who have blocked the construction of an electrified high speed rail connection between SF and LA.

Mock them, ridicule them, scorn them – just don’t hurt the poor misguided fools.

Note to M1EK re our past exchanges about STP:

Earlier had no connection with STP but now – I’m building units 3 and 4!!!! Great team there, BTW. Too bad the City of Austin declined participation in the new units. They will just have to buy on the spot market at a handsome profit for the owners of the new units.

M1EK and Rich Berger…

I have to agree with Rich’s estimate. It would be the same in Massachusetts save one debacle of a road project.

Where road expenditures exceed vehicle related taxes and fees , I would argue the efficiency on the spending side.

I argue that the urban model is more important to the waning manufacturing economy than it is to the growing service economy.

Rich,

That doesn’t address the common problem: state sales tax, state property tax, state income tax, local property tax, local sales tax, local income tax being used to build/maintain non-trivial roads. Could be local sales taxes passed for transportation (common in growing suburban areas) which are just added to the fuel tax pot. Could be localities maintaining arterials and collectors – and not getting corresponding trickle-down gas tax money. Could be the state paying for the highway patrol directly rather than through fuel taxes. Etc.

It would be very, very, very unlikely that road spending in NJ doesn’t exceed fuel tax collections when you count ALL direct road spending (new construction, maintenance, highway patrol, etc). Your fuel tax isn’t much higher than the norm, and your higher operating costs certainly more than make up for the lack of new roads. This doesn’t count indirect costs like pollution, of course.

Again, arguing from generalities rather than data – I’d cheerfully look at anything you have – but in every other instance, data has always led to the same conclusion for other states in which people were just as certain as you were. Most aren’t as massively subsidizing roads as is Texas, but neither is fuel tax the cash cow your average suburbanite believes.

JS, even the most red-meat conservatives in the area wouldn’t touch the STNP with a ten-foot pole after the money the city lost the first time around. If nuclear is the slam-dunk you claim, you don’t need to sugarcoat it like that.

One (very old) report that I found at the top of google:

http://www.tstc.org/bulletin/19950414/mtr03001.htm

concludes a subsidy of about 3/4 billion dollars in New Jersey in 1995.

Note that they even include vehicle registration as a user fee in their figure before concluding a large subsidy – we weren’t even including vehicle registration (which I believe to be unfairly used to fund roads as it penalizes rare drivers in favor of frequent ones). They also include parking fees and the like – which are a subsidy but, again, not part of the fuel tax you asserted more than covers the cost of road spending in NJ.

I have commented before on the reasons for Saudi secrecy. They are both domestic and international, diplomatic and strategic. Furthermore, it is a society that is a monarchy run by a tight family group. They are simply very secretive out of habit.

There would seem to be two big questions. The first one is al Ghawar, much discussed here already. The other is the status of reserves in the Empty Quarter, al Rubh al Khali. Those have also been matters of great secrecy. So far there has been little production out of there, but it is the harshest desert on the planet, not crossed by a European until 1917 (Harry St. John Philby, adviser to Abdulaziz and dad of the Soviet spy, Kim Philby). Costs are certainly much higher to produce there than elsewhere, even if there is a lot of oil there.

The straw in the wind is that they are clearly ramping up efforts to produce out there, with the new contract with the Russians to build pipelines from there to the Gulf facilities at al Abqaiq.

Mr. Rosser,

There might be something to your Empty Quarter hypothesis.

When I scroll around that area on Google Map there sure seems to be a lot of industrial activity for an “Empty Quarter.”

I don’t have a baseline so can be definite as to any uptick but something’s going on.

M1Ek,

So the city LOST money. Sounds like a failure of socialism to me.

To Buzzcut,

None of this is to say that peak oil is absolutely wrong, just that we should be cognizant of past history in this industry.

Peak Oil is a fact and absolutely certain, I’m afraid. You can look at U.S. production figures.

Despite all ingenuity and technology U.S. production is in terminal decline.

World peak oil timing is debatable, not the very concept of PO.

Stuart, JDH: Nice work.

A couple of things worth remembering on forecasts, steadily increasing reserve estimates and shale oil.

1. Back in the late 1950s/early 1960s, Dr. Hubbert did a pretty good job of predicting that US oil production in the lower 48 would peak around 1972. Even throwing in the North Slope production in the mid-to-late-1970s didn’t change the outcome much – it just generated a lower second production peak out in the late 1970s. If Hubbert’s theory did a decent job of forecasting US peak production on or about 1972, then I think it’s got a very good shot of working on a global basis in the 2007-2010 timeframe.

2. IF you look at the IEA data for the past few years you get this: 2003 global production 79.8 mbl/day and avg price $30.98, 2004 global production 83.2 mbl/day and avg price $41.31, 2005 global production 84.5 mbl/day and avg price $56.83 and 2006 global production 85.3 mbl/day and avg price $66.63. As a professional analyst, I have to ask: why wasn’t there a greater supply response to higher crude prices? Now maybe, just maybe the increase in price was dampening DEMAND and the supply of oil could have been much greater in response to the higher prices if there had been native demand (or cheap above ground storage) for it – but let’s look at North American production then . . . . .

3. Because no matter what else you think about this near-circular supply/demand issue, given the importance of reducing American reliance on imported oil, North America should be investing extra dollars and producing flat out, right? So in 2003 N.American oil production was 14.6 mbl/day with avg price of $30.98, in 2004 production was 14.6 mbl/day with avg price of $41.31, in 2005 N.American production was 14.3 mbl/day with avg price of $56.83 and in 2006 N.American production was 14.3 mbl/day with avg price of $66.63. As a believer in the weak form of peak oil, frankly, I’m surprised that N.American production has been flattish even as the price of crude has risen by 115% — but skeptics of peak oil such as Mr. Yergin should be held to account: 3D seismic, 4D seismic, oil sands and enhanced recovery techniques have NOT grown N.American oil production even as a doubling in oil prices has incentivized much higher production capital spending efforts.

4. For about 9 months in 1981 I worked on the Exxon/TOSCO Colony Shale Oil project. There was nothing easy then about getting the gooey stuff out of the rocks on an economic basis and after investing several billion dollars Exxon gave up. The in situ processes hold promise but are still going to be hard to scale, just as the oil sands in Canada are proving difficult to scale because of the remote location, harsh weather and other issues. The hard reality is that there’s a reason why the lower 48 is drilled out while not much has been done with oil sands, shale and deep-deep water drilling: it’s HARD to produce product at economic prices in remote locations or with bad rocks, and if it wasn’t HARD it WOULD HAVE BEEN DONE ALREADY.

5. In my day job I regularly meet with the executives of energy production and energy drilling/service companies. I usually ask whether they think Hubbert was a genius or a crackpot, and they usually answer “CRACKPOT”, though when pressed on specifics they’re usually not that impressive. For those of us with long memories it’s interesting though: in 1981 Exxon was forecasting that the price of oil was going over $100 by 1986 and instead it went to $10, and today Exxon is forecasting that the world will be producing 130 million barrels per day in a decade or two and I’m betting we never get close to 100 mbl/day ever – in fact I doubt that we’ll get over 90 mbl/day, but we’ll see.

Well, enough for now.

I pray that the Family Sa’ud is running out of oil. They have used the money they have gained by selling oil to spread the a reactionary totalitarian version of their religion and finance terrorism. When they go back to being desert banditos like their accursed ancestors the whole world will be a better place.

The rest of us will get by without the Sa’uds. We have the resources and the minds to use them.

My question is, where is academia on this? Academics have been in the lead on the global warming issue, pushing for many years to keep it on the agenda, emphasizing that this is what the science predicts and tirelessly debunking the many naysayers.

Don’t we have some academic field where the question of near-term Peak Oil would be within the purview of experts? Resource economics? Petroleum engineering? Plain old geology?

Climate change is getting enormous attention even though the most serious consequences are the better part of a century away. If the more apocalyptic Peak Oilers are correct we face a crisis in our civilization within a decade. Some predict that a large fraction of the human race will be killed as our oil-dependent global trading networks collapse. Compared to this threat, climate change is a trifle.

We as a society look to academia for factual, unbiased information on the natural and human worlds. Oil production levels are certainly an area where academics would be expected to study and acquire expertise. If Ghawar oil field, the biggest in the world, is really facing an inevitable production decline along with Cantarell and all the other super-giants, we are likely going to be dealing with a true global Peak Oil crisis within a couple of years if not sooner. Why have we heard nothing about this from mainstream geologists, economists, and other specialists?

This could be the biggest failure to prepare for a foreseeable crisis in history. And much of the blame should fall on our academic researchers for letting this problem creep up on us without warning or time for preparation. I can’t understand how and why the climate change issue has been handled so differently from Peak Oil. I still am inclined to conclude that all this doomsaying is a bunch of nonsense and in fact climate change really is a much more serious problem than PO.

Prof. Hamilton,

Thank you for posting an adaptation of Stuart’s work for dummies. I never have enough time to read through his thorough and vast analysis on the OilDrum. Please don’t stop with this work – Stuart usually produces an article once in two months or so, and most of your readers would love to read more

Are there any other countries, e.g. other Middle Eastern producers, that are as secretive with data?

Yes, just about every other nationalized oil producer, excepting probably Norway, is quite secretive.

They all seem to share similar interests in keeping quiet—mostly relating to competitive positioning versus rivals and internal domestic politics. Russia is now clearly effectively re-nationalizing its oil and gas into opaque pseudocorporations—government sponsored agencies? The oil equivalent of Fannie Mae?

Somebody in the industry posted on the Oil Drum that he believed that Saudi Aramco was in fact more open than its OPEC peers, which could well be true. And yet, still it is obviously far more important.

I have little doubt that the Saudi’s primary motivation for keeping things secret is to keep their heads connected to their necks, literally.

If word got out that they were in irreversible terminal decline—and this means the point at which oil production decline outruns price increases—the anger at the royals for dissipating the national treasure would be potent gasoline for a fundamentalist revolution and universal royal beheadings.

The fanatic mujudaheen of the Islamic Caliphate of Arabia would certainly fly through Riyadh, and quickly overthrow the rest of the oil-producing Gulf statelets as well.

Peak oil is not bunk. It is common accepted knowledge. There is disagreement on the timing of it. I am an oilfield engineer and happy to report that virtually everybody I know accepts peak oil. We argue over the when, not if.

What people do not realize is that the ptoblem with peak oil is not running out of oil overnight but it is mostly a supply issue. There is plenty of oil shale, oil sand and coal. Yet getting it out takes time and loads of people and money. You can’t just drill a hole and energy flows out…

Further more the reserves of oil are most likely lower than the official estimates. The reserves of coal are not nearly as great as people like to believe. A lot of it is poor quality and difficult to extract.

A far bigger worry is the impending drop in natural gas production, which usually follows a decline in oil.

Consider the following reaction: N2 + 3H2 yields 2 NH3. 90% of the worlds ammonia production comes from this reaction, with the hydrogen source being methane or CH3

Now track the hydrogen atoms in the world’s food supply. They go from natural gas into just about everything plant that is fertilized with them, then we eat them.

Indirectly the world’s population is consuming natural gas, and it is headed for terminal decline. Less methane = less human beings on the planet any way you cut it.

Professor Hamilton writes

My position is “we really don’t know for sure”, but I am not an opponent of Stuart. The real point is in the post —

Will Stuart’s efforts pressure the Saudi’s to reveal what’s going on? Sadly, the answer is “No”.

Where do we stand? The EIA/IEA says Saudi Arabia has spare capacity in the 1.5 – 2.5 million b/d range. Stuart says they have very little, effectively zero, if he is correct. Some people will choose to believe Stuart, most will assume that “business as usual” continues as far as the Saudis are concerned. If Stuart is wrong — and events could easily falsify his hypothesis — then it might be hard to say what has been accomplished at The Oil Drum. On the other hand, the arguments made there leave little doubt that if North Ghawar is not in steep decline now, it certainly will be by 2014 at the outside, a mere seven years from now. And, that is probably far too generous an estimate. So, everybody should be planning for this eventuality anyway. The real point is that Saudi Arabia will never produce the kind of numbers that future projections from the EIA/IEA require.

I would remind everyone at this point that Iraq, which is potentially a prolific producer in the 4+ million b/d range, is effectively offstream except for about 1.6 million b/d in the South (Basra, Rumaila complex). Obviously Saddam Hussein was a problem, but now we have no one to blame but ourselves. Events in Iraq have been almost completely predictable since the “Shock & Awe”. Oil Mission Accomplished, indeed! I point this out because there is a strange imbalance in which people obsess about Saudi Arabia, and ignore Iraq.

These remarks represent my personal views, not those of ASPO-USA.

Dave

A possible reason production in S.Arabia is declining is due to them trying to overproduce while the barrel price was high.

There is a property of oilfields that they have a sort of “natural” recovery rate. You can exceed that, but the more you exceed it, the lower the total useful yield will be. Pumping water in doesn’t create a nice ocean of water with a nice ocean of oil floating on it; it creates an ocean of oil/water mix with oil floating on it, tying up considerable amounts of the oil in a form from which it cannot be easily recovered. Increasing the force with which you pump the water down increases your recovery rate at the cost of the increased turbulence losing you more of the total oil.

Saudi Arabia has (probably) been trying to pull more oil, to make more money, without drilling more holes, which cost money.

That’s the downside of high, but volatile oil, prices.

Oh, my God!! We’ll have to start getting oil from all the unused wells in Alaska, and Africa and Russia! The horror!!!

Purdue University just made hydrogen on demand. So this is good timing. 😉 L

I usually like to boast about my tendencies to heterodoxy in economics, but on this issue, the conventional mainstream is correct. The market will work. If and or when we hit peak oil and global production goes down for good, not just in the mega fields of al Ghawar and Cantarell, the price will really go up and we will see people adjust, even if it takes time. The SUVs on the US highways will gradually become hybrids, and so forth…

If Hubbert’s theory did a decent job of forecasting US peak production on or about 1972, then I think it’s got a very good shot of working on a global basis in the 2007-2010 timeframe.

Remember that the US has/ had over 1M oil wells drilled over the history of its oil industry. The Middle East has about 1000 wells over its production history, according to Leonardo Maugeri’s “The Age of Oil”.

Hubbert was working with a lot better dataset when he predicted peak oil in the US. The dataset for the middle east is not nearly as good.

JS,

The city’s made money hand over fist on the coal and natural gas (and even wind) power – a major part of the city budget is utility transfers. It’s only the STNP that was a debacle. Your cheerleading aside, of course.

As for “the market will save us” – not if we continue to subsidize consumption of petroleum, it won’t.

STP 1 and 2 nuclear power is the cheapest in Austin’s portfolio and is irreplacable at its price point.

If the city wants to auction its share I’m sure there will be a long line of bidders in Texas’ deregulated electric market.

Does anyone remember that Stephen King novel, “The Langoliers”? Where the people on the plane are trapped in a kind of limbo as these time-devouring monsters show up to eat the past?

That’s what Peak Oil “critics” are – Langoliers.

They get us all worked up, eating away at our precious time and resources when we give them detailed rebuttals, despite the fact that their entire arguments are based upon false assumptions or willful ignorance.

The bottom line is that even if there was UNLIMITED petroleum in the ground to extract, it is one of the most unsustainable, environmentally destructive practices known to man and is responsible for countless human rights abuses around the globe. That alone is reason enough to find alternatives to the current system.

Any time you waste with these Langoliers trying to debate them about economics is time wasted where real, positive change could take place. And it’s also time you could spend lessening your own petroleum consumption so that they can’t hide behind the smokescreen of “hypocrisy” while you’re trying to educate others. To this end, I am in year two of my journey toward total sustainability, which you can follow at my website:

http://www.organicreform.org

If you want the Cliff’s notes version, I wrote a short essay titled “An Inside Job” that breaks down for you what I’m doing to make those changes in my own life. You can find it here:

http://organicreform.blogspot.com/2007/05/inside-job.html

Peace and health,

“Let your life be a counter friction to stop the machine. What I have to do is to see, at any rate, that I do not lend myself to the wrong which I condemn.”

-Henry David Thoreau-

Well thank you very much, Rev. Wallace. I now see the error of my ways.

Buzzcut,

This number of wells drilled is nearly meaningless. It is well known that in the US far too many wells were drilled because of the divided ownership of the pools, a classic “common property resource” problem, leading to excessive pumping out of the pools that almost certainly damaged the long run productivity of those pools, leading to the peak oil moment in the US sooner than should have (or could have) been the case.

One of the virtues of the nationalizations that happened throughout the Middle East is that one does have unitary ownership of most of the pools, and hence much more rational and productive in long run terms drilling and use of them.

Also, again, to all of you fulminating about the secretive tendencies of the Saudi monarchy, get over it. They are secretive about everything and always have been. Why should they tell outsiders anything about any of this? What right do we have to demand it of them?

And, yes, Iraq is the major obvious possible offset to the current declines, presumably able to increase production by maybe as much as 2 mbpd fairly easily, if peace and a defined legal-institutional framework were to appear. But, well, we know those are likely to be some time off into the future, for better or for worse…

When will peak oil come, hard to say, but the generally optimistic case is around 2030, well within the lifetimes of most readers here. What ever the “natural” date of peak oil is, it can be extended through slowing the growth of demand. When Peak oil comes, the supply curve turns vertical and the only way the market clears is through adjustments on the demand side. Better to work now for benign demand destruction (i.e. greater efficeny, higher CAFE standards, use of alternative fuels) than wait for destructive demand destruction (world wide depression, the whole horror show that the gloom and doomer forecast). Given the whole range of geopolitical, national defense, and very importantly ecological reason pointing in the same direction, there is no good reason not to start now from a political/policy perspective. At the very least oil is going to be more difficult to find and extract. The oil service intensity of oil extraction will continue to rise. One does not have to forcast riots in the streets of every major Capital and massive wars over reasorces, to think that overweighting oil and oil service stocks in your portfolio is a very sensible thing to do.

“STP 1 and 2 nuclear power is the cheapest in Austin’s portfolio and is irreplacable at its price point.”

When it’s operating, of course. Don’t forget the years and years of delays and outages, during which Austin Energy often had to buy power on the spot market which was far more expensive than even the least efficient plant they’ve got. Don’t forget the massive capital overruns, either.

Anybody who lives in Texas knows the STNP was a debacle. If you can salvage something out of it now, going forward, you’re doing a great thing.

http://austinchronicle.com/gyrobase/Issue/story?oid=oid%3A171962

“Because of construction and design defects, and the litigation they spawned, STP went online 10 years behind schedule and about 800% over budget”

[…]

“Conaway might consider that the downed Nuke, offline since March, is costing Austin Energy customers between $6 million and $8 million a month, says Ed Clark, spokesman for the city utility. (That doesn’t include the $4 million in repair costs that customers of the four utilities will end up sharing.) Austin has to turn to more expensive natural-gas-fired generation, and beyond that to purchases on the spot power market, to make up the lost megawatts normally generated by STP. Guess who ponies up the difference? “That’s a cost our customers have to pay,” Clark says. The first of three planned increases to Austin Energy’s customer fuel charge — in part to cover STP shutdown shortfalls — took effect July 1.”

[edited by JDH to keep the language friendly]

When did peak horse happen? How about peak steam? The fact of the matter is that there is a peak for anything but there is also always a substitute (that is until the sun expands and sucks up the earth). Does peak oil exist? Of course it does. Does it mean anything? Not much. It does is signal that the market will change(thanks Barkley).

DickF,

We are the result of a bunch of transitions, all successful, from a lower-density energy source to a higher-density energy source. Many other societies which could not find a higher-density energy source ended up in overshoot and collapsed – but, of course, they aren’t around to serve as a cautionary example.

Path bias.

There’s not any guarantee that an economically feasible energy source even at petroleum’s energy density is out there waiting for us. Nuclear + major battery improvements, for instance, doesn’t even cut it; nor does anything using hydrogen as its energy store.

Physics trumps economics.

DickF: I’m with M1EK on this. You are using a few events in history, say 5 or 6 energy transitions, and forming a law from them. You cannot justify that. Six historically unique transitions don’t imply a law of substitution for energy.

This is one of the difficulties I have with economics. Not with economics as a science. But unlike physics, people pick up terms from economics and then think they actually understand specific historical events and have the ability to predict the future by using these terms. I frequently run into people culling economic terms and assembling what seems a coherent sentence that describes how the transition from energy to what lies beyond will be a piece of cake. These arguments usually include the phrase that “we didn’t run out of whales before turning to kerosene…” and similar ideas.

Assembling gramatically correct sentences doesn’t a proof make.

As an investor, I’m interested in a good story. One that meets the “shove test,” taught me by a high school auto-shop teacher. “Jack the car up, and before crawling under or taking the tire off, give it a few good hard shoves. Then continue.”

I’ve been mentally shoving the different scenarios post-peak oil and I’ve not found a good story yet. I’m all up for hearing specific stories though, less interested in historical anecdotes. The path forward is not found in the rear view mirror.

I get a little tired when I hear educated people, such as found for example at Environmenal Economics, a site I like to visit, that tell me peak oil is a non issue, and then when it’s pointed out that recession or depressioin may result, respond that “heck, we’ve had those before.” My response? “Suddenly the terms change. Not quite a piece of cake then it is?” And when pressed, there is no good story, just wishful thinking, some basic “maybes” or “possibly.”

In other words, they don’t know. I think it not too strong to say the following: honest people should admit there is a not insignificant possibility that peak oil may be difficult.

This number of wells drilled is nearly meaningless.

Drilling a well is still the best way to determine what’s in the ground, even today. There has been a dearth of test wells in the middle east.

By dint of meticulous non emotive number-crunching, Stuart Staniford has placed the cornucopians in the one situation they’ve always hoped to avoid; having to construct a counter argument based only on the rational analysis and interpretation of available data. Sadly, they now find themselves placed in exactly the same position as blind-faith based advocates of a deity.

In short; demand is growing exponentially; discovery rates have been tailing off for decades; the custodians of Ghawar won’t release reliable independently audited figures of their remaining holdings (why?); the US is all over the middle east attempting to police only those ‘tyrants’ with oil under their feet; and we’re supposed to relax because human ingenuity will inevitably come up with some (as yet undeclared) new technologies to save the day. So, can you spot any good news in there?

As for the disinterested insights of ‘oil engineer friends’, isn’t that a bit like asking a real estate agent to talk down the property market?

Lots of interesting debate on here. As an interested layperson, my suspicion for the course of events is probably as follows (most of my figures are very speculative):

– As much of the ‘doom and gloom’ research suggests we reach ‘Peak Oil’ fairly soon (within 2 years). This is simply the point at which supply physically cannot keep up with demand.

– Due to the price elasticity, oil rises to $200-500 per barrel, leading to a global slowdown of growth particularly in booming emerging economies such as China, India, Brazil and Russia. In addition, global stock markets fall 10-20% as productivity is dampened by the higher cost of resources.

– Given the higher prices, the developed world naturally cuts back on usage to concentrate on the most important uses for oil (for example, if there was sufficient will, one could quite easily allow a large proportion of people working in tertiary industries to work from home). So long as global growth is stunted, we only need to find cut of 2-3% a year in the oil quantities that we use. We could do this relatively easily for perhaps 10-20 years, all of the time spent researching and building infrastructure for new methods of energy creation, transportation and storage.

Perhaps I’m being nave, but I think the sensible middle ground is: Peak Oil is real, when it occurs there will be something of a financial shock and global recession, but that we will (over the course of 10-20 years) continually reduce our need for oil and build up the infrastructure in other areas and life will go on.

Singo-

If that’s what you expect, you should buy oil futures (a quick check shows that you can buy as long as 84 months). That way you can triple-octuple your money in a couple of years.

I have faith in market-based transitions based on past history and an understanding of the value of information conveyed by prices. There seem to be three main views of how to approach the transition to new energy sources: one, there is nothing you can do – it will be painful; two, a new strategy should be imposed by government and three, let the market lead the way. I come down mainly on the third because increasing real prices of oil lead consumers to economize on its use and give producers incentive to produce more, or find substitutes. The prices send signals to all players that there is money to be saved or made by finding new solutions. This is decentralized teamwork at its best. If you believe that human ingenuity is the greatest resource, per Julian Simon, you will have faith that this challenge will be solved.

It’s actually more substantial than faith – really it’s confidence based on many challenges met in the past, going beyond energy.

“So long as global growth is stunted, we only need to find cut of 2-3% a year in the oil quantities that we use. We could do this relatively easily for perhaps 10-20 years, all of the time spent researching and building infrastructure for new methods of energy creation, transportation and storage.”

A. There may not BE an appropriate substitute, as there wasn’t for some societies which did not survive.

B. We may not have the money to rebuild our infrastructure appropriately. For instance, if the energy winner turns out to be nuclear over wires (assuming batteries don’t get good enough to drive SUVs 20,000 miles per year, which seems a safe bet), we’d then need to rebuild our suburban and urban infrastructure around electrified rail. Very very expensive – while at the same time we’re struggling with a deep recession or depression. Seems unlikely.

We’re going to look back and wish we hadn’t wasted “cheap oil”. It ought to have been the bootstrap technology, but instead we (in the US at least) have made it a millstone.

Singo and Berger,

The investment I’d think would be wise is a portfolio of stripper wells. Sunk costs, long production future, low risk. Do look at the pumping costs and transport to a refinery as those are variables that could affect yield. Well maintenance (“workovers”) can pinch cash flow at times but the technology is getting better. In other words, go long in oil.

As M1EK points out, the transition from free flowing oil to a rate-constrained industry and the development of alternatives will be very capital intensive. While the big boys cover the headlines, there will be a number of plays for smaller, more nimble investors and entrepreneurs.

This number of wells drilled is nearly meaningless.

What Buzzcut is ignoring is the fact that USA is a totally mature oil producer, with its own oil fields producing with knowledge that spanned within a good century (wasting a lot of rigs with the little knowledge they had), adding to the already mentioned oil-pool property division problem. With 21st century 3D seismic data analyzers, and all the techs they have at Aramco, it is very reasonable that they have pinpointed their thousand rigs in the exact location for best production. When Peak Oil arrives in Saudi Arabia, I’ll bet we’ll be observing a geometrical escalation of rig counts, as their per-rig productivity descends in inverse proportion.

There’s not any guarantee that an economically feasible energy source even at petroleum’s energy density is out there waiting for us. Nuclear + major battery improvements, for instance, doesn’t even cut it; nor does anything using hydrogen as its energy store.

Physics trumps economics.

I get the nastiest of feelings that while it is true that rarely an economist understands sufficiently well physics so that he could make a good judgment, the opposite is also true. Scientists are so focused on their narrow scope and knowledge that they don’t even grasp that the whole Earth phenomenon is too wide to understand simplistically within some theories one invents. They are always so sure of themselves, until a new theory arrives that demolishes the previous. And then, such surety doesn’t disappear. Instead it flourishes even more. And one example I like best is the common scientific theory in the 50’s that widespread pollution in the world was guiding Earth towards a cooler planet, and measures to warm it were to be politically discussed. Afterwards, science tells us the exact contrary, backed with more evidence.

Economists, on the other hand, believe that money is infinite and that the second law of thermodynamics is breakable. Well, given the forward-backwards dance that science is famous for, one can never know for sure. Once even the sound barrier was unbreakable.

There’s not any guarantee that an economically feasible energy source even at petroleum’s energy density is out there waiting for us.

But I deviated. The thought I would like to share with you is this: why do we keep concentrating our arguments on specific “statistical” coefficients as basis for our thoughts, even if we know that things aren’t at all that simple? Yes, it may be true that petroleum EROEI is unbeatable. But that is not the ONLY key point. What about the productivity index? A barrel of Petroleum is not guaranteed to create some fixed unit of products. Productivity issues are key. European use of petroleum for instance, is half of that of USA for the same GDP created. Waste is also at stake. How much of the oil we use today is not a complete waste?

Finally, I would like to stress out the importance of Combustion Engine into this discussion. People are crazy about Peak Oil, but often forget that CE is the worst kind of engine available there is, and this destroys EROEIs comments. 60 to 70% of oil power is totally wasted into heat. It was forced into us, I daresay. Like a drug we “have” to use. And buy from “them”. But it didn’t have to be like that. The first electrical vehicle was built before the oil CE engine vehicle. And the technology is available. But it has problems:

– Its cars requires less maintenance (creating a lot of jobless people);

– It doesn’t require petroleum directly (destroying a whole infrastructure of gasoline distribution economy);

– Anyone can generate electricity and thus “escape” to the system, creating havoc and despair through the minds of Big Oil power grabbers.

The tools exist. Check out the new electrical sports car from Tesla. Impressive is an understatement. If one can build such a sports car, how come a general purpose car is so “impossible”?!? “Who killed the electric car?”