I earlier expressed concern (here and here) that insufficient details about the analysis of near-term oil supply prospects by

Cambridge Energy Research Associates had been released to allow outside observers an opportunity to evaluate objectively the basis for their conclusions. The Oil Drum notes that these details are now available from CERA. My impression from examining these is that CERA has good reasons for expecting significant oil production increases over the near term.

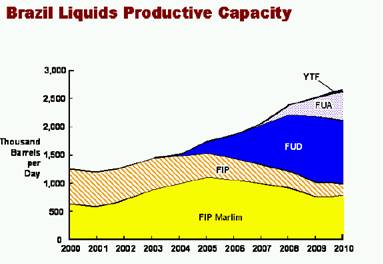

I had earlier shared the Oil Drum’s puzzlement as to why Cambridge Energy Research Associates and Chris Skrebowski of the Oil Depletion Analysis Centre had arrived at such different conclusions about near-term global oil production prospects, with CERA concluding that the world’s oil production capacity could increase 16 million barrels a day over the next five years, while Skrebowski was quoted by Global Public Media as concluding that increased production through 2010 “would almost certainly not be sufficient to offset diminishing supplies from existing sources and still meet growing global demand,” though the detailed copy of this study that I was able to find appeared somewhat more optimistic. The discrepancy between CERA’s and Skrebowski’s conclusions is surprising, since they used essentially the same methodology, namely, a bottom-up, field-by-field tally of major prospects that will soon be going into development. The Oil Drum suggested that the discrepancy might be due to the fact that CERA had completely neglected the decline in production rates from existing fields. This conjecture by the Oil Drum turns out to be incorrect. For example, the graph at the right displays CERA’s projections for Brazil, which show falling production rates from the Marlim oil field. Eyeballing this, CERA appears to have assumed something like an 8% annual depletion rate. This is projected to be more than offset from new fields under development (FUD) and later by fields currently under analysis (FUA) such as Albacora Leste, Marlim Leste, and Marlim Sul.

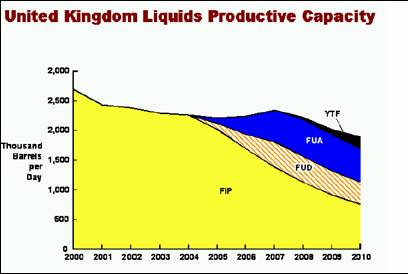

CERA developed their depletion assumptions on the basis of a field-by-field analysis. For example, for fields currently in production (FIP) for the United Kingdom, the graph at the left suggests about a 20% annual depletion rate, partially offset with new projects such as Buzzard. CERA also assumes modest depletion for Saudi Arabia’s Ghawar field.

It may be that these field-by-field depletion assumptions work out to a different total than the overall rate assumed by Skrebowski. However, it is clear that another explanation for the differences in the conclusions is that CERA was including many projects that Skrebowski did not count. For example, I was unable to locate on Skrebowski’s list the 200,000 barrels per day from Sudan’s Adar Yale field, the 170,000 barrels per day expected from Sakhalin II, or a half dozen other big projects that are included in CERA’s total.

This is not to say that CERA could not be wrong in any of these individual estimates or their collective implications. In particular, as CERA has emphasized, the “above-ground” risks to all of these projects are quite substantial, the setbacks to the Gulf of Mexico production from this summer’s storms being the most recent example. While these fields may hold geologic promise, the physical challenges of deep-sea and oil-sand production, and the geopolitical risks in places like Sudan, Iran, Iraq, Nigeria, and Russia are far from inviting. The world has been forced into reliance on these less attractive options precisely because the safe, easy resources are gone.

Still, having the prospect of getting oil from such places seems better than not having any oil at all.

Technorati Tags: peak oil, oil,Cambridge Energy Research Associates

Just look at the CERA graph on UK oil production: the production should have started to recover this year. What really happened:

Scotsman.com News – North Sea Oil & Gas – UK oil production dips 11%

(http:/

/news.scotsman.com/topics.cfm?tid=181&id=745642005)

(The news item is dated Wed 6 Jul 2005. The data is from April 2005.)

CERA has taken account of depletion but over-estimated new production. Here we have a very detailed picture of the UK North Sea oil: http://www.energiekrise.de/news/haupt.html (roll down a bit).

It is clear that CERA is over-optimistic. Nevertheless CERA gives only a couple of years more for the growth of oil production. CERA and Skrebowski agree on the basic fact that there are some new projects and capacity coming online this year and next, considerably less in 2007 and nothing much after that. CERA makes then some optimistic guesses about new discovery after that point. The others look at the dismal discovery trend and make more pessimistic assesments.

Russia is the real key. Its production is on par with Saudi-Arabia but the Saudi production has been far more stable for years. Saudis cannot probably increase their production as they promise but they can keep their production up relatively well for some time. Russia has been very volatile and the present data seems to indicate that they are facing depletion right now. The production reached top in September 2004 and has been declining since. The downward slope can be steep. It may be recalled that the Russsian oil authorities have themselves predicted that Russia may cease to export oil in 2010. This is basically what the ASPO newsletter country assesment says. We can already see that CERA predictions are already depreciated.

The ASPO official 2004 liquids scenario seems still to be the best one. And it says that the peak will be in 2007-2008.

A note from the Moscow Times referencing a Bloomberg article on the slower growth of Russian production (and this from a govt source!):

“Russia pumped 1.3 percent more crude in August than a year earlier as output growth at companies led by TNK-BP compensated for sliding production at Sibneft and Yukos.

Output rose to 9.49 million barrels per day in August from 9.37 million bpd in the year-earlier period, according to the Industry and Energy Ministry. The country in July increased crude output by 1.2 percent to 9.45 million bpd, the slowest annual growth rate this year. (Bloomberg)”

CERA needs about 2.2% annualized to hit its Russian target – not a good sign when the run rate in the first year is half the level.

Picked this up from elitetrader’s forum.

It makes a lot of sense…makes one wonder.

“In 2000 I worked in the Gulf of Mexico for two different OSV companies

that provided support services to the “oil patch”. The two companies did

very different work for the oil companies so I got to get an eye full.

The first thing that I’d like to expose is the fact that nearly all of

the new wells in the gulf are immediately capped off and forgotten

about. I saw well after well brought in only to see them capped off and

left. Oil or natural gas it didn’t matter. I asked a couple of petroleum

engineers what exactly was going on and I was told by both (they worked

for different companies) that there was no intention of bringing that

oil to market until the “price was right”.

That wasn’t the only bogus thing that was happening. Seismic technology

had developed to the point that they could not only tell the companies

where the oil was but how much oil was there. All they had to do was go

out and stick a straw in and suck it out. They didn’t. Once again, the

oil prices weren’t right. When they are ready and want it they know

right where to go get it.

Another lie I’d like to lay to rest is the one about all of the

“terrible damage” done to the oil platforms and rigs in the gulf during

hurricanes. This is how they justify the price spikes that occur because

of lost production. If anyone cared to see this for themselves they

could travel the entire Gulf of Mexico in search of destroyed oil rigs

and they won’t find any- not one. There is a damed good reason that this

is so and that reason is that they are built so well that a hurricane

can’t touch them.

Think about it . If you’re going to build something in an area where you

are guaranteed to see 150-180 mph winds, storm swells up to 60-80 feet

and it will happen year after year, how would you build them? Out of

chicken wire and duct tape? Hell no and they don’t. The platforms are

designed to offer almost no wind resistance and the majority of

platforms are at least 120 feet above the water level. They are built so

well that several of them have suffered direct hits by watercraft of all

sizes with little harm. They were damaged but they were far from destroyed.

The reason that I know how well they are constructed is because for

awhile I worked with a company that salvaged derelict oil rigs. When the

wells ran dry and the oil companies didn’t need them any more the

company that I worked for would buy them, take them apart, haul them

back to land, refurbish and then resell them. It is an incredible

process to take these things apart because they are constructed so well.

I’ve worked on the boats that hauled explosives to the job sites to

speed the disassembly process.

Another lie regards the “burp” in the supply line. Oil companies are as

stingy as any on earth and one of the ways that they cut costs is to

eliminate the number of people that they need on a rig to keep it

running. Most active wells are totally automated and require almost no

human intervention. The oil companies have guys that travel from rig to

rig via helicopter to check on things periodically but most never see a

human on them unless something goes wrong or some maintenance is needed.

During a hurricane about the only rigs that need to be evacuated are the

drill rigs that have workers on them. The active wells and pumping

stations are controlled by remote control from the shore and if it

weren’t for the evacuation of land based personnel from areas where

there is danger from the hurricanes these things could continue to pump

right through the worst hurricane.

So, regarding a burp in the supply chain there shouldn’t be one and that

is because most of the oil from the Gulf of Mexico goes to the refinerys

at Port Arthur or other points in Texas and the tankers from the middle

east go to Galveston to offload.

When oil moves across the Atlantic during hurricane season the tanker

traffic may have to kill some time to let a storm get ahead of them but

once it does they haul ass right behind it. Anyone who has seen how fast

an oil tanker can move in open water will tell you that they don’t

dawdle around. Most of them can move around 30-40 knots and for a ship

that size that baby is moving on. The only reason they would have to

kill any more time would be if a hurricane suddenly changed course and

was headed for Galveston. So far this year that hasn’t happened. So why

the “break” in supply?

Everything that we hear about oil from the oil companies is a big fat

lie. Have we hit “peak oil” as a good many insist that we have? I’ll

make a wager with anyone who would care to take the bet. I bet that when

oil hits $100 a barrel (I have a hunch that’s the target price) there

will be no shortage. Any takers?

Denny Meredith

Louisville, Ky.

USA”

The thread is quite interesting:

http://www.elitetrader.com/vb/showthread.php?s=&threadid=54905&perpage=6&pagenumber=1

Some comment on the Russian oil production. The production has been basically flat from September/October 2004. But 2004 saw still a considerable increase every month up to September. So even if the production is flat or decreasing a bit we get a year-to-year monthly increase up to August 2005. It is already clear that this year the total production will be higher than 2004 but growth will be much slower than last year. The coming six months will show if Russia will begin to decline again (the first, absolute peak was in the end of ’80s).

“I bet that when

oil hits $100 a barrel (I have a hunch that’s the target price) there

will be no shortage. Any takers?”

I’ll bet that if there will be no shortage the price will not be $100 a barrel.

“For example, the graph at the right displays CERA’s projections for Brazil, which show falling production rates from the Marlim oil field. Eyeballing this, CERA appears to have assumed something like an 8% annual depletion rate. This is projected to be more than offset from new fields under development (FUD) and later by fields currently under analysis (FUA) such as Albacora Leste, Marlim Leste, and Marlim Sul.”

I am from Brazil. Albacora Leste, Marlin Leste, and Marlin Sul are deep water fields. Petrobras SA is developing underwater robots to explore these fields because humans cannot work under the high underwater pressure at these fields. The oil plataforms too need advanced thecnology to work there. So, it is not cheap get crude oil form there.

I not believe that these new fields will be developed fast enough to offset Marlin oil field’s depletion. The thecnology just need be developed to make that possible and that thecnology will be NOT cheap. They will need too much money to explore oil there. Finally, they possibly will need crude oil price’s above U$ 50 to make these new fields profitable. So, simple economic rules here: if the oil crude price isn’t stable above U$ 50 no oil suply from these new fields.

So, the CERA predictions for Brazil oil production are plain wrong. I am sure that CERA predictions for other countries are wrong too. If anyone look at the data for oil production now at 2005 it is possible to see that a lot of CERA’ predictions are wrong just NOW.

I don’t believe that CERA predictions for cheap oil and crude oil production will happen. These two predictions are mutually exclusive. We will not see the new oil fields being explored while they aren’t profitable. But the CERA prediction is that the oil price will be U$ 25 because the new fields around the world will give to the market more supply. The new fields simply aren’t profitable at these low prices because most new fields aroung the world are deep water fields or are heavy sour fields. Both are dangerous to work and they have higher coust to be explored.

As I work for Brazil’s Federal Governement I know that the best policy to my country is develop ethanol and biodiesel production. Ethanol production from sugarcane is more economical than ethanol production from corn and if the crude oil’s prices stay above U$ 40 it is cheaper produce ethanol than produce gasoline. So the crude oil can be better used to produce diesel that is used by trucks and trains while we develop the Biodiesel thecnology to make the biodiesel a cheaper substitute to diesel. And the crude oil that is explored here at Brazil is heavy oil that is cheapest used when used to produce diesel (to produce gasoline it need be cracked first).

The real problem is gasoline’s addiction. We are working at that now… because SERIOUS goverment officials need work for the Nation welfare. We cannot work with optimistic assumptions that are not realistic and worse, optimistic assumptions from a group that made wrong assumptions before at 2001. That is wish thinking and delusion. I don’t see oil companies making the same predictions that CERA made. Serious governments need be preparated to work when something get wrong (for example, a natural disaster), so optimism isn’t a good policy.

Joo Carlos

Sorry the bad english, my native language is portuguese.

If indeed oil companies are leaving oil in the ground, I would argue that’s strong evidence for peak oil. The reason to leave the oil in the ground is that they think prices will be higher in the future (ie supply will be tight and cause demand to have to throttle back relative to what it would have been had prices been modest). They are insiders and have better information than outsiders, and they are acting on this information to maximize their returns. If they thought supply was going to be ample in the future, causing prices to go down again from their current high levels, they’d be selling all they could at the current prices.

I also think it’s a good thing for society that they are doing so. It’s much better to constrain production now (in order to jump start conservation efforts) and then have some shut-in production to soften the decline rate later than to pump flat out now and then decline very rapidly later.

I checked the latest Brazilian production data (July) and they really have increased production from new fields and are right on CERA track now. But CERA expects Brazil to grow much more in the future. We will see if it can. Joao gave interesting information on this. But North Sea is not on CERA track nor is Russia. This means that some producers should be on a considerably higher track to compensate this. I doubt that.

And we have now seen that the Katrina supply disruption will be covered from storage, not by using spare production capacity. This seems to mean that the Saudis have really been pumping at maximum capacity. So nothing we see now confirms the CERA scenario.

I agree with Joao. Wishful thinking is dangerous.

Thank you Joo Carlos. Your comments made for interesting reading.

The comments by Mr. Carlos note a significant factor in crude supplies is the anticipated cost of both exploring, and putting into production deep water oil.

The basic model for capital investment is anticipated cost, anticipated production (dollarized), the cost of capital, and the perceived risk.

The future price of crude oil is an obvious factor in the equation, and the future value of crude is one much talked about. However, the other elements in the equation are also variable, and there are some fundamental changes taking place.

Political stability/instability is always a factor in measuring risk, and I the short term results reflected in Russia’s oil production probably has as much to do with the prosecution of Yukos management for tax evasion resulting in a diversion of capital and attention both for Yukos, but also for other companies with similar exposure. To the extent that higher oil prices subsidizes local governments there should be some increase in perceived stability.

Technology has always been a factor in the industry, and while some would lead us to believe that geology is a perfect science, one only need to follow the results of the exploration drillers to find that there continues to be a significant number of developmental properties that cannot support economical production. Longer term high prices can change the value of some of these properties.

Capital allocation has two dimensions. With higher oil prices, the cost of drilling rigs has escalated significantly. If prices are perceived to remain at near the $60 level, the drillers will make additional capital investment bringing down the cost of drilling. However, many of the existing companies remember the last cliff in oil prices and are likely to be quite conservative.

The most likely imbalance in capital flow to the industry is likely to be the modern day 49ers. The recent increase in the amount of futures contracts demonstrates that the industry has attracted many new investors. These folks are likely to buy into new exploration projects, and finance new drilling equipment that seasoned drillers would think are not prudent. Maybe tech companies are worth 300 X earnings. Maybe oil companies are worth 300 X earnings.

There are two inevitable results of gold rushes. Increased capital will be available. Some individuals will take advantage of this interest to make money drilling dry holes for the speculators and for many the opportunity will be wasted. However, the supply is likely to increase simply because of the increased drilling activity, and the fact that some will be willing to put into production wells that are viable only at $70 per barrel because you have to keep your investors happy.

Katrina, by creating a price bulge, is as likely to be as effective in bringing long term supply up as it apparently is in bringing short term supply down.

Bill

I think the efforts by ASPO, CERA, ODEC, this blog, OilDrum etc are exactly what we need. I personally don’t look at all the details, and am glad someone is. But then again, there is merit in saying that one can get too caught up in the details–and I’m not critizing, details are important.

Here’s my gut feel on this whole issue, and as a private energy investor, I take this whole issue seriously. Oil was darn cheap for years. Very cheap. I won’t quantify that. I don’t think it’s necessary. Now it’s more expensive, though still relatively cheap. Oil fields are depleting. But there is a lot of great technology that has been developed in the last twenty years, and additional progress to be made (now that the oil companies are swimming in $$$) to start tapping into lower quality sources of oil.

You cannot quantify my statements of course. But I (1) believe in peak oil (2) think we are currently running up into a production limit that will ease through (a) demand destruction (or growth destruction at the last) as people start shifting to more efficient transport and will stop jumping onto airplanes to parasail in the bahamas over the weekend and (b) we see a sizeable increase in the development taking place in the oil industry–read more jobs in the oil industry.

Take Russia as an example. Now I’m not a mindless free market zombie. They went to Russia to apply their ideas and pretty much wrecked the economy (then went to Iraq to wreck that place)–while China using the “asian method” continues forging ahead (ok, apples and oranges, still some truth I think). But that aside, does anyone believe that Russia’s oil patch is run efficiently? That new development is run efficiently? I’ll bet not. Is anything in Russia run efficiently? I’ll bet not.

Seems to me that additional R&D in the oil industry, over the coming, say five years, will make a big difference on the up side and finally, thank goodness, we’ll not have single individuals cruising down the highway in a Hummer.

I’ll end with a comment made by a Chinese man in my last companies China office. We were talking politics and I brought up energy issues. He said “I go to American, I see a teenage girl driving down the freeway in an SUV. She weighs less than 100 pounds. She drives a car that is thousands of pounds. Why?” My answer: “cause we can, and we’re pretty damn stupid.”

This SUV driving teenage girl is an incredible inefficiency. From a national or global perspective, I consider it a very short-sighted misallocation of capital. It will be wrung out. And it will buy us time.

In a recent news release, the U K ministry in charge of North Sea leasing activities noted that the number of blocks awarded was the largest since 1972,

In addition, it was noted that many small companies were successful bidders for these blocks.

The current round of proposals were submitted by June 9th, so Katrina had no impact on the original bids. However, the winning bidders have a period of time to close on these blocks. As I noted perviously, I suspect that current prices will attract capital from speculative investors and so I would anticipate a relatively high closure rate.

The amount of capital available for oil drilling, and completion costs is being demonstrated. On the longer term, other economic developments will compete for this capital. The tech company bubble in the stock market of the last half of the 1990’s drew capital away from many other businesses. Speculative housing investments appear to be peaking. Oil could be the next great bubble.

Bill

Another aspect to this. Youngquist wrote Geodestinies in 1997. It’s a grand tour of earth’s resources. He says that 75% of US wells are stripper wells, with an average production of 2.2 barrels a day. There are 452,248 of them in 1994. A stripper well produces, by definition, less than 10 barrels a day.

His point in bringing this up? A significant portion of the worlds production is produce by low volume wells. Looking at the CERA and ODEC numbers simply does not take into account the potential for production that exists if capital is available. It’s not cheap oil, but there was no incentive to produce lower volume wells if OPEC could blow you out of the market with a sudden production increase. Once we are in a world in which there is no threat from OPEC, I think we will better understand the production possibilities that exist–around the world.

Peak Oil is NOT about running out of oil… it is about running out of CHEAP oil… big difference.

Oil at $100/bbl does NOT conflict with the Peak Oil model… there will be NO shortages of oil, only shortages of cheap oil… if you are willing to pay, it will be found and or created (as in syn fuels or bio-diesel)… all that matters is the price.

Sure there will be economic rationing… maybe even a reduction in demand & consumption… so be it… that is how markets work.

BTW – I worked in a US fuel ethanol facility and Joao is correct in that ethanol from cane is generally a better option than ethanol from corn at this time… but ONLY if labor is third world cheap. Cane is far more labor intensive… even modern cane processing… but corn is far more capital intensive… FAR MORE. Especially if the corn mill is a ‘wet mill’ and produces other products (corn oil, various blends of feeds, citric acid & glutamate, sugars, starches & ethanols)… but the wider product mix can favor corn again… It really comes down to the ratio of cost of capital vs cost of labor.

Bio-diesel production as currently done is a problem however in Brazil & US alike… soybeans are just too valuable to divert to fuel… too many hungry people. Granted the beans are processesd to seperate the oil from the more valuable food protein & starch… but oil is important too.

Plus the processing is quite energy intensive… I haven’t seen an energy balance but bet it isn’t pretty – especially considering how much energy is required to grow, harvest & transport beans.

The key to bio-fuels will be developing better feedstocks & processes. High oil yeild crops for bio-diesel & high yeild fermantation processes that can utilize cellulostic feedstock for ethanol… If ligno-cellulostic feedstocks can ever be economically fermented… then everything from lawn clippings to sawdust can be turned into liquid fuels. Right now the problem is the rates & yeilds – both terrible & so cost is high.

With oil approaching & maybe topping $100/bbl there will be a greater push to develop these kinds of processes & feedstocks. Count on it.

Elliot, I agree with many of the things you say, but the details are also important. You said:

“people stop jumping onto airplanes to parasail in the bahamas over the weekend”

Well, basically you’re destroying tourism! I live in Spain, tourism is like 80% of our GDP, we are the second destination in visits (after France) and in income (after the US). And we are just starting to realise that we can’t compete anymore with cheap destinations (like Greece, Turkey, Morocco or even the caribean), so now in Spain everyone in the tourism sector wants to turn into “quality tourism provider”!

This is just an example.

I think the real challenge is to accomodate a global economy addicted to cheap energy to the new paradigm. And we don’t have made any preparations (we even barely agree in assesing the situation!), and the options will be expensive and I fear, painful…

Ah! my mind hurts when I try to figure out everything that’s involved!

Bill Ellis wrote:

“Technology has always been a factor in the industry, and while some would lead us to believe that geology is a perfect science, one only need to follow the results of the exploration drillers to find that there continues to be a significant number of developmental properties that cannot support economical production. Longer term high prices can change the value of some of these properties.

[…]

There are two inevitable results of gold rushes. Increased capital will be available. Some individuals will take advantage of this interest to make money drilling dry holes for the speculators and for many the opportunity will be wasted. However, the supply is likely to increase simply because of the increased drilling activity, and the fact that some will be willing to put into production wells that are viable only at $70 per barrel because you have to keep your investors happy.”

While geology isn’t a perfect science, geology can make more accurate predictions than economy. Geology is a physical science while economy is a social science…

There are some issues that economists constantly forgot when making predictions for the oil future:

1- thecnology ISN’T magic: Arthur C Clarke get it wrong, there is an easy way to separate advanced thecnology from magic, no advanced thecnology can go AGAINST the physical laws because no thecnology can work against the physical laws. So, anyone that have a minimal knowledge of Physics can separate advanced thecnology from magic, just make a few search to see “how airplanes can fly”, the physical principles are plain simple and a 10 year old child can understand it.

Thecnology will ever have physical constraints and there are a coust associated to these constrants. The new fields have a PRODUCTION COUST higher than the “cheap oil” fields and there are physical principles making that cousts higher. Thecnology can lower that cousts but never will make the new fields have the same production cousts than the old “cheap oil” fields. The “cheap oil” fields are on land and they have high pressure that make the oil flow to the surface. The deep water fields need that an oil plataform be built and that oil plataform need be built to be stable at high sea (oscilation is bad for drilling and high sea have weaves). Deeper the oil fields, more thecnical problems need be solved by the oil plataform engineers, more expensive will be the oil plataforms and more expensive will be the oil extraction.

The cousts to extract crude oil from these old “cheap oil” fields are (or better, were) cheaper than the cousts to get potable water (potable water: they need a bomb to get water that need a chemical treatment for be made potable, so it is not a mystery that drinkable water have a higher price than “cheap” crude oil, drinkable water have a higher production coust, duh!). However, the cousts to explore crude oil from deep water or to explore heavy sour crude oil (that have H2S high concentration and that gas is dangeous: it is toxic and it have a bad habit, it explode too much easy) are a lot higher than the cousts to produce drinkable water (again…duh!).

2- “[…] the fact that some will be willing to put into production wells that are viable only at $70 per barrel because you have to keep your investors happy” – to make the investors happy the oil companies NEED profit. If the coust of production is HIGHER than the crude price there is NOT profit. It is cheaper simply STOP the production than have a negative profit. Geologists working at oil field have a good gasp about how much the oil production will coust.

3- Oil prospection (drilling) isn’t oil production. These two processes are separated. For example, deep water fields have diferent plataforms for drilling and to produce oil. But frequently economists assume that oil prospection (drilling) is the same than oil production.

“The first thing that I’d like to expose is the fact that nearly all of the new wells in the gulf are immediately capped off and forgotten about”

Well, that is a frequent pratice. Geologist can say with almost perfect acuracy how much will COUST to produce oil at any field. The geologists first need find the oil, so there are the prospection drillings. That first drill will give crude oil samples that will be chemically analysed and the geologists will analyse that first well production for some time to calculate how much pressure the oil have. It is physical- chemical analysis, so it is a LOT MORE EXACT than social analysis (sociology and economy). The geologists will have and acurate prediction about the coust for produce oil at that field. Oil quality is important because low quality oil (heavy and/or sour crude is more expensive for refine) will have lower market price than light sweet crude. The oil pressure data will give information about how much oil will be produced each day.

The thecnology is making the coust for PROSPECT oil fields cheaper (sonar, digital analysis). It is easier now NOT drill a dry well. However, the thecnology cannot make the oil production be cheaper than the “cheap oil” fields where the oil simply flow to the surface. Any thecnology that use bombs or water injection to make the oil flow to the surface will make the oil procduction coust be more expensive. And heavy sour crude will be heavy sour crude and not light sweet crude, so to produce heavy sour crude will make the profits lower.

The new oil fields have both problems. They are more expensive to produce oil and the oil have lower quality. So, higher production cousts and lower market price for the oil produced. Geologists can make acurate predictions about the oil qualtiy and the oil production per day, so it is easy for the oil companies CEOs predict if is profitable PRODUCE oil at that field.

4- “There are two inevitable results of gold rushes.” – Oil prospection and oil production are SEPARATED processes. So there are not inevitable results here. CERA predictions make a mistake when they mislead OIL PROSPECTION THECNOLOGY with OIL PRODUCTION THECNOLOGY (sorry, that is a PLAIN mistake, they show that they don’t know the thecnology).

Oil prospection will give the data to predict if it is possible get profits from oil production. but oil prospection and oil production are separated events, they happen at diferent times. Oil companies can control WHEN they will start production. They simply can cap the prospection well and “forgot” the field. What factor will determine how much time the oil field will be “forgot”? Crude oil price and the field oil production’s coust. No company will produce oil from a field if there is NO PROFIT.

The oil companies have enough management freedom for decide WHEN they will start to produce oil from a field. It is a mangement decision because prospection and production are separated events. It is not inevitable that a prospected well will be a production well. So, Fields Under Develepment (FUD) will be not inevitably Fields Currently in Production (that is other wrong assumption that CERA made). They will start to produce when there is a market oil price that will cover the field’s oil production cousts and give profit. The oil companies can manage when FUD will be FIP. so, CERA is again wrong when predict that the FUD will be FIP

The oil production coust will determine when is viable (when there is profit) to make FUD go FIP. But the new fields HAVE a HIGHER production coust, so the market price need be higher to be profitable produce oil at these new fields. Basically, the oil companies will wait the “cheap oil” dry before start to produce at the fields that have a higher production coust. So, CERA is again wrong when predict that the current FUD will be FIP and the oil market price will be US$ 25.

IMHO, CERA make too much mistakes to think that they are making an acurated prediction for the future oil production and for the future oil prices.

Joo Carlos

Sorry the bad english, my native language is portuguese.

The half a million stripper wells in in the US produduced a million barrels a day in 1994. That makes 5% of the US oil consumption.

Hubberts curve tells about all this. In the end the new discoveries are smaller and smaller and cannot match ongoing depletion. But this also means that the oil will never end. The smallest deposits remain.

The Russian oil production did peak already one and a half decades ago and there are no chances to reach those levels again. The Yukos debacle might have some effect but the second peaking is coming inevitably. It is simply not possible to keep up the past growth pace. It is a rule that no oil producing country likes to speak about depletion. They like more to complain about lacking investments. But this is mostly only another way saying that there are no more fields worth investing in…

Nobody is denying that new investment can bring up production – somewhat and for some time. We have seen an extraordinary oil production growth during the few last years. The higher prices have really done their job. But at the same time those who have pointed to this and said that the markets are working also here (the economists) have had wrong predicting the oil price. Those who have talked about the Peak Oil (the geologists) have had so far wrong but right in predicting rising oil prices. No wonder the discussion is leading nowhere.

We see that both the economists and the geologists have failed on their own field. The geologists could not predict the supply and the economists failed in predicting the demand.

The supply did react to rising prices by bringing in existing spare capacity, overproduction and new smaller, high-cost projects. All these make the last rising part of the Hubbert curve before the peak. First we squeeze the last capacity and then we peak.

But it was really the demand that caused all this. Where did it come from? China, of course. The driving force is the Chinese coal production that is growing at 10% level every year. This makes the unprecedented Chinese economic growth possible. This growth is the real engine of the world economy now. But the Chinese energy mix is unbalanced because 70% of it is coal. This causes the relentless demand for oil.

Now we see why the oil prices will not go down to the “reasonable” 30-35$ level and why the oil has not peaked yet. The price has not really signalled the coming peak and the production growth has not signalled that the peak will not come. We may have still a couple of years left to the real peak. Nobody can exactly predict the timing and we will have this discussion going on for some time, and quite likely after the actual peaking. It will not be easy to see and many events, a recession, political disturbances, hurricanes and so on can mask it.

My point in bringing up the stripper wells is simply to emphasize that the doom and gloomers are in my mind warping this conversation about peak oil as much as the “bottomless well” cornucopians. When considering any issue, one has to consider one’s terms carefully. E.g. what do we mean when we say “the long-run.” Will the world be a much different place in 2100? You bet. And anyone who thinks they can make a prediction on what it will be is more than welcome to produce their particular variant of science fiction.

In the interim (which also must be defined), I think a very strong argument can be made that exconomics–price, some regulation, increase development–can help society to roll over the peak and pass through the bottle neck (see latest scientific american on the discussion of bottleneck–a bit fluffy and light but still worth the small amount of time to read:

http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?chanID=sa006&colID=1&articleID=00031010-F7DA-1304-B72683414B7F0000

)

And I do agree with the poster who said that tourism is a big industry. It is. Again, it’s a matter of how we deal with the transition. Is it really necessary for people to be flying all over the world? Are people’s live’s so locally empty, are they so unable to buy a table top book, that they need to book a tour to far off places? There was a study done. Tourists got off a bus, went into the museum, bought a table top book, and returned to the bus. That’s depth of their “visit” to that particular museum.

So the transition is important. JDH has mentioned that. The transition to what? Who knows. Perhaps that’s the 2100 science fiction novel question. Lots of hypothesis. Sound minds have been considering those issues for a long time. Particularly since the 1960s. Tomes have been written. Great ones.

It all comes down to (1) physics (2) economics, including human psychology and regulation and (3) politics–lots of human psychology. That’s it. What are the limits placed by science? What are the economic implications? What policies should be put in place? What are the political issues and chances of getting those policies in place?

The focus, and the only place where I think productive work can be made–productive work that might, just might affect politics–is to model this issue as best as possible. I’ve long thought that a combined economic model with the sort of end-of-growth world models that were produced (and are continally refined) would help us better understand how this will play out. And help define policies, if any, to smooth the transition.

A recent study, Fuel Ethanol Cannot Relieve US Dependence on Petroleum, places the ethanol energy balance in the US at 1.1:1, while in Brasil it is 3.7:1. Processes and technology will be important but efficiency will probably remain more so.

Joao –

Basic economic assumptions support your position that there will not be exploration or production from non-profitable fields – except –

When there is a wide divergence of opinion, i.e., the price of oil for the next ten years, and when some conclude that there will be $100 oil this year with only minor easing, more money will be invested in exploration, whether from the coffers of the major oil producers, or from individual investors.

Once a well has been drilled, the decision to cap, abandon, or produce is not based upon drilling cost + completion costs (pumping equipment, pipelines, etc), rather it is prospective income compared to completion cost alone. Accordingly, more capital spent on drilling will produce more oil, even though some of it will not be cost effective and will not produce profits compared to the total investment.

The basic hypothesis is that the gas price increases resulting from refinery shutdowns due to Katrina will give a distorted view of oil economics to investors new to the field with the result that there will be an unwarranted diversion of capital. The longer gasoline prices (and natural gas prices) remain at current levels, the more severe the distortion.

Investors are always irrational in the short term. In the long term, economic forces eliminate those that were both irrational and wrong.

Bill

The situation in the Gulf, as of today:

http://www.mms.gov/ooc/press/2005/press0906.htm

What’s the price estimate and elasticity here? CERA can’t have it both ways.

If oil stays at $70 because demand is highly inelastic, then CERA may be half right: LOTS of new production will come on line, and new investments will continue to be made, delaying the peak. But the price won’t collapse to $25.

If oil collapses to $25, then CERA will be half right: right about the price, but the low price will depress investment and mean that supply will grow much more slowly – an earlier peak. This case would also require substantial demand destruction and global economic pain.

But you can’t have a sub-$50 price AND large increases in future production. The economics don’t work. And if CERA *is* right that we will have both massive investment and supply growth coupled with a collapse in oil prices to $25, that implies a TOTAL market failure in the near future on the order of the 1998 oil price collapse!

… in which case we should not be so confident about the ability of the market to correctly determine our energy future.

“I’ve long thought that a combined economic model with the sort of end-of-growth world models that were produced (and are continally refined) would help us better understand how this will play out. And help define policies, if any, to smooth the transition.”

That’s right. But I don’t know any “theory of negative economic growth” in the same sense as we speak about “a theory of economic growth”. Negative growth is considered an anomalous, temporary and negative phenomenon. But we may have to live with it a long time in the near future. So we need a real theory on that. We have some empirical data, dying communities and regions and the economic collapse in Eastern Europe. This data should be analyzed from a new viewpoint.

We need also a theory and empirical research on negative population growth. This is a real phenomenon in many Eastern European countries. Diminishing population is nowhere a governement policy, on the contrary. But they still have a population diminishing by 0.5% a year. And the cause is mainly a very low birth rate. The population control programs in China and India are basically failures compared to these Eastern European countries (some of them are Catholic). It would be very important to understand this.

Bill: “Accordingly, more capital spent on drilling will produce more oil.” Only if there is oil. No capital will produce oil from dry wells.

Silent E: “But you can’t have a sub-$50 price AND large increases in future production.” Yes, but we have had this before. Production once started will not be shut down easily. There is the time factor and the need to get some income from the initial investments. The fault of CERA is not here. It is more in the geological sphere.

TI: I agree on Eastern Europe. And Russia might be a good example. They’ve taken a huge hit in GDP. Though it’s probably difficult to trust any numbers that came out of that place.

And I also agree that negative growth must be considered. Though I suspect we’d see something more like cycles of growth and recession. But you do raise a good point.

::::::::

A recent study, Fuel Ethanol Cannot Relieve US Dependence on Petroleum, places the ethanol energy balance in the US at 1.1:1, while in Brasil it is 3.7:1. Processes and technology will be important but efficiency will probably remain more so.

:::::::::

Lord – I agree having worked as a chem engineer in a US fuel ethanol plant in the heart of the US Midwest… But understand the thermodynamics of Brazil (cane) and the US (corn) are very similar… both convert starch (corn) or simple sugar (cane) into ethanol & ferment them into ethanol… the only ‘thermodynamic’ difference is in corn you have to convert the starch into fermentable sugar before it can be fermented… since starch is nothing more than a chain of sugars it isn’t difficult at all – is but capital intensive.

The economics of the two really do come down to ‘process’… how each is done & how costly the inputs are for each… primarily capital vs labor. Also the alternative values of each…which has more value as food vs fuel.

Having said that… the way we do it in now in the uS via corn… I think the 1.1:1 ratio might be ‘OPTIMISTIC’ …it really depends on how far out you draw the ‘system boundaries’ and what ‘processes’ you include in calculating the balances… If you consider the plowing, planting, chem application, cultivation, harvesting, drying, & transporting of corn in that energy balance ratio… I think it would have to be negaive… at least as we do it today.

UNLESS ethanol production is considered to be a form of ‘energy arbitrage’ where coal is used to power the ethanol plants so that the an ethanol plant really becomes more of a synfuels plant converting coal energy to liquid ethanol fuel through fermentation of corn & distillation (powered by coal generated steam)… unless it is looked at that way, then turning food into fuel is a loser all the way around.

They need to develop better crops for bio-mass feedstock… ones generating a lot of easily converted bio-mass per acre… Plus develop processes that can digest & ferment ligno-cellulose as well as starch & sugars and do it economically (efficiently & fast).

Possible but it isn’t there yet…

In the long run corn & soybeans are both dead ends for energy production… there is no way to ever make them sufficiently ‘efficient’ to offset their alternative intrinsic value as a food source.

dryfly:

Familiar with Algal Biodiesel?

http://www.unh.edu/p2/biodiesel/article_alge.html

Theoretically, 10-20,000 gallons of the stuff per acre/year, compared to 50 for soybeans.

Hey Donny!

So “Most of them [oil tankers] can move around 30-40 knots.”

According to this, the Exxon Valdez can do 16.25 knots:

http://www.nationmaster.com/encyclopedia/Exxon-Valdez

LNG tankers run a bit faster at 20 knots since their cargo is boiling off as they run.

30 knots is good for a warship but rare for a merchant ship (the USS United States, one of the last passenger liners did 32 knots). 40 knots is really fast, except for a nuclear submarine underwater which can do maybe 45 or 50 knots.

DryFly and Joao:

Does the equitorial location of Brazil with its milder, year-round climate and increased insolation make a difference in their success with cane vs. our experience with corn?

dryfly,

There are important differences between sugarcane and corn as feedstock for ethanol production. Most importantly, sugarcane mills use bagasse (what’s left of the plant after the “juice” has been extracted) as energy source – in Brazil most are self-sufficient and some even sell electricity to the grid. Furthermore, over the thirty years several technological advances have been made in the production of sugarcane – yield and sugar concentration have increased substantially. Transportation, once an hindrance for large scale production, has been addressed by means of long compositions (24 or more wheels).

Back into the issue here, I was caught by CERA’s prediction of an increase in production of the (very mature) Marlin field in 2010. Anybody knows why?

Ethanol is not really a practical fuel in the United States. Its energy density is only 2/3 of gasoline, and corn alone cannot provide even a significant fraction. I have read about new production techniques that can turn cellulose into ethanol, which raises the energy balance signifcantly. But farming corn by itself is not the answer.

Algal biodiesel has vast potential, IMO. However, whether it will be commercially viable is still an unknown. There are two production techniques that I know of: 1) raceway brine or wastewater ponds, and 2) a closed system that uses coal power plant flue gasses and grows the algae in clear plastic tubes.

http://www.greenfuelonline.com/

From my own research, I think biodiesel has the most potential of all alternative fuels out there. Diesel engines were invented to run on plant oils, and biodiesel can be mixed with petrodiesel in any amount.

I really hope that the CERA estimates are true. But I note that as time goes on, a significant fraction of oil is coming from unconventional sources. I’ve read some claims from someone in the oil industry that these sources require so much infrastructure that they can’t possibly take up the slack as the easy oil declines.

Cerqueira

I am familiar with bagasse… corn plants don’t have it or rather ‘leave it in the field’…

However the big efficient North American corn mills have co-gen units that burn coal… the high pressure steam produced in the co-gen units drive turbines producing electricity and the low pressure steam exiting the turbines is used for processing in the mill – distillation of the alcohol, evaporation of the stillage and drying the feed. The excess electricity produced is sold into the grid. So two energy products are produced PLUS lots of animal feed.

As a result the total efficiencies are far better than many realize… but the capital cost is staggering… far greater than a cane mill.

:::::

JonBuck – I’ve heard of it and downloaded their paper but haven’t read all of it. The criticism I’m hearing is that it is VERY dificult to grow one strain of algae in an efficient & continuous manner… contamination from other strains raises havoc. I would guess that is true… where I worked we ran continuous fermenters (obviously yeast not algea)… But had contamination issues as well. it was a pain to get it ‘clean’ again after contaminated.

But in the long run this will be the kind of solution we will have… whether algea, or poplar trees, or elephant grass, or some new hybrid cane, or hemp, something that produced tons of bio-mass per acre… is easily processed, both simple sugars & ligno-cellulose materials… but we are not there yet.

:::::

Joseph Somsel – I think the equatorial vs temporate zones each have their issues & benefits. Certainly longer growing seasons in the tropics but far fewer pests in the temporal regions. It is amazing how a very hard winter reduces pest damage the next year.

The key isn’t to do ONE solution everywhere but rather tailor the solutions to the market & the location… no more one-size-fits all.

There are a lot of discussion about biofuels as a solution to decreasing oil production. Most of the people participating simply dont’t understand the scale of the problem. It is not enough to point out that the technology is there. The farmland to produce needed quantities of biofuel is simply not there. Remember that it is only the net energy gain that counts – in order to make 100% biofuel you must produce from biomass also all the energy that goes into making biofuels.

In Brazil the fuel ethanol is a by-product of sugar production. The net energy gain must be calculated including both sugar and ethanol.

The alternatives discussion misses the point of fossile fuels depletion completely. Almost all other people in the world make it with far less energy use per capita than the Americans. Look at the ASPO basic scenario (www.peakoil.net, the curve is in every ASPO newsletter) – everybody should look that. The oil is not going to end. For Americans it means that they will have to return to the consumption level of ’60s or ’50s. Not so horrible. Besides, there is a lot of time for it, several decades. For the rest of the world it is more difficult. They will not get the economic growth they expected, things will get worse.

That is why we need research on sustained negative economic growth. Because that is what we will get.

This is after all Econbrowser, not Oil Drum or some other Peak Oil blog. I think this is a place to discuss about economic policy in a situation of diminishing energy supply.

Me: “But you can’t have a sub-$50 price AND large increases in future production.”

TI: Yes, but we have had this before. Production once started will not be shut down easily. There is the time factor and the need to get some income from the initial investments. The fault of CERA is not here. It is more in the geological sphere.

====

I agree that it has happened before – but it happened as a result of an unexpected recession that caught the market by surprise and led to huge losses for the oil companies.

But CERA is making a forecast: how much oil will be developed for production each year over the next two decades, and what the likely price will be. They have to assume that market participants will make rational decisions to develop production while avoiding a loss-making market collapse.

After all, if CERA is right that there is going to be a glut in five years time that drives prices to $25, why would any oil company approve new projects now that rely on $40 or $50 oil for profitability? If CERA is indeed making an assumption that there will be a money-losing glut, I hope they’d at least include that fact in a footnote. I don’t think you can do market projections like CERA’s and depend on the stupidity of oil executives for your rosy results.

I’ll add that CERA’s press release on the report states the following:

Supply balance — The balance of supply over demand has the potential to expand significantly over the next five years, and this could drive oil prices to the downside. If demand growth averages a relatively strong 2.2% through 2010, prices could weaken from recent record highs and slip well below $40/bbl as 2007-08 nears. If demand growth were notably weaker, a steeper price fall would be conceivable; however such a fall would likely slow capacity expansion and bring a market rebalance within two to three years.

=====

But what are the price expectations for those projects? Are they $40/bbl, or lower? Do oil companies PLAN on losing money in a recession? Does CERA assume that they will chose to do so?

CERA’s analysis doesn’t appear to take into account the information that oil companies get from potentially falling prices: “don’t drill!” If there’s a strong possibility that prices will fall to $30, no company will develop $40 fields. That hints at another important question: what are the projected amounts of new production at each price point?

I think that the production decisions of the oil companies are quite complicated. Oil projects take a long time to complete and when they are online they go on producing even if the price environment changes. Those projects listed by CERA abd ODAC will go on anyway.

Besides, most companies are national and they follow national strategies. The technology pushes deveopment, too: when for instance ultra deep-water drilling equipment and methods become available and the initial costs are paid, new deep-water projects will follow.

The oil companies do of course react to prices, but in a complex way. But the problem with CERA is what we began with: it is clearly over-optimistic and under-estimates depletion. Oil production is extraction, the geological factors are important.

CERA and ODAC list basically the same projects but interpret the total situation diffrently. Some of the listed projects are now online but the prices have not gone down. The prices are volatile and the trend is still up. The pessimists say that the production will peak virtually today. We’ll see. ASPO gives us 2 more years, until the growth potential of these new projects are exhausted. But now we have more evidence that the Saudis don’t have other spare capacity than heavy sour. Russia has been producing flat for several months. There is nothing much growth potential left. But we’ll see.

Are you sure no one wants them in their backyard?

You may have heard some claim a lack of refining capacity is driving up fuel costs. They usually mention in the same breath that . Recently there has been a temporarily spike in gas prices due to limited refining capacity…

“Research on negative economic growth”

For a good case study, read Gibbon’s “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.” The economics are scattered here and there, including political interventions much like Lockyer’s. It’s also illuminating to see a plot of European climate over the time period. The rise of Rome coincides with a period of warming temperatures so that wine grapes were grown in England (can’t do that today). The contraction of Roman power and wealth also coincides with a cooling trend.

For another case study, look at the Ottoman Empire – I’d look to Bernard Lewis.

For more pure economics, perhaps the good Professor can provide a recommended read list on negative economic growth.

Dryfly:

According to Dr. Micheal Briggs, who wrote that UNH study that I referenced, closed “bioreactor” systems for growing algae do not suffer from the contamination problems that open ponds do. But the fact remains that this production method has yet to be tested on a commercial scale.

I hope they succeed.

Joseph: the fall of the Roman empire was not a case of negative per capita real growth. There are some historical estimates of GDP per capita and they show that GDP per capita in fact grew a little after the Roman empire had collapsed. There was no real growth during the Roman time because they did not use fossile fuels (in any significant scale).

Real per capita negative growth is not same as collapsing society. The fact is that we now consider a 2 – 3% per capita real GDP growth as normal state, 0 – 1% is already a recession. But this has been the case only the last 100 year or so. In the beginnining of industralization the growt rate was 0.5 – 1.5%. Before that it was around zero (-0.1 – +0.1%). Population growth brought absolute, aggregate growth but very slow per capita growth.

Now we see that as the present growth is a relatively new and unprecedent phenomenon, a negative per capita growth of -1 – -3% or more will also be quite unprecedented in the modern world. We have some short time experience of this (some depressions) but no experience of this going on for many years (10+). It is quite likely we will get this after the peaking of oil and total fossile energy production.

Where is there a more sophisticated discussion? Listening to idiots here who think that Cali can have $2.00 gas (without lines, rationing) is depressing. I know there is lots I can learn (game theory, geology, long term capital budgeting, options valuation, government policies, etc.), but instead here I listen to people who who don’t even know the very first day lecture of a freshman micro course…who don’t even know the nature of their ignorance…who think it is somehow “political” to explain basic supply and demand! sheesh.

How does a full up college professor stand it?

TCO, people with different training and backgrounds can often come at a question with very different perspectives, and there’s often something to be learned from trying to see how the situation looks from the other side. I do believe that economists can get too comfortable with our framework for evaluating questions, and think it’s a very healthy thing to try to explore the basis for these assumptions with someone who is quite skeptical about our whole approach.

One thing I’m confident about is that, although my readers have a variety of different backgrounds, they are not stupid.

By the way, I’ve also appreciated your insights in comments on previous threads and think they’ve added a lot.

Thanks for a kind answer to me and to those I insulted. You da man.

[repeating self, sorry]I think there is a value in questioning assumptions and frameworks, but (generally) less of one from people who haven’t even bothered to understand the “orthodox religion” before nailing theses on doors. IOW, sure if someone here wants to take Mansfield apart after having understood it, great. But if they don’t even know how to draw supply and demand curves and then “think they know better”…well that is like people who blather in physics threads about how “quantum mechanics has to be wrong…it doesn’t make sense…yada yada”, when they don’t even know the first thing about it.*[/repeating self, sorry]

I should stay away from the net. I find it intellectually (and in some ways socially) exciting. But I get way too agressive on it. And I need to find some things in my daily life to supply that type of stimulation. (Suggestions?)

*Sometimes a really thoughtful person who is new to a field can (withought knowing the full buildup of the field) still question some postulates or have some general insights that drive the thinking…and I don’t approve of shushing such a person because of not having done some arbitrary pre-work (this is basically where I’d like to find myself! My “training” is very sketchy.)…however I don’t generally find that to be the case here.

TI,

Gibbon makes a good story of how the wealth and prosperity of the Roman citizens declined after its peak around 50 to 150 AD. He describes exploitive and counterproductive tax policies, price controls, currency devaluations, changes in land tenure, trade disruptions. After the fall in the West, population densities certainly fell which might have increased per capita incomes.

The Roman per capita growth came from wider use of wind and water, broader trade, peace and security (fewer hungry troops per capita to feed), good government, and maybe imported slaves – the latter subject to debate.

Of course, modern scholarship may have better figures and a more comprehensive story – Gobbon wrote about the time of the American Revolution. Perhaps you could offer some references?

As to the Ottoman, Bernard Lewis discusses how in the 1500’s, England had more windmills and water wheels that did all of the Ottoman empire – these are fixed assets easily traced in tax records. Hence, the Ottomans fell behind in energy production setting the stage for their eventual contraction.

As to your data on growth rates, I agree. human economy depends on energy and prior to the industrial revolution, almost all came from solar photosynthesis (except the above mentioned windmills and water wheels.). Any per capita growth came from better agricultural methods, infrastructure improvements (increased knowledge being one) or increased trade (see Romans above). Again, England was an earlier leader in more productive agriculture too,

Economic growth is closely tied to increased energy use and its productive use. Note I differentiate from “efficiency” – electrification was productive while not necessarily efficient of energy. One result of peak oil and peak gas will be increased incentives to further electrify.

Professor,

Yes, different viewpoints, if not smart (most are), at least revealing.

Here you have an historical estimate of world GDP: http://www.j-bradford-delong.net/TCEH/1998_Draft/World_GDP/Estimating_World_GDP.html

Of course this is for the whole world, not just the Roman empire. The Roman empire had of course visible economic development and rising living standards – but probably mostly for Rome and other cities. Concentration of wealth is not economic growth.

DeLongs series show quite convincingly that there no significant economic growth before the industrial (fossile fuel) age. If there were periods of 0.1% yearly GDP per capita growth that cannot be compared with present world growth rates. The population growth was also very slow compared to the present rate. The renewable energy sources don’t really grow. You can only take a little bigger share of them, if possible. That is why renewables-based economy hasn’t virtually any long term growth.

That makes the point for the energy efficiency discussion: in the long run societies optimize their energy usage and there is no growth any more based on increasing efficiency.

There was no real economic growth theory before the 20th century – it is mostly from the ’50s and ’60s when the oil-based growth reached an unprecedented rate. Now it is quite clear that we shall have a theory of protracted economic contraction – when we start having negative growth of 1 – 5% a year. This will also be a new phenomenon. Renewables-based economies may have wide fluctuations (the biomass people should remember this) and natural catastrophes, with sometimes permanent damage, but they don’t have prolonged contraction.

One per cent negative growth means deep recession., unemployment and lacking investments. If this goes on for 5 years it is already a depression.

Much of the discussion about curbing oil usage centres on private driving. It seems easy to cut fuel consumption by 5% there, but that is not the whole story. Only 70% of oil goes in transportation (in the US), and only a part of that is private use. In fact to cut overall oil consumption by 5% by diminishing private personal transportation use you have to cut that by almost 10%. The probable depletion rate after the peak production could well be 4-5% or more. Even if the private transportation use could be cut that much it will have large cumulative effects for the rest of the economy. If we cut oil consumption all over the board it will hurt all parts of the economy. This is the problem.

What should be done? To learn to accept these facts. Many of the people speaking of the Peak Oil seem to think that the main task should be to find some way (technology) to continue like before. I think we should have a realistic picture of the future and try to understand the coming changes in order to manage them.

“manage them” = let the price mechanism create demand reduction naturally? Or “manage them” = government programs? Are you perhaps a light rail investor? 😉

TI,

Great post and link. I’m digesting it now so I’ll get back to you.

I would note that Malthus wrote about a largely renewable energy economy. Today, he’s largely discounted but I think that unjust – fossil energy changed the equations temporarily. Perhaps his analysis will again be applicable to post-peak economies.

I’ve often noted that the rise and fall of pre-industrial civilizations coincided with changes in climate. It takes excess energy to mount a war of aggression and that only comes when food production outruns population growth, a transient event in Malthusian economics. (See comment above about climate and Romans.) A change in climate that increased grassland productivity in the steppes of Asia would give the Mongols an edge, for example.

That may also be why “hydraulic civilizations” per Wittfogel and the most stable. Well founded irrigation systems greatly increased productivity and stablity let the accumulation of knowledge provide additional positive economic feedback.

As to the future, I’m not as pessimistic as many. There are lower EROEI backstops to oil that will suck up much capital in the next few decades, leaving little for other investments. Put me in the “buckle down and do it” category.

Where is the “if it’s going to happen, it will happen” category?

TI,

A detailed reading of the link shows that they assume constant per capita income a priori and work from there.

I think a reading of history shows that there are good times and there are bad times. Even the Bible talks about “seven fat years and seven lean years” or something like that.

I suspect that in pre-industrial ages, the best times were of a combination of climate warming and good government. For example, the High Midevail Period (1000 to 1300 AD) saw a flowering in Northern Europe with warmer temperatures while the Religious Wars that followed had a cooling trend.