The Federal Reserve still would like to do more, but not right now.

The Federal Open Market Committee yesterday released the following economic assessment:

The Committee continues to expect a moderate pace of economic growth over coming quarters and consequently anticipates that the unemployment rate will decline only gradually toward levels that the Committee judges to be consistent with its dual mandate. Strains in global financial markets continue to pose significant downside risks to the economic outlook. The Committee also anticipates that inflation will settle, over coming quarters, at levels at or below those consistent with the Committee’s dual mandate.

In almost identical language that it used November 2, the Fed is saying that it expects unemployment will remain higher than it wants, inflation will likely be lower than it wants, and that it has significant concerns about where events in Europe might lead. In normal times, that trio would surely signal that policy would become more expansionary.

But the Fed opted instead to keep things more or less on hold, again using almost identical language as in its previous statement:

the Committee decided today to continue its program to extend the average maturity of its holdings of securities as announced in September. The Committee is maintaining its existing policies of reinvesting principal payments from its holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in agency mortgage-backed securities and of rolling over maturing Treasury securities at auction.

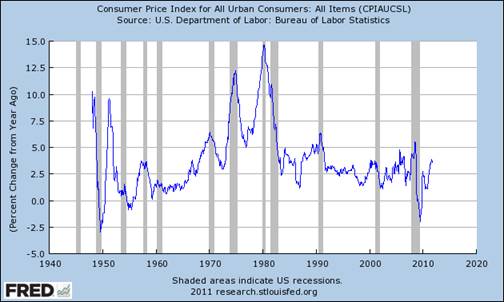

Why nothing more? I think one issue may be that, while the Fed says it has been anticipating that future inflation will come in at a rate below its target, it is much harder to make the case that the realized headline inflation rates over the last 12 months have been substantially too low.

|

|

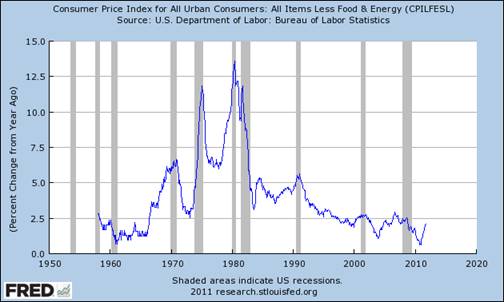

Excluding food and energy, the rate of increase of the CPI has been around 2%. But this measure has been heading up, not down. Although the Fed may regard core CPI or core PCE as a better measure, it is harder to persuade the public that this is the number that should matter, particularly given concerns that food and energy could be among the key prices that would adjust if the Fed were to adopt further easing.

|

My advice for the Fed is to be clear in their minds, and clear in communicating to the public as well, what kind of problems monetary policy can solve and what kind of problems it can’t. In the former category, the Fed can and should prevent a financial panic, and it can and should keep inflation from falling below 2%. I would use the latter as a standard for deciding on any aggressive new quantitative easing initiatives.

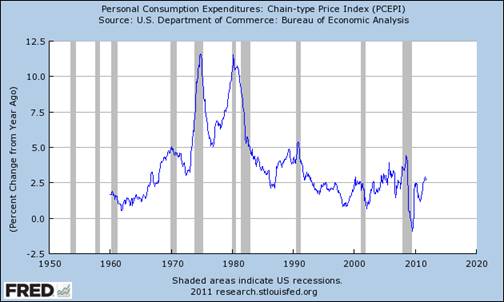

But it’s hard to bring out the bazookas to take aim at deflation when the CPI registered 3.6% inflation over the last 12 months and the PCE deflator 2.7%.

Fisher, Plosser, and Kocherlakota– the three members most likely to oppose further Fed easing– are all rotating off of the FOMC for 2012. And the FOMC statement suggests that the Fed is still expecting those inflation numbers to drop. When and if they do, perhaps then the Fed will act. And of course the Fed stands ready to respond to a potential European financial crisis. But for the time being, it appears that not much has changed.

Idle resources tend to be inflationary (for a given nominal GDP). That is to say if we did not have a pool of idle workers, real output would be higher. Had the fed maintained a steady growth path of 5% per year for nominal GDP, this recession would never have happened.

Professor,

I would love for you to expand on this:

it can and should keep inflation from falling below 2%

Why? Why isn’t zero inflation preferable? Or even deflation?

It seems to me that inflation encourages excess consumption and debt, which isn’t working out so well for us. Sound money would encourage saving and investment.

Now you could argue (and I do) that we are in such a debt quagmire that inflation (devaluing the debt) is the least bad way out of the current particular policy-created disaster, but this avoids the question of why economists assumed that inflation was desirable in the first place.

WSJ: Explaining High Oil Prices

Excerpt:

“The U.S. is no longer in the driver’s seat as far as oil prices,” says James D. Hamilton, an economics professor at the University of California, San Diego, who has researched the relationship between energy prices and the economy.

Growth in demand in emerging markets as a whole is expected to slow from the torrid pace seen in recent years. But forecasts say it will still outpace demand in the U.S. and Europe and will still be strong enough to push oil prices higher. In the major emerging markets that oil investors focus on, such as China, India and Brazil, demand is still expected to grow 4.6% this year and 4.4% in 2012, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

“Emerging markets will probably continue to grow faster than advanced economies,” José Sérgio Gabrielli de Azevedo, chief executive of Brazilian oil giant Petroleo Brasileiro SA, or Petrobras, said earlier this month at the Platts Global Energy Outlook Forum in New York. “The growth pattern of those economies is more energy-intensive than [first-world] growth.” He added: “The era of cheap oil is over.”

Link: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203833104577072301052759854.html?KEYWORDS=explaining+high+oil+prices

Some Global Net Export (GNE) and Available Net Export (ANE) estimates for 2011, based on just extrapolating the 2005 to 2010 rates of change.

Here is what I came up with:

2010 Numbers (BP + Minor EIA data, Total Petroleum Liquids):

GNE = Top 33 Net Oil Exporters, mbpd (& five year rates of change):

Production: 61.9 (-0.1%/year)

Consumption: 19.2 (+2.7%/year)

Net Exports: 42.7 (-1.3%/year)

China & India Net Imports, mbpd (& five year rates of change):

China: 5.0 (+8.3%/year)

India: 2.5 (+6.6%/year

Chindia: 7.5 (+7.7%year)

2010 ANE = GNE – Chindia’s net imports = 35.2

If we extrapolate the 2005 to 2010 rates of change for production & consumption for top 33, we get the following estimates for 2011:

Production: 61.8

Consumption: 19.7

Net Exports: 42.1

If we extrapolate the 2005 to 2010 rates of change in China & India net imports, we get the following estimates for 2011:

China: 5.4

India: 2.7

Chindia: 8.1

Est. 2011 ANE = 42.1 – 8.1 = 34

This would be a 2010 to 2011 decline of about 1.2 mbpd in ANE, versus the volumetric average rate of decline in ANE of about one mbpd per year from 2005 to 2010 (approximately 40 mbpd to 35 mbpd).

I suspect that the ongoing decline in ANE is why Brent is going to average around $111 for 2011, versus $97 for 2008.

Note that Chindia’s combined net imports, as a percentage of GNE, rose from 11.0% in 2005 to 17.8% in 2010. The above estimates would put the 2011 ratio at about 19.2%, which would imply that ANE, as a percentage of GNE, fell from 89% in 2005 to about 81% in 2011.

GNE & ANE comment was by Jeffrey J. Brown

The pretense that the FED actually considers its double mandate any more is laughable. If we look at the results over the past 10 years you would have to be blind to think that with over 9% unemployment and a dollar that was sinking like a rock the FED really cares about it “double mandate,” law or no law.

This historical analysis by Brian Domitrovic puts it in proper perspective. While Domitrovic titles it the FED’s Triple Mandate it is actually only one mandate, to fund and cover government excesses. The FED is nothing but a legalized theft machine.

The problem is that even if they expected inflation to be slightly above target, that isn’t really a satisfactory answer. First, it’s arguable whether a 2% inflation target is even the right target. One of the lessons from the Great Moderation is that a 2% target doesn’t give the Fed a lot of wiggle room if there is a deflationary or disinflationary shock. Maybe 3% is a better target. And second, the Fed seems to be operating as though there is an asymmetry in it’s dual mandate. They seem to think that a possible risk of moderate inflation is a bigger threat than the actual risk of very high unemployment. This is crazy. The inflation hawk troika agonzes over the possibility of slightly overshooting the inflation target, but seems completely indifferent to wildly overshooting the unemployment target. Any fool could fill a seat on the FOMC if the only goal was to target inflation. The reason we pay these guys the big bucks and the reason they’re supposed to be politically insulated is because we want an FOMC that has the skills to balance those two mandates. Right now I don’t see much balance. So good riddance to the triumvirate when their terms expire.

From a practical standpoint, monetary policy is too blunt an instrument to credibly target employment/output. They can lean against the wind, but the FED will never be able to hit employment/output targets consistently. Stick to inflation and the dollar.

tj Your comment makes no sense at all. The only reason we care about the rate of inflation is it’s expected effect on future output. High inflation rates tend to signal even higher inflation in the future. In other words, it’s really accelerating inflation that matters, not the actual number itself. The Fed has settled on a 2%-2.5% target because it believes a higher rate is associated with an overheated economy and might generate 3% next year, 4% the following year, 6% the year after that, etc. The problem is that the current target is clearly too low given the slack in the economy. And the Fed is even having problems meeting that target; e.g., since May the CPI-U has gone up by less than half a percent.

Your comment sounds like an excuse for inaction in search of a problem that you don’t really want to solve. Nobody is talking about “fine tuning” the economy, so who cares if monetary policy is a blunt instrument? We need an axe, not a surgeon’s scalpel. Now I would agree that the Fed’s options are limited as long as we’re in a ZIRP environment, but that is not a reason for a “do nothing” policy. The truly blunt instrument is fiscal policy, which is why no one recommends it as long as conventional monetary policy is viable. But we’re way passed that point right now. We need QE3-Plus and strong fiscal stimulus. If the euro goes under (and I think there’s a better than 50/50 chance that it does before the end of February), then we will rue the day that we didn’t get out in front of the potential deflation risk. A failed euro will depress wages globally, and that will set us up for yet another lost decade.

2slugs,

I am sorry, but you are mistaken. The goal of monetary policy is to remove the distortions that unexpected changes in the price level have on household and business decision making. If the FED jumps from one inflation target to the next(as you suggest) then economic agents must factor that into their decision making and efficiency is lost. If, as you suggest, the FED has a meaningful impact on output, then why in the world do we still have an economy stuck in a recession/slow growth state? Wouldn’t they have solved that by now with monetary policy?

The point is that fed funds targeting is irrelevant and the only thing asset purchases do is to increase excess reserves. When do we get the boost in output you imply? How is that going to happen?

tj A steady 2% inflation rate is a stable and predictable change in the price level. It does not cause price “distortions.” A steady 3% inflation rate is a stable and predictable change in the price level and that too does not cause price “distortions.” A steady 4% inflation rate is a stable and predictable change in the price level and that does not cause price “distortion.” Are you starting to see a pattern here? What we want in a price level is stability, not any particular inflation number. Stability is not the same thing as sticking to one and only one inflation target for all time. You are confusing the two. Historically the Fed looked to a 2% inflation target because it believed that a higher level would lead to accelerating inflation. But just because a 2% inflation target was fine in the past does not mean it is fine today. Relationships change over time. The NAIRU level of unemployment drifts over time and so too should the inflation target. That 2% figure was not written down as a sacred number by the macro gods. The current target is too low. The Fed is continually fighting to stave off deflation, which would lead to a contraction in output.

As I said earlier, I agree that in a ZIRP world the Fed doesn’t have a lot of bullets left in its holster, but there are a few things it could do that would help at the margin. The Fed could try to bring down long term interest rates. The Fed could announce an inflation target of 3% or 4% and put out all kinds of policy papers designed to convince those who study the entrails of every FOMC meeting that the Fed is indeed serious about a higher inflation target. But the real boost in output won’t come until there is a Democratic House majority, a filibuster proof Democratic Senate and Obama’s re-election. The heavy lifting will have to come from the fiscal side rather than the monetary side. Short of that I’m afraid we’re looking at another one of Menzie’s lost decades.

TJ and WC:

“The goal of monetary policy is to remove the distortions that unexpected changes in the price level have on household and business decision making.”

The problem is that too low a target ends up being distorting. The CPI inflation rate in the US over the last 98 years has averaged around 3.25%. This is roughly the rate that is built in to many peoples long term expectations, born of experience. An example might be the “fed model” of valuing equities. It makes no sense that equities would be valued higher at lower interest rates, unless there is an expectation that interest rates will eventually revert toward their long term averages as inflation re-emerged.

“It seems to me that inflation encourages excess consumption and debt, which isn’t working out so well for us. Sound money would encourage saving and investment.”

You might think that is what would happen, but the economic evidence suggests the opposite. Take a good look at the ratio of investment (PNFI Private Nonresidential Fixed Investment) to consumption (PCEC Personal Consumption Expenditures):

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=3Rj

If you want to understand what is causing that, it is very likely distortions of the sort mentioned above in the Fed Model. When inflation and interest rates are low, people wrongly believe that stocks are worth more, and homes are more affordable. Asset bubbles actually fuel consumption due to the wealth effect. Others with less wealth see their wages stagnate (which is what low inflation really means), and may initially borrow to maintain spending rather than adjust long term expectations.

In addition, with a floating currency, we should also realize that the price level impacts the exchange rate and thus the trade deficit. Therefore, too low inflation relative to the rest of the world can also cause trade deficits, which can cause more distortion than a mild rate of inflation would.

Finally, a zero inflation rate might be ideal if money was solely held as a medium of exchange, but in the real world it is also held as a store of value. What financial wealth is really, is a claim on future output. But allow too many of those claims to accumulate, and you are essentially committing the output of future generations without their consent. The Capitalist system just seems to function best in the long run when there is a low steady rate at which those claims on future output expire; this simply helps to preserve the incentives which lead to continued innovation and progress.

Ultimately, it seems that whenever we stray too far, for too long, on the low side of that long term inflation rate, we end up with asset bubbles, financial crisis, stagnating real wages, liquidity trap conditions, high levels of economic inequality, and under the modern foreign exchange regime, now also trade deficits (which also help to fuel budget deficits).

Of course we suffer other problems when we stray too far to the high end as well (as happened in the late 1970s). But I think the evidence is mounting that the Fed ought to be steering towards more of a middle ground.

An educative paper from the Federal reserve including a brief outline of its mandate and the evolution of the money supply as a target through three decades (P28).Unfortunately it falls short of covering the “sturm und drang” period of 1995 2011.In essence we are left to the academic definition of discount window as a measure of financial stress, where the non borrowed reserves used to be a cushion.It falls short as well to address the Interest swaps and derivatives as supplementary functions for leveling the interest rates.

http://www.federalreserve.gov/pf/pdf/pf_complete.pdf

Pareto obliges Central banks may have to consider further easing of monetary policies.

Bloomberg “Bernanke Tells Senators Federal Reserve Has No Plan to Aid European Banks”

And European banks will help themselves by trimming their dependency on money markets and selling assets (doubts may arise as to which assets they will sell first)

Bloomberg (EU Banks Selling ‘Crown Jewels’)

In summary and for now, production is more centered on the financial papers than on the function of labour and capital.

Industrial Production Index (INDPRO) coming back to the level of 2010.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/INDPRO