U.S. stock prices fell more than 5% in the two-day aftermath of the British vote to leave the European Union. But equities have since regained those losses and are back near all-time highs.

S&P 500 stock price index, Jan 4 to July 1. Source: FRED.

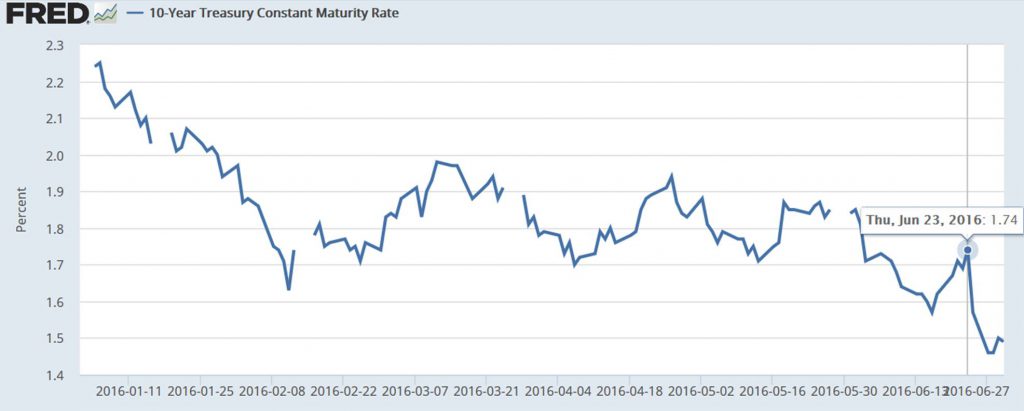

By contrast, the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds fell about 25 basis points post Brexit and stayed there. That puts long-term interest rates down about 75 basis points for the year and near their all-time low.

Yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury bond, Jan 4 to June 30. Source: FRED.

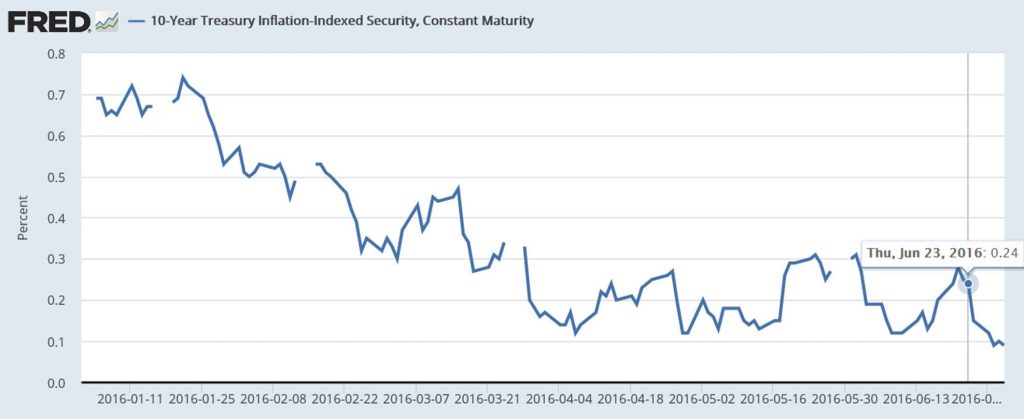

The inflation-compensated 10-year yield fell about 15 basis points post Brexit and 60 bp for the year. That leaves the other 10-bp decline in nominals post Brexit to be accounted for by lower expectations of inflation.

Yield on 10-year Treasury Inflation Protected securities, Jan 4 to June 30. Source: FRED.

All this is consistent with the view that Brexit initially sparked fears of substantial effects on economic growth. These fears may have since subsided. But the expectation remains that central banks around the world will be keeping real rates low for an even longer period than anticipated prior to the British vote.

Here’s a plot of the 10-year expected inflation rate that is implied by the difference between the previous two graphs. Currently it’s down to 1.4%. If you described this series as “well-anchored,” what you might mean is that it’s anchored well below the Fed’s long-run 2% target. And it seems to have drifted even lower as a result of events in Britain last week.

Breakeven inflation rate on 10-year Treasuries, Jan 4 to June 30. Source: FRED.

In other words, markets think the Fed will try a little harder, but be a little less successful, to achieve its long-run objectives.

JDH> All this is consistent with the view that Brexit initially sparked fears of substantial effects on economic growth.

Here I assume you are referring to US economic growth and not UK growth, right? Barkley Rosser points out that while the FTSE-100 has largely recovered (as Krugman shows), other broader indices, such as the FTSE-250, that are less trade oriented have not recovered.

But it’s clear that interest rates and inflation ain’t coming back to historically normal levels anytime soon. Helicopter money needed now.

But, But NAIRU Says Hyper-Inflation is Right Around the Corner!

And don’t forget the Taylor Rule, not to mention our $20 trillion debt that the Peterson Institute has been warning us about forever. We need to balance the budget and cut Social Security now, now, now!

All good points.

Except NAIRU doesn’t seem to really work anymore. If it did, inflation would have taken off a while ago. I think workforce participation rate (25-54) is the reason.

The 10 year yield tells us something very simple and profound: supply of and demand for loanable funds is terribly lopsided, indicating (at least) a medium term expectation of low growth. The Brexit induced decline in the 10 year yield tells us expected growth has declined.

See Bernanke’s blog for criticisms on the Taylor Rule:

http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/ben-bernanke/posts/2015/04/28-taylor-rule-monetary-policy.

One might think that, with yields declining, stock PE ratios might increase (Dow Theory). But I submit that once 10 year rates go below 4%, the inverse relationship breaks down and the PE ration can’t go much above 25. Where is the PE currently? From multpl.com, it is at 24.3.

We are stuck.

There are many factors driving the stock market. Some investors bailed-out and some bought, (there’s been cash on the sidelines), there’s rebalancing and hedging (TLT – 20+ year Treasury bond ETF reached an all-time high), buying of stocks with relatively higher dividend yields (compared to bonds), end-of-quarter window dressing and expected new money at beginning of quarter put to work on the pullback, bullish holiday bias, anticipation of earnings announcements in July, a slower Fed tightening cycle and slower economic growth, etc.. Is this greater volatility in a trading range or a new trend over the next few months?

From the point of view of the UK, the big question is if the government implements Brexit at all. It has to trigger article 50 to do so and both the main candidates in the Tory leadership race have said they will put this off until the new year.

So the immediate effect of Brexit is mainly uncertainty hitting the construction sector. This may trigger a recession, but more direct results will depend on when or if they trigger the actual exit.

All of the candidates in the Tory leadership race insist they will, but that means nothing, they have to, as in the final stage of the election process they are voted for by the very Euro sceptic Tory rank and file.

One intriguing possibility is that they will establish a Brexit “department” or “working group” to establish the basis for triggering Article 50, while of course, the French and the Germans refuse to discuss the details until the article is triggered. If that isn’t a recipe for a very slow process, then what is?

I think the effects are nearly all in political and in Britain, so far. The real effect of Brexit is political turmoil. Brexit was won by red-brown cooperation on nativism and isolationism, with the Tory right wing and UKIP leading and Corbyn passively supporting with coded speeches that damned the EU with faint praise. But this was intended by both to be only a one-time cooperation, and neither the Tory right wing nor Corbyn are able to put together a functioning ruling coalition or win a general election. So the ad hoc answer to this seems to be shaping up of a sort of Tory right lite led by May that’s so far promising to go through with Brexit but not in a hurry and obviously reluctantly, since she was pro-remain. That’s really why markets calmed down – because May is more or less credible and we’re not getting the totally unpredictably shambolic option of Johnson or total political paralysis. Interest rates are down partly because growth expectations have weakened and partly because central bank policy expectations have shifted towards loosening, but even in the UK there’s no longer the fear of imminent recession that was evident in the first days after the vote.

In the US there’s been a clear departure from the plans for tightening later this year. Before Brexit there were the bad employment numbers. But those may both have been partly just convenient excuses when the real issue is concern how the US will fare if the global economy continues to soften and as the boost from the lowering of oil prices runs out (ie the delta fades into the past). On one hand most of the FOMC seems keen to “lift off,” it seems to largely to prove wrong those who’ve been arguing ZIRP is a trap. On the other hand most are doves, so it doesn’t take so much to dissuade them from tightening.

7/11 – From the financial markets after a week, Brexit appears to be “much ado about nothing.”