Here’s the introduction to a new paper I just finished:

This year the oil industry celebrated its 155th birthday, continuing a rich history of booms, busts and dramatic technological changes. Many old hands in the oil patch may view recent developments as a continuation of the same old story, wondering if the high prices of the last decade will prove to be another transient cycle with which technological advances will again eventually catch up. But there have been some dramatic changes over the last decade that could mark a major turning point in the history of the world’s use of this key energy source. In this article I review five of the ways in which the world of energy may have changed forever.

Below I provide a summary of the paper’s five main conclusions along with a few of the figures from the paper.

1. World oil demand is now driven by the emerging economies.

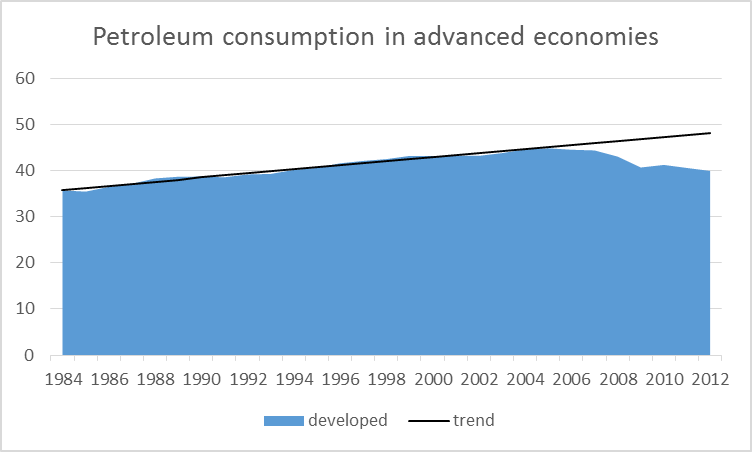

Petroleum consumption in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Japan, 1984-2012, in millions of barrels per day. Black: linear trend estimated 1984-2005. Data source: EIA. Figure taken from Hamilton (2014).

2. Growth in production since 2005 has come from lower-quality hydrocarbons.

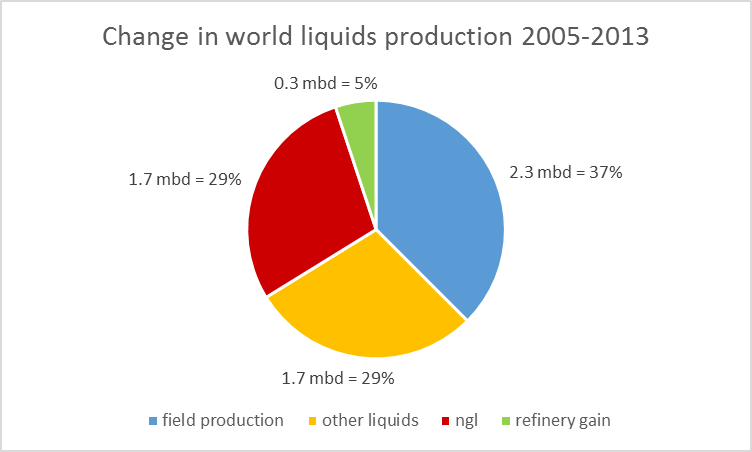

Amount of increase total liquids production between 2005 and 2013 that is accounted for by various components. Data source: EIA. Figure taken from Hamilton (2014).

3. Stagnating world production of crude oil meant significantly higher prices.

![Prices of different fuels on a barrel-of-oil-BTU equivalent basis (end of week values, Jan 10, 1997 to Jul 3, 2014). Oil: dollars per barrel of West Texas Intermediate, from EIA. Propane: FOB spot price in Mont Belvieu, TX [(dollars per gallon) x (1 gallon/42 barrels) x (1 barrel/3.836 mBTU) x 5.8], from EIA. Ethane: FOB spot price in Mont Belvieu, TX [(dollars per gallon) x (1 gallon/42 barrels) x (1 barrel/3.082 mBTU) x 5.8], from DataStream. Natural gas: Henry Hub spot price [(dollars per mBTU) x 5.8], from EIA. Figure taken from Hamilton (2014).](https://econbrowser.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/iaee3.png)

Prices of different fuels on a barrel-of-oil-BTU equivalent basis (end of week values, Jan 10, 1997 to Jul 3, 2014). Oil: dollars per barrel of West Texas Intermediate, from EIA. Propane: FOB spot price in Mont Belvieu, TX [(dollars per gallon) x (1 gallon/42 barrels) x (1 barrel/3.836 mBTU) x 5.8], from EIA. Ethane: FOB spot price in Mont Belvieu, TX [(dollars per gallon) x (1 gallon/42 barrels) x (1 barrel/3.082 mBTU) x 5.8], from DataStream. Natural gas: Henry Hub spot price [(dollars per mBTU) x 5.8], from EIA. Figure taken from Hamilton (2014).

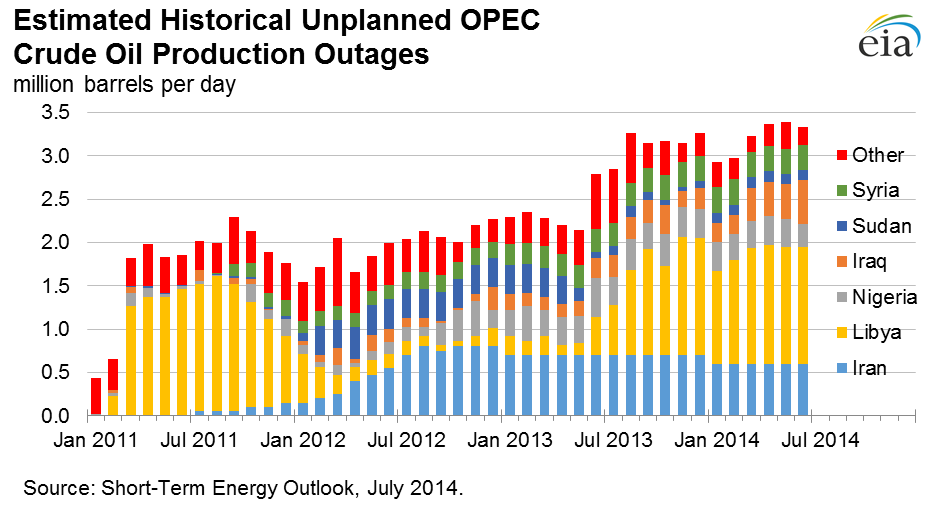

Global oil supply disruptions, Jan 2011 to June 2014. Source: constructed by the author from data provided in EIA, Short-Term Energy Outlook. Figure taken from Hamilton (2014).

5. Geological limitations are another reason that world oil production stagnated.

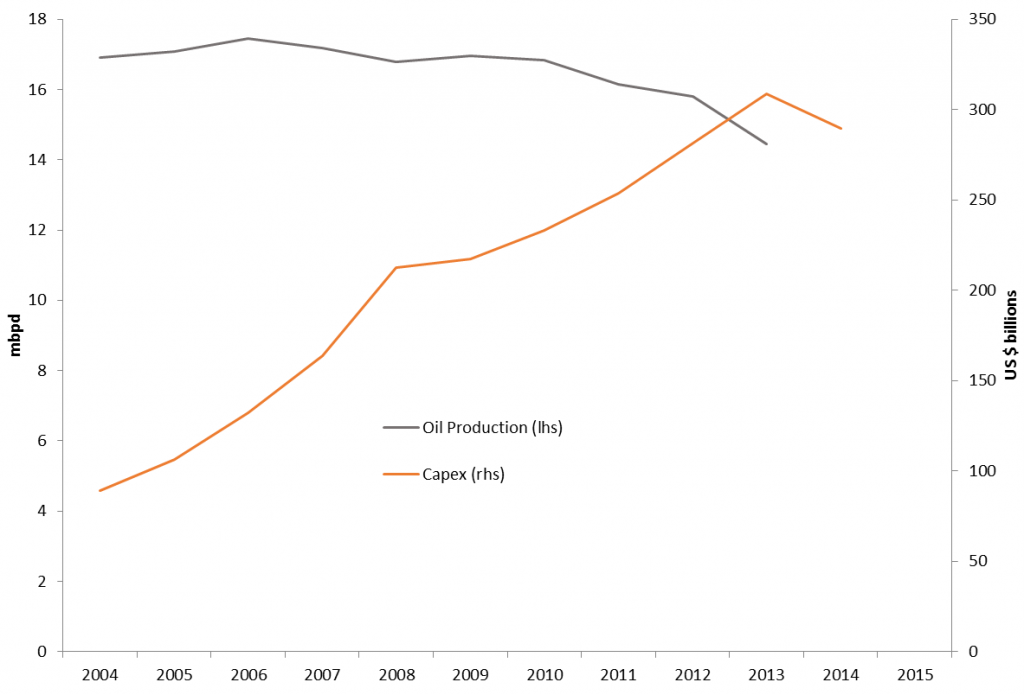

Total oil production and capital expenditures for the major international oil companies, 2004-2013. Includes XOM, RDS, BP, CVX, STO, TOT, PBR, PTR, ENI, REP, and BG. Source: updated from Kopits (2014). Figure taken from Hamilton (2014).

And here is the paper’s conclusion:

Although the oil industry has a long history of temporary booms followed by busts, I do not expect the current episode to end as one more chapter in that familiar story. The run-up of oil prices over the last decade resulted from strong growth of demand from emerging economies confronting limited physical potential to increase production from conventional sources. Certainly a change in those fundamentals could shift the equation dramatically. If China were to face a financial crisis, or if peace and stability were suddenly to break out in the Middle East and North Africa, a sharp drop in oil prices would be expected. But even if such events were to occur, the emerging economies would surely subsequently resume their growth, in which case any gains in production from Libya or Iraq would only buy a few more years. If the oil industry does experience another price cycle arising from such developments, any collapse in oil prices would be short-lived.

My conclusion is that hundred-dollar oil is here to stay.

can emerging economies continue to grow at $100 barrel oil? or will they need to explore other options which are more reliable and cheaper in the long run than the current prospects of oil? if what you imply is true, and oil will only rise in trend long term, it probably opens the door to non-oil sources for the emerging markets. unless you can justify an emerging market can continue to grow under increasing energy costs. or demand from advanced economies drops enough to assist the emerging market growth.

What has happened is clear. Normalized liquids consumption for China, India, (2005) Top 33 Net Oil Exporters and the US from 2002 to 2012, versus annual Brent crude oil prices:

http://i1095.photobucket.com/albums/i475/westexas/Slide14_zpsb2fe0f1a.jpg

China was up to 204% of 2002 consumption in 2013 (India and the Top 33 also showed increases). The US also showed an increase, up to 96% of the 2002 level, but US consumption remained well below both the 2002 and 2005 levels.

What is less clear is what will happen, and what I call the $64 Trillion question is what happens from 2012 to 2022, and in future years, but it would appear that we continued to slide, in 2013, toward a point in time that we cannot arrive at, i.e., when China & India alone would theoretically consume 100% of GNE. At the 2005 to 2012 rate of decline in the GNE/CNI Ratio, China and India only would theoretically consume 100% of GNE in the year 2030, theoretically leaving no net oil exports available to about 155 net importing countries.

In any case, here is the problem: Given an inevitable ongoing decline in GNE, unless the Chindia region cuts their consumption of GNE (their net imports of oil, CNI) at the same rate as the rate of decline in GNE, or at a faster rate, the resulting ANE decline rate will exceed the GNE decline rate and the ANE decline rate will accelerate with time (on a year over year basis).

ANE–the volume of Global Net Exports of oil available to importers other than China & India–has already fallen from 41 mbpd in 2005 to 35 mbpd in 2012 (and I estimate it was down to between 33 and 34 mbpd in 2013).

Some definitions:

Net Exports = Production of total petroleum liquids + other liquids less total liquids consumption (EIA data base)

Global Net Exports (GNE) = Combined net exports from (2005) Top 33 net oil exporters, total petroleum liquids + other liquids (EIA)

Available Net Exports (ANE) = GNE less Chindia’s Net Imports (CNI)

And in support of Chart #2 above, a copy of my reply to the previous article follows. Note that field production above means crude + condensate (C+C).

Did Global Crude Oil Production* Peak in 2005?

*45 and lower API gravity crude oil, not crude + condensate

In my opinion, it is very likely that actual global crude oil production (45 or lower API gravity crude oil) peaked in 2005, while global natural gas production and associated liquids (condensates & natural gas liquids) have so far continued to increase.

I’ve always thought it odd that when we ask for the price of oil, we get the price of 45 or lower API gravity crude oil, but when we ask for the volume of oil, we get some combination of crude oil + condensate + NGL (Natural Gas Liquids) + biofuels + refinery gains.

This is analogous to asking a butcher for the price of beef, and he gives you the price of steak, but if you ask him how much beef he has on hand, he gives you total pounds of steak + roast + ground beef. Shouldn’t the price of an item directly relate to the quantity of the item being priced, and not to the quantity of the item plus the quantity of (partial) substitutes?

In any case, the closest measure of global crude oil production that we have is the EIA data base that tracts global Crude + Condensate (C+C). In regard to this data base, a key question is the ratio of global condensate to C+C production. Unfortunately, we don’t appear to have any global data on the Condensate/(C+C) Ratio. Note that when the EIA discusses “crude oil” they are talking about C+C.

Insofar as I know, the only complete Condensate/(C+C) data base, from one agency, is the Texas RRC data base for Texas, which showed that the Texas Condensate/(C+C) ratio increased from 11.1% in 2005 to 15.4% in 2012. The 2013 ratio (more subject to revision than the 2012 data) shows that the 2013 ratio fell slightly, down to 14.7%, which probably reflects more focus on the crude oil prone areas in the Eagle Ford. The EIA shows that Texas marketed gas production increased at 5%/year from 2005 to 2012, versus a 13%/year rate of increase in Condensate production. So, Texas condensate production increased 2.6 times faster than Texas marketed gas production increased, from 2005 to 2012.

The EIA shows that global dry gas production increased at 2.8%/year from 2005 to 2012, a 22% increase in seven years. If the increase in global condensate production only matched the increase in global gas production, global condensate production would be up by 22% in seven years. If global condensate production matched the 2005 to 2012 Texas rates of change (relative to the global increase in gas production), global condensate production would be up by about 67% in seven years.

In any case, we don’t know by what percentage that global condensate production increased from 2005 to 2012. What we do know is that global C+C production increased at only 0.4%/year from 2005 to 2012. In my opinion, the only reasonable conclusion is that rising condensate production–a byproduct of natural gas production–accounted for virtually all of the increase in global C+C production from 2005 to 2012, which implies that actual global crude oil production –from crude oil reservoirs–was flat to down from 2005 to 2012, as annual Brent crude oil prices doubled from $55 in 2005 to $112 in 2012.

The following chart shows normalized global gas, NGL and C+C production from 2002 to 2012 (2005 values = 100%).

http://i1095.photobucket.com/albums/i475/westexas/Slide1_zps45f11d98.jpg

The following chart shows estimated normalized global condensate and crude oil production from 2002 to 2012 (2005 values = 100%). I’m assuming that the global Condensate/(C+C) Ratio was about 10% for 2002 to 2005 (versus 11% for Texas in 2005), and then I (conservatively) assume that condensate increased at the same rate as global gas production from 2005 to 2012, which is a much lower rate of increase in condensate (relative to the increase in gas production) than what we saw in Texas from 2005 to 2012.

http://i1095.photobucket.com/albums/i475/westexas/Slide2_zpse294f080.jpg

Based on foregoing assumptions, I estimate that actual annual global crude oil production (45 or lower API gravity crude oil) increased

from about 60 mbpd (million barrels per day) in 2002 to about 67 mbpd in 2005, as annual Brent crude oil prices doubled from $25 in

2002 to $55 in 2005.

At the (estimated) 2002 to 2005 rate of increase in global crude oil production, global crude oil production would have been up to

about 90 mbpd in 2013.

As annual Brent crude oil prices doubled again, from $55 in 2005 to an average of about $110 for 2011 to 2013 inclusive, I estimate

that annual global crude oil production did not materially exceed about 67 mbpd, and probably averaged about 66 mbpd for 2006 to

2013 inclusive.

Jeffrey, if possible, perhaps you could show data in per capita terms, as this is a critical factor when examining overall systemic net exergetic stock and flows at scale and change rates, i.e., a more comprehensive measure of an economy’s capacity to sustain (or not) the necessary work to support a given population.

Thanks.

Here’s the Wikipedia entry on global population trends:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_population

It would appear that the net increase in global population from 2005 to 2013 was from about 6.6 billion to 7.2 billion (a 1.1%/year net rate of increase). Basically, in the four year time periods between US presidential elections, the net increase in global population is approximately equivalent to current US population.

Based on the seven year 2005 to 2012 rate of decline in the (2005) Top 33 net exporters’ ECI Ratio (3.75 to 3.26, a rate of decline of 2%/year), I estimate that post-2005 Global CNE (Cumulative Net Exports) were about 538 Gb, with about 113 Gb (21%) having been shipped from 2006 to 2012 inclusive. I estimate that remaining post-2005 Global CNE were down to about 76% at the end of 2013.

So, I estimate that as the global population increased by 9% from 2005 to 2013, we burned through about one-fourth of the total remaining volume of Global Net Exports of oil.

Incidentally, I estimate that the rate of depletion of our remaining supply of Global CNE accelerated from about 3.0%/year in 2006 to 3.8%/year in 2013.

Thank you, sir.

Since 2005, world “total oil supply” is down 3% per capita: http://tinyurl.com/mmaw5kr

Crude + C is down 6% per capita: http://tinyurl.com/mu8fkay

World real GDP per capita has grown 1%/year since 2005 (half the long-term rate) and 0.6%/year since 2007 (30% of the long-term rate):

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD/countries?display=graph

But in PPP terms, growth has been at 1.9%/year since 2008, albeit HEAVILY skewed by growth in China vs. growth near 0% for 65-70% of world GDP:

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.KD/countries/1W-CN-US-XC-JP-BR?display=graph

US refineries are running all out: http://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.cfm?id=17251

China uses a lot of coal:

Chart: http://www.eia.gov/countries/analysisbriefs/China/images/total_energy_consumption.png

Perhaps, the U.S. should be using more:

Chart: http://barryonenergy.files.wordpress.com/2013/06/figure-1a.jpg

Clean coal technologies:

http://americaspower.org/clean-coal-technologies

Coal is expensive: occupational health costs, CO2, sulfur/acid rain, mercury in food, water consumption, adding up to $.18 per kWh ($345B/year):

“The United States’ reliance on coal to generate almost half of its electricity, costs the economy about $345 billion a year in hidden expenses not borne by miners or utilities, including health problems in mining communities and pollution around power plants, a study found.

Those costs would effectively triple the price of electricity produced by coal-fired plants, which are prevalent in part due to their low cost of operation, the study led by a Harvard University researcher found.

“This is not borne by the coal industry, this is borne by us, in our taxes,” said Paul Epstein, a Harvard Medical School instructor and the associate director of its Center for Health and the Global Environment, the study’s lead author.

“The public cost is far greater than the cost of the coal itself. The impacts of this industry go way beyond just lighting our lights.”

http://uk.reuters.com/article/2011/02/16/us-usa-coal-study-idUKTRE71F4X820110216?rpc=401&feedType=RSS&feedName=environmentNews&rpc=401

or here’s the link to the pay-wall-protected version if desired: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05890.x/full

These costs are large even if you don’t accept that Climate Change is costly – the cost table on page 92 (20 of 26) includes 3.06 cents for CO2, only 17% of the total.

———————————————————————————————————————

Two new Carbon Capture and Sequestration (CCS) plants are demonstrating that CCS is extremely expensive.

The first is in Saskatchewan. It’s expected to cost $1.2B, and have a nominal capacity of 110MW. The second, in Mississippia, is called Boundary Dam. Bounday Dam will cost about $5 (up from the initial estimate of $2.4B) for a capacity of 565MW.

If we assume an average utilization of 75% (a little higher than the industry average) we get an overall cost per average Watt of $12.25. If we assume 7% interest and a 30 year life, that gives us a cost for capital alone of 11.3 cents per kWh.

These plants are selling their CO2 output for Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR), but that’s not scalable to a large number of plants: the market for EOR could absorb only two or three percent of coal CO2, and long distance movement of CO2 for this purpose would be very expensive.

The article suggests that the IPCC is pushing for biomass with CCS, but I strongly suspect it makes much more sense just to grow biomass and bury it, rather than trying to capture the carbon with CCS. That’s after we move to low-CO2 generation first, of course – it’s always easier to just not emit CO2 than it is to capture and sequester it.

http://www.technologyreview.com/news/527036/two-carbon-trapping-plants-offer-hope-of-cleaner-coal/

Electric cars, and many countries, will need coal.

More demand for natural gas, including natural gas vehicles, will raise natural gas prices.

Coal May Pass Oil As World’s No. 1 Energy Source By 2017, Study Says

NPR

December 18, 2012

“Despite a slowdown in U.S. consumption, coal is poised to replace oil as the world’s top energy source — possibly in the next five years, according to the International Energy Agency. The rise will be driven almost entirely by new energy demands in China and India, the IEA says.

Together, China and India will account for more than 90 percent of the rise in demand for coal over the next five years, according to the IEA.

The agency predicts that coal’s growth trend will hold everywhere in the world except the United States, where it says the wide availability of cheap natural gas brought a decline in coal demand.

By 2017, the IEA also expects India to surpass the U.S. as the world’s second-largest coal consumer.

Europe’s coal consumption is also rising…demand for coal has surged as a result of sky-high natural-gas prices in international markets and declining output from nuclear power as Germany phases out its fleet of reactors.”

http://www.npr.org/blogs/thetwo-way/2012/12/18/167546881/coal-may-pass-oil-as-worlds-no-1-energy-source-by-2017-study-says

Electric cars, and many countries, will need coal.

Not really. Replacement of the entire US fleet of passenger vehicles would only increase electrical consumption by about 20%. Over 30 years, that’s only .7% per year. That’s really easy to supply with wind and solar. Or natural gas or nuclear.

More demand for natural gas, including natural gas vehicles, will raise natural gas prices.

Could be. Given that NG is much cleaner than coal, I don’t really see why that’s a problem.

Coal May Pass Oil As World’s No. 1 Energy Source By 2017, Study Says

Yes, the world has a lot of coal. That’s not a good reason to use such an expensive, risky, dirty energy source.

NG, you give all of these examples but never a link…Why is dat?

“Coal is expensive: occupational health costs, CO2, sulfur/acid rain, mercury in food, water consumption, adding up to $.18 per kWh ($345B/year):”

“Not really. Replacement of the entire US fleet of passenger vehicles would only increase electrical consumption by about 20%.”

My understanding, is that there is not enough production capacity to fuel

300 millions vehicles on a daily bases..

And have you figure the risky pollution cost in doing so? Of course not since you

are an Enviro.

never a link

I gave the link for this quote: “Coal is expensive: occupational health costs, CO2, sulfur/acid rain, mercury in food, water consumption, adding up to $.18 per kWh ($345B/year):” above. Here it is again:

http://uk.reuters.com/article/2011/02/16/us-usa-coal-study-idUKTRE71F4X820110216?rpc=401&feedType=RSS&feedName=environmentNews&rpc=401

or here’s the link to the pay-wall-protected version if desired: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05890.x/full

My understanding, is that there is not enough production capacity to fuel 300 millions vehicles on a daily bases.

Ah, I’m glad you asked. Sometimes I like to wait until people ask, so that I know they’re listening. Here we go:

2.9 trillion vehicle miles traveled per year x

.3 kWhs per mile =

about 1 trillion kWhs. divide by 8760 hours per year = 99 gigawatts. That’s about 22% of the US average of about 450GW.

the risky pollution cost in doing so?

Well, best to get it from wind, solar or nuclear. Coal would be about as bad as oil, but NG would be rather better.

Of course not since you are an Enviro.

Thinking in terms of “you” vs “us” will make you not think very well. Best to just take things with a little more detachment.

U.S. Department of Energy:

“…Sounds like coal is a dirty fuel to burn. Many years ago, it was. But things have changed. Especially in the last 20 years, scientists have developed ways to capture the pollutants trapped in coal before the impurities can escape into the atmosphere. Today, we have technology that can filter out 99 percent of the tiny particles and remove more than 95 percent of the acid rain pollutants in coal.”

http://www.fossil.energy.gov/education/energylessons/coal/index.html

Two new Carbon Capture and Sequestration (CCS) plants are demonstrating that CCS is extremely expensive.

The first is in Saskatchewan. It’s expected to cost $1.2B, and have a nominal capacity of 110MW. The second, in Mississippia, is called Boundary Dam. Bounday Dam will cost about $5 (up from the initial estimate of $2.4B) for a capacity of 565MW.

If we assume an average utilization of 75% (a little higher than the industry average) we get an overall cost per average Watt of $12.25. If we assume 7% interest and a 30 year life, that gives us a cost for capital alone of 11.3 cents per kWh.

These plants are selling their CO2 output for Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR), but that’s not scalable to a large number of plants: the market for EOR could absorb only two or three percent of coal CO2, and long distance movement of CO2 for this purpose would be very expensive.

The article suggests that the IPCC is pushing for biomass with CCS, but I strongly suspect it makes much more sense just to grow biomass and bury it, rather than trying to capture the carbon with CCS. That’s after we move to low-CO2 generation first, of course – it’s always easier to just not emit CO2 than it is to capture and sequester it.

http://www.technologyreview.com/news/527036/two-carbon-trapping-plants-offer-hope-of-cleaner-coal/

“America has more coal within its borders than any other country with over 260 billion tons of coal reserves. America’s recoverable coal reserves has the energy equivalent of 900 billion barrels of oil, more than the Middle East’s known oil reserves.

http://americaspower.org/america-powered-worlds-largest-supply-coal

As I said above: yes, the US has a lot of coal. That’s not a good reason to use such an expensive, risky, dirty energy source.

Energy is needed to produce GDP.

And, fossil fuels raised living standards dramatically, along with raising life expectancies substantially.

Moreover, fossil fuels are much cleaner today than in the past, and they’ll be cleaner in the future.

Until there’s a practical (rather than a propaganda) alternative, oil, natural gas, and coal will be the bulk of our energy usage.

Energy is needed to produce GDP. And that energy can come from many sources. Of course, the US could easily cut it’s oil consumption in half with efficiency – that’s far cheaper than $100 oil.

fossil fuels raised living standards dramatically And whale oil produced a nice flame. But, both are obsolete.

fossil fuels are much cleaner today Not really. What specific pollutants do you have in mind?

Until there’s a practical (rather than a propaganda) alternative, If wind, solar and nuclear aren’t practical, why is our biggest competitor, China, building more of all of them than us or anyone else?

Nick G said “but I strongly suspect it makes much more sense just to grow biomass and bury it”

The best would be to extract some energy through pyrolysis and then bury the biochar through integrating it into cropland. This is effectively burying coal with a bonus of enhancing soil.

I do recall seeing a paper some years back that unfortunately showed that even that won’t scale enough to be more than one of many wedges to bring atmospheric carbon back down, but it is a start.

extract some energy through pyrolysis

Wouldn’t that extract some carbon? Why not maximize the carbon sequestration, and just bury sawdust/chips or other shredded biomass?

I would not call the massive intervention by SA/Kuwait/UAE in 2008 to be minor! Look at the percent of their volume withheld and the price change created. That is textbook cartel behavior. You continue to fail to quantify cartel impact. [Oh…and it is very funny how it occurred after your white paper saying OPEC did not drive prices, depletion did.]

The real story is that we are running out of cheap oil, OUTSIDE of Arabia. There is a huge amount in there and if we had atomistic free competition within the borders of Arabia, world price would crash. The futures curve being backwarded shows that current price is elevated above the natural Hotelling rule level.

Oh…and why not make a cost curve of all the world’s oil? Try. It would be an interesting analysis, even if non-trivial and prone to error. It at leasts drives thinking about segments of supply. Why didn’t you predict the shale oil from 100? (it is substantial, moves the needle, and has prevented 150-200/bbl pricing). Is there another segment that comes on line at 150? I don’t know. But you should try to think about it.

Nony: (1) In your view, why is Saudi Arabia spending so much more on drilling but not producing any more oil? (2) If you take the output of Saudi Arabia as given, how is your assessment of the situation different from the one I offer?

why is Saudi Arabia spending so much more on drilling but not producing any more oil?

I’d like to see that data – that would be a great topic for another post. This post just deals with the major oil companies, which only have access to a fraction of oil production and reservers. It would be nice to look at the national oil companies.

And Saudi net oil exports have (so far) been below their 2005 rate of 9.1 mbpd (total petroleum liquids + other liquids, EIA) since 2005.

As annul Brent crude oil prices rose from $25 in 2002 to $55 in 2005, Saudi Arabia increased their net exports from 7.1 mbpd in 2002 to 9.1 mbpd in 2005. At this rate of increase, their net exports would have been at about 18 mbpd in 2013.

As annual Brent crude oil prices doubled again, from $55 in 2005 to the $110 range for 2010 to 2013 inclusive, Saudi net oil exports have been below the 9.1 mbpd for 8 straight years. Based on BP consumption data and EIA production data for 2013, Saudi net exports were about 8.5 mbpd in 2013, versus 9.1 mbpd in 2005.

Following is a chart showing normalized Saudi production (total petroleum liquids + other liquids), net exports, ECI Ratio (ratio of production to consumption) and estimated remaining post-2005 CNE (Cumulative Net Exports) by year:

http://i1095.photobucket.com/albums/i475/westexas/Slide21_zps74c9ebac.jpg

I estimate that Saudi Arabia has shipped, in only seven years, about 37% of their post-2005 CNE. This method of estimating post-export peak CNE was too optimistic for the Six Country Case History (combined net exports from the major net exporters , excluding China, that hit or approached zero net exports from 1980 to 2010).

James:

To take your question seriously. I would have to look at the details of those numbers and analyze them to give you a response. I don’t have them at my fingertips.

I still think you fail to deal seriously with the major criticism I have for you (and have had for years). Indulge me in a thought experiment: Arabian production is host to a fractionated market of independent producers. What does your gut tell you about what would happen?

“Today you’d pay four times as much to buy a BTU in the form of oil compared to natural gas.”

A very solid paper, and well written. I want to hear more about the implications of that sentence.

One implication is that oil is obsolete for the majority of it’s current applications, especially 80% of ground transportation.

Electricity costs about 1/3 as much as oil for powering vehicles.

If the US chooses not to permit more than one LNG export plant, then yes, within the US there will inevitably be a huge turn towards electric vehicles. The electric car industry is really all about centrally burning natural gas and using electric power as a distribution medium.

Though the efficiency of the process is obviously not yet nearly good enough to achieve that 1/3 price ratio you’re claiming.

The average US car gets 22MPG. At $3.75/gallon, that’s 17 cents per mile.

The average EV gets 3 miles per kWh. At 12 cents per kWh, that’s 4 cents per mile. Less than 25% of the average US conventional car.

There are a lot of sources of electricity, including wind, solar and nuclear. Any and all of those would work, though nuclear does seem to be stagnating, due to it’s unique risks.

At the moment NG is very cheap (not including GHG emissions). That could change – wind and solar have very nicely stable costs.

Tom The electric car industry is really all about centrally burning natural gas and using electric power as a distribution medium

Perhaps, but it’s not immediately obvious to me why it would necessarily have to be that way. Electric cars would seem like a good fit for decentralized electric power generation because you have a fair amount of discretion as to when you want to recharge the batteries; i.e., it doesn’t have to be tied in with baseload.

It’s about big power plants burning natural gas because of the far lower price of natural gas and the economy of scale of big plants. If gas goes higher than current oil prices on an energy equivalence basis then you’ll see coal and nuclear revive. If you think wind and solar have great prospects you don’t know their economics.

Also a nice fit with wind and nuclear, which have a bigger share of night time power production.

If gas goes higher than current oil prices on an energy equivalence basis then you’ll see coal and nuclear revive.

Heck, gas only needs to higher than coal. We saw that to some extent recently, when gas prices rose a bit.

If you think wind and solar have great prospects you don’t know their economics.

And what economics are those? Wind is cheaper than new coal, in the US. It’s cheaper than old coal, if you just figure in a little of the indirect cost of coal. See my comment above: https://econbrowser.com/archives/2014/07/the-changing-face-of-world-oil-markets#comments-183556

Solar has reached grid-parity in many places (just google “solar power australia”), and it’s cost continues to plunge.

Nuclear, of course, has substantial risks but it’s still better than coal.

Excellent piece.

One factor that could drive down oil prices, at least temporarily, are steep US excise taxes on oil.

That would signal a credible policy commitment to conservation, something the US is currently lacking despite lots of waffling.

James is a nice guy and probably a beloved prof. Reasonably smart and a good communicator. I’m sure he is popular with students and such. Sort of a Mankiew (sp?) or DeLong type.

And I’m sure he’s seen the basics and I’m sure has taught intro micro. But for some reason, I don’t see him having internalized all the concepts. And definitely don’t see him analyze industries the way a solid analyst from Goldman or McKinsey (not the public facing ones) would disaggregate the issues. Maybe he’s a closet macro economist? (They are not as good as classical micro guys.)

I just think the guy could do a better job if he went and studied some classical commodity industries and did some more serious papers. Not this really light stuff on depletion that basically acts like people have never thought about it.

I don’t know, Nony. My work has been cited in 38,000 other academic studies. How about yours?

~400 (and not in econ, technical topic and did not stay in academia past grad school.)

You still are trying to write about an industry without showing demand and cost curves. Yeah, you’re popular and set in what you do. But I’ve worked with other very popular Ph.D. economists too. Very solid micro guys. Understand both the theory and practice of looking at industry case studies.

I know it stings, but I’m serious and not just trolling you. I don’t get the vibe from you that I have from really solid, sharp micro economists. And then when you have people in the comments with triangles of doom and ELMs and the like? Sheesh. Kopits is a good guy and has cool insights to contribute…but he also often seems not to know the basic econ 101 ideas.

Nony: I’m curious to see the link to the 400 studies that you claim have cited your work.

Why? I already said they’re nothing do with economics. And I never even tried to get into a cite-count muscle-size comparison. That was all you. ~400 not small enough? It’s 1% of yours. Tiny, tiny. 😉

P.s. I just went through the incredibly nerdy process of cutting and pasting the names of my old papers into Google scholar, looking how many cites there were for each, and filling out a flipping Excel spreadsheet. 10 pubs, 415 cites. ~400 swag not far off. 🙂

Nony: Every other factual claim you’ve made here has proven to be completely false. I for one do not believe this one either. 400 citations in Google Scholar is a much bigger achievement than I believe you are capable of, based on the lack of intellectual content in anything you have contributed in these comments. How many articles do you claim to have written? Please provide a link to just one or two that actually have some citations in scholar.google.com, in support of your claim that there are 400 such citations that could be found there. Otherwise, please abandon your pompous posturing here.

Professor Hamilton, I find your reply disingenuous and disturbing.

Hans: Whatever word it is you’re looking for, it’s clearly not “disingenuous”.

Jim is the pre-eminent macroeconomist covering oil markets. That’s why the International Energy Economists Association singled Jim out for his contributions to the field just a few weeks ago. There are others in this top group: Lutz Killian, Michael Kumhof of the IMF (vastly under-appreciated), Dermot Gately (now retired) and probably me (although I am not a professional economist). These are economists, not commodity analysts. Neither the IEA nor EIA has anyone at this level; nor do the oil companies. Nor does CERA (IHS) or PIRA.

As regards Goldman: They are clearly at sea with regards to their thinking about oil markets.

Here’s Jeff Currie, Head of Global Commodities Research at Goldman Sachs, from a July 22 note:

“Over a decade ago, there were two types of supply constraints: 1) technological constraints that prevented engineers from accessing oil they knew existed, such as shale, oil sands and ultra-deepwater and 2) political constraints such as exorbitantly high taxation in Russia, bans on foreign investment into the oil sector in places like Mexico and Saudi Arabia, bans driven by environmental goals, and outright civil unrest that made investment too risky. Either the technology or the politics had to change in order to create new supply. Think of it as a race between the engineers and politicians.

As it turned out, the engineers won.”

In natural gas, this may be true, at least in the US. And even that you have to take with a grain of salt. In the late 1990s, nat gas averaged around $2.20 / mmbtu, which should be about $3 in today’s money. Nat gas is $3.80 today. Engineers did not make natural gas cheaper in real terms, compared to the pre-2000 era. Not even in the US.

As for oil, if engineers were so successful, why have E&P costs been rising at an 11% pace after allowing for technological improvement. The engineers are not losing, they’re getting creamed, when we consider the economics of the industry as a whole. Nor is it clear that shale oil is cheap. Bernstein (who are much better analysts than the Goldman team right now) calculate the marginal shale barrel in the US at $111. WTI today was at $102.

The politicians are not throwing in the towel because the price of oil has collapsed. They are throwing in the towel because their vaunted engineers have been unable to control E&P costs. Jeff knows that. It’s in Goldman’s own reports. But he doesn’t understand the logic. Goldman doesn’t use a supply-constrained model. If you try to explain what’s going on with a demand-constrained approach, you end up with rather tortured arguments, much along the lines of Jeff’s.

If you use a supply-constrained model, it’s pretty simple. Once you get to the carrying capacity price, price increases depend on increases in purchasing power, not marginal cost. If you’re an exporting petro-state (with an NOC), you’ll be facing the same cost pressures facing the IOCs, ie, your costs will be rising faster than your revenues. If you want to increase net revenue, you have to increase production (exactly the opposite of the 2003-2011 period, when the overwhelming share of revenue increases came from increased selling prices ). Hence the pressure to open up access to heretofore closed or restricted economies (a point I make during the Q&A of my Feb. Columbia University presentation). OPEC and other exporters will need increased production to increase revenues. You should not, however, assume that production in these places is easy to increase in the short, or even medium, term.

So, if you’re thinking that Jim is somehow on the periphery of the professional debate, you’d be wrong. On the academic side, he is literally at the heart of it.

I have a how shall we say somewhat different experience with Goldman and especially McKinsey, but if there’s a particularly good report by either of them you think we should read, please point us to it or post it. If you try and claim you’ve got some great piece you can’t share I’m going to laugh.

Obviously Jim hasn’t written the be-all end-all of analyses of the global oil industry, nor does it look like he set out to. Your point about the possibility that the Gulf Arab oil cartel will break up and, what the heck, dissolve national oil companies and invite in all and sundry, could be worth considering in a more completist work as a highly unlikely but theoretically possible downward price risk.

But keep in mind the Gulf Arab countries aren’t just propping up the current price, they’re also conserving some wealth for the longer run. Sure they could knock down the price some for a while if they wanted. Estimates differ over how much lower for how much longer, and nobody really knows. But whatever their resources are, speeding up exploitation would only bring forward output and the day when their output begins to irresistably decline. To really change the long-term outlook, they’ve got to find more resources, or secretly have a lot more than they’ve been acting like they have.

I don’t have any super McK/GS studies (secret or otherwise). That wasn’t my point. My point was more about analytical approach, that you would just get from a good analyst disaggregating a problem. And, yeah, I’ve had bad experiences with both also. Not here to pump them. [Or pump myself with 1% of his citations and with no econ degrees.] If anything, my point is more that you DON’T have to have 40,000 citations and a tenured saltwater faculty position to understand basics of supply and demand industry analysis. I’m really reacting to something in how Jim looks at stuff that is not econ 101. Maybe it’s the macro versus micro (micro really is better).

Oh…and ignoring the cartel is really ignoring what is at least a big POTENTIAL factor in the price of oil. A dismissive sentence or two is insufficient analysis. It’s like ignoring steroids when looking at home run numbers.

Indulge me in the thought experiment. Saudi Arabian oil produced by a large number of atomistic producers in free competition. Do you really think their would be no price impact? Would it go up (lack scale)? 😉 I don’t think so. Your “Bayesian betting, money on the line, gut” tells you it would crash. Doesn’t it. 🙂

Oh…and as far as “conserving wealth” for later. Look at Hotelling’s insight. James knows it. It’s a trivial insight (if you think about it as arbitrage instead of all the complicated math). If you have a depleting resource, price mechanism will naturally compensate you for future scarcity. You don’t have to ration.

And the idea of rationing for future generations is actually very unusual in practice. Most autocrats and politicians, if anything do the opposite! All their incentives are for dealing with the here and now.

A much simpler explanation is that OPEC is interested in the monopolists revenue maximizing price. Right out of the textbook.

Oh….and if you think I’m full of it, look up Hotelling and then check out how the futures curve is backwarded. James needs to address that. It’s a fundamental issue.

Small example, but how relevant is the majors’ capex versus production to the overall industry? Yeah, it’s insight…it’s something. It’s probably even something showing something about the overall problem. I’m not saying don’t cite it…good analysis. But also don’t stop there.

It’s 10% of the industry and with notable differences than NOCs or US LTO independents. Heck, I think some capital in Venezuala or Mexico are severely needed. They have “milked the cow”. Need investment. Shouldn’t you at least discuss countries like that qualitatively? A shrewd analyst would.

P.s. The Kopits state by state charts used to just say ND for recent peaks. Now we have Colorado ( a substantial producer too). It is not out of the realm of possibility that the #1 state, Texas will repeak also. Headed that way. (Would have been crazy talk to TODsters a fw years ago!)

http://media.peakprosperity.com/images/1-OPEC-Crude-Oil-Production%202005-2012.png

Look at what happened in 2008-2009. That was cartel action. Plot the price on there. Look which countries cut production. It’s a smoking gun.

Nony: Please note: (1) the OPEC production decline comes after the price of oil began to decline. It was an effort to keep prices from falling more steeply, it was not the cause of prices increasing in 2007 and 2008. (2) Your graph is the identical data as that shown in Figure 10, Panel A of my paper, except that (a) my graph extends back to Jan 1973 and goes all the way up to March 2014, whereas yours only covers the period Jan 2005 to Feb 2012; and (b) the vertical axis on my graph begins at zero, that on yours does not. The consequence of (a) and (b) is that my way of reporting the data conveys both scale and long-term perspective, which are in fact the issues under discussion here. (3) I acknowledge in the paper that the OPEC cut in 2008-2009 was a deliberate effort to stabilize the price, but nevertheless conclude that other factors account for the quintupling in the price of oil since 2001. (4) You still have not responded to the evidence in Figure 11 of the paper.

James:

1. I agree the 147 was not from the cartel. Was not my point to say every change is from them. Just that they have real impact, so you need to look at them. Much, much more than you do.

I’m aware that the intervention was done in reaction to the price decline. My point is that it was an intervention and did have an impact. Huge one. That is both cartel action and efficacy of cartel action. Smoking gun.

Once, you see that, it calls into question the whole “can’t pump to stop oil prices going up” meme. Doesn’t it? Several years ago, we had the price rise above 40 and the Arabs couldn’t stop it. Then it drops to 40 and they intervene massively to prop up price. I think there was some “don’t throw me in the briar patch, Brer Fox” when that price went up in early 2000s. They are just fine with 100/bbl and intervened to support it when it was coming down (and Hotelling theory would say it should not come down, should not crash…even big temporary demand crashes should be arbitraged to future scarcity and thus hold price up…)

2. That was the best I could find, quick on the net (graphic). I won’t apologize for the timing…since what is in discussion is the 2008 intervention. I agree that we should have a true zero. (But come on, man. That’s not addressing the real micro issues: cartels, Hotelling, etc. Oh…and I got sneered at by your co-blogger when I asked for a true zero graph). In any case, the change from ~40 to ~90 is like a doubling. It sure shows cartel impact on any scale. That’s “market power”, “rational competition” or any other euphemism that my company lawyer tells me to avoid to not get into FTC trouble.

3. I saw that you acknowledged it. It’s just not digging into a big factor. [And I can’t constrain my glee with how that “smoking gun” intervention contradicts your previous white paper’s main point. Funny how you changed it once when price crashed. Then price went up again real fast with the intervention…I guess at that point, you threw up your hands to update your paper every time events moved the evidence. ;)]

4. [Just looking at it.] I agree that figure 11 shows more effort needed to get ME oil. If you look at production/rig count, I bet it’s still lots better than the US. And I bet marginal cost of next barrel is lower (and in a free competition market, it would be equal). I’d also love to see it broken up by country (just for the insight).

P.s. I think it’s a little rich for you to say I ignore your points, when you ignore mine. [Hotelling, Hotelling.] Heck…I even answered the citation question. 🙂

Nony:(1) Monthly OPEC production fell from 33.7 mb/d in July 2008 to 30.4 mb/d in Feb 2009. Over this same period, monthly WTI fell from $133 to $40. OPEC production increased from 30.4 mb/d in Feb 2009 to 31.2 mb/d in Jan 2010, during which WTI increased from $40 to $78. This is your smoking gun?

The only gun I see here is yours, and it is shooting ill-informed blanks in every direction.

(2) No, the best graph you could find was Figure 10 in the paper you came here to sneer at.

(3) You obviously didn’t read the discussion of OPEC, Hotelling, or anything else in this paper, either.

I read them and they were not sufficient. Honest, I have referred to ‘your 2008 white paper’ before. So the idea that I hadn’t seen it is strange.

Yes, it is a smoking gun. They dropped production when price started dropping! 31.2<<33.7. Look at the specific players and how they cut production. That was a clear act of market power. A free competitor does not drop production the way SA, KUW, and UAE did.

Incidentally, in regard to ELM (Export Land Model), could you identify any errors in the following mathematical observations?

Also, as you know I introduced the ELM concept in a brief article in early 2006, focused on the top three net oil exporters at the time (Saudi Arabia, Russia and Norway).

Following is the concluding paragraph from the article (emphasis added):

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/984

Granted, Saudi and Russian production did not turn out exactly as predicted, but Saudi net exports started declining in 2006 (remaining below the 2005 rate for eight straight years), and Russian net exports stopped increasing in 2007 (ranging between 6.9 and 7.2 mbpd since 2007). And as expected, Norway’s net exports continued to decline.

And following is a chart showing the 2002 to 2012 data for the (2005) Top 33 net oil exporters, what I call Global Net Exports of oil (GNE).

In early 2006, we didn’t even have complete 2005 data, but in retrospect, at the rate of increase in GNE from 2002 to 2005 (from 39 mbpd in 2002 to 46 mbpd in 2005), as annual Brent crude oil prices doubled from $25 in 2002 to $55 in 2005, GNE would have been at about 66 mbpd in 2012, versus the actual value of 44 mbpd, as annual Brent crude oil prices doubled again, from $55 in 2005 to $112 in 2012:

http://i1095.photobucket.com/albums/i475/westexas/Slide1_zps3161a25b.jpg

I am now estimating that in only 8 years we have already burned through about one-fourth of the post-2005 global supply of Cumulative Net Exports of oil (CNE). As noted elsewhere, this method of estimating CNE was too optimistic for the Six Country Case History.

James Hamilton in mid 2013:

“But Texas production in 2012 (at 2MM bpd) was still 1.4 mb/d below the state’s peak production in 1970, and I haven’t heard anyone suggest that Texas is ever going to get close again to 1970 levels.”

We’re now at 3MM bpd. Does 3 count as “close” to 3.4??? In any case, if the 2% growth rate continues, it will not just be “close” but pass the record around DEC2014.

And this was not some crazy black swan, James. The trend was well underway for several years. But you talked it down. Maybe a little lack of detachment?

The Texas RRC puts the 1972 Texas (crude oil only) peak at 3.5 mbpd.

The EIA’s estimate for Texas Crude + Condensate (C+C) production for the first four months of 2014 was 2.9 mbpd. The Texas RRC put the Condensate to C+C Ratio at a little over 15% in 2012 and a little less than 15% in 2013, and I think recent data confirm a decline in the ratio, probably as a result of operators shifting to more crude oil prone areas in the Eagle Ford Play. In any case, if we use an estimate of 13% for the current Texas Condensate/(C+C) Ratio, it suggests that Texas crude oil only production in the first four months of 2014 was about 2.5 mbpd, versus 3.5 mbpd in 1972.

Regarding total US C+C production, at a given gross decline rate from existing production, the greater the production, the greater the production decline from existing wells. Of course, the gross underlying US decline rate has probably increased too since 2008.

Let’s assume that the gross underlying US decline rate from existing oil wells was 5%/year in 2008 and 10%/year in 2014. And let’s assume that the 2014 US C+C production averages 8.6 mbpd.

Based on foregoing, in 2008 we lost 250,000 bpd from existing wells (5% of 5.0 mbpd), and in 2014 we would lose 860,000 bpd from existing wells. So, again based on foregoing, a 72% increase in production would correspond to a 344% increase in the volume of oil lost to declining wells–from 250,000 bpd per year to 860,000 bpd per year.

Based on foregoing, in order to hit 9.0 mbpd in 2015, the industry would have to put on line about 1.3 mbpd of C+C new production in 2015.

In other words, the greater the production increase, the closer in time that a region is to the point at which contributions from new wells can no longer offset the declines from existing well, which is why Peaks Happen.

In regard to Texas specifically, I would estimate that the gross underlying decline rate from existing production is at least 15%/year. Let’s assume that Texas crude oil only production averages 2.7 mbpd for 2014*. Based on this estimated decline rate from existing production, Texas would probably have to put on line about 700,000 bpd of new crude oil only production from 2014 to 2015, in order to average 3.0 mbpd (crude only) in 2015. We will see what happens.

*Note that the most recent RRC data show Texas crude only production at about 2.2 mbpd for late 2013 (revised up from 2.1 for the initial estimate). Peak Oil Barrel link to a discussion of recent Texas data:

http://peakoilbarrel.com/texas-rrc-july-oil-gas-report-may-production-numbers/#more-3905

THE RRC data has massive lag and gets adjusted up. You know it. Ron finally knuckled under and conceded that. Blanchard was way off base and has not. Is well documented. Even DCoyne (a peaker, but honest one) has shown it. Use EIA.

As noted above, I used the EIA data (and the RRC Condensate/(C+C) data) get an estimate of about 2.5 mbpd of Texas crude oil production only for the first four months of 2014, versus 3.5 mbpd crude oil only in 1972.

In any case, it’s one of life’s little ironies that the Cornucopians use examples of what are (so far at least) still post-peak crude oil producing regions, i.e., Texas & the Lower 48, to refute the Peak Oil “Theory.”

While it’s entirely possible that Texas and the Lower 48 will exceed the early Seventies peak rates (and I didn’t think it would happen), it hasn’t happened so far, which forces the Cornucopians to argue, in effect, that a reduction in the rate of decline in production, relative to a prior peak, means that we haven’t peaked. And as noted above, the industry faces enormous challenges in trying to indefinitely offset the huge declines in production from existing wells, and I am puzzled as to how anyone can argue against the point that it’s when, not if, that the contributions from new wells can no longer offset the declines from prior wells, i.e. Peaks Happen.

Jeff:

1. The crude versus crude and condensate in 1972 becomes academic because of amounts involved. (Although I believe the intention is to show both.) Here is the best primary report, I could find.

http://books.google.com/books?id=iczXMAAfRmgC&pg=PA53&lpg=PA53&dq=texas+crude+and+condensate+1972&source=bl&ots=rZ91tfujrp&sig=VU2wkCo4rKxSljRYphcMd2I_MF4&hl=en&sa=X&ei=FCbRU-iUGKjjsATFo4GoCw&ved=0CB8Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=texas%20crude%20and%20condensate%201972&f=false

2. Condensate is not exactly WTI, but is still a very high value hydrocarbon which is blended into gasoline. It gets less than WTI but more than heavy sour grades. It’s not the ideal API, but it’s oil. (Associated oil from a gas well, basically.)

3. You have been running around for a long time saying that the growth in Texas is mostly condensate. But Ron’s charts show percentage condensate less than 15% (while total crude and condensate has more than doubled). And that percentage is even dropping lately (since gas wells are getting crushed by the Marcellus). You have not faced how wrong you were on this. But it’s very common for peakers not to admit when wrong.

Here is the RRC link for historical data, which is crude oil only, and as the link states, and as you noted, these are actually preliminary values, so the actual value for Texas crude oil in 1972 was probably slightly greater than 3.5 mbpd:

http://www.rrc.state.tx.us/oil-gas/research-and-statistics/production-data/historical-production-data/crude-oil-production-and-well-counts-since-1935/

In any case, my point was, and is, that you were comparing EIA Crude + Condensate data to Texas RRC crude oil only data, in regard to the 1972 peak rate.

And my point was, if I ad the condensate in, the number is the same. Look at my cite.

Also, you have been running around saying the bulk of new production was condensate when its 15% of a doubled number (and the percentage actually dropping).

Plus, you totally pass by my point about the value of condensate versus heavy sour. and how you can make GASOLINE from condensate.

I can’t make heads nor tails out of the link you posted.

Here are the EIA C+C annual data for Texas, back to 1981:

http://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=pet&s=mcrfptx2&f=a

And here are the RRC crude oil only annual data:

http://www.rrc.state.tx.us/oil-gas/research-and-statistics/production-data/historical-production-data/crude-oil-production-and-well-counts-since-1935/

For 2013, the RRC is currently showing 2013 crude oil production as 2.04 mbpd and condensate production as 0.36 mbpd, for a total C+C of 2.40 mbpd, while the EIA is showing C+C production of 2.56 mbpd for 2013.

In 1981, the EIA showed Texas C+C production at 2.55 mbpd, while the RRC showed crude oil production only as 2.46, a gap of about 90,000 bpd, which is not a big difference. Interestingly enough, the EIA C+C production in 1981 was almost exactly the same as 2013, but the implied Condensate/(C+C) Ratio in 1981 was 3.5% versus the RRC value of 15% for 2013.

I would agree that it’s possible that condensate in 1972 may not have been a significant factor, but if you are arguing that the RRC defined crude oil as Crude + Condensate in 1972, but not in 2013, I think that’s complete nonsense, and in any case I would have to agree with the Professor’s following comment:

In any case, based on the most recent annual RRC data, the RRC is showing 2013 Texas crude oil only at 2.04 mbpd, versus 3.5 mbpd in 1972 (rounded up slightly from 3.45). And if we include condensate, the RRC C+C number for 2013 is 94% of the 2013 EIA C+C number.

Jeff:

I’m saying that if you add the condensate from 1972 to the 3.4, you still have 3.4.

I also discussed how condensate has similar price to heavy sour crude (similar delta versus WTI). It produces transport fuels. Condensate is even called “natural gasoline”. It is an economic substitute (ask James).

heavy, sour = low API oil

WTI/light sweet = medium API

condensate = high API oil

Condensate is associate oil from a gas well. In a similar manner to how associated gas from an oil well happens. Yeah, it’s higher API. Just like associated gas from an oil well is “wetter” gas.

You are really reaching with the attempt to exclude condensate. Heck even the export restrictions call out lease condensate as a form of oil.

Minor correction. The latest RRC data show Texas crude oil only at about 2.1 mbpd in late 2013, versus 2.0 mbpd for the initial estimate.

Nony: The way to establish an error in the statement “I haven’t heard anyone suggest that Texas is ever going to get close again to 1970 levels” (which was made in April 2013, by the way) would be to provide a link to a serious analyst who was predicting in April 2013 that Texas was going to return to the levels of 1970. Here, for example, is the EIA’s assessment from April 2013, which anticipated that total tight oil production from the entire United States would peak at 2.8 mb/d in 2020. And here’s a disucssion of what led the EIA to change its assessment between April 2013 and December 2013.

In my experience, the EIA is very poor at forecasting. Their historical data is invaluable, but their forecasting…is terrible. I suggest you avoid their forecasts whenever possible.

One factor: as an agency of government, they’re handicapped by the need to be very, very conservative. The “reference” forecasts assume no changes at all in policy, which is highly unrealistic. I’m sure you’ve seen the same problem with OMB and CBO forecasts.

James:

1. I agree that you said ‘analysts say’. I think that is fencing a little, though. It’s a caveat on the more negative side [note for instance, you don’t go by the analysts when they predict price drops, so there is some picking and choosing…and by the way, you’ve been right not to go with them on price drops, but not from US geology!] and one that you decided to cite. you study the industry also and had a chance to be more optimistic and insightful and didn’t.

2. You did cover the changed EIA estimate, but not with a ‘this changes what I said before’ slant. ‘Those serious analysts I said were cautioning how small the runup, have changed their minds.’ The slant was more, doesn’t matter anyway since rest of world is making less. (which I actually agree with you on…just wonder why they are making less. Did we simultaneously underestimate US geology and overestimate ROW geology? Or could OPEC have some reserve capacity, they are all so happy not to use?) 😉 But bottom line, I don’t think your coverage was clear enough about correcting your earlier post.

3. I’ve had a little fun now looking at Googled old reports from IEA, EIA, IHS, Bentek, Citi, Woods McKenzie and BP. Basically they all underestimated US production. I wonder why and I wonder what it means? It was not like a hurricane hitting the gulf or a war breaking out. Guess it just means they did not understand the in process change despite all the coverage. (Of course this does imply that further misunderstanding could exist…for example ROW shale development taking off. Also, one can think of the example of the Marcellus and shale gas in general outperforming expectations.) [BTW, the BP report almost nails it…you have to squint and interpolate their chart, but they were the most US shale oil optimistic and come pretty close.] And it’s kind of funny that the crazy, “provocative” reports by Citi and the like ended up being underestimates.

—-

Any way you cut it, when Texas goes over that peak, it is going to be phenomenal and something that you failed to predict.

Nony, it is going to 4 million and even perhaps 5..

Many of Professor Hamilton’s projections are based upon

his personal conviction, that Peak Oil is a matter of time.

Professor,

I believe that the work you do is very good and your conclusions are well thought out, but I am always surprised that you do not give more credit to the theory of Schumpeter. It seems that your approach has two pretty serious flaws. First, you do not consider the political intervention that prevents the production of the factors of energy production and second, you never seem to give credit to the amazing technology that has reduced use of the factors while actually increasing the reliance on energy production. You seem to follow the all too common backward looking economics. Economics should not be practiced while looking into a rearview mirror.

This is a good paper to read to review basic concepts.

http://web.mit.edu/ceepr/www/publications/workingpapers/98008.pdf

And I’m not saying that there is anything “new” or spectacular in it. No way!

And I know James knows this stuff…and probably all kind of super hard Diff E Q’s, all kinds of concepts and papers I’ve never even heard of. But the point is…when you want to understand something, look at it in terms of supply and demand. Micro, micro, micro.

That an economics educator, heck one with a popularizer bent does not try to get his audience to think in terms of supply and demand just bugs me. I mean look at Kopits with the “supply constrained” versus “demand constrained”. Has he ever make a PQ curve and looked at the lines for both supply and demand? Built it up with little blocks (segments)?

Yes, I have, Nony. Year by year. What do you want to know?

Good job (serious). Those rectangle charts are a good way to fly. Forces you to think and disaggregate. Reflects supply and demand. Micro econ.

Nony: Not think in terms of supply and demand? I don’t know which amazes me more, your complete ignorance of everything you say, or the extreme confidence with which you express your opinions.

Please read these papers [1], [2]. And then please apologize for the nonsense you’ve been trying to spread here.

Professor:

I had seen those before (well the white paper one, other one is similar). My point is really buttressed by you citing those two papers.

1. They’re both BEFORE the smoking gun EFFECTIVE cartel intervention. I mean the event came afterwards and HURT your two papers.

2. (I think this is a macro versus micro thing). The only supply and demand curves, you show are a literal “X” crossed lines. A cartoon. And then we have a bunch of price time series in your figures. (Do you endorse the crazy triangle of doom or can I please at least get you to speak out against that…that awful influence of flawed thinking propagating in your comments section.)

You need to have curves with shape, with segments. Look at these curves (ones with rectangles). That gives insight to see the height and width of the rectangles.

https://www.google.com/search?q=cost+curve+commodity&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ei=K0LRU-SPEcr0oASJtIKIAg&ved=0CAYQ_AUoAQ&biw=1920&bih=911

Same thing applies with demand. You need to (at least) look at the different market segments.

Here’s what Nony says: “The only supply and demand curves, you show are a literal “X” crossed lines. A cartoon.” And here’s what the paper he claims to be describing says: “The initial price P₀ is then determined by the transversality condition that if the price P_{t} follows the dynamic path given by (7) from that starting point, the cumulative production converges to the total recoverable stock as t→∞.”

And by the way, the Adelman analysis that you are holding up as superior generated the most spectacularly inaccurate prediction of what was going to happen in the years after they were written of anything I know in the literature.

I’m not holding out Adelman as having made a particular good prediction. I think it is the macro prof in you who wants to make predictions. I’m holding that paper out as a good paper to just understand the levers and to think micro economically about the industry.

You absolutely DO have crossed straight line X cartoon figure as your supply-demand figure in both of your papers. I am not saying that you think this is the exact picture of the industry. I’m saying you don’t even bother to try to construct real supply and demand curves with little rectangles, like a good trade study of a commodity chemical would have. That’s my point.

” I don’t know which amazes me more, your complete ignorance of everything you say, or the extreme confidence with which you express your opinions.”

You can combine the two. My skipper back when I did spec ops called it the “balls to brains ratio”. He actually wanted it pretty high.

P.s. Slow down with the rebuttals. I’m Googling away to find that one analyst report from pre-April 2013 that you missed. 😉

I love the put down Nony.

The condescending tone reminds me of the popular, widespread condescending tone towards west coast aboriginals. The loudest tend to be vigorous supporters of open access resource allocation policies.

Or put in common terms. The most condescending tend to have a “what was yours is now mine” attitude.

So what’s your angle? Cheap energy?

Tom It’s about big power plants burning natural gas because of the far lower price of natural gas and the economy of scale of big plants.

I don’t think that really addresses my point. I said that I did not see any obvious reason why electric vehicles could not be charged from decentralized sources rather than centralized sources. I don’t doubt that generating power from natural gas burning plants has to be centralized, but not all power has to come from natural gas burning plants. I also wouldn’t be surprised that wind power has to be centralized as well because only a (surprisingly few) spots have steady and reliable wind. But I’m not convinced that centralizing solar power makes sense unless you’re in love with meters. In fact, what I’ve read says that solar only makes sense as a decentralized power source. So why not recharge your electric car using the solar panel on your roof? Or here’s a novel thought; as solar panels become lighter and less expensive, why not make the roof of your car a small solar panel that juices up your car while it’s sitting in the parking lot when you’re at work? The point is that charging your car isn’t like demanding baseload energy to run your air conditioner. It’s more like running your washing machine; you can do it more or less when you want.

JDH My conclusion is that hundred-dollar oil is here to stay.

I’m confused. Your conclusion doesn’t seem to follow from all of the very good arguments and facts that you presented. Your conclusion seems too optimistic. Doesn’t your argument really suggest that $100/barrel oil is likely to be a temporary low that we will not ever see again once global demand picks up? So I don’t think $100/barrel oil is here to stay; sounds more like it’s making a brief pit stop at $100 before moving on.

2slugbaits: I am assuming that tight oil production will continue to increase over the next several years, so that the situation since 2011 (over which the price has been fairly stable) is similar to what we might expect for the next several years. Libya (situation can only improve), Iraq (situation unclear) and China (ditto) are important wildcards.

Slug: You’re having a Roseanne Roseannadanna moment. I never said anything about centralized charging. That would indeed be silly. I said “centrally burning natural gas and using electric power as a distribution medium.”

Nick says “Of course, the US could easily cut it’s oil consumption in half with efficiency – that’s far cheaper than $100 oil.”

Nick says ” If wind, solar and nuclear aren’t practical, why is our biggest competitor, China, building more of all of them than us or anyone else?” (minus the massive state credits to manufactures)

Could you please provide supporting evidenced for these questionable statements?

Of course you will not because you make all of this up as you go alone.

Hans,

if you check energy consumed per unit GDP then you have a relatively poor performance in the case of the USA. Or, if you take primary energy consumption, final energy consumption, oil consumption per capita then these numbers are much much higher in the USA than in most other developed economies. What is your problem?

Therefore, improving the efficiency to levels is indeed a posssible alternative to increasing oil production.

China adds 2013 and 2014 more wind capacity than any other country. As most of the NPPs under construction, which are not already zombies, are in the PRC, the most likely result is that China proviidess most of the new nuclear capacity. In case of PV the situation is a little bit unclear, but China will be in any cases at least one of the top three.

Correction:

“Therefore, improving the efficiency to levels is indeed a posssible alternative to increasing oil production.”

should have been

Therefore, improving the efficiency to levels of other developed countries is indeed a posssible alternative to an increasing production of expensive oil

Spielgel, your points are all valid..I would add, that as prices have

increased so has the degree of efficiency..If we had EuroLand type

of pricing, America would be even more efficient in the use of gasoline.

Nevertheless, America could not reduce goo consumption by 50%

without entering a depression…Nick G, statement about that was

entirely without any and all merit..

“Therefore, improving the efficiency to levels is indeed a posssible alternative to increasing oil production.”

Not likely..You would need a declining use of the product or population in order to achieve those goals;

both of which may not be healthy to the economy.

Any Bird Shredder requires a million or two in subsidy in order to

be built; hardly a accreditation to efficiency…They are also noise polluters

as well..

..If we had EuroLand type of pricing, America would be even more efficient in the use of gasoline. Nevertheless, America could not reduce goo consumption by 50% without entering a depression.

Europeans use only 18% as fuel per capita for personal transportation, so they would think that 50% of our level of consumption was way too much.

Now, it would be very inconvenient to reduce fuel consumption that much overnight (though it could be done – the average vehicle only carries 1.2 people, so just doubling that would do it – carpooling, the horror!), but it would be easy over, say, 10 years.

Nick G, we are not EuroLand nor are we the Congo; which

has even a higher efficiency use of petrol.

we are not EuroLand

What do you mean? Europe doesn’t have a reasonably comparable economy?

please provide supporting evidenced

I thought the arguments were obvious: we see this kind of information every day, if we’re at all tuned into energy news.

Think about vehicle efficiency: it’s doubled over the last 40 years. That’s due to improved engineering. The US consumes about 140 billion gallons of gasoline every year – that improved efficiency will save about $5 trillion over 10 years (assuming, of course, that gasoline wouldn’t rise to $200 per barrel, if the US were to consume twice as much oil for passenger transportation). How much did that engineering cost? Perhaps $10 or $20 billion in engineering salaries and improved Computer-Aided-Design? That’s about 500:1 return on investment.

So, the average US car gets about 22MPG (2.9T VMT divided by 140B gallons). As we’ve seen with the newest cars and hybrids, it’s relatively easy to double that efficiency. The engineering to do so might cost another $20B (actually, most of the work has already been done), while we’d save about $2.5T over 10 years. You can quibble with these numbers a little, but the overall result is overwhelming: investment in improved vehicle design has infinitely better ROI than drilling in the Arctic.

So, why don’t consumers demand better MPG? Mostly because consumers have a lot more on their minds: they have a wide range of requirements for their vehicles, and MPG is only one of them. And, fuel cost is a relatively small component of the overall cost of vehicle ownership (it’s easy to find this kind of infor. For instance, a little Googling for an analysis of driving costs will find http://publicaffairsresources.aaa.biz/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Your-Driving-Costs-2014.pdf).

The same is true for China’s investments in wind, solar and nuclear. For instance, put “china wind power building” into google, and you’ll get ” the development of wind energy in China, in terms of scale and rhythm, is absolutely unparalleled in the world.” from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wind_power_in_China

Nick G, there is the Law of Diminishing Returns…

The ICE vehicle can and will only become so efficient

until until either a new form of propelling or radical

mandates.

Moreover, the consumer must accept and buy in order

for these high MPG to succeed…Good ideas are not always

successful in the markets.

I would add, that I seriously doubt that auto manufactures

have a better ROI than the goo industry.

there is the Law of Diminishing Returns

The average US vehicle only gets 22MPG. A Prius gets 50MPG. A Volt gets 220MPG (counting only gas). A Leaf gets infinite MPG.

The ICE vehicle can and will only become so efficient until until either a new form of propelling

It’s here, it works, and it’s better. A Tesla, for instance, is better and cheaper than the comparably priced competition.

I seriously doubt that auto manufactures have a better ROI than the goo industry.

Why, specifically?

the consumer must accept and buy in order for these high MPG to succeed

US pure EV sales have doubled each year for the last three years (from a very small base) and pure EV and PHEV sales are growing faster than hybrid sales did when they were introduced . Tesla has a large backorder book. Nonetheless, PHEV sales aren’t growing as quickly as many people had hoped.

Cost isn’t the problem.

Hybrids, EREVs and EVs are already the low cost choice for Total Cost of Ownership (per Edmunds.com), so if cost were the driver….we would have reached the tipping point. Buyers of new light duty vehicles (cars, pickups, SUVs) sales just don’t seem to be very price sensitive. The minimum cost US vehicle is about $11k, while the average vehicle is more than $30k. The average new car gets about 25MPG, while 55-100MPG vehicles are available. New car buyers just aren’t paying much attention to minimizing costs.

Supply isn’t the problem: Toyota, Nissan, Ford and GM will tell you that they could double production of their hybrids, EREVs and EVs literally overnight, if demand were there.

There are two big problems:

First, the vast majority of people are very slow to move to new things. Individual consumers have to see people around them using this new thing for quite a while to become comfortable with them. For example, online food ordering has overwhelming benefits for parents, but Webvan went bankrupt: they counted on people moving to a new thing too quickly.

Commercial users of heavy duty vehicles face large problems of economy of scale, long-lived investments and operating in a tough competitive market. Large fleet customers have been experimenting with pilot programs, but have been afraid of being first movers (“Pioneers are the ones with arrows in their backs”). That suggests that the early rate of adoption may be deceptive. At a certain tipping point fleet buyers will decide high oil prices are permanent, and that electrified/alt fuel vehicles are clearly cost justified. Then, sales will grow quickly.

Second, the primary reason for EVs is external costs like Climate Change and the cost of military conflict in the M.E., and as a society we haven’t prioritized dealing with those costs. We just haven’t. Until we do, with things like carbon and fuel taxes (which even the most conservative economists support for external costs) and acceptance by Republicans, it’s unrealistic to expect fast movement by consumers.

Nick G, currently, the Prius is in the upper end of fuel

economy…Doubling it, will be very difficult and would

require numerous technical advances.

I would also add, that the payback period, for the extra costs

of owning a Prius is somewhere between six to nine years…

Many Americans can not afford to own it, as the average feet

age is now nearly 12 years.

The Tesla S, is an excellent vehicle, if you can pay the $80,ooo

or more…Like the Prius, it will never enter the mainstream, unless

costs decline.

EV sales only account about 1% of the new sale auto market.

I can not agree with Edmunds, as upfront cost on Hybrids and EV

are substantial to that of a ICE vehicles…In fact, the replacement of

the Prius battery pack will exceed $4,ooo; a very expensive after market

repair.

“New car buyers just aren’t paying much attention to minimizing costs.”

Indeed, they are, by leasing and having mortgage length loans.

“First, the vast majority of people are very slow to move to new things.”

I believe Americans are rather quick to adopt..If you could sell a Telsa for

$25,ooo bucks, it would become the number one selling vehicle.

“Second, the primary reason for EVs is external costs like Climate Change and the cost of military conflict in the M.E., and as a society we haven’t prioritized dealing with those costs.”