That’s the title of a paper with David Greenlaw, Managing Director of Morgan Stanley, Ethan Harris, head of global economics research at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, and Kenneth West, professor of economics at the University of Wisconsin, which we presented at the U.S. Monetary Policy Forum annual conference in New York on Friday.

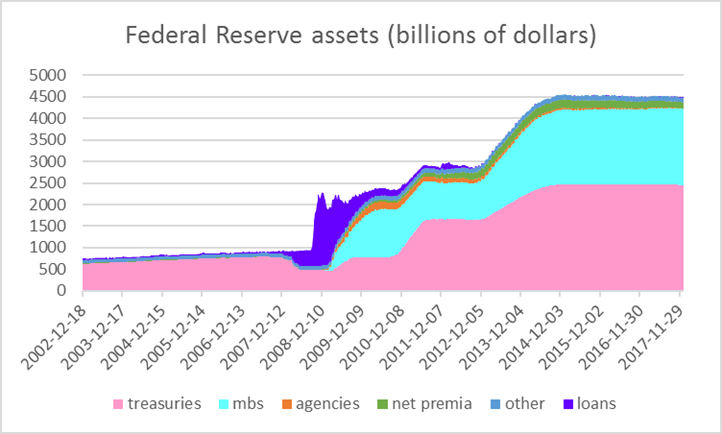

Assets held by the Federal Reserve quintupled between 2007 and 2014. The initial phase of this expansion took the form of emergency lending in the fall of 2008, shown in purple in the graph below. These doubled the Fed’s balance sheet within the space of a few months, but were subsequently repaid and are now off the books. Our paper does not discuss the efficacy of the Fed’s lending programs.

Federal Reserve assets, Dec 18, 2002 to Jan 3, 2018. Wednesday values in billions of dollars. Treasuries: U.S. Treasury securities held outright. MBS: Mortgage-backed securities held outright. Agencies: Federal agency debt securities held outright. Net premia: unamortized premia minus unamortized discounts. Other: sum of float, other Federal Reserve assets, foreign currency denominated assets, gold, Treasury currency, and special drawing rights. Loans: sum of loans, net portfolio holdings of Commercial Paper Funding Facility LLC, Maiden Lane I, II, and III, net portfolio holdings of TALF LLC, repurchase agreements, preferred interests in AIA Aurora LLC and ALICO Holdings LLC, central bank liquidity swaps, and term auction credit. Data source: Federal Reserve H41 archive. Source: Greenlaw, Hamilton, Harris and West (2018).

Our focus is instead on the steady purchases of Treasury securities (in pink) and mortgage-backed securities (in turquoise) carried out in three separate phases popularly referred to as QE1, QE2, and QE3. As Ben Bernanke put it just before he stepped down as Chair of the Federal Reserve, “the problem with QE is it works in practice, but it doesn’t work in theory.” In standard macro-finance models, these should not have had any effect on interest rates or economic activity (see for example Eggertson and Woodford, 2003). More refined models imply potential effects from altering the supply of publicly held Treasury securities, coming from factors such as nonpecuniary benefits some institutions may derive from holding Treasury securities (Woodford, 2012) or preferences or restrictions on the kinds of securities different institutions hold (Chen, Curdia and Ferrero, 2012; Greenwood and Vayanos, 2014). Another possibility is that large Fed holdings of Treasury securities implicitly or explicitly commit the Fed or the Treasury to alternative future policy (Hamilton and Wu, 2012; Eggertsson and Proulx, 2016).

Some of the strongest evidence that these policies work comes from event studies. Researchers have proposed a few key dates on which Fed announcements concerning expansion of QE1, QE2, or QE3 resulted in significant moves in long-term interest rates. These studies have helped contribute to a rough consensus that these programs were successful in lowering the interest rate on 10-year Treasuries by about 100 basis points, thereby boosting consumption and investment demand and helping the economic recovery.

One concern is which Fed announcements get selected for inclusion in such studies. To gauge the importance of date selection, we examined every single day when there was an FOMC announcement, release of Fed minutes, or a policy-related speech by the Fed Chair. We identified 255 such days between October 31, 2008 and December 31, 2017. The graph below plots the cumulative change in the nominal and real 10-year Treasury yields on these days alone. After initial drops with announcements of the onsets of QE1, QE2, and QE3, the overall change in yields on these days of Fed announcements was dramatically up during each of these episodes– exactly the opposite of the claimed effect.

Cumulative change in basis points on days of FOMC meetings, minute releases, and Chair speeches, with zero change imputed to all other days. Shaded regions denote Jan 2009 to Mar 2010 for QE1, Nov 2010 to June 2011 for QE2 and Oct 2012 to Oct 2014 for QE3. Many of the announcement effects should come before or at the start of the shaded areas. Source: Greenlaw, Hamilton, Harris and West (2018).

As a second approach, we looked at the Reuters bond market wrap-up for every day when the interest rate moved up or down by more than one standard deviation. Applying a filter like this was necessary to keep the search manageable and to restrict the search for days for which there was a meaningful market summary from Reuters. We were interested in whether the Reuters summary attributed the move to Federal Reserve actions or announcements. We identified 161 such days over this period. The graph below plots the cumulative change in yields on these Reuters Fed news days. These give a similar impression from the first graph– initial Fed announcements drove interest rates down, but Reuters also attributed subsequent interest rate rises to announcements or actions by the Fed.

Cumulative change in nominal 10-year yield on days on which Reuters reports concluded that news about the Fed was a major factor influencing bond markets (in blue) and on all other days (in gold). Source: Greenlaw, Hamilton, Harris and West (2018).

The most important date in every event study is March 18, 2009, when the Fed announced its intention to increase its purchases significantly, driving the 10-year yield down by a stunning 47 basis points. But after the statement released at the Fed’s subsequent meeting on April 29, the yield went back up by 10 basis points. The latter move is included in both our previous graphs but is left out of most event studies. The Reuters wrap-up for that day offered this summary:

U.S. government bond prices fell on Wednesday, sending yields to 5-month highs, after the Federal Reserve sounded a hopeful tone on the economy in its post-meeting policy statement…. The statement also disappointed bond investors hoping that the Fed would announce an expansion of its program of buying Treasuries, which is part of its credit easing efforts and had helped keep yields from rising.

One possibility is that the initial response in March was based on investor anticipation of a larger program than the Fed actually delivered. A second possibility is that the market was reacting in March not just to the bond purchases but also to the Fed’s information that the economy was weaker than some analysts had believed, a signal that was in part reversed in April; see Nakamura and Steinsson (2016) for evidence on the importance of such signaling effects associated with Fed announcements. A third possibility is that the consequences of the Fed’s bold new plan required time for everyone to analyze and digest. Whatever the interpretation, it seems likely that using the March 18 move as a stand-in for the effects of the overall policy as eventually implemented could well overstate the program’s true effects.

Another example that people often point to is the 9-basis-point jump in the 10-year yield on May 22, 2013 when Fed Chair Bernanke raised the possibility that the Fed might soon taper the pace at which it was buying new securities, a reaction popularly dubbed the “taper tantrum.” Here again we feel conventional wisdom may have overemphasized the role of the Federal Reserve. The figure below plots the cumulative change in interest rates during 2013. The changes on days of Fed statements or attributed by Reuters to anything about the Fed are a very minor part of the broad rise in yields.

Cumulative change in nominal 10-year yield from December 31, 2012 to December 31, 2013. Blue: actual change, gold: changes only on days of FOMC statements, minutes, or Fed Chair speeches; green: changes only on days identified by Reuters as driven by Fed news. Vertical line is drawn on May 21, the day before Bernanke’s first taper warning.

The market’s reactions to Fed announcements of its current program to shrink its balance sheet are also worth noting. As seen in the tables below, the shrinkage began earlier than market participants had been expecting (row one), the drawdown in the balance sheet a couple years out was larger than expected (row two), the Fed paused its rate hikes for only one press conference meeting when starting the shrinkage (row three), and the shrinkage was presented as very much a pre-programed plan (row four).

Median expectations for balance-sheet actions based on New York Fed primary dealer survey and Blue Chip survey. Source: Greenlaw, Hamilton, Harris and West (2018).

But that news from the Fed seems to have played little role in the rise in interest rates last year. Indeed, the cumulative change on days of Fed statements is actually negative. We have dubbed the lack of market reaction to last year’s news about the balance sheet as the “shrinkage shrug.”

Our study raises a caution about the event study methodology. There is a potential tendency to select dates after the fact that confirm the researcher’s prior beliefs about what the effect was supposed to have been. The impact of the Fed’s balance-sheet policy appears to us to be substantially less certain than the current consensus, and the effect could be substantially smaller than is often believed.

For other reactions to our paper see Federal Reserve Bank of New York President William Dudley, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston President Eric Rosengren, Brandeis Professor Steve Cecchetti and NYU Professor Kim Schoenholtz, Wall Street Journal, Reuters,

CNBC, and Market Watch.

The Hamilton and Wu paper you have to pay for. So hopefully I can save someone that 5 link discovery. Although there might be other papers there free, I didn’t try them. But I think it was all Wiley links, so probably they are not free either. Boy, if you are a consumer of blogs (which I certainly have been over most of the last 9 years) have we not seen that federal reserve assets breakdown graph (the first colored graph above) about 5 billion times?? I mean, that one would have been a good one for Menzie to fulfill my Uma Thurman request on.

In all seriousness, I have nothing to add here, other than the small individual investor would probably do a little better if he paid attention to rates. Example—if you know rates have a decent chance to rise in the short term, then don’t let your bank talk you into a long-term CD. And sometimes the moves do seem to be “tipped off” ahead of time by policymakers or conditions that you can guess policymakers will react to. Not saying it’s easy, but I do think it’s doable. This is the best book on the subject in my humble opinion:

https://www.amazon.com/Inside-Yield-Book-Market-Strategy/dp/0134675487

It came out in 1973, and although, yes, the book is “dated”, the basic concepts involved really haven’t changed that much. Another thing to learn that is useful if you like to play bonds is the concept of “Duration”

http://www.investinganswers.com/financial-dictionary/bonds/duration-1288

Moses Herzog: Here’s a link to the working paper version.

@ James Hamilton

I greatly appreciate you putting that paper/link up. University profs are immersed and occupied with many responsibilities and it’s kind and considerate of you and I appreciate it. I have barely scratched the surface of your paper at the New York Policy Forum, but have greatly enjoyed it thus far, and is about as captivating as Economics papers get.

I think you are more than fair with Kenneth Rogoff and there really is no “feel” of you “singling out” him, only his very encapsulating words or very representative words on monetary easing that was common then. I used to be a fan of Rogoff’s (yes, bought his book before the error became public) until the semi-infamous spreadsheet error in his book. Although I suspect you and Menzie would strongly disagree with me, as Rogoff is your colleague, I found that error Rogoff made rather “convenient” as it supported his arguments, and frankly I have always suspected (in addition to the fact it was such an egregious error for a man of Rogoff’s education, that the “error” was intentional on his part. Maybe unfair of me?? Maybe, but when I smell the odor of bullcr*p in the air I really have to call it out.

http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2013/04/grad-student-who-shook-global-austerity-movement.html

@ Prof Hamilton

I should apologize to you Professor Hamilton, my ramblings on Rogoff were related to Eggertsson’s and Proulx’s paper. My comments specifically on your paper still hold though, it is quite an interesting and edifying paper. I am a methodical reader and about 1/2 way through your NYPF paper tonight.

Krugman rarely gets credit for his very healthy and jovial sense of humor (in this case, I think not vindictive at all, just trying to create a laugh).

“Paul Krugman has often quipped that he should take Svensson and Bernanke to Japan with him on an apology tour for having made it seem too easy at the time.”

All the more reason to raise the inflation target?

When the Fed purchases a bond from the public sector, the person who loaned money to the Treasury has been repaid.

Why doesn’t the Fed stamp the bond “paid in full”, and send it along to the Treasury for shredding?

Considering that the Treasury and the Fed are but Uncle Sam’s left and right pockets, those Treasury bonds on the Fed’s books as assets are on the Treasury’s books as obligations. On Uncle Sam’s unified books, these net to zero.

Yet, as I understand it, bonds on the Fed’s balance sheet show up on the Treasury’s books as debt owned by the public, and the Treasury pays interest to the Fed, which the Fed then returns to the Treasury as profit.

Why are experts investigating the Fed’s balance sheet and its effects, and not Uncle Sam’s balance sheet and its effects?

Is it the case that during the peak of the quantitative easing programs, the Fed was buying bonds at about the same rate that the Treasury was issuing them.?

Of course, all of this is done electronically.

Thank you for considering my amateur economist’s questions.

Bernard Leikind: The Fed pays for the bonds by creating deposits with the Fed, of which the Fed is the monopoly supplier. If those deposits are special and scarce, then the purchase may have affects on short-term interest rates. This is the avenue whereby conventional monetary policy is thought to influence the economy. However, you have ably stated why, if we think instead of the operation in pure fiscal terms and altering the nature of debt issued by the unified government balance sheet, in many standard models the operation would be predicted to have no material effects.

BL made the same point I made to the Fed directly and in commentary in the blogosphere.

The Fed took the legal position that the Treasury borrowing and payment to the Fed of monies that redeem a bond are NOT earnings or surplus, the terms used in the remittance statute. The Fed does not have a statutory duty to remit the redeemed amounts back to Treasury under this legal view, so they do not recognize the legitimacy of an accounting offset that in essence erases the public’s debt (when the two parties simply offset the principal amounts and a remittance duty by erasing both positions, before the Treasurt/public borrows anew).

The Fed wants to withdraw excess reserves from the financial system, so their position conscripts the Treasury into selling more debt, placing the new monies into the Treasury General Account in amounts sufficient to redeem the principal amounts on the bonds the Fed chooses to redeem. How.? The Fed does execute an accounting offset to do this. They erase the monies/cash in the TGA as they erase the bond/debt-position.

This is a little weird to me, but it seems that no one is challenging it.

Back to the article – analysts needs to look at the contractionary effects of QE 3. In essence, monies are swept up from the financial system for the buying of the Treasuries, induced by their ability to move their books to different positions when they sell it to the Fed, realizing freed up cash. Since the economy felt no need for this excess flow and freedom, so to speak, we have seen excess reserves for years. That seems of benefit to bank managers sure, but contractionary in effect, potentially. In light of the current shrinkage program of conscripting Treasury as the reducer of monies using accounting offsets after Treasury borrows, it ought to be looked at as being contractionary, at least more likely to be so under the current regimes.

In the next downturn, the Fed should buy state and local bonds, this at least subsidizes current period employment and can also support more infrastructure work now as it encourages their efforts. QE with the dealer network, it seems questionable to me (unless the financial system is collapsing).

@ JF

You close your comment with: “…… it seems questionable to me, unless the financial system is collapsing”

I’m curious, what did you think “W” Bush’s Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson was literally getting on his knees in front of Nancy Pelosi to beg for back in September of 2008?? So she would finally share with him the secret pill she uses to fight early stage dementia??

I do not understand why there is some invective here. Perhaps I am more sensitive than needed.

My comment was about whether QE was a tool to be used in the next downturn where the Fed believes large scale buying would be, in the future, important to stabilizing the financial system. Another part was about how the third round in the past may indeed not have been useful at that time. Another part was to opine that the accounting offset of TGA monies shows how the tool as it is unfolding now is contractionary, suggesting that the third round may have had this effect then, that can be seen to be truly contractionary now (at least of the money supply).

I thought NPR’s “Marketplace” had a better than average show today. They have an interview with Steve Mnuchin (a Jewish gentleman who stood silent with Gary Cohn about 10 feet to Trump’s right as he was defending Nazis in Charlottesville Virginia) which is pretty entertaining. Near to the end of the show they also talk about the process (or exasperating amount of time, depending on your own viewpoint) involved in immigration: https://play.publicradio.org/api-2.0.1/d/podcast/marketplace/segments/2018/02/27/mp_20180227_seg_16_64.mp3

The most hysterically funny and farcical part is when Mnuchin talks about how Trump’s tax bill “doesn’t” add over $1.5 trillion to the national debt.

Jim,

an interesting and highly thought provoking article. Many thanks

What an interesting analysis. In the end of this blog post you state “Our study raises a caution about the event study methodology” but I can’t help that feel the more important caution raised by this paper is the efficacy of LSAPs.

Also, if anyone with the name Ben who just so happens to have a blog at Brookings is reading, know that we would love to hear your take on all of this.

@rtd

The man is not hiding under a rock. He’s written enough about this stuff to probably fill an encyclopedia set, including a recent interview with Yellen.

Also, the authors make it pretty clear in the paper that they don’t question LSAPs at all as a beneficial action. The question is the timing and the amount of LSAPs. They’re not afraid of “going down that rabbit hole”. But maybe they don’t want to go as far down that rabbit hole as Japan did. Or even maybe not as far “down the rabbit hole” as the ECB did. They want to make the LSAPs as effective as that can, which gets back to how they do it and the method involved.

Who said he’s hiding under a rock? I’m just wondering his feelings of this specific piece of new research. If he’s commented, please point me in the right direction and please be certain to use bold typeface.

In any case, I’m not certain that looking at interest rates is the proper approach.

Reading the hardcopy version of yesterday’s NYT. Some good articles, including one by Binyamin Appelbaum. It had this choice paragraph:

“The Fed’s benchmark rate is in a range of 1.25 percent to 1.5 percent, and the Fed does not expect it to rise much higher than 3 percent in the current economic expansion. That’s a problem given that, in the last four downturns, the Fed has cut interest rates by an average of 5.5 percentage points to stimulate renewed growth.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/23/us/politics/federal-reserve-interest-rate-increase.html

The main question entering my head reading about this was “What kind of crazy academics attend such highfalutin conferences??”

@ Menzie and @ Professor Hamilton and @ “anyone knowledgable on Fed Open Market Ops”

You know your mind will wander around to so many questions on this. I mean there are so many variables involved.

For example, and although I am implying something here, I really am leaving this an “open question” and would appreciate an answer from anyone considering themselves quite knowledgeable about “open market operations”. If people inside the Fed are not scared of releasing info like in the following 4 links in a newsletter specifically for “fat cats”—where the Fed members intentionally leaking this data are not afraid of tangible written proof that the data was released early to “fat cat” players before it was released to the general public (and I might add, no one at the Fed being punished with prison time etc) can we not ASSUME they would not be afraid at all to release this data by phone or encrypted channels to friends and cronies??

https://www.propublica.org/article/leak-at-federal-reserve-revealed-confidential-bond-buying-details

https://www.propublica.org/article/what-we-still-dont-know-about-the-feds-leak-investigation

https://www.wsj.com/articles/questions-about-leak-at-federal-reserve-escalate-to-insider-trading-probe-1443650303

https://theintercept.com/2017/04/07/a-federal-reserve-bank-ignored-insider-trading-investigation-when-reappointing-its-president/

Also, if these are big name players and “fat cat” types getting the Fed open market ops data early (we know Grandma Jones is not getting this newsletter for moves in her 401k, right??) we can assume that they can “move markets” and this would deeply impact market expectations, even before the “announcement” which is really NOT an “announcement” for some people.

QE flattens the yield curve to stimulate growth.

Yet, without QE, the yield curve may be flatter.

Given the Dire Straits of the economy in 2009, Ben Bernanke and the Feds sang the right song:

“That ain’t workin’ that’s the way you do it

Money for nothin’ and chicks for free

Now that ain’t workin’ that’s the way you do it

Lemme tell ya them guys ain’t dumb”

Credit to Mark Knopfler, Dire Straits.

In my personal opinion Stanley Fischer is the Jedi Master (if there exists one) on monetary and economic policy. In fact, the ONLY other person I would have chosen over Janet Yellen to be Chairman of the Fed would have been Fischer. Alas, it was not meant to be (and anyway I have no doubt the VSG would have fired Fischer the same time the VSG fired Yellen). These are Stanley Fischer’s words around March of 2016.

“The ZLB and the effectiveness of monetary policy: From December 2008 to December 2015, the federal funds rate target set by the Fed was a range of 0 to 1/4 percent, a range of rates that was described as the ZLB (zero lower bound). Between December 2008 and December 2014, the Fed engaged in QE–quantitative easing–through a variety of programs. Empirical work done at the Fed and elsewhere suggests that QE worked in the sense that it reduced interest rates other than the federal funds rate, and particularly seems to have succeeded in driving down longer-term rates, which are the rates most relevant to spending decisions.

Critics have argued that QE has gradually become less effective over the years, and should no longer be used.It is extremely difficult to appraise the effectiveness of a program all of whose parameters have been announced at the beginning of the program. But I regard it as significant with respect to the effectiveness of QE that the taper tantrum in 2013, apparently caused by a belief that the Fed was going to wind down its purchases sooner than expected, had a major effect on interest rates.

More recently, critics have argued that QE, together with negative interest rates, is no longer effective in either Japan or in the euro zone.That case has not yet been empirically established, and I believe that central banks still have the capacity through QE and other measures to run expansionary monetary policies, even at the zero lower bound.”

https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/fischer20160307a.htm

Ok, I’m reading the bottom of page 44 thru to page 47 now. I mean, really Professor Hamilton, is this an appropriate topic for a peer reviewed economics paper??

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GG2dF5PS0bI

Just finished the paper around 2am on Monster drink. Tons of questions for Prof Hamilton regarding topics in the paper but my guess is he has enough weight with his daily University duties. A more lighthearted and simple question is, does anyone else remember what a rebel and persona non grata KC regional bank Chairman Thomas Hoenig was?? Didn’t seem to like to dance to the FOMC “good ol’ boys” tune.

Are you mentally ill, or too much Monster drinks ?