Is borrowing short and lending long a risky strategy for the Fed?

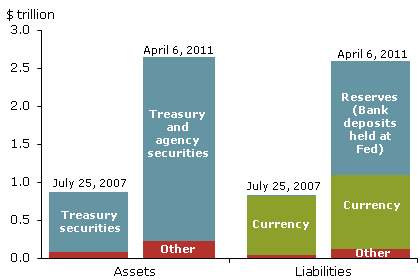

The Federal Reserve today is holding $1.4 trillion in U.S. Treasury securities, which is $600 billion more than it held four years ago. The maturity of those securities has also increased significantly. In April 2007, more than half of those securities were one year or shorter. Today, the fraction is down to 8%.

|

Since 2007, the Fed has also acquired $132 billion in debt from Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the Federal Home Loan Bank, and $937 billion in mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by Fannie, Freddie, or Ginnie Mae. Where did the Fed get the money to buy all this stuff?

The answer is, whenever somebody sold these items to the Fed, the Fed credited an account that the seller’s bank maintains with the Fed in the form of new Federal Reserve deposits. At the moment, most of those new reserves are just sitting there at the end of each day on some bank’s balance sheet. Reserve balances with Federal Reserve banks have gone from $9 billion in April 2007 to almost $1.5 trillion today.

The Fed is currently paying banks 0.25% interest on those reserves, and is collecting an average interest rate of 4% on its long-term securities. That netted the Fed a healthy profit of $80 billion in 2010, which it returned to the U.S. Treasury. In effect, the Fed is borrowing short and lending long, making a huge profit on the difference, and handing it back to the Treasury.

But of course, that only works in your favor when the short rate is below the long rate. At the moment, the short rate is well below the long rate, and historically that has been the average relation. But if short rates rise, is the Fed exposed to a loss on its portfolio?

|

A recent article by Glenn Rudebusch of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco notes that the risk is substantially less than the simple “borrow short, lend long” interpretation might suggest. The reason is that $1 trillion of the Fed’s liabilities take the form of currency in circulation, which you can think of as funds the Fed has permanently “borrowed” at 0% interest. Rudebusch calculates that the interest rate on reserves would have to rise to 7% in order for the Fed not to earn a positive cash flow on its current portfolio, once you factor in the benefit to the Fed from the fact that a good fraction of its liabilities require no interest payments.

Rudebusch’s conclusion is that if the Fed’s holdings of MBS and longer-term Treasuries are providing a beneficial economic stimulus, fears of interest rate risk to the Fed’s portfolio are not a good reason to alter the course.

What about to the treasury?

The cash flow difference on interest rates is a red herring. They have a huge margin of safety there.

The real issue is mark-to-market losses on their long-duration assets if rates rise. And if the Fed responds that they don’t have to mark to market because they will hold to maturity, isn’t that an admission that they can’t shrink their balance sheet if they need to?

The Fed has no risk. The trearsury, of course, does. With rates low, the treasury by borrowing short is risking a rate rise by an independent fed which will increase the financing costs. On the other hand, the long term bonds will look sweet with low rates and a huge inflationary increase in rates. If that is the plan the treasury should increase its duration.

Also a kind of incomplete distinction between currency and reserves, since I would bet that some of the reserves are actually currency at the Fed rather than line items on some ledger? And if so that currency still gets interest from the fed. Whether the currency has been printed or not, but not yet withdrawn by the bank, should not matter. The absolute obligation of the fed is to print the currency underlying the reserves. Thats why they are paying banks to keep them there.

“Is borrowing short and lending long a risky strategy for the Fed?”

No, but please answer the question:

“Is the Fed’s borrowing short and lending long a risky strategy for the Treasury?”

I’ll buy this:

“Rudebusch calculates that the interest rate on reserves would have to rise to 7% in order for the Fed not to earn a positive cash flow on its current portfolio”

So what would happen to the US federal budget deficit if new debt issues came in at 7%? Can the answer be anything not including the word disaster?

OT

Platts on OPEC output

The latest batch of estimates of OPEC production, including OPEC’s own, show that the cartel did not cover the drop in Libyan production in March.

The IEA shows Libyan production falling by 940,000 b/d month-on-month to 450,000 b/d and total OPEC output falling by 880,000 b/d. The EIA puts Libyan production at 300,000 b/d, 1.04 million b/d lower than February levels, and OPEC output at 28.72 million b/d, 1.27 million b/d down from February.

Platts’ latest survey of OPEC and oil industry officials and analysts estimates that Libyan output dropped by 930,000 b/d to 460,000 b/d in March and that total OPEC output fell by 630,000 b/d to 29.17 million b/d.

OPEC itself, using secondary source estimates, puts March output at 29.12 million b/d, representing a drop of nearly 627,000 b/d from February, with Libyan production down nearly 990,000 b/d at 366,000 b/d.

Saudi Arabia’s March output is pegged at 8.9 million b/d by the IEA, 8.961 million b/d by OPEC, 9 million b/d by Platts and 9.1 million b/d by the EIA.

All of which begs the question: What are the conditions Saudi Arabia and OPEC see as the justification for the sort of output increase that will at least cover the entire loss of Libyan production?

OPEC has insisted that the high prices currently prevailing on world oil markets–earlier this week, North Sea Brent traded at a new 32-month high of $127.02/barrel–have more to do with speculative activity than with fundamentals of supply and demand.

“In terms of fundamentals, the recent events alone do not justify the current high price levels. Instead, these represent a sharp increase in the risk premium, reflecting fears of a shortage in the market in the coming quarters,” OPEC’s Vienna secretariat says in its latest monthly report.

OPEC members, the report says, “have accommodated most of the shortfall in [Libyan] production, ensuring that the market is well supplied.”

But if OPEC considered markets to be fairly balanced when Libyan supply was running at normal levels of close to 1.6 million b/d earlier this year, are they still balanced now that Libyan crude exports are virtually nil?

http://www.platts.com/weblog/oilblog/2011/04/13/should_opec_pum.html

I think this fairly expresses my sentiments on the matter.

So long as we don’t have an aggressive energy policy, we set the stage for this kind of dynamic.

Erm what? You dont get what the interest rate risk is.

The interest rate risk is that the Fed bought at X and has to sell at X-5 because when it comes to unwind its portfolio rates are higher (and so bond prices are lower).

The fact that they are funding these instruments at positive carry (interest income > interest cost) is not the point under discussion when people talk about the fed’s interest rate risk. People are talking about the loss ont he market value of the bonds when the Fed sells them as part of the operation unwind.

Jim, finally you have understood that the Fed has forced the banks to finance the government. Once you consolidate the Treasury and the Fed, you will see that the banks –through what is accounted as bank reserves– have been financing the Treasury. This is the reason why it doesn’t make any sense to use the aggregate called monetary base (currency + bank reserves at the Fed) for monetary analysis. If you want to analyze the prospect of high inflation, you should focus only on currency. If you want to analyze the financing of the Treasury’s deficit, you cannot ignore the banks.

Because of my 50-year experience with central banking I can tell you that central banks often use “bank reserves with the central bank” as an accounting trick to mobilize funds that are used to finance government spending (as has been the case of Argentina many times but not today) or to manage the solvency of the banking system (as has been the case of China since 1995).

Indeed, in your country the flow of bank credit to the Treasury since September 2008 has improved the banks’ balance sheets, at least because bank reserves are not counted as risky assets. Please make clear that what the Fed has earned and paid back to the Treasury is the interest the Treasury paid to the Fed. What you’re asking is whether the banks will continue financing the Treasury at a low interest rate or their cost of funding the Treasury will increase. Although market forces will likely increase their cost of funding the Treasury, the Fed and the Treasury now have enough power to limit the interest paid to banks. This is a first step in building a state banking system.

The fed is nothing but a GSE. If you consolidate the fed with the treasury you see that the government is shortening the maturity of the federal debt and subsidizing the banking system by paying an above market interest rate on reserves. So what? Well, financing the government with short-term debt narrows the window in which the government can respond to a run on the dollar. Does this matter? Maybe.

“Please make clear that what the Fed has earned and paid back to the Treasury is the interest the Treasury paid to the Fed.”

Precisely, Mr. Barandiaran.

http://imperialeconomics.blogspot.com/2011/01/qe1-2-bank-loans-money-supply-and-debt.html

Also note the virtual 1:1 correspondence to Fed fiat digital debt-money printing to credit banks’ balance sheets as reflected by banks’ cash assets and incremental holdings of Treasury and agency paper since QE began.

Moreover, M2 less the incremental effects of gov’t borrowing and spending is below 2% annualized YTD. With private employment growth of 0.7% and M2 at ~1.7% growth, the private US economy cannot grow with price inflation of 2.5% or faster. CPI is already reported at growth of ~2.2% yoy and at 3- and 6-mth. annualized rates of nearly 6% and 4%, implying that annualized real private M2 and GDP are at increasing risk of decelerating to 0% and contraction as early as this qtr. to summer.

The Fed’s net QE effect has been to liquefy approximately ~10% of current banks’ total assets, a portion of which was in the form of banks’ purchases of new Treasury issuances.

The notion that the Fed’s QE was intended to stimulate the economy is just silly; rather, it was to liquefy banks’ balance sheets, a process that is far from complete.

If the capitalist banking system precedent of the 1830s-40s, 1890s, 1930s-40s, and Japan since the ’90s repeats, as seems likely, we will see the monetary base converge with the level of bank loans over time, whereas banks’ non-loan assets will converge with the monetary base and bank loans before the debt-deflationary regime runs its course sometime later in the decade.

Bank loan/deposit growth from the early ’80s reached the critical differential rate of growth of an order of exponential magnitude, i.e., Jubilee tipping point, to GDP and wages coincident with the onset of global peak oil production in ’05-’08, which mathematically requires bank loans to contract at least 30% over time, i.e., debt-money or asset deflation.

Consequently, the Fed, banks, insurers, and pensions will be the largest holders of US debt BY FAR. IOW, we will owe to ourselves in US dollars most of the outstanding debt we issued to bail the banking system and fall in receipts, as with Japan today, not to the Chinese, Japanese, Brits, and Saudis.

The US gov’t will borrow an equivalent of 100% of private GDP today before the debt-deflationary process runs its course, and a growing share of gov’t funding will come from liquidation of corporate equity, bonds, and real estate.

Finally, it is assumed that the Fed has extraordinary influence, or control, over US economic activity and price inflation. Wrong. The emerging structural effects of Peak Oil, population overshoot, and unsustainable growth of China-Asia demand for oil and other commodities (thanks in large part to US firms’ investment and production in Asia) is causing a lower US$ and pass-through effects to US and global business inputs, which will squeeze profit margins and real consumer spending per capita. The Fed is largely powerless to do anything about the effects of these larger global resource constraints.

This situation is not unlike what happened during the 1890s to WW I and 1930s during the peak and decline of the British imperial trade and sterling reserve regime which culminated in the collapse of “globalization” of that era and the end of sterling as the reserve currency and the devaluation of sterling in 1931.

Only this time the Anglo-American global trade regime is coming to an end with the primary global energy source, crude oil, at an inflation-adjusted price of 10 times that of the late 19th century to the first quarter to half of the 20th century.

“Please make clear that what the Fed has earned and paid back to the Treasury is the interest the Treasury paid to the Fed.”

I really like this statement. It exposes a lot of nonsense in discussions of whether the Fed is “making a profit,” or whether it is ripping taxpayers off to pay banks or other creditors. However, right now, the statement is just a bit off. Much of the interest earned by the Fed is from non-Treasury debt. What aggravates me is that the Fed would be able to hide a substantial loss on these assets by returning to Treasury less than what the Treasury gave the Fed.

Right now, the Fed seems to be making a real profit for the Treasury, but I think that is in part because they are not properly accounting for bad debt they have taken on and that taxpayers will eventually be forced to bear. It is in that sense, too, that the issue is not the Fed’s cash-flow, but the true accounting of the net gain or loss on their purchases of non-Treasury debt. And when I say “Treasury,” I’m speaking of the public purse as it should be, without the federal government’s explicit guarantee of the GSE debt. With that guarantee, of course, any loss on these assets owing to bad debts that are not repaid would belong to the Treasury in any event, whether or not they were bought by the Fed.

Why is everyone talking about the Fed selling off assets? It can pay interest on reserves now, and it’s been examining whether it has the ability to offer what would be essentially Fed CD’s.

If there are issues that would prevent the Fed from selling these bonds, then it can rely more heavily on these other facilities.

Finally, even if the Fed does suffer a loss or even dip into negative equity, on the consolidated Federal balance sheet, the Fed is a blip. Treasury can cover that blip trivially.

This is a non-issue.

ndk,

I think the issue is that those excess reserves can be traded in for currency at the will of the banks….

James,

I don’t understand why you are posing such a question when you know better than anyone else that the Fed controls whether it pays interest on excess reserves or not. So in effect, it entirely controls the ‘borrowing’ side of the equation. Better yet, it doesn’t matter if the Fed makes a profit or not — the Fed’s POMOs are just mechanisms to control money supply. What am I missing?

Mike: The Fed does not intend to let the reserves it has created end up as currency in circulation. It will therefore be forced to either raise the interest rate paid on reserves (to persuade banks to continue to hold on to excess reserves) or else sell some of its assets. The interest rate it needs to set for this purpose will be dictated by the demand for excess reserves rather than something the Fed can freely choose on its own.

“The Fed does not intend to let the reserves it has created end up as currency in circulation. It will therefore be forced to either raise the interest rate paid on reserves (to persuade banks to continue to hold on to excess reserves) or else sell some of its assets. The interest rate it needs to set for this purpose will be dictated by the demand for excess reserves rather than something the Fed can freely choose on its own.”

Hopeless fiction! The FED subsidized the money center banks by absorbing their impaired mortgage securities for a price well in excess of real value. The price the investment banks agreed to pay for this largess, was to support the US equity markets but contain credit creation (growth of M2).

US banks acknowledge that the higher capital requirements of Basil 3 necessitate capital accumulation. Since the fat cats don’t want to be diluted by stock issuance, they’re having the FED and Treasury provide them interest payments on their “excess” reserves in order to accumulate capital. This is in contrast to European banks who have to sell new stock.

The FED and Treasury have a huge amount of power. If a money center bank decides to sell loans against its “excess reserves”, the FED could just as easily take back the reserves by laying the mortgage paper back on the bank. Or, the government could pursue fraud charges against the bank and its executives. Or, the FED could raise capital requirements, instantly eliminating the “excess” in the reserves.

Arguments about “demand” for “excess reserves” is deception. Stop the euphemism. Call it what it really is: Government subsidy of racketeering.

again, it is likely wrong to conclude that the bank reserves are ‘just sitting there,’ esp. when the focus is on the overall level of bank reserves (roughly $1.5 T). Those reserves can be lent/borrowed in the Fed Funds market and while reserves may transfer from one bank to another the overall level of reserves (roughly $1.5 T) will remain the same. And w/n each reserve/borrow of reserves there is the possibility for the banks to combine the reserve flow with securities lending and repo deals feeding stock and commodity speculation.

Further, w/n the last two weeks a new dynamic appears in the Fed’s balance sheet. During that time $80 bn of reserves have been converted (probably via data entry just like they use for QE purchases which are paid for via data entry enhancing bank reserves) into the Treasury’s checking account at the Fed. Perhaps this is a data entry slight of hand to provide spending money for the treasury facing debt limit restrictions.

Just as the bank reserves were data punched into existence, now said reserves are being transferred to the Treasury via typing.