Interest rates on government debt for a number of European countries– notably Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Italy, and Spain– shot up considerably during 2010-2012. Those yields have fallen significantly from their peaks, though these five countries still face higher borrowing costs than most other countries in Europe.

|

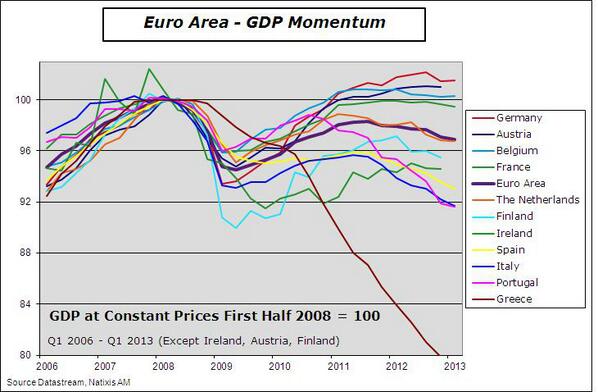

Europe has now been in an economic recession for a year and a half, with Eurostat reporting that the 17 EU countries had an average drop of real GDP of 0.6% in 2012. But real GDP in the 5 countries just mentioned fell 2.5%, while in the other 12 it grew by 0.2% during 2012.

|

It’s not hard to see a connection between the earlier fiscal problems and the current economic woes. The conservative spin is that a lack of fiscal restraint in 2004-2006 in countries like Greece and Portugal left them vulnerable to the subsequent sovereign debt scares, with the recession of 2007-2009 then putting enough new pressure on government budgets to push these countries into unsustainable debt burdens. Skyrocketing sovereign debt yields, in addition to the stresses all this placed on the banking system, meant tighter credit for every borrower, and this credit crunch was a key factor that pushed the countries back into recession.

The liberal spin is that too much fiscal constraint in 2011-2012 constituted a new contractionary shock, and that fiscal austerity is a key factor in Europe’s double-dip recession.

Both views have some validity. But I would also want to stress a third channel. One of the reasons some countries got into bigger debt problems than others is that they faced a more serious deterioration of economic fundamentals. For example, Ireland and Spain had quite low sovereign debt loads going into 2007. But the collapse of property price bubbles brought big losses to the banking systems. The main reason Ireland went from one of the lowest debt loads to one of the higher is because the government ended up injecting such a huge sum into the banking system. But as we know well from the recent U.S. experience (not to mention centuries of data from other countries), a collapse in property prices and private-sector financial distress can have lingering effects from which it takes a long time to recover. Thus both the the fiscal challenges of 2010-2012 and the recession of 2012-2013 have some common underlying causes.

Where do we stand now in terms of the fiscal outlook? Greece managed to relieve some of its burden with the PSI default in March of last year, producing the first decline in its debt/GDP ratio in 5 years. But the IMF projects that this year’s deficit and falling nominal GDP will be enough to undo all of that, with debt for 2013 a bigger multiple of GDP than it had been in 2011.

|

Even with an interest rate of 8%, paying the interest on a debt of 175% of GDP requires the country’s taxpayers to give up 14% of their annual gross income just to make interest payments on the debt, that is, just to keep debt from growing, even if the rest of the budget was somehow already balanced. That’s not going to happen– the Greek situation is clearly unsustainable. That Greece is able to borrow at such a low rate could only reflect lenders’ conviction that broader Europe is on the hook to pick up much of the bill.

Doubters of that simple arithmetic often point to Japan, whose net debt as a percent of GDP is projected by the IMF to exceed that of Greece by 2017. Yet Japan can borrow today at a 0.8% annual interest rate, and the government’s plans for further fiscal expansion appear to have boosted the country’s fortunes considerably. How can Japan get away with this while Greece cannot?

|

One key difference is that Japan has been running large current-account surpluses, while Greece has a big current-account deficit. With its high saving rate and extreme home bias for investment, Japan hasn’t needed to rely on international lenders to fund its budget deficit. Another is that Japan, unlike Greece, can pay its bills simply by creating more currency. And if currency creation does lead to higher inflation, a little inflation would be quite helpful for the Japanese economy. But it will be very interesting to see how markets adjust to the new reality that Japan is going to experience some inflation. Particularly with a declining Japanese saving rate, Japan’s fiscal situation is no more sustainable in the long run than Greece’s, and something has to give here.

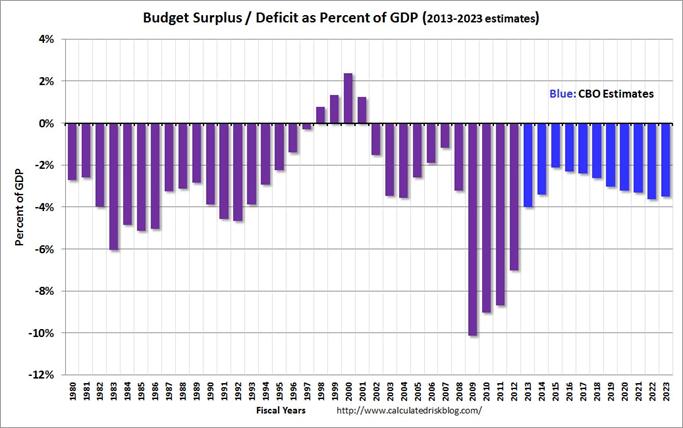

And what’s the latest outlook for the U.S. fiscal situation? The U.S. Congressional Budget Office has just released new budget projections for the next decade, which are a little more favorable than its previous assessment. The CBO now anticipates that U.S. deficits will fall significantly as a percent of GDP over the next few years before beginning to rise again each year after 2016.

|

The latest CBO projection implies that the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio will fall for the next few years and then start to rise.

|

The primary factor driving the rising deficits and debt after 2016 is the CBO’s assumption that interest rates will start to return to more historically normal levels. The current low interest rate means that the total interest expense on U.S. debt is currently fairly low despite our high debt levels. But the CBO is projecting that as interest rates rise, by 2020 net interest expense will exceed the total defense budget and exceed total nondefense discretionary spending.

|

Even if it’s true that a lack of fiscal restraint by Greece and Portugal in 2004-2006 contributed to their current woes, that does not imply that fiscal contraction in 2013 is going to help them. The time for relevant policy advice from that insight would have been 2004-2006 when there was still a chance to do something about it, not 2013 when there are no good options available.

And I believe that it would be a mistake if the U.S. were to allow government debt to grow faster than GDP after 2016.

As you know, The Economist ran online a number of comments on these issues mostly in regard ECB support for periphery nation credit and banking. The one I thought most persuasive was by William Porter from Credit Suisse, who essentially says that we have an effective (guesstimate) 30% haircut sitting there that can’t be taken because of the Euro.

Not on point, but I just finished reading a review of literature and archeology of Briton in the Dark Ages and note that the collapse of Roman society there seems directly connected to the withdrawal of the medium of exchange; the Emperor’s court moved south back to Italy, exchange completely dried up – for more complicated but related reasons – and there aren’t new coins found. The periphery, particularly Greek, situation seems in some ways like this in the mirror.

For example, Ireland and Spain had quite low sovereign debt loads going into 2007. But the collapse of property price bubbles brought big losses to the banking systems. The main reason Ireland went from one of the lowest debt loads to one of the higher is because the government ended up injecting such a huge sum into the banking system.

Yes. This is a point that can’t be stressed enough. Greece is not Italy is not Germany is not Spain is not Iceland is not Ireland is not France. There are many ways a country can stumble into a deep recession. The Greek government was reckless before 2007, but the Spanish and Irish governments were not. In the case of Spain it was, to a large extent, the Germans that drove up Spanish real estate prices. In Ireland it was a reckless private sector that was most responsible.

That Greece is able to borrow at such a low rate could only reflect lenders’ conviction that broader Europe is on the hook to pick up much of the bill.

One way that Europe could help pick up the bill is if the northern core agreed to slightly higher domestic inflation. That would help align labor productivity differentials between the core and the periphery.

The time for relevant policy advice from that insight would have been 2004-2006 when there was still a chance to do something about it, not 2013 when there are no good options available.

That same advice applies to the US as well. The time for fiscal balancing should have been before the Great Recession, not during it.

And I believe that it would be a mistake if the U.S. were to allow government debt to grow faster than GDP after 2016.

If you are choosing 2016 as a reasonably likely date for when we should expect the economy to return to normal, then I would agree; although I would prefer to see an exit strategy framed in terms of conditions (e.g., 6.5% unemployment) rather than dates. One risk we face is that the Fed will withdraw monetary accommodation too soon. Right now monetary policy is helping to counteract some of the current fiscally contractionary policies, but some at the Fed are making noises about pulling the plug this summer. I think that would be a mistake. Monetary policy should stay accommodative until we no longer need fiscal policy. Otherwise the two policies just end up defeating one another. The point is that monetary and fiscal policies should be working in a coordinated way.

What if the U.S. implemented something similar to Switzerland’s “debt brake” rule?

On a separate and related note, looking at the European nations that have seen their GDP decline since 2010, how much of that is the result of self-inflicted wounds from implementing tax-hike heavy “austerity” programs?

“But as we know well from the recent U.S. experience (not to mention centuries of data from other countries), a collapse in property prices and private-sector financial distress can have lingering effects from which it takes a long time to recover.”

Um….what *precisely* is the primary source of these “centuries” of property price data to which you allude?

I do not recall Chapter 10 of Reinhart and Rogoff (i.e. the Banking Crisis chapter) doing much hard analysis of property prices. I was also not aware of centuries-long time series of aggregate property price (with the exception of the series that the Norges Bank has put together for some Norwegian cities. See http://www.norges-bank.no/en/price-stability/historical-monetary-statistics/house-price-indicies/)

“Japan’s fiscal situation is no more sustainable in the long run than Greece’s.”

I missed the reasoning that led you to that conclusions.

You’ve noted that Greece’s interest costs alone are running 14% of GDP, that this interest rate seems artificially low (probably due to the roles of ECB and EU), and that Greece faces the additional handicaps of (a) requiring foreign capital inflows to finance its debt, and (b) borrowing in a current it cannot print. You then seem to say that Japan’s current monetary stimulus need not cause inflation and, if it does, that might be good for growth.

I’m puzzled by how you move from such a contrast to your conclusions about long-run equivalence. What’s driving that? Are you convinced that their financing costs must converge? that their economic growth rates must? Are you assuming another Greek default that brings their debt down to “levels as manageable as Japan’s”? or are you simply saying that you are certain that Japan must default?

Japan and Greece are such different situations it’s very difficult to compare them. But only if you define unsustainable as a strictly binary property can you say that Japanese borrowing isn’t more sustainable than Greece’s.

Greece has already exhausted its ability to borrow from any non-political lenders. Its ability to continue borrowing is a purely political matter. When official lenders stop lending to Greece, Greece won’t be able to borrow. In a nutshell, Greece has been given a deadline by when it should have no deficit and thus no need to borrow. Its debt is almost all very long-term and low interest now, so there’s not much to roll over anytime soon, except short-term bills, the quantity of which is capped. Greece won’t be able to borrow any important amount from private markets for many years.

Japan could carry on borrowing for some time, but it has chosen to instead have the central bank finance its large deficits. So the questions now are different: how sustainable is Japan’s monetary financing of its deficits, and if and when monetary financing is called off, will the Japanese government be able to go back to rolling over its debts by selling to the public? The rising interest rates on JGBs points to a serious problem emerging.

The CBO is sadly useless, but definitely the US will have a problem with interest costs if and when interest rates rise.

Tom: “…only if you define unsustainable as a strictly binary property can you say that Japanese borrowing isn’t more sustainable than Greece’s…..Japan could carry on borrowing for some time, but it has chosen to instead have the central bank finance its large deficits.”

I simply don’t understand. That sounds like a contradiction. Precisely why do you think that Japan can’t finance its deficits?

We have a global environment of reaching for yield. Many risky assets are giving yields in the 4% to 6% range, which is low by historical standards.

This reaching for yield allows countries like Vietnam, Romania and even Greece to lower their interest rate.

The consequence is increasing global risk, in case of problems.

My view is that interest rates from the central banks should rise to offset this problem. Here is a post of the model behind that thinking…

http://effectivedemand.typepad.com/ed/2013/05/monetary-policy-of-effective-demand-the-basics.html

slugbaits: “Right now monetary policy is helping to counteract some of the current fiscally contractionary policies”

Call it what it is please; rewarding the gamblers who bet wrong, at the expense of the savers.

Greece does not pay 8% interest, but some 2.5%, because practically all its debt is to the Eurozone.

So they are basically paying close to zero interest, after inflation.

Greece will be for many years a client of the Eurozone countries.

This is just one more example, that american economists, just looking at superficial numbers, come practically always to weird conclusions with respect to Europe

To compare a Greece with practically no industry to Japan, leeds to bizarre results

@Simon – Yes, you’re misreading something. There’s no contradiction. I’m saying Japan’s borrowing is more sustainable than Greece’s.

To clarify, Japan could continue for some time to finance its deficits by borrowing from the public, if it wanted to. Domestic savings is sufficient and real rates on JGBs are relatively high for developed economy public debt. The problem is the crowding out effect. So instead Japan’s central bank is financing the government deficit, in an attempt to suppress the currency, boost inflation and stimulate the economy. Sustainability of borrowing from the central bank is a very different question than the sustainability of borrowing from a market. The main issues are inflation and malinvestment, not interest costs, which are deferred until if and when the central bank stops financing the deficit. The government doesn’t really pay to borrow from the central bank, as the central bank refunds its interest earnings to government.

We have little guidance from history as other countries that have done what Japan is doing were developing economies with growing populations. They generally experienced high inflation and rapid devaluation, which overall were disastrous but reduced their domestic currency debts. Japan’s having some devaluation but relatively little given the scale of its monetary financing. Inflation impact is still an open question.

Meanwhile the government is continuing to borrow from the market to roll over the bulk of its outstanding debt that’s not held by the central bank. That’s where we’re seeing JGB rates rise. The fact that rates are rising could be seen as success in creating inflation expectations, but if rates go up faster than actual inflation, which is what we’ve seen so far, that will add to the government’s real interest costs, making the deficit even bigger and making it more difficult to end central bank financing of deficits and go back to paying market rates to finance deficits. Keep in mind that part of Abenomics is a promise to rein in the deficit after a couple years. That’s looking doubtful.

Slug wrote:

The Greek government was reckless before 2007, but the Spanish and Irish governments were not.

Slug, this is an absurd statement even for you. Spain jumped on the green job bandwagon long before unemployment was above 20%. Studies showed that for every one green job created Spain was losing 2.2 jobs in the real economy yet they continued in their illogical belief that green jobs was their salvation. Now unemployment in Spain is absurdly high. If that is not government recklessness I don’t know what is.

Now maybe you meant something specific for Greece relative to Spain and Ireland, but in truth the EEC has been one central planning economic disaster after another. Using the common euro has not created the problem, but has exposed the problem earlier than if each country had the white-wash of a government controlled state currency they can inflate.

Ricardo: The EEC???

Simon van Norden: You have a valid point. Evidence on the lingering effects of a property-price collapse comes primarily from the 20th and 21st centuries. On Japan, please see pages 24 and 44 (and the references therein) of this paper.

genauer and others: According to Bloomberg, somebody is out there right now offering to buy Greek debt at 8.26%. Notwithstanding, if you or any other readers can point me to a breakdown of 2013 Greek borrowing by lending source I would be most appreciative.

JDH wrote:

The conservative spin is that a lack of fiscal restraint in 2004-2006 in countries like Greece and Portugal left them vulnerable to the subsequent sovereign debt scares, with the recession of 2007-2009 then putting enough new pressure on government budgets to push these countries into unsustainable debt burdens.

The liberal spin is that too much fiscal constraint in 2011-2012 constituted a new contractionary shock, and that fiscal austerity is a key factor in Europe’s double-dip recession.

Professor I know that this has become the normal way of expressing this but it is very inaccurate and misleading.

Conservative economics is actually when the government attempts to control the economy and maintain stability through manipulation of spending either increasing or decreasing. Both of these approaches are central planning and conservative.

Liberal economics allows traders the freedom to trade in markets. Neither of these approaches is based on liberal economics. Both are conservative central planning approaches to economics. Both lead to declines in a productive economy because both create wedges to markets and so hinder them from working at optimum.

It would be more accruate to use “austerity” versus “quantitative easing.” Both of these imply central planning policies.

Menzie,

European Economic Community. You can change it to EEU if you want.

When is the default of one country triggering the critical mass driving to the defaults of more than one country? Are those defaults coming jointly or severally? A concern and it is difficult to find through papers a quantitative definition of this pivotal point.

The sensitivity of the public debts kept current through age is represented in one chart that is the Historical public debts/Revenues ratios (source zero hedge Sovereign defaults past and present in one chart ) and Japan is not looking better through this prism. Before being tempted to challenge the data and outcomes of Z. hedge, it may be worth to remember the definition of hidden costs or the hidden debts that include dressing up the public accounts (source: from financial crash to debts crisis Reinhart, Rogoff) and also leaving in the private sector a significant percentage of debts to GDP that will never be repaid. The size of the financial sector to GDP may and will come to haunt the sovereign debts.

Bluntly the question is not, if major sovereign risk will default but when ? and how other elements of the links will behave?

JDH, I just googlet:

http://www.pdma.gr/index.php/en/public-debt-strategy/public-debt/composition-of-debt/composition-by-instrument

please also take a look at “bond characteristics” and “benchmark bonds outstanding”. LOL

If you use something like comdirect.de and search for griechenland, you get some idea, of volumes, coupons, maturity profiles.

This is all gambling money of the leftovers of the

government bankruptcy on privately held debt, with a CDS recovery rate of 21.5%

It is a good example, that all those rienhart/rogoff tables and similar do not really tell you that much.

If you want to look at the public debt of THE benchmark, take http://www.deutsche-finanzagentur.de/fileadmin/Material_Deutsche_Finanzagentur/PDF/Aktuelle_Informationen/kredit_renditetabelle.pdf

a just 9k pdf file, take a look at the interest rates and at the volumes traded daily

JDH Thank you for the very interesting paper. So on Japan, then, your argument is simply that Japan cannot continue to run deficits on the order of 9% of GDP forever, but not that default is yet inevitable or even probable. Is that about right?

Looking at some spline curves through yearly OECD data tells you next to nothing, if you do not understand, why there are certain jumps, coming from realizing accumulated debt in state owned companies, cleaning up the national statistics. You are like some ballet dancers, trying to understand and cross the swamp.

For Greece interest rates, I googlet http://www.eurobank.gr/Uploads/Reports/GREECE%20MACRO%20FOCUS%20December%2013%202012.pdf

„Following the recent Eurogroup announcements, the average interest rate on all euro area loans expected to be disbursed to Greece by the end of this year (in the context of both the 1st and 2nd programmes) falls to pretty concessional levels, i.e., slightly below than 1.80%, according to our estimates.”

In principle, you could have googlet that the same way as me, but if you do not understand the politics, you do not know, what you should be looking for. GIGO Garbage in garbage out

“And I believe that it would be a mistake if the U.S. were to allow government debt to grow faster than GDP after 2016.”

Get ready for a mistake.

“Precisely why do you think that Japan can’t finance its deficits?”

Because their population is old and is quickly turing from savers to spenders. When the native population stops saving and starts consuming in retirement, who is going to fund JGB’s at 1%? Nobody. Then interest rates spiral out of control and Japan collapses. The US will have the same problem, albeit not as bad. And no, you can’t print your way out of nobody working.

This article is badly confusing cause and effect. A huge component of the US Interest rate is expected future growth. You can also see this in fluctuations in commodities.

In general, if expectations about future growth are low, interest rates will remain low. However, if growth increases interest rates may as well.

What every damn analysis I read about the budget fails to consider is how these two are related. If growth is high, it is true intrest rates will likely grow, but the overall effect is likely to result in lower not higher deficits. Articles like this one drive me crazy because the only consider one variable.

I submit that if the US grows at 4% long term interest rates will rise. BUT this rise will be more than outwieghed by the increase in revenue resulting from growth.

The more fundemental problems are the US current account deficit and the structural problems resulting from increasing inequality (which in turm slows demand given the relative MPC’s of wage earners). These are the real problems.

But it will be very interesting to see how markets adjust to the new reality that Japan is going to experience some inflation. Particularly with a declining Japanese saving rate, Japan’s fiscal situation is no more sustainable in the long run than Greece’s, and something has to give here.

I couldn’t agree more. Another reason there will be upward pressure on yields, in addition to the demographic problem and increasing trade deficits, is the new inflation target. Negative real yields will persuade some individual and institutional investors to move funds out of JGBs into other domestic assets or foreign bonds. Real yields in Japan have been negative only twice in the last 20 years, 97-98 and 2008, for about 6 months each time. With the central bank targeting 2% inflation, that implies a real yield of -1.1% (with the 10-year JGB at 0.9%) – hardly appealing. The average real yield over the 20-year period is 1.8%, which would mean an unsustainable 3.8% yield on the JGB with inflation at 2%.

Japan just needs to print money and spend it. This will increase the velocity of money. If they merely printed enough and spend enough on infrastructure and wealth redistribution to the poor, they would all become very rich.