A growing number of observers are starting to conclude that we’re never going to see the rebound in growth rates that many people had anticipated as the U.S. recovers from the Great Recession. Here I comment on a new paper in which Northwestern Professor Robert Gordon explains the basis for his pessimism.

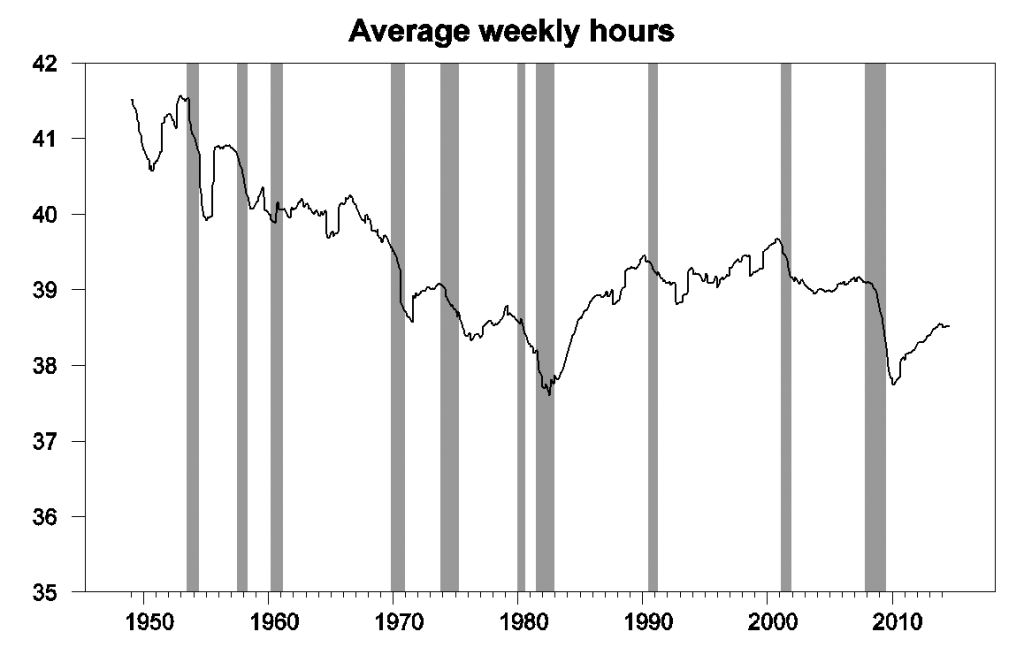

A streamlined version of Gordon’s analysis would decompose the growth rate of output as the sum of growth in productivity (output per hour worked), growth in average hours worked per employee, and growth of number of people working. We received a temporary boost to growth from the second factor as a result of a cyclical rebound in the average workweek since 2010. There might be a further modest contribution from this source if hours per worker get all the way back to their average value over 1988-2008. But more than half of any boost we might hope to see has already been realized at this point.

12-month average values for hours per worker, 1949:M1-2014:M8. Data source: BLS.

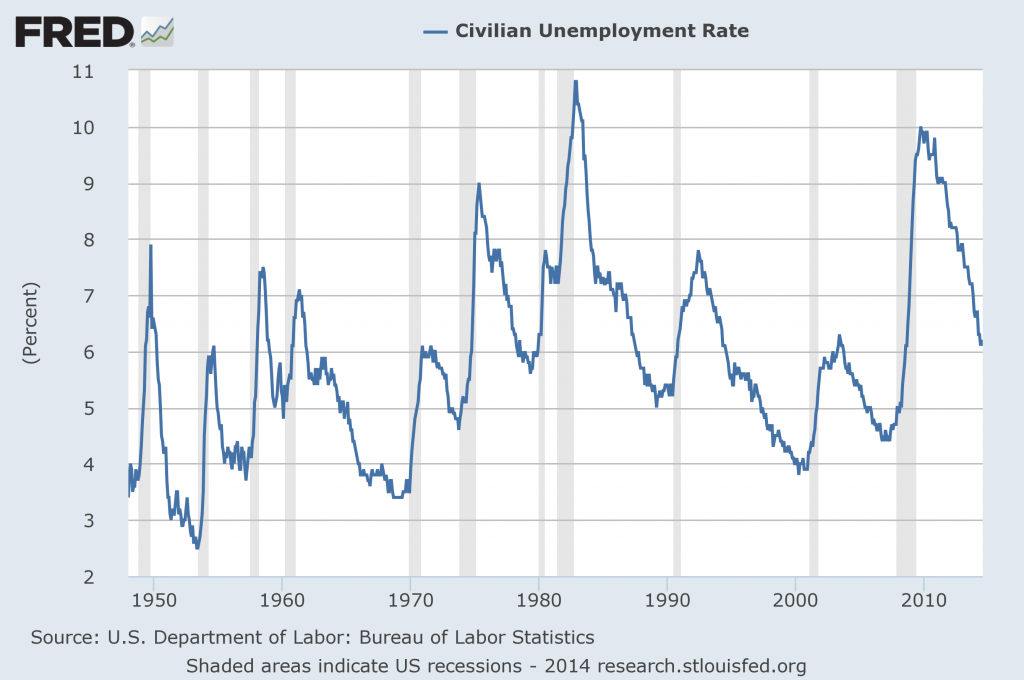

We also have enjoyed a temporary boost in growth from the third term, an increase in the number of people working, as a result of the declining unemployment rate. But with the unemployment rate already back down to 6.1%, it again seems unlikely that further drops in the unemployment rate can make a major contribution to future U.S. growth rates.

Source: FRED.

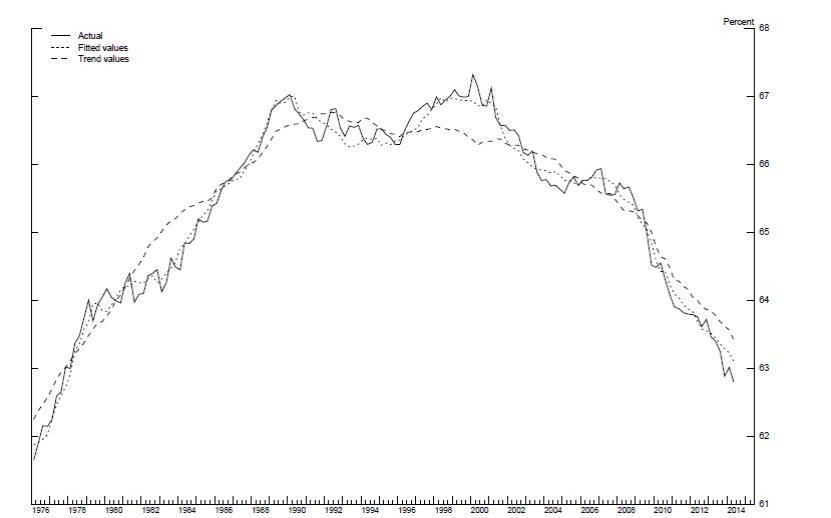

An alternative source of rising total employment would be a recovery in the labor force participation rate. But the decline in this began well before the Great Recession, and seems largely due to demographic factors that are unlikely to be reversed.

Labor force participation rate (solid) and estimated trend component (dashed). Source: Aaronson, et. al. (2014).

Thus a key factor in any prediction of faster U.S. GDP growth would seem to be based on an improvement in productivity.

Gordon writes:

Forecasters universally predict that actual real GDP growth will increase from the 2.1 percent average of the past five years to between 3.0 and 3.5 percent per year over the next two to three years. For output to grow at that rate without a decline in the unemployment rate to four or even three percent would require some combination of a much slower rate of decline in the labor-force participation rate or even a reversal toward an increasing LFPR, as well as a revival of labor productivity growth well above the 1.2 percent average growth rate of the past decade, not to mention the 0.6 percent average over the past four years.

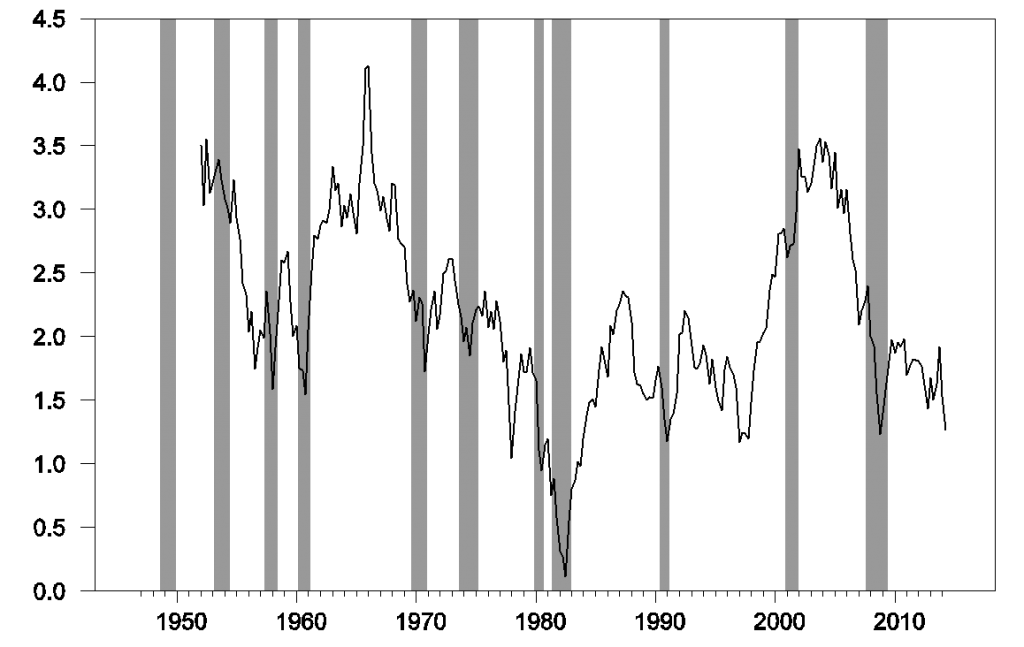

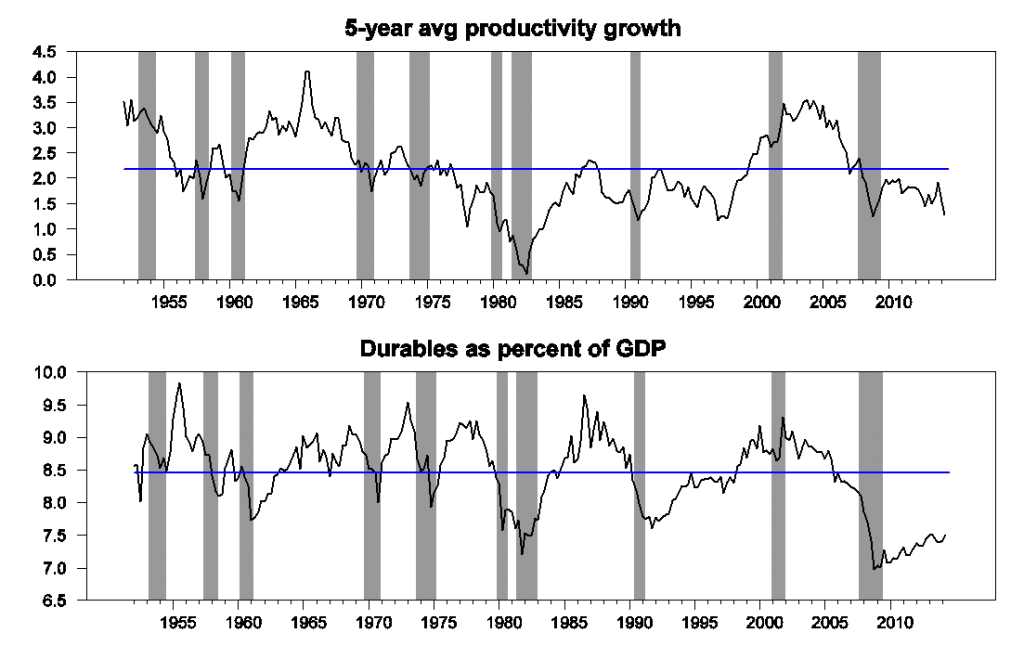

Economists usually think of long-run productivity growth as primarily determined by technological innovation and capital improvements. But cyclical factors also have an effect on productivity that extends much longer than some might suppose. The graph below plots the average growth in U.S. productivity over 5-year intervals ending at each indicated date. It’s pretty clear that these intermediate-run averages are very strongly affected by the decline in productivity associated with economic recessions and the rebound in productivity usually associated with recoveries.

Average annual growth rate of nonfarm business sector real output per worked over 5-year periods ending at indicated dates, 1952:Q1-2014:Q2. Data source: FRED.

A boost in aggregate demand can lead to higher productivity for reasons of simple accounting. Suppose you are operating a retail store and have the same number of employees today as yesterday. If more customers show up to buy today, your measured productivity (how much you sell divided by the number of hours your employees put in) is necessarily going to increase. If the demand stays high, you might find it necessary to hire more workers to meet the higher volume. But since many tasks (such as security, cleaning, and maintenance) won’t double when sales double, there will still be a gain in measured productivity when demand goes up. Something similar is true for many manufacturing facilities that have significant underutilized capacity.

The strong relation in the data between measured productivity and the strength of demand can be seen by plotting productivity together with other strongly cyclical series such as purchases of consumer durables. When consumers are trying to reduce spending, big-ticket items take the brunt of the cutbacks, and when confidence finally returns, purchases of consumer durables make up an unusually high fraction of total spending. Periods when productivity is growing slower than average correlate pretty strongly with episodes when consumer durables make up a smaller fraction of total spending than average. Durable purchases remain depressed today, and that may be a factor in continuing weak productivity numbers.

Top panel: productivity growth. Bottom panel: spending on consumer durables as a percentage of GDP. Horizontal lines represent historical averages.

To be sure, many economists interpret the causation as running in the opposite direction. They argue that if technological improvements have been particularly favorable (so that productivity growth has been strong), consumers may become more optimistic about the future, and therefore devote a higher fraction of their budgets to big-ticket items. But to me, the natural interpretation of the correlation is the traditional Keynesian one that I described above as resulting from the direct effect of higher spending on measured productivity.

For this reason, I am a bit more optimistic than Gordon. At least as far as the next several years are concerned, I side with those who expect above-average growth as consumers’ and firms’ finances continue to recover. But Gordon makes the interesting and I think correct observation that some of the U.S. economic growth since 2010 has already come as a result of factors such as a lengthening workweek and falling unemployment rate, developments that by their nature cannot be projected to continue for much longer. I agree with Gordon that the U.S. should expect a slower growth rate of potential output over the next decade than we saw in most of the twentieth century. But that doesn’t mean that we still couldn’t see better growth numbers for 2014:Q2-2015:Q4 than we’ve experienced on average over the last five years.

Gordon’s pessimism is wholly warranted and demonstrable:

Per capita aggregate of real labor productivity and prime working age population, civilian employment per capita, and real non-residential investment per private employment per capita:

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/fredgraph.png?g=KgE

Total gov’t spending (including transfers), household health care spending, and household debt service as a share of disposable income, summed as a share of GDP:

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/fredgraph.png?g=KgH

With total gov’t, health care, and debt service at over 50% equivalent of GDP, the US economy cannot grow unless there is growth of gov’t (attributable to war, food stamps, and unemployment payments in recent years), illness, and household indebtedness. However, given the sahre of GDP, growth of these sectors create a drag on the rest of the private sector. Therefore, the rest of the private sector outside financial services and health care cannot grow.

Then add Peak Oil and the associated drag effects of oil consumption to final sales at the current recessionary level, and oil consumption to final sales and gov’t, health care, and debt service to GDP precludes growth of real final sales per capita indefinitely.

Gordon is correct, albeit for more and different reasons than he cites.

But the US is not alone, as similar conditions exist in Japan, the EZ, and eventually Canada, the UK, Australia, and China, as structural drag effects from excessive debt to wages and GDP, demographics, and fiscal “austerity” preclude post-2007 growth of real final sales per capita indefinitely.

Peak Oil, population overshoot, and global resource depletion per capita ensures that “Limits to Growth” and the end of growth per capita have arrived. Hereafter, that growth per capita is no longer possible, i.e., a steady-state regime is becoming entrained in the developed world, the imperative will be redistribution and related economic, social, and political innovation to avoid collapse of the oil-, auto-, debt-, and suburban housing-based economic model of COLOSSAL waste perceived as “wealth” (what Herman Daly refers to as “illth”).

Perpetual growth of human population, resource consumption per capita, and debt on a finite spherical planet were never plausible objectives (as Soddy, Daly, Fuller, and Boulding correctly argued), and now we are witnessing the evidence to prove it.

Impact of Peak Oil has largely been been negated due to advancement in technology that enabled shale discoveries, deep water drilling, marginal oil field development cleaner coal technology on the supply side and development of more fuel efficient vehicles on the demand side.

Some economists are saying that older workers aren’t leaving the work force and are working longer to recoup losses in their homes and retirement funds (AARP polls show this); and these same economists are saying older workers aren’t leaving the work force to make room for younger people fresh out of high school or college (creating more “churn” in the labor market).

But at the same time, there are other economists (and some of the same) who are saying that the decline in the labor force is because of an “aging work force” — even though the first Baby Boomer retired (EARLY) at the age of 62 in 2008 — yet the long decline in the labor force participation rate began in April of 2000.

We have 1 million a year retiring on Social Security and 3 million a year graduating from high school (wanna-be prime-age workers).

Why not just say that the “job creators” aren’t creating enough jobs because their profits are already at record highs and they see no need to repatriate profits from overseas or reinvest them (or risk them) here at home. There have been doing “more with less” and will continue to offshore, downsize, automate and robotize whenever they can.

The first electric car was just made with a 3-D printer. How long will it be before all human labor is obsolete? When will the job creators start being taxed to pay all the displaced people a Basic Income?

More here…

http://bud-meyers.blogspot.com/2014/09/older-workers-retirees-disabled-boomers.html

Seen through the lens of capital assets, it seems expectable that productivity could be low for an extended period.

We know we have underinvested in infrastructure of all types for an extended period, so we are not now benefiting from the yield on that investment. Further, our response to the crisis allowed cash flows to capital assets of all types to diminish, likely accelerating their abandonment. This should have caused a direct reduction in aggregate yield due to those abandoned investments. And we have a narrow definition of capital assets, where for instance we do not include public spending on education as capital investment, yet it is abundantly clear that such investment has significant yield, just as any other capital asset does. So when we reduce that spending or shift it to finance that mortgages the spending, we should expect decreased yield there, too.

At this point, were we to fiscally fill the demand gap, nominal GDP could return to trend. But growth seems it would still suffer until we returned our capital stock to trend, where capital stock is broadly defined to include all forms of capital, including intangible capital as in the education example above.

It seems tempting therefore to state that we will experience a “secular stagnation” (and it appears there must be a terrific publication opportunity for economists on that topic!). Yet with sufficient stock and a filled gap, I cannot think of a reason the yield on that stock would not resemble historical yields, thus recovering growth and productivity to trend.

Technological innovation would seem to be dominated by the sheer quantity of capital. We are capital short.

JDH wrote:

“A boost in aggregate demand can lead to higher productivity for reasons of simple accounting. Suppose you are operating a retail store and have the same number of employees today as yesterday. If more customers show up to buy today, your measured productivity (how much you sell divided by the number of hours your employees put in) is necessarily going to increase. If the demand stays high, you might find it necessary to hire more workers to meet the higher volume. But since many tasks (such as security, cleaning, and maintenance) won’t double when sales double, there will still be a gain in measured productivity when demand goes up. Something similar is true for many manufacturing facilities that have significant underutilized capacity.”

Professor,

This sounds like it was written by a shop owner in the 17th Century. Accounting is not modern scientific economics that grew from the insights of Adma Smith and those who followed him. If the shop keeper of your retail store in your example was running his shop in the old Soviet Union he would understand that an increase in spending (demand) would simply clear the shelves sooner and he could go drink vodka earlier than if people bought less. He would understand that demand is always there and simply allowing it to manifest itself by increasing the amount of money will simply allow people to buy scarce resources sooner.

The demographic change should also be an opportunity rather than a drag on the economy. Those who are growing older should have more disposable income and producers should be satisfying their wants and needs, but the disposable income of seniors is eaten away by government and producers are restrained. Innovaiton is stalled by regulation and taxation so we are stuck with existing production run by managers rather than entrepreneurs. New ideas are shelved so we can stimulate demand for existing systems based on old ideas.

Our economy being based on a combination of mercantilist and socialist principles gives us the worst of both worlds. The only solution is economic freedom not top-down cenrtal planning.

If you think that productivity growth is largely a function of the growth of the capital stock per employee the data on this is not encouraging.

It has been on a secular downward slope for decades, especially if you look at the net data that incorporates the point that IT equipments seems to have a significantly lower life span so that an ever greater share of the gross capital spending reported in the GDP accounts is just replacement capital –we’re having to run faster to just keep even. I keep trying to come up with a reason to expect the capital stock per employee to improve and keep failing.

As far as the expectations that over the next few years real GDP growth will improve so cyclical productivity will also improve I’ll just point out that this has been the consensus forecast for some 5 years. What will change that will cause this forecast to be more accurate than it has been over recent years?

Spencer,

I find myself asing myself what is wrong with myself when I start agreeing with you. There is nothing that is encouraging more capital or greater exploitation of innovation.

I’m glad JDH brought up the Gordon paper. I read it about a week ago, and while Gordon didn’t say anything that he hadn’t said at one point or another over the last six months, he laid out the argument in a succinct and powerful way. I thought the paper deserved more attention that it was getting in the blogosphere. It’s a disturbing paper because Gordon is talking about a permanent level shift in potential GDP. All that said, I think there are a few things that Gordon doesn’t catch. First, it’s possible that productivity growth back in the 1950s & 1960s was overstated. We measure productivity through GDP, with the emphasis on “gross” product. A better measure would be “net” product because that’s what affects our ability to consume over the long run. If we went back in time and correctly priced the exhaustion of natural resources, then I suspect measured productivity growth would have been lower than it is. Waste should not count towards greater productivity. Secondly, our NIPA tables were designed around a “goods” based economy. Today’s economy is much more service oriented, and productivity in the service sector is a lot harder to measure. In a goods based economy “learning by doing” tends to show up as depreciation of capital equipment; but this isn’t true in a service oriented economy. Third, today’s economy puts more emphasis on the production of public goods, which are likely undervalued in the NIPA tables. Finally, and on the downside, it’s time to revisit the question of dynamic inefficiency. What Mankiw said 20 years ago may no longer be true.

Some good points here but a few counterpoints are worth considering:

1. Service sector productiivity is harder to measure because service sector output is harder to measure. But it is difficult to say a priori whether the trend has been to overstate or understate service sector real output growth. Nominal output is reasonably well measured but the problem is that the price indexes used to calculate real output are questionable. To the extent they do not capture quality increases they overstate price growth and understate real output growth, confirming your hypothesis. However, it is not clear whether service sector price indexes are in fact over- or under-stated.

2. Input measurement is equally difficult for goods and services, perhaps more so for goods whose production tends to be capital intensive and thus puts more weight on the capital services input measure, which requires several key assumptions. Labor input measurement is fairly straightforward for both goods and services.

3. “In a goods based economy “learning by doing” tends to show up as depreciation of capital equipment; but this isn’t true in a service oriented economy.”

On the other hand, many service industries now invest heavily in intangible capital such as software, R&D, training and development, and process improvement. These investments often have long gestation periods and payoffs are many years down the road. This is related to the Solow paradox where he questioned why we saw computers everywhere but in the productiivity statistics. Gordon may be understating the future gains of investments in intangible assets being made now in both the goods and services sectors.

The Employment-Population Ratio – 25-54 years shows this has been a very weak employment recovery, particularly from a severe recession.

The employment recovery was also weak after the 2001 recession. However, it recovered from a much higher level of employment.

Because of the steady rise of women in the workforce, until the mid-1990s, there’s still a lot of idle labor.

My only disagreement is the extent of potential employment.

“A boost in aggregate demand can lead to higher productivity for reasons of simple accounting.”

Put another way, the relevance of productivity as an observed variable depends on the shape of the marginal cost curve. The lower the marginal cost, the more “productivity” results from higher sales. There are books available today with titles like “The Age of Abundance” and “The Zero Marginal Cost Society.” These versions of events conclude that productivity can increase enormously “for reasons of simple accounting,” i.e., that we are already in a position where innovation merely removes jobs, as we don’t really need many more people to double, treble, or quadruple our outputs, at least not in areas where innovation matters greatly. The internal combustion engine created more jobs for drivers than it took, but that is not a universal law of physics in action. Rather, it is simply a contingent fact about where we were in our technological history. The ICE made drivers more efficient; the robot makes autoworkers obsolete. The Luddites were right. They were early, but they were right. This is not to say that closing the patent office is a solution to the employment problem. But it is to say that to an increasing extent, work will be busy work, and some solution other than busywork needs to be found.

If productivity becomes the enemy of employment, then it must also become the enemy of investment and innovation, which makes productivity growth its own worst enemy under our current entitlement paradigm. If I had a machine that could spit out everything anyone in the US wanted to buy, and do everything anyone wanted done, to whom would I sell my outputs? If no one has a job, where would demand come from. Why would I bother to run the machine? More important, why would I bother to invent it?

Moore’s Law says that we are heading in that direction, as robots build things for us, only we are letting the owners of the robots and the fuel they run on have all the outputs. They are inventing and building because the temporary winner can amass a permanent-seeming fortune. No one invents my Everything Machine, but everyone tries to invent a Something Machine, all the while the invention industry closes in on the Everything Machine like an overfished fishery. There is only so much productivity-enhancing invention that can go before the destruction of employment rouses the rabble to very unpleasant action. Unless we find another way to entitle people to outputs, productivity will remain the enemy of the worker and the would-be worker.

This is the problem confronted by the Israelites in Exodus when food falls from the sky. If entitlement is not linked to production, who gets what, and in what proportion? But if entitlement is linked to production, and only a handful of very rich people “produce,” some very rough beast will come slouching our way ‘ere long. All of which is my way of saying that we are keeping our eye on the wrong ball. Productivity will take care of itself. It’s the resulting concentration of wealth that needs to be addressed.

Nice growth accounting exercise.

So, as trend US growth slows, will get-rich-quick type Americans migrate to sunnier pastures?

Will more Americans join monasteries and other spiritual retreats?

Will Wall Street be ‘taken over’ by recent immigrants because earlier comers are too busy meditating or kayaking rivers?

If low inflation rates are now commonly referred to as ‘deflation’ (sic), then maybe slow growth will be simply called the ‘permanent recession’?

Perhaps the USA will simply explode into a paroxysm of violence because without growth there is no point in living?

Perhaps at this point in human development, ‘we’ require a major nuclear war. That way, we can all experience high growths rates during the re-building process. After the radiation clouds subside of course.