Probably nothing.

|

In talking about the Fed’s likely next move, it’s useful first to review how we got to where we currently are. The Fed now clearly understands that it overdid the stimulus in 2002-2004, and brought us uncomfortably close to a resurgence of inflation as a result. The high inflation rates for the headline CPI during 2005 might be dismissed as a temporary influence of energy prices. But the upward drift by the start of 2006 of other measures, such as the core CPI (measured by removing energy and food prices from the total) or the median CPI (measured by the price change of the expenditure-weighted median item purchased by consumers), were not so easily ignored. Here’s how Fed Chair Ben Bernanke described his concerns last June:

core inflation measured over the past three to six months has reached a level that, if sustained, would be at or above the upper end of the range that many economists, including myself, would consider consistent with price stability and the promotion of maximum long-run growth. For example, at annual rates, core inflation as measured by the consumer price index excluding food and energy prices was 3.2 percent over the past three months and 2.8 percent over the past six months. For core inflation based on the price index for personal consumption expenditures, the corresponding three-month and six-month figures are 3.0 percent and 2.3 percent. These are unwelcome developments.

One of the key red flags for the Fed was the growing spread that developed in May and June between the yields on nominal and inflation-adjusted 10-year Treasuries. At the end of April Bernanke was still taking some comfort in the fact that these remained below 2.5%:

The stability of core inflation is also enhanced by the fact that long-term inflation expectations–as measured by surveys and by comparing yields on nominal and indexed Treasury securities–appear to remain well-anchored.

But when this spread started to signal a long-run expected inflation rate of 2.7% in the weeks following those remarks from Bernanke, that in my mind was a key factor in persuading the Fed to continue hiking the funds rate all the way to 5.25% in June.

|

As the above graph shows, these long-run inflation expectations have since come back down, stabilizing around a much more desirable 2.3% level. Markets evidently have now have come to share the faith in Bernanke that I have had from the beginning. On the other hand, that faith is predicated on the belief that the Fed is willing to sacrifice some short-run GDP growth in order to keep inflation from returning, and those core inflation figures have been coming down rather stubbornly.

William Poole, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, stated in November that

“‘We need a policy that is disciplined enough to get the job done, but not more so,” Poole told reporters after a speech in Wilmington, Delaware. “If all the information taken together suggests that we are not making progress, then I will be among those who will push for a tighter policy.”

Poole said inflation expectations are “well controlled… The market does believe we’re serious” [about containing inflation]

He reiterated that he sees the outlook for the fed funds rate as “roughly symmetrical,” meaning the chances of an interest-rate cut and an increase are about equal. … ”I can imagine data coming in that would make me want to tighten policy, and I could imagine data coming in that would make me want to ease policy,” Poole said.

And just what might be the circumstances in which the Fed would choose yet another rate hike? I suppose that if those core inflation numbers and nominal-TIPS spreads again surged, the Fed might be forced to consider it. But I view that as rather unlikely at this point, and even if it happened, the Fed would have to be very reluctant to tighten any further. If we want to avoid a recession (which I’ve always believed that Bernanke very much does want to avoid), you really can’t go any farther than we already have, and indeed the verdict is still out on whether a recession is already in the cards based on what the Fed has done so far. Realistically, I think we can take the possibility of another rate hike off the table.

And what about a rate cut? If we do see widespread defaults sending housing into a freefall from here, then I certainly would expect the Fed to start cutting rates, though at that point it would be too late to do much good. But in my opinion, such a prospect, while a tangible possibility, is not the most likely outcome.

And what is the most likely outcome for housing? Even if home sales fall no further, the inventory of unsold homes will continue to be a drag on residential construction, meaning that below-average GDP growth and employment growth will likely continue for some time. Would that be enough to cause the Fed to ease on interest rates? My guess is that it would not. Precisely because a resurgence of those inflation fears would put the Fed in such a tight spot, the Fed may be quite willing to see the current slow growth continue for several more quarters as long as the trajectory appears to be holding stable rather than spiraling down.

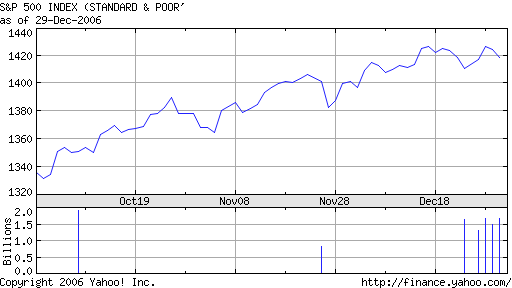

And the data that came in during December seem largely consistent with the claim that things are not getting any worse. Certainly the stock market is not signaling any fear by investors that a recession is about to begin:

|

For the equities of homebuilders in particular, the Dow Jones Construction Index continues to reflect a market consensus that the worst is behind us:

|

Fed funds futures, which started out the month betting on a rate cut by the March meeting, had by the end of the month converged to a predicted fed funds rate for April that is not far from the current 5.25%:

|

That works for me as well. So here’s my call: no change in the fed funds rate until May.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

Federal Reserve,

futures markets,

interest rates,

fed funds rate,

inflation,

recession

I agree with your call, overall. With the dollar so weak of its own accord, it would be disastrous to remove any more of its supports. But to raise rates much more would cause shrieks of pain to emanate from the domestic economy (and Wall Street).

As you show with the data above, there are still plenty of metrics the Fed can point to if it wants to argue there is incipient inflation forcing them to keep rates high.

In fact I suspect we are in a lull in inflation now, as energy prices are climbing their way back up. We’ve been very lucky to have an unseasonably warm early winter.

It is outlandish that Bernanke would read anything about “inflation expectation” in the bond market with the level of FCB involvement. This is in fact borderline dishonest; it certainly shows the Fed not being a good steward of the economy.

I don’t agree that the housing market metrics are looking good. In the past couple months there was a disproportionate influence of the North-East, where all the financial company year-end bonuses were concentrated.

The housing market indices are in a dead cat bounce, in my opinion. A soft landing, and few large-scale write-downs are priced in. It will be interesting to see how this meshes with the trend shaping up of major (e.g. Hovnanian’s) writeoffs and mortgage lenders going caput (mostly subprime, for now).

I would suggest we are already in a recession. Many manufacturing indices are already in contraction. Consumer confidence has been trending lower this year. Retail sales have been tepid for the holidays. Many consumer bellwethers (such as Wal-Mart) have been ailing. Job creation has been tepid this year — overall, not enough to replace a growing population even by the official stats. Plus lots of construction workers and real estate agents are effectively unemployed already but this doesn’t show up on paper. Violent crime has spiked way up (most notably, robberies, at ~10%). Government spending, now a huge swathe of the economy (especially “high-tech”) has surely peaked, with the Democrats with the power to stonewall in the legislature.

As once pointed out on this blog, corporate profits, and hence the market’s level, may be an illusion: they were “overstated” by 20% going into the last recession. I think the effect may be even larger this time, as the higher level of consumer purchases via financing means consumer-centered defaults will take a bigger bite out of profits and revenues, retrospectively.

“Soft landing” seems like serious wishful thinking to me.

The rate of growth in the money supply has been steadily accelerating since Bernanke took over at the Fed.

Here’s a link: http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/usfd/page6.pdf

Pre-Ben the rate of growth of M2 had been in the 4.0% range for many moons,it’s now at 5.3% and accelerating.

So on the one hand the Fed has been increasing rates while on the other they’re boosting liquidity. There is an interesting article in today’s (01/02) Wall St. Journal about the liquidity sloshing around the world and how it’s distorting markets by virtually eliminating the risk premium for exotic investments. Should the Fed ever stop the acceleration,the liquidity situation plus the tremendous amount of derivatives out there could cause problems.

Jim,

The FED is trying to use interest rates and the money supply to control the economy, but they work at cross purposes. Then with these two arrows they attempt to hit a whole bunch of targets, employment, inflation, long term interest rates, short term interest rates, FOREX rates, balance of payments, not to mention “irrational exuberance. The list could go on but hopefully this will give an indication of why they mess things up. It is just the nature of the beast.