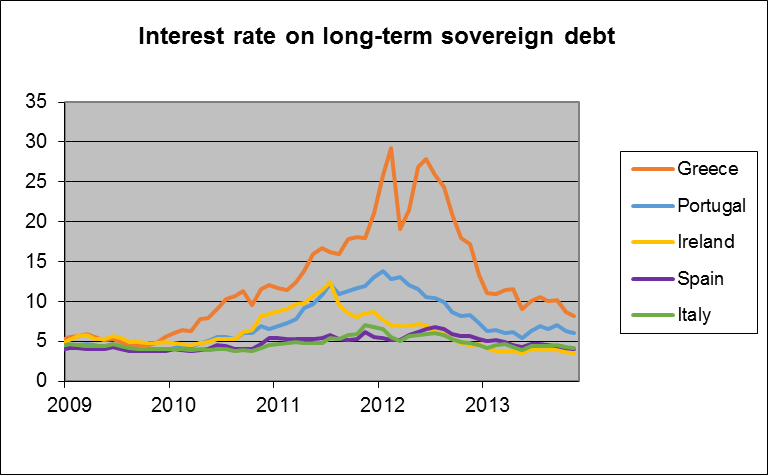

After a wild ride in 2011-2012, interest rates have settled down on European sovereign debt. For now.

|

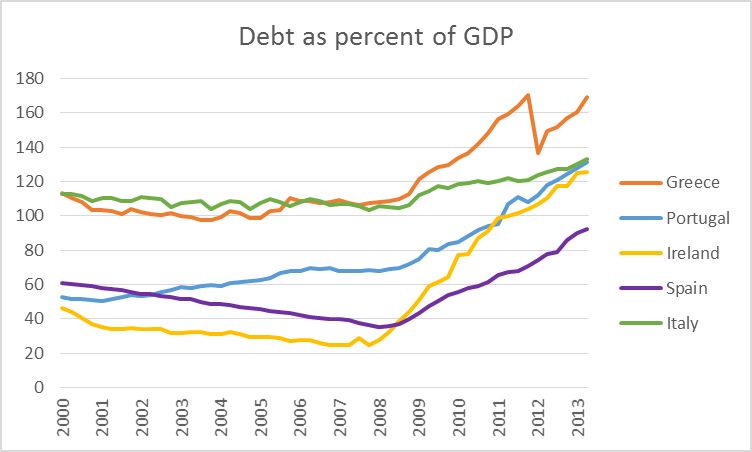

Greek yields fell sharply following the PSI agreement in March 2012, a de facto default that ended up reducing the value of Greek’s debt by 20%. But as a result of ongoing deficits and plunging GDP, the ratio of debt to GDP for Greece is now almost back up to where it was in at the end of 2011. In the mean time, debt/GDP has continued its uninterrupted climb for Portugal, Ireland, Italy, and Spain.

|

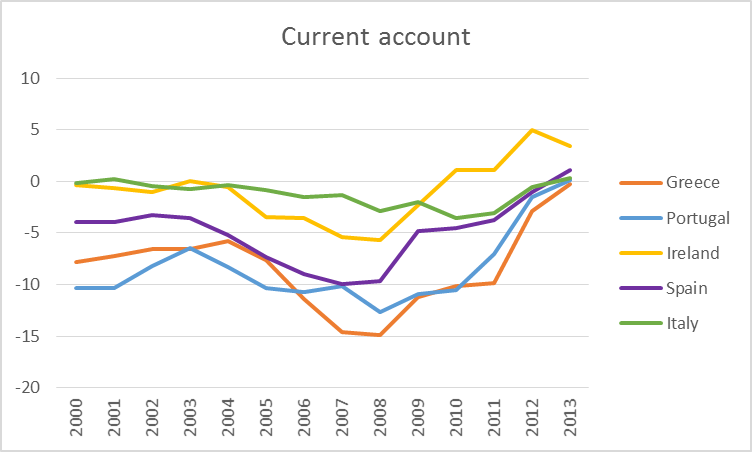

On the other hand, these countries have seen sharp improvements in their current account, having gone in a very short period from large deficits to outright surpluses. Unfortunately, this seems not so much due to currency depreciation or wage and price adjustments restoring competitiveness as it has to the collapse in aggregate spending (on both home and foreign goods) associated with the sharp economic downturns in these countries.

|

Still, the improved current accounts mean less borrowing from abroad and reduced vulnerability to shifting moods of international credit markets. My recent paper with Greenlaw, Hooper, and Mishkin (and much previous research before us) identified the debt-to-GDP ratio and current-account deficits as two key factors that influence a country’s vulnerability to sudden spikes in borrowing cost. One distinctive feature we found in the data was a strong nonlinear interaction between the current-account deficit and debt loads. Our paper used a 5-year average of the current-account/GDP ratio as the variable that interacts with the current debt load to predict the interest rate on a country’s long-term sovereign debt. I was curious to see what our estimates would imply if we assumed that the recent improvements in the current account turn out to be permanent.

The table below summarizes how debt, the current-account surplus, and interest rate on government debt have changed since 2012 for these 5 European countries. The final column gives the amount by which the 10-year yield on government debt would be predicted to fall if debt/GDP changed by the amount indicated in columns (2) and (3) and the change in the current-account surplus given in columns (4) and (5) is assumed to be permanent. Much of the observed drop in yields could be explained by the elimination of big current-account deficits.

| debt/GDP | current-account/GDP | interest rate | actual | predicted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2013:Q2 | 2007-2011 | 2013 (proj) | 2012 | Nov 2013 | change | change | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Greece | 170.6 | 169.1 | -12.1 | -0.3 | 22.9 | 8.2 | 14.7 | 11.2 |

| Portugal | 108.0 | 131.4 | -10.2 | 0.1 | 11.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 4.2 |

| Ireland | 106.5 | 125.7 | -2.2 | 3.4 | 6.0 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 1.8 |

| Spain | 69.1 | 92.3 | -6.5 | 1.1 | 5.9 | 4.1 | 1.8 | 1.1 |

| Italy | 120.8 | 133.3 | -2.5 | 0.3 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 1.4 | 0.9 |

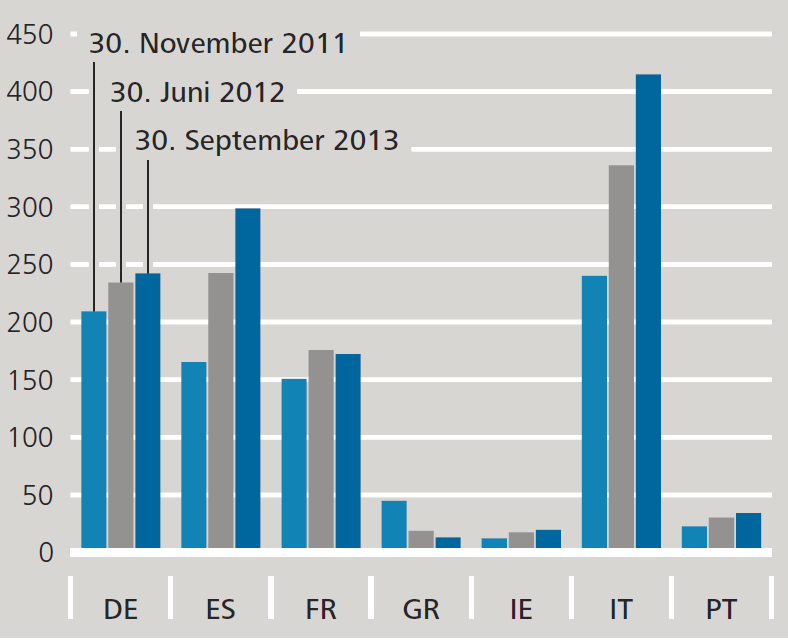

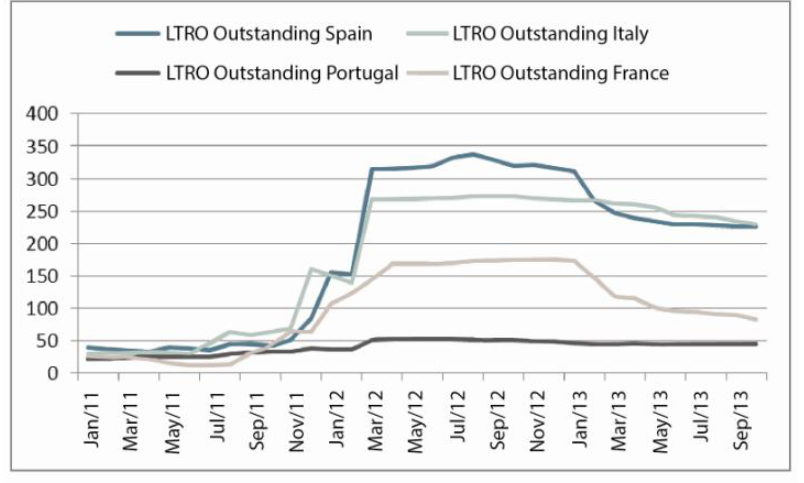

An improving current-account balance means less borrowing from abroad. So who is funding the growing sovereign debt? The answer appears to be domestic banks. The Telegraph’s Ambrose Evans-Pritchard leads us to page 33 of this

report from the German central bank which reports that Spanish monetary financial institutions increased their holdings of Spanish government debt by € 134 billion between November 2011 and September 2013. That’s an 81% increase and accounts for 65% of the total increase in Spanish sovereign debt over the period. Italian banks increased their holdings by € 175 billion, a 73% increase which accounts for more than 100% of the increase in Italian sovereign debt.

|

And where did the banks get the funds to lend to the government? From the ECB, whose outstanding loans to Spanish and Italian banks come close to half a trillion euros.

|

This is a fine deal for the banks, borrowing from the ECB at a lower rate than they can earn on the sovereign debt. But it does not change the underlying reality. Greece’s debt load of 170% of GDP and interest rate in excess of 8% means that its taxpayers must surrender 14% of the country’s total income every year just to make interest payments on the debt. Portugal needs to sacrifice 8% every year. Neither is going to happen; further defaults seem unavoidable.

But if the ECB does not keep renewing the LTRO loans, rates would spike back up and we’d replay last year’s excitement in financial markets.

This can will be kicked down the road.

Thank you. Such a pretty picture:

1. After years of spending cuts, Greek debt/GDP ratio has not improved.

2. Other austerity cases like Portugal, etc. have seen that ratio get worse without any period of improvement. (We could add the UK debt ratio hasn’t improved either.)

3. Improvement in current account is due to a dearth of money in the economy to be spent on stuff. In other words, increasing poverty reduces imports.

4. The debt ratio is being propped up in an unsustainable manner by local sources. That last was really interesting.

This describes a near total failure of the Euro – unless one deems the ECB’s actions as a reasonable substitute for a central taxing/spending authority (which I don’t). It describes a total failure of austerity, which it appears has only managed to make things worse in most of these countries.

This is a great analysis, Jim.

Aren’t we seeing just the opposite of austerity, Jonathan?

Periphery government spending is sustained, if I read Jim correctly, by massive LTRO loans from the ECB to periphery banks.

In the absence of these loans, we’d see much greater austerity.

As for domestic austerity, if a country uses the Euro as currency, then it cannot control either its fiscal or monetary policy. The Greeks cannot manufacture Euros. Nor can they source them locally, except with very high interest rates. Nor can they raise taxes, which are austerity by definition.

Thus, if you are talking about reducing austerity, as a practical matter you are suggesting that the Germans should make outright grants in the hundreds of billions of Euros range indefinitely to the periphery countries. I think this is hard to conceive.

Alternatively, you could be calling more much higher inflation, 5-10%, in the Eurozone. I think there’s a theoretical case to be made for this, but I question whether it’s politically viable in Germany, for example.

Thus, if you want to end austerity, then you’re really left with Depart, Devalue and Default. My read from Jim’s post is that this may still be on the table.

Good AP article on the global retirement crisis:

http://hosted.ap.org/dynamic/stories/U/US_GREAT_RESET_RETIREMENT?SITE=AP&SECTION=HOME&TEMPLATE=DEFAULT

It’s interesting to read this article, and then plug in assumptions about constrained global net exports of oil.

Two final thoughts, Jim:

If the loans to the periphery are channeled through domestic banks, and we assume the sovereign will default, then the domestic lending banks will also default.

What then? Will the ECB end up owning the entire southern tier banking sector? Or will the ECB sell its share to the northern tier banks, which end up owning the southern tier banking system? Is all this a prelude to a modern day colonization of the south by the north?

Also, could we have a separate update post on Ireland, please?

Just have to load up the ECB with debt until inflation is the only alternative. Progress to this goal is being made but will be long in coming.

Steven Kopits: I am optimistic on Ireland, since I see the country’s problems as a one-shot deal that are now behind them. But I am not sure how the situation in other countries will play out.

Stephen, you confuse government borrowing levels with spending and you seem to confuse another point I thought was clear – and which the post covered – that lower economic activity produces less revenue so the debt ratio can go up as you cut spending. You could look this up in a matter of minutes. I thought the post was clear about this, particularly in reference to the current account. I really don’t know what else to say.

For example, Greek Real GDP has shrunk year after year. (Nominal GDP is at 2005’s nominal levels.) There are gobs of facts easily accessible about this kind of thing for all these countries.

I have a small comment about Ireland: I think we tend to attribute something extra to Ireland because it is close to so many Americans (and they speak English!). I think that means we tend to believe more in stuff like their tech sector because we can more viscerally understand it than a similar tech sector in a less familiar place. As a longtime reader of the Irish press, I have doubts about the economy’s ability to do much for a long time. And they’ve trapped themselves in a tax regime that encourages companies to use them for tax status without doing much good for employment and local wealth. If they change that, the business – in some certainly not all cases – would be tempted to leave. I sometimes think companies have resisted investing more in Ireland because they don’t want to be trapped there if the tax treatment changes. But that’s one issue out of many.

I’d rather write that Ireland kicked the can down the road. The debt swap, where the promissory notes were exchanged for long term bonds, was hidden monetary financing and against the EU rules.

Not that they had any choice though.

Now future generations will bear the burden and hopefully inflation will relief it.

Who is going to pay back the debt — the unemployed?

Perhaps a bit more on Ireland.

Ireland’s government has always had an intimate relationship with high finance. Huge tax advantages and the 12,5 % corporate tax rate have been the carrot ON the stick and government made a firm commitment to it as they reserved austerity for the lesser gods.

Moreover how did this influence Fairfax (took a stake in the Bank of Ireland in 2011) and Templeton (bought a lot of bonds in 2011)?

Unemployment drops as the lesser gods move to other sanctuaries – http://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/er/pme/populationandmigrationestimatesapril2013/#.UsEIk_ZfOHQ.

An export-led econonmy it has always been and will remain to be so (finance, insurance, pharma … double Irish).

Maybe that is the right road:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rkRIbUT6u7Q

AK-47s Fired On German Ambassador’s Home In Athens

http://www.morningjournal.com/general-news/20131230/shots-fired-outside-german-ambassadors-home-in-greece

The reason I ask, Jim, is that Ireland’s debt-to-GDP ratio still appears to be rising per the second graph above. Is that right? And if so, why?

Jonathan –

If you are against austerity, normally that means you prefer either i) lower taxes, or ii) higher spending. Financing either of these requires greater debt if a country is in a currency union, as is Greece. Thus, increasing debt is the only way to ease austerity. But perhaps you have some other policy in mind?

The way to get out of this trap is to Depart, Devalue and Default. That’s not cost free, either, but I think it would be better than the depression now gripping the southern tier economies.

JDH wrote:

“…these countries have seen sharp improvements in their current account, having gone in a very short period from large deficits to outright surpluses. Unfortunately, this seems not so much due to currency depreciation or wage and price adjustments restoring competitiveness as it has to the collapse in aggregate spending (on both home and foreign goods) associated with the sharp economic downturns in these countries.”

Good analysis Professor. I especially thank you for the quote above. But this is not an exception but the rule. A current account deficit means a country is wealthy enough to import. When a country has economic trouble it cannot afford to import. The balance of payments is an indicator of financial health and any attempts to artificially change the balance only distorts and harms an economy.

It aappears that the bottomline of your analysis is that it is the same old same old.

JDH This is a good post. I’d like to extend it in two ways. Question: Causality from sovereign debt to bank purchases of sovereign debt to ECB purchases from banks. A daisy chain. Would you care to comment on the final link of the chain not mentioned? Federal Reserve to ECB. How many billions have US taxpayers put up to float the ECB? Or might it approach a trillion? Question: As you have learned something about the connection between current account deficits and a central government’s debt ratio, has the light bulb yet come on for you regarding free trade?

Very nice analysis and an excellent point about the likelihood of further defaults down the road. But I was particularly struck by your point that the present situation is a very good deal for the local banks who are making quite a good return on the spread between what they are borrowing from the ECB and what they are lending to their own governments. In essence, the local banks are being recapitalized through this mechanism.

One possible endgame is that the local banks will become sufficiently strong so that they can survive another round of defaults. Perhaps this is wishful thinking, but right now the local banks are doing quite well.

jonathon,

How did print and spend expansionary policies workout for the US debt to GDP? Thanks in advance.

Tell you want, let me help you:

“The U.S. national debt is now about 73% of gross domestic product, the Congressional Budget Office said Tuesday. The percentage of debt is higher than any point since around World War II, and twice the percentage it was at the end of 2007,”

First off there is no “austerity” anywhere in Europe except perhaps Hungary, Greece, Portugal, Iceland, Lithuania and Latvia. Some of these countries are doing better and some are still struggling. Therefore we have to conclude there is more that affects this than just spending.

Also, we must break “austierity” into austerity by higher taxes and austerity by lower spending. If you pull the numbers from eurostat you will find that the countries that cut spending and were modest about raising taxes did the best. You can throw Greece right out the window because if they don’t improve their business environment, they will never grow. As of 2012 they were ranked 85th in the world by the world bank as far as a business climate. For comparison, that puts them a solid 35 countries behind Khazakstan.

In short, you can never spend your way out of a debt problem and you can’t cut your way out of a debt problem if you have strangled your country with regulations, corruption, unions, and cronyism.

‘Unfortunately, this seems not so much due to currency depreciation or wage and price adjustments restoring competitiveness as it has to the collapse in aggregate spending (on both home and foreign goods) associated with the sharp economic downturns in these countries.’

A bit offhand for someone who is usually careful with the data.

From Bruegel blog 15 November 2013,you can see that except for Greece, by far the major source of the CA improvements over the past 5 years has been expansion of exports rather than compression of imports.

http://www.bruegel.org/nc/blog/detail/article/1195-balance-of-trade-adjustment-in-the-euro-area/

Jeffrey,

If you read the pension article carefully, you’ll see that 65 year olds are living about 5 years longer (the article doesn’t mention that another important factor is that more people are managing to live to age 65), while getting pensions under control requires raising the retirement age by 3-4 years.

So, people are living longer, and they have to work 2/3 of that additional lifespan. Doesn’t seem too bad to me.

I am pretty sure, that your analysis is completely wrong, taking consequences of political decisions as cause of developments in the financial markets, instead of understanding all of this as consequences of political will.

Your calculations of interest paid by various nations have nothing to do with reality, but for that you would have to know about european reality.

A more detailed and referenced response will come in the new year

Nick G,

I think that the biggest problem with expectations of general retirement is the following chart, showing total global public debt versus the GNE/CNI Ratio* for 2002 to 2012:

http://i1095.photobucket.com/albums/i475/westexas/Slide2_zps01758231.jpg

We have seen a 10 year increase in total global public debt versus a 10 year decline in the percentage of Global Net Exports (GNE) that are available to importers other than China & India.

As have discussed, the $64 Trillion question is what happens in the next 10 years, but in my opinion global debt and equity markets are not accurately pricing in what I believe is likely to be a continued long term decline in Available Net Exports (ANE), i.e., the volume of GNE available to importers other than China & India. And of course, China & India are not the only developing regions that have shown a strong increase in oil consumption.

In any case, what the foregoing chart shows is that the total global public debt in 2005 was about $660,000 per bpd of ANE and in 2012 total global public debt was about $1,370,000 per bpd of ANE. This is a double digit annual rate of increase in total global public debt per bpd of net oil exports available to importers other than China & India.

*GNE = Combined net exports of oil from (2005) Top 33 net oil exporters, total petroleum liquids + other liquids, EIA

CNI= Chindia’s Net Imports

Solid piece. I think yields were brought down by the ECB’s OMT policy, which amounts to a promise to bail out national sovereign bond markets if and when yields spike. Closing the current account deficits surely helps keep them down. But without the OMT promise, the commercial banks would be under pressure and wouldn’t be able to fund sovereigns. That’s what was happening at the peak of the crisis, and the OMT announcement calmed it down.

On a technical note, it’s actually the southern European national central banks that have funded the southern European commercial banks which have in turn funded the sovereigns. The ECBs role was to permit that by repeatedly relaxing standards. The ECB after all is run collectively by the NCB chairmen.

On the “blame austerity” meme, the question is what was the alternative? For northern governments to spend big on bailouts, until they get voted out and then you suddenly need austerity squared? For southern governments to quit the euro and deeply devalue (isn’t that just another kind of austerity?). The reality is the south has been given as much aid as was politically possible to allow them to have as little austerity as possible. That has alleviated some pain but also dragged out the adjustment, which still is only partial. The Balts who took the full hit of austerity straight off will be better off in the long run, that’s already abundantly clear.

I find the post a bit frightening. The ECB is forced to redistribute funds from northern to southern banks, because southern residents are depositing their money in northern banks. This would drain the southern countries of money without the reverse flow. Southern residents fear their country may default and leave the euro. Either the southern residents have unreasonable fears, or their banks are being stupid. Meanwhile, TBTF U.S. banks are borrowing at zero interest rates here to lend to the southern sovereigns, making a nice profit on the interest spread and helping push up the euro. Nice money as long as none of the loans goes sour and the euro does not start to fall. Note that sovereign debt was exempted from the proprietary trading restrictions on banks. We might yet find out if U.S. taxpayers are the bottomless pit that many have assumed they are.

Happy New Year to all on these boards.

Jeffrey,

The argument isn’t about whether oil exports to countries other than India & China are dropping, the argument is what that means.

The PIIGS countries are generally much more dependent on oil imports than other countries. What does that tell us? Dependence on oil imports is bad for one’s economic health (for example, India is drowning in debt due to fuel subsidies).

There are cheaper and better alternatives to oil: we need to transition to them ASAP. The countries that do so will be more successful economically.

@ James Hamilton

I promised you a response in the new year, and here it is:

1. Your central error is that you assume market interest rates as a proxy for what a Euro country actually has to pay.

Nothing can be further from the truth.

Germany pays 2.62% average coupon on its federal debt (http://www.bundesbank.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/Service/Bundeswertpapiere/Rendite/kurse_renditen_bundeswertpapiere_2013_12_excel.xlsx?__blob=publicationFile)

Greece pays a 2.0% coupon on its outstanding government debt to private holders(e.g. ISIN GR0138014809, redeemable in 2042) after the PSI conversion, and a slightly lower rate to its substantial debt to the Euro Institutions, basically just inflation compensation.

The US has to pay 3.93% (ticker symbol ^TYX) on a newly issued 30-yr bond, for comparison, Germany 2.74% on the mere 2 billion of 30 year bonds we added in 2013 (ISIN DE0001135481 increased from 14 to 16 billion)

2. your second massive error is, to assume, that any Euro member would be exposed to financial dynamics, based on its own numbers alone.

The Euro currency bloc runs a 250 billion $ yearly current account surplus (basically Germany), which would be available to fend off any potential aggressor against one of its members, e.g. via OMT, which has not been used so far, and I don’t expect it.

It is just like NATO article 5, an attack on one of us is an attack on all of us.

OMT would come only with “strict conditionality”. Any buying of sovereign debt is based on a turn-around plan, approved by the ESM, on which the German parliament has full veto power.

When Soros broke the Bank of England (BoE) in 1992, it was standing alone.

As long as Euro countries stick with their financial targets, as laid down in treaties (stability pact), they have safe shelter under the wings of the German Eagle, and no Soros, Paulson, or any other speculator can touch them.

That makes your whole paper a futile exercise, I am afraid to say.

Happy New Year.

genauer: You could describe PSI either as a lower interest rate on a fixed face value of outstanding debt (as you are doing) or as a legislated decline in the market value of outstanding debt (as the calculations above have done).

The question for sustainability is the marginal interest rate paid on newly issued debt. The government only raises funds through borrowing by the amount of the euros delivered by buyers of the bonds when newly issued. If your claim is that those bonds (like the ones in the past) will in fact not end up delivering the promised interest rates to the borrowers, then you and I are in agreement. The word that I use for such an event is “default.”

JDH,

the PSI was a credit event (“default”), no doubt,

declared by ISDA, http://www2.isda.org/greek-sovereign-cds/ on 9th March 2012,

and the auction result on 19th March was with 21.5% pretty low.

But it is pretty unlikely that this would happen again, because it would be very stupid to default on debt, on which they pay 1 – 2 b per year interest, and making Europe very, very mad, which provides 4 and in the future more like 6 – 8 b in net balance payments.

Ireland and Spain have already exited their support programs, with 10-yr interest rates at 3.4 and 4.1%, compared to the US 3% harldy at any crisis level. Net payments after inflation of about 2 – 3% GDP in the future are absolutely feasible, together with some 1 -2 % in real debt reduction per year.

Ordnungspolitik at work.

Portugal is determined to exit in a year as well, 10-yr rates have come down this year from 8 to 5.9%

The problem child Greece will probably take some more labor, but

“There will be no Staatsbankrott in Greece”, the old and new German finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, has spoken. He represents the political will of 80% of the vote in Germany. As long as we see reasonable efforts, they can borrow through the ESM close to German rates.

Where does this factor into the equations of American economists?

Since the numbers for the official loans to Greece are now out in the open

http://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/krise-in-griechenland-euro-krisenmanager-regling-widerspricht-athen-a-942029.html

1.5% interest on 30-year loans, no interest in the first 10 years,

makes for a NPV of 0.45, using the US 30-year rate of 3.9%

but it is not enough for them, and they demand all sorts of constitutional crimes .

What will happen when Europes patiences finally runs out?

Sorry, I forgot to put my name into the field

Since the numbers for the official loans to Greece are now out in the open

http://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/krise-in-griechenland-euro-krisenmanager-regling-widerspricht-athen-a-942029.html

1.5% interest on 30-year loans, no interest in the first 10 years,

makes for a NPV of 0.45, using the US 30-year rate of 3.9%

but it is not enough for them, and they demand all sorts of constitutional crimes .

What will happen when Europes patiences finally runs out?