Do recent energy shocks mean we might see a replay of the 1970’s stagflation? I believe not, and here’s why.

The term “stagflation” was introduced in the 1970’s when the economy simultaneously experienced stagnation of real output growth and an acceleration of inflation. Recent spikes in energy prices have led some to worry about whether we might again find use for this nasty term, with

Capital Spectator, William Polley,

the Oil Drum,

My Left Wing, and

Simply Apalling among the many discussing this concern during the past few weeks.

By “inflation” we refer to a condition in which the dollar price of most goods and services is rising. It is equally accurate to describe it as a condition in which the quantity of goods and services that you can buy with one dollar is falling. It is certainly nonsensical to propose a theory of inflation that makes no reference to the quantity of dollars that are in circulation.

At any point in time, we can measure the total quantity of assets that people hold that can be used directly to pay for purchases. Chief among these would be currency and balances such as checking accounts. This measure is known as the money supply. There are some assets whose categorization might be somewhat ambiguous. Savings accounts, for example, may function very similarly to checking accounts even if you cannot pay for transactions with them directly. These ambiguities give rise to alternative practical measures of the money supply, such as “M1” which excludes savings accounts and “M2” which includes them. Given a measure, we define the total quantity of the asset that the public wants to hold as “money demand.” Money demand would be a function of variables such as the level of real GDP (Y), the overall level of prices (P), the nominal interest rate (i), and other factors (v):

Students sometimes find this notion of “money demand” to be a little confusing, in that you might think that you “demand” all the money there is. But the idea is really no different from talking about the demand for any other item of value. You might have said that you “demand” a 10,000-square-foot house, but not, it turns out, if you actually have to pay for it. Similarly, the economic notion of money demand is that if you want to maintain a higher balance in your checking account, you’ll have to sell off some other asset or forego some purchases. Given your reluctance or limited ability to do so, there is indeed some finite level of money balances that you would choose to maintain.

We expect from economic theory that the elasticity of money demand with respect to either of the first two arguments should be about unity. If you plan on buying twice as much in the way of real goods and services (Y twice as big), you’ll probably want to maintain about twice as big a balance in your checking account (m twice as big). Or, if everything costs twice as much (P twice as big with Y the same), you’d again likely want twice as large a value for m.

The government can control the total supply of money (the quantity of M that’s available) fairly directly. Dollar bills only get into circulation when the government prints them, and dollar checking accounts are regulated in a way that allows the Federal Reserve to direct their total to any desired amount by changing the quantity of reserves (electronic credits for dollar bills) that the Fed itself issues. When the government changes the money supply (M), the variables that influence money demand (Y,P,i,v) must adjust in order to keep money supply (M) equal to money demand (m).

Given a value that the government sets for M, it is also clear from the above equation that a change in Y, i, or v could cause inflation (an increase in P). However, the potential of changes in a variable like real output (Y) to affect inflation are inherently pretty limited. Given the near-unit elasticities, if output were to fall by 2% (meaning m would decline by 2%), if the government did not change the money supply M, equilibrium in the money market could be restored with a rise in P of 2%, i.e., 2% inflation. A 2% drop in real output would be a quite dramatic and unusual event, but, even so, we have just seen that the repercussions for inflation should be relatively minor. On the other hand, there is no fundamental limit on how much the government could increase the money supply M. If it increases the money supply by 50%, the natural way that money market equilibrium would be maintained is with a 50% increase in prices (50% inflation). Very high, sustained rates of inflation would be almost impossible to arise as a result of changes in Y,i, or v, but are very easily produced as a result of an increase in the money supply of the same magnitude.

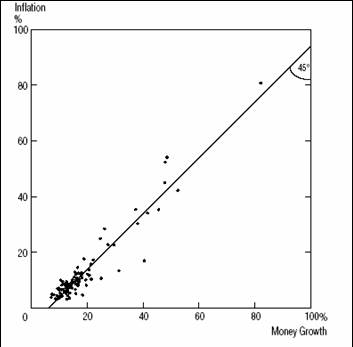

The graph at the right is taken from a study of 110 different countries by George McCandless and Warren Weber. Each dot summarizes the data for a single country. The height of the dot measures the average rate of inflation in that country during 1960-1990, whereas the horizontal coordinate corresponds to the average rate of growth of the money supply (as measured by M2) for that country. The theory sketched above would lead us to expect to see these dots fall along a line with a slope of 45 degrees, which indeed is pretty much the case. No country ever experiences double-digit inflation over many years unless the government has caused its money supply to increase at double-digit rates.

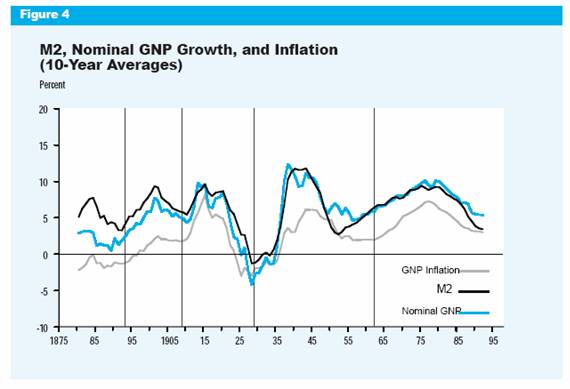

You can also find something similar when you look at data for an individual country such as the United States over a long enough period of time. The above graph comes from a paper by William Dewald which plots the average growth rate of U.S. M2 over 10-year periods compared with the average inflation rates and growth rates of nominal GNP. Surges in inflation in World War I, World War II, and the early 1970’s all coincided with surges in money growth rates. U.S. M2 has grown at a 6% annual rate over the last 10 years, which, with 3-1/2 percent annual real output growth, would be consistent with an inflation rate around 2-1/2 percent.

There are many things we do not understand perfectly in macroeconomics, but how to make inflation is not one of them. If you want a high inflation rate, I guarantee I can develop a government policy to deliver it, namely, print enough money at a fast enough rate. Conversely, if the government refrains from doing this, there is no way that we’re going to see enormous rates of inflation.

Although this simple story of inflation does pretty well over broad periods, it’s next to useless for purposes of predicting small changes in inflation on a year-to-year basis. This is because if the question you want to ask is whether U.S. inflation over the next year is going to be 2% or 3%, the other factors in the above equation (changes in Y, i, or v) are going to make all the difference. Although in the absence of rapid growth in the money supply, supply shocks could never produce sustained double digit inflation, the energy disruptions of 2005 nevertheless could easily lead to a temporary, modest rise in inflation, through two channels.

The first is the one mentioned earlier. To the extent that the energy shocks lower potential output, for given values of the other variables, that would mean higher inflation. Now, one might argue on the basis of the above equation that the Federal Reserve could counteract this simply enough by reducing the money supply M correspondingly. In my view, however, this would be a mistake. The reason is that one way in which the energy shocks are likely to lower output is by idling capital and labor. Lowering the money supply M is surely going to aggravate this tendency, and the lost output is a deadweight loss that is not benefitting anybody.

A second reason why the recent energy price shocks are likely to produce a temporary increase in inflation can be seen by looking at the distribution of price changes over the last year. The above histogram (more here) shows how much inflation there was in different expenditure categories of the CPI last year. The lonely pole at the right records the fact that gasoline prices had gone up over 30% as of August; we’ll doubtless see an even more impressive outlier when the September data are added in a few days. Fuel costs receive a weight of about 4% in the CPI, and primarily reflect a change in relative prices (gasoline has become more valuable relative to potatoes) rather than inflation (a dollar is less valuable relative to potatoes). This change in relative prices is something that the Federal Reserve has very little power to change or influence. Suppose that the Fed wanted to make sure that the CPI only increased 1% in such a setting, despite the 30% increase in the relative price of fuel. The only way this could be achieved is with a 0.2% decrease in the average price of everything except gasoline,

in other words, the Fed would have to force the rest of the economy into deflation. This is something it has the power to do, but again is something that is usually accompanied by substantial wasted resources and lost output.

It makes far more sense for the Fed to go ahead and allow the energy price increases to result in a temporary and modest increase in inflation in order to try to make sure that the output costs are also temporary and modest. As long as this is strictly a temporary relaxation of its inflation target, there is no reason that this need have any implications at all for the Fed’s long-run commitment to low inflation. Indeed, the low yields on long-term Treasuries suggest that the market has very little concern about this at the moment.

But isn’t a simultaneous slowdown in output growth and increase in inflation exactly what we’re talking about with this dreaded “stagflation” term? Yes indeed. But if we were to succeed in keeping both effects small and temporary, there’s not so much to dread. The goal is to make sure that neither effect gets out of hand. And at the moment, my bigger concerns are about the output side of the equation.

Prof: Great stuff… That inflation is caused by increase in the supply of money is a big part of the equation.

A few lay thoughts:

Inflation does not matter; only relative prices matter. The American standard of living depends on productivity, not inflation per se. When productivity rises, there is more output to be divided. Wages are the largest cost of production. It is difficult to reduce prices without falling wages. (During the Great Depression, nominal wages fell with prices but real wages did not fall.)

I’m inclined to agree that we won’t see the wage-price inflationary spiral of the 70s. For one, Globalism has put downward pressure on wages. On the other hand, commodities are putting serious pressure on prices. Resource depletion may finally put us in a place we’ve never been before. I believe markets may not have an answer at the margins where the old reliable theories break down.

When I look at the graph correlating money supply growth versus inflation, it seems to me there’s a factor that’s not quite being addressed in your discussion. If there’s inflation, money is getting worth less. Therefore, everyone is going to tend to want to keep more of it in nominal terms, just to offset the inflation. So if the money supply in constant dollars is exactly flat, the growth in the money supply in nominal dollars will be exactly equal to the inflation rate. It seems to me this effect is likely to be the main explanation of the correlation in that graph – we are primarily just looking at the changing definition of what a $ (or a euro or a renmimbi) is, plotted against itself. It would be more interesting to explore the relationship between the constant dollar money supply and inflation.

I note that when you write M= m(Y,l,p,v), it’s extremely unlikely that these quantities actually have a relationship which satisfies the mathematical conditions to be a function (ie the LHS depends on the current values of the RHS variables, rather than depending in a complex way on the history). It seems to me that much reasoning in macro-economics is dubious because, while it superficially appears highly quantitative, it actually is depending on mathematical assumptions that are not even decent approximations.

It also seems to me your account of the money supply as being simply controlled by the fed is not a close approximation to the situation. The Wikipedia on “money supply” says:

“However in the 1970s the reserve requirements on deposits started to fall with the emergence of money market funds, which require no reserves. Then in the early 1990s, reserve requirements were dropped to zero on savings deposits, CDs, and Eurocurrency deposits. At present, reserve requirements apply only to “transactions deposits” – essentially checking accounts. The vast majority of funding sources used by banks to create loans have nothing to do with bank reserves.

These days, commercial and industrial loans are financed by issuing large denomination CDs. Money market deposits are largely used to lend to corporations who issue short term commercial paper. Consumer loans are also made using savings deposits which are not subject to reserve requirements. These loans can be bunched into securities and sold to somebody else, taking them off of the bank’s books.”

“The point is simple. Commercial, industrial and consumer loans no longer have any link to bank reserves. Since 1995, the volume of such loans has exploded, while bank reserves have declined.”

Isn’t the money supply primarily controlled by 1) companies and households desire to borrow, and 2) banks willingness to lend? Both of these factors are controlled in part, but by no means entirely, by interest rates.

It is really very difficult to see stagflation looming right now. The price pressures have been mostly deflationary. It is quite remarkable that the sharp rise in oil, natural gas and commodity prices has not caused significant inflation during the last couple of years.

We could attribute this, too, largely to the China effect. The energy prices have not affected China much because it relies mainly on domestic, price-regulated supply. Low overall costs and rates there have also helped considerably. The Fed policy has been mostly inflationary but ineffective in this sense.

A dollar crash could change this, but more probable would be an old fashioned deflationary recession.

Stuart, when you say that “everyone is going to tend to want to keep more [money] in nominal terms, just to offset the inflation”, I believe that you are saying exactly the same thing that I am, and that you are thinking precisely in terms of the unit elasticity of m with respect to P to which I refer. Specifically, if P goes up by 2% (2% inflation) then m goes up by 2% (people want to hold 2% more money). I believe we’re both thinking that this is exactly what the graph is showing, and I agree, it’s exactly what you’d expect to see when you think about this relationship.

As for the Fed being unable to control the money supply, I have to disagree with you. For starters, it is the Fed itself that sets these reserve requirements as one component of monetary policy. Furthermore, the quantity of bank loans is not the same thing as the money supply. The money supply measures the quantity of a certain class of assets held by the public. If you have a loan that you received from a bank, that is your liability, not your asset.

Finally, I do think that these are proper functions. A particular household takes Y, i, P, and v as given and chooses a value of money holdings that make sense in that environment. If one of the variables (such as P) were to change, we could ask how would the household’s choices change as a result. I believe that this is a perfectly well-posed question, and it is perfectly appropriate to represent the answer to this question with an equation, since both the variable that is being changed (P) and the variable on whose effects we wish to explore the consequences of that change (m) are quantitative.

Now, I agree that once you aggregate these behavioral equations across all consumers, and say that in equilibrium this summation of money demand m has to equal the quantity supplied by the Fed M, it no longer has the sort of left-hand right-hand interpretation to which you refer. That’s because the equation as written is really the combination of three separate equations, the first being the household money demand decision I just described (determines money demand m as a function of Y,P,i,v), the second being a description of the Fed’s behavior (determines money supply M as a function of Alan Greenspan’s latest notions), and the third being the equilibrium condition (money demand m must equal money supply M). Once you put the three together, the result M = m(Y,P,i,v) does not determine either the left side M or the right side m but instead describes a relation between Y,P,i, and v that has to hold in order to maintain money market equilibrium, and tells us how those variables would have to adjust if Greenspan changes M. I believe you’ll find that this is the mathematical sense in which I make use of the equation.

Stuart –

In times of inflation, those that hold cash denominated assets lose, and those that hold assets and debt, win. Twas the time that it was regarded as foolish to have money in the bank because inflation was severly eroding its value.

Over the last five years, the Euro has moved from eighty US cents to a dollar twenty, a 50% move. This roughly paralleled the move of oil from thirty dollars a barrel to forty five. Whether this is a devaluation of the dollar, or inflation in oil prices is simply a view point. Inflation is simply a readjustment of the relationship of asset values (and service values) to monetary units.

The economic problem of stagnation was previously explained by JDH to be an ineffective allocation/utilization of labor. Full employment requires a positive business outlook that requires a positive consumer outlook that requires a job. The relationship between the current price spike in oil, and the economic outlook is simply a product of the perception of consumers and business owners. It is when both get hyper conservative that the direction is changed.

Bill

JDH:

“If you have a loan that you received from a bank, that is you liability, not your asset”.

Yes, but if I owned a house with some equity in it, I could choose to borrow against that equity in order to create some more money in my checking account, which will then show up in M1. If I were running a company with some credit lines, I could choose to borrow more or less against them, which will also show up as changes in M1. Very often, households and companies that are feeling economic pain will react initially by borrowing more, provided they have the credit to do so. This will be especially true if nominal interest rates are low relative to inflation so the cost of that borrowing does not seem too high. The aggregate effects of all those decisions to borrow more increases the money supply. It seems to me that these effects are likely to be pretty substantial

Can you point to any empirical data or analysis that bears on this question?

Just because several variables are quantitative and have an effect on each other doesn’t imply there is a functional form. To use a function, we would like to be assured that if we move around in the RHS parameter space, whenever we come back to the same point in that space, the value of the LHS will be the same. The function needs to be single valued. If taking a significant excursion and then coming back would cause things to be different, then it isn’t a function. Eg a household, or an economy, that goes through a recession (a few percent decrease in Y), will not behave in the same way afterward. It will have been burned and be more cautious, and might, for example, insist on maintaining more money in it’s saving account(s) than it used to. Thus M2 no longer has the same value for a given value of Y that it used to, even after quite modest changes in Y. It’s in this sense that I don’t think it’s a function – the value of the LHS depends on the history of values of the RHS, not just the current values.

How do dollars held overseas by foreigners figure into this? One of the odd things about this business cycle is that because of overseas production and the housing boom, credit expansion here has sent a lot of dollars overseas (low interest rates encourage housing refis instead of domestic investment, the purchases go towards goods produced overseas).

1. Doesn’t the fed have to worry about those dollars returning when foreigners’ desire to hold them goes down?

2. Might there be a bigger lag in a global economy than in a national one between credit expansion and inflation? Dollars sent to china have to rattle through a fairly clunky exchange regime before they end up affecting prices here.

3. Couldn’t inflation in things like fixed income instruments and oil show up before inflation in, say, american cars because the overseas recipients of those dollars seem to want to purchase bonds and oil more than american consumer goods?

Stuart, any time that a bank credits you additional funds in a checking account, it is required to hold a certain amount of funds (called reserves) in a separate account with the Federal Reserve. The Fed doesn’t give them these reserves just because the bank made a loan or has collateral. Your bank basically had to get the reserves from another bank, which loss of reserves would reduce its ability to create checking accounts.

What happened in 2002-2003 was that the Fed created lots of reserves, too many in my opinion, so that banks were able to create lots of checking accounts and loans were offered at very low rates. Now that the Fed is tightening, interest rates are headed up.

But there is no question that the Federal Reserve controls the total quantity of reserves, and can create them or destroy them at will. This creation or destruction causes the money supply to expand or contract.

JDH:

So why doesn’t the Wikipedia seem to agree with you? Again:

“The vast majority of funding sources used by banks to create loans have nothing to do with bank reserves.

These days, commercial and industrial loans are financed by issuing large denomination CDs. Money market deposits are largely used to lend to corporations who issue short term commercial paper. Consumer loans are also made using savings deposits which are not subject to reserve requirements. These loans can be bunched into securities and sold to somebody else, taking them off of the bank’s books.”

“The point is simple. Commercial, industrial and consumer loans no longer have any link to bank reserves. Since 1995, the volume of such loans has exploded, while bank reserves have declined.”

Anon, you raise a number of tricky issues here. First, just because a U.S. resident buys something made overseas, that doesn’t mean that the dollars have gone abroad. The importer perhaps received payment by accepting a deposit in an account it holds with a U.S. bank. It then could have done any of a number of things with those dollars, such as ask the bank to convert them to yen which it then withdraws.

There is an issue with U.S. currency, which can physically move out of the country and be used in transactions completely out of the U.S. To the extent that this occurs, it is a source of measurement error in the above equation, in that the M that the Fed has created is not the same as the m held by U.S. residents. You’re entirely correct that if these physical dollars came flooding back into the U.S., that could produce inflation without the Fed changing anything. However, were this to happen, the Fed would always have the power to reduce the domestic M in response so as to keep the price level from going up.

Stuart, I’m not talking about controlling the supply of loans, I’m talking about controlling the supply of money. They are two different things. Money is an asset of the public and loans are a liability of the public. They are two different concepts and two different numbers.

That a shrinking money supply will tend away from inflation of course seems generally right from a pure theoretical view.

What I don’t understand is how, over the medium to long term, the money supply can, from a policy let alone political standpoint, be permitted to shrink (or not to grow a lot) given the level of debt loads and low savings rates in the US.

Debt, without the globally competitive capacity to pay it off without giant stress on the US standard of living, is the biggest problem right now.

Stagflation, if it comes, will likely be the result of a falling dollar in a highly import-heavy economy.

When the dollar is not allowed to float freely but enjoys artificial support as in the current situation, markets are not allowed to work and adjust as they should in a slow and less painful way. Stagflation will happen because economic shifts to more competetive areas will not have taken place, so industry will sit uncompetitive, but there will be less support for the dollar, rendering imports much more expensive, with all the pass-through that may engender.

JDH:

But your argument to why households and firms can’t increase the money supply by just taking out loans and putting the proceeds in their checking accounts was that that would cause banks to need more reserves than the Fed will allow them. Or did I misunderstand you?

So the (alleged by Wikipedia) fact that the ability of banks to loan money is fairly decoupled from their reserves seems to directly undercut the logic of your position. Or am I missing something?

JDH, Stuart:

Even if the narrower measures of the money supply, M1, M2, etc. are under Fed control, it doesn’t follow that there isn’t a potentially dangerous credit bubble which the Fed would have no way to deflate gradually.

I suspect a lot of banks and other financial institutions are polishing their balance sheets by offloading credit risk onto counterparties who may or may not be able to bear losses in a crisis.

The market for credit derivatives has grown spectacularly and with poorly defined risk management processes (hence the recent effort by the Counterparty Risk Management Policy Group to tighten these up).

The Fed can choose to ratchet up reserve requirements, but it isn’t clear the banks the Fed regulates aren’t already below the existing requirements through use of credit derivatives.

To my mind this is the single greatest source of systemic risk — the sort of thing that could precipitate a real “hard landing” for the US/World economy.

“Money is an asset of the public and loans are a liability of the public.”

In accounting, a transaction has a debit side and a credit side. If I’m a company and I borrow $1m and put the money in the corporate checking account, I create a transaction which increases my asset checking account by 1m, and also increases my liability account with my creditor by $1m. The two balance. The bank on the other hand records an increase in $1m in its assets (amounts owed to it by customers), and a $1m increase in its liabilities (customer checking account balances). For the bank too, the transactions balance.

But the effect on M1 is that there is now an extra $1m in a checking account somewhere, that is balanced by nothing. It just increased. M1 is $1m bigger as a result of this loan. If the bank has to go get some more reserves, to the tune of 8% or whatever the number is, maybe it only got $920,000 bigger. But it still increased a lot.

Stuart, there is no necessary connection between the quantity of new loans and the quantity of new checking accounts. Over the last year, real estate loans from commercial banks increased $375 billion, whereas checkable deposits fell by $12 billion. An example of how that could be is as follows. Bank makes $1 M loan to Person A. Person A uses proceeds to pay Person B for construction project. Person B uses funds received to acquire CD from bank. At end of the day, bank has $1 M more in outstanding loans (which are not part of money supply) and $1 M more in CD’s (which are not part of money supply). In fact, I believe this is the sort of example discussed in your quote from Wikipedia. The bank loan has not affected the money supply.

However, there is a necessary connection between the quantity of new reserves (this is the magnitude directly changed by the Fed) and the quantity of checkable deposits. Over the last year, reserves have fallen by $1 B, which is the reason that checkable deposits have fallen by $12 B. The reason that there is a necessary connection between these two numbers is that banks are required to hold a certain quantity of reserves for each $1 of checking accounts on their books.

If Person B had insisted on holding $1 M in funds in the form of a checking account rather than a CD, then somebody somewhere else in the banking system would have had to give up $1 M in checking account balances given the overall reserve requirement. One way this could happen is that the original bank, seeing its checking deposits had gone up by $1 million, would sell off $100,000 in some other asset in order to get the reserves it’s required to hold from another bank. But the person who wrote that $100,000 check has then left their bank short on reserves, so it has to adjust. The end of this process would have to be that total checking accounts at other banks went down by $1 M if there is indeed $1 M more in checking accounts at the bank that started this.

The process is a little more involved than this because different sized banks face different reserve requirements, and there are some excess reeserves in the system. But that is the essence of how it works.

In the old days (’70s and ’80s) one of the ways that people adjusted to inflation was to demand higher wages. In those days, unions were more effective and obtained wage increases which caused firms to increase their prices. Even though overall wages are currently rising, most of the increase is going to the top wage earners who more likely to save it that to spend it. Is it now therefore true that the lack of union bargaining power (witness Delphi’s proposal to cut wages by 2/3) would also make stagflation less likely?

JDH:

I’m not saying there’s a necessary connection between money supply and loans. I’m saying there’s a possible connection, in the sense that there are things people can do that effect the broader money supply definitions that are not directly controlled by the Fed.

I agree that checking accounts directly are controlled by the reserve requirements which the fed can control as it will if it wants to, modulo excess reserves as you note. But the limitations of this are illustrated, for example, by the graph at

http://www.financialsense.com/resources/fed/moneysupply.htm

which shows M1, M2, and M3. The changes in M2 and M3 are not particularly well correlated with M1, and are in particular have generally been growing faster (which is the Wikipedia’s point I think).

Also, the table at

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Money_supply

makes it clear that M1 is less than 1/6 of the M3 money supply.

But when we say “money supply”, as in the stuff that people might spend on goods and services, and which we have to worry about inflating, it seems to me we have to worry about the broad measures. Even M3 strikes me as a little narrow as it doesn’t include credit lines, but all of these are things that people can throw at trying to buy goods and services if the latter come into shorter supply.

Consider an economy in which there are $1b in checking account balances, and $3b in unused credit limits on personal credit cards and company credit lines. Let’s suppose normally, before some kind of resource shock, people and firms spend $5b per year on goods and services. A severe resource availability shock causes the amount of goods and services to be reduced in a certain year by 20%. Prices go up, to try and ration the 80% goods and services between the consumers and firms. Now, you would argue we only need a one time 20% inflation. But let’s say the people in this economy are very determined consumers, and in addition to spending their $5b dollars of annual wages, they are also prepared to run their credit cards and corporate credit lines up to the limit over the course of the year (but don’t change their checking balances at all) in an attempt to maintain their lifestyles. Thus an additional $3b is spent. Since the economy is supply constrained, this does not result in the production of any more goods and services, but just in further price increases. So now households and firms spent $8b dollars, to buy what would have been $4b dollars worth of goods and services before the shock (80% of $5b). So I argue that is 100% inflation. Notice that M1 money supply changed not a jot (in nominal terms – it dropped by half in constant dollars).

I realize this is a toy example, but I still think this is an important point.

It really comes down to is the energy shock temporary or not. My guess is it is NOT all that temporary… that it will take a serious across the board ‘output decline’ to drop demand sufficiently over the short & intermediate term to match up with the supply of energy & other energy intensive resources (plastic resins, aluminum, etc).

Even if Katy & Rita hadn’t blown up the Gulf… I think we would be tight with the demand growth in China.

So even with the money supply increasing the output will remain ‘resource constrained’ and lower than optimal… you get stagflation. It will only debottleneck as we ‘innovate’ around some of the physical constraints such as ‘Peak Oil’… I think that will happen but it will take time.

I hope I’m wrong ’cause I was there for the 70s and more than a few of those years we were hungry.

Ray J:

My rough model of what’s been going on is that the top quintile or so have been getting all the extra income, with the lower quintiles being flat in real terms. That extra income has not been used, by and large, to buy goods and services at an unusual rate and so the CPI shows limited signs of inflation (till very recently), despite the extremely low interest rates we have had. However, what has been inflating is various kinds of asset classes – first stocks going to nutso P/Es, and now houses going to nutso price to rent ratios and house prices increasing at 20% annually as people use them as investments and buying them as second homes. These asset class inflations don’t show up in the CPI.

If we were to have an energy shock, or a near-term peaking in oil supply, one of the things wealthy people would be able to do is pull money out of assets and use it to maintain their access to good and services. This would have the tendency of moving this accumulated inflation out of assets and have it start to show up in the CPI (while causing the asset classes to decline).

We do not have a severe energy shock at the moment – only a very mild one. But if we did have a severe one, I predict we would tend to see three things at the same time:

1) Economic stagnation or contraction

2) Inflation

3) Bear markets in stocks and houses.

JDH:

I find odd your assumption that the government is free to control M2 as it wishes. In the graph you show above, M2 and nominal GNP are highly correlated (during the 20th century, it looks like nearly perfect correlation except for the early 50’s)

Apparently, the government is not free to control M2, or else the government does not wish to — the net result seems to be that M2 follows GNP.

Why assume M2 is an independent variable when 100 years of data show that M2 is highly dependent on GNP?

And if M2 is not an independent variable, then how can you be so sure that inflation will remain under control?

It should be noted that the Fed has had a very inflationary policy recently. The rates have been exceptionally low and credit very loose. This should have produced a nice rate of inflation – but it hasn’t. The Japanese have tried even harder – it took a long time before they could beat their deflation even a little.

We could say that the result was an asset inflation. May be, but then we should acknowledge also an asset deflation when housing prices and stocks come down. Curbing assets inflation is possible but not at the same time as trying to cope with a recession. To prevent asset values falling is very difficult. It is the pushing with a rope problem.

It seems that the Fed is not really controlling inflation or deflation. The overall price trends are determined by other factors. First, there are the external factors, foreign trade and international finance. The US is not really controlling the world economy nor even the dollar.

Secondly, there are the investments. Low and lowering investment rates make room for increased consumption and take off inflationary pressure. If the increasing consumer demand is satisfied not by increasing domestic production (which demands more investments) but by imports the accelerator effect is missing. The economy is behaving differently than before.

The stagflation of the ’70s was associated to the petrodollars and increasing profits of the domestic oil producers. In fact the oil crisis brought in a lot more dollars than was paid for the imports of the expensive oil. But these extra dollars were not used in investments and not absorbed in a growing economy. This was of course strongly inflationary.

This time it might not happen. The problem also here is that conventional wisdom and the usual thumb rules don’t work. The US should have fairly strong inflation and the 6.5% current account deficits should cause some problems for the dollar or the rates. But no. There are lot of serious doomsayers about the US economy with very many and good arguments. So far they have had wrong. They all tell us just to wait – the crash will be only worse. But so do all failed forecasters.

Is the US economy really so robust that it will suffer only very mild recessions like in 2001 – 2003 and keep on growing and increasing CAD without problems? My answer is: no. The US economy is not robust nor dynamic – China is. It is mostly China that has kept the global economy going – also the US economy.

This means that the fate of the US economy is essentially not in the hands of the Americans. It doesn’t matter much what the Fed does. The Fed could of course crash the American economy but won’t do that. And nothing else matters much. The US economic development is unsustainable just as the conventional wisdom says but it doesn’t mean it will crash.

The problems start only when the Chinese cannot any more sustain the global economy. The oil shock will affect China less than most countries because the oil imports are relatively so small part of its energy supply. It will suffer indirectly through foreign trade but is the most robust of them all. But China has not much time. It is likely that its domestic energy production will start stagnating in about five years. Then we see.

I feel that this opinion will cause strong reactions here. The analysis could be a little more nuanced. But take this as a hypothesis. Give it a try. May be this helps to explain something.

“why doesn’t the Wikipedia seem to agree with you?”

Wikipedia is full of holwers.

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Pope_Benedict_XVI&direction=prev&oldid=12526972

After all, who writes it?

Erik, the Fed could not hit M2 exactly on the dollar, because the multiplier relating M2 to the magnitudes that the Fed controls directly are variable and not perfectly forecastable. However, the graph displays the 10-year average growth rate of M2, and this is a magnitude the Fed could target pretty accurately if it wanted, by trying to forecast the multiplier each month and making adjustments the following month to compensate for any misses.

Remember also that the graph shows nominal GNP growth, not real GNP growth. When the Fed is making nominal GNP grow faster, primarily what it’s doing is just causing more inflation.

If you look at a plot not of 10-year averages as here, but rather a plot of the 1-year values, you’d see a much looser connection. If your goal is to achieve a particular value for next year’s nominal GNP growth, you’d find targetting M2 growth to be a very blunt and inaccurate instrument.

So, what the graph shows is that the Fed has the ability to control the long-run, broad trends in inflation. The purpose for which I used the graph was as evidence in support of that proposition. I believe you’d find that the vast majority of economists would agree with that proposition.

The intensity of affection I have for this blog continually surprises me. If we need evidence for the academic value of a blog, we need look no further than here.

I would like to throw in another structural change into the equation to see others reaction.

The idea is the impact of the fed announcing the level of targeted fed funds.

Before the Fed make this info public financial market participants had to find it by overshooting and undershooting and this required the fed to make large changes in the level of reserves provided to the banking system before markets settled in on the fed funds rate the fed wanted.

Now, markets move immediately to the desired level. consequently, the fed does not have to make large changes in the level of reserves provided the system.

Interestingly, if you chart free reserves there was a big change in the way they behaved around 1980 — when the fed shifted to announcing the

fed target. In prior cycles we saw massive swings in free reserves. But in the 1990s they were flat except when the fed flooded the system a couple of time to stabilize the system after a shock. In the 1990s the fed left these additional reserves in the system, so the level of reserves looked like a step function.

But, first after Long Term Capial, again after 9/11 and,third, after the 2000 recession the Fed floded the system after the shock, and removed the reserves after they saw the system had stabilized.

One of the reasons I watch free reserves is that it is a great leading indicator of the stock market PE, and this leading indicator has worked extremely well over the past decade.

But, has the supply of reserves experienced a structural shift partially because the fed now

announced the target for funds?

My grandfather had a pig.

He started not to feed him.

Seeing that the pig was eating less he concluded that the pig wasn’t hungry anymore.

“…the Fed has the ability to control the long-run, broad trends in inflation.” I dare to contest this. The is no real evidence. The curve shows only that nominal GDP and M2 are correlated. Controlling inflation is another matter.

Fed policy and the European Central Bank policy and the Japanese CB policy have been very different. But the inflation rate has been rather low in every case. I interpret the recent situation so that there is a very strong global deflationary pressure and therefore the CBs can do whatever they like with same results. Because combatting inflation is a virtue in the CB world they are keen to take credits for this and claim that they now control the inflation. They didn’t control it when inflation was a real problem. For this they accused others, of course. We will soon see if they can control deflation…

It is clear that the CBs have some influence on inflation and deflation but not as decisive they like to think. The Fed doesn’t control the increasing federal debt and the dollar flows in and out of the US, the trade deficit, internationl price levels, productivity etc. We saw above that the Fed can target a 10 year average level of M2 but not 1 year level. This means it cannot control anything really. If the Fed cannot react to inflationary pressures in a 1 year timeframe, it cannot prevent the inflation. It really cannot put the brakes on afterwards. It needs a favourable economic situation to do that. Then they can boast about killing the beast.

The Fed claims that it has created the present “Goldilocks” economy where everything is in the best possible shape. In fact is has not very much to do with it.

I think there is minor typo in the paper by George McCandless and Warren Weber.

There is no “Universidad de Andres” in Argentina. The paper should say “Universidad de San Andres”.

I’ll give here a true story about money and inflation. Have fun.

Time: summer 1992. Place: Belarus border controls. Just entering the country it came to my mind that I didn’t have any cash in the local currency. So I asked a border guard: “What kind of money you have here?”

He answered: “Officially they are some kind of coupons but we call them ‘rabbits’ because one rabbit bill has a picture of a rabbit on it.”

“Can you change some dollars for rabbits? What is the exchange rate?”

“I can give you 1000 rabbits for dollar”.

So I changed a $10 bill and got ten 100 rabbit bills. Those were toy money, small pieces of low quality paper, no serial number. And a picture of an animal (may be it was a bison). Anybody could have made perfectly good rabbits by a copier.

“Excuse me, but there must be a mistake. There should be 10 000 rabbits for ten dollars.”

“No, no. This is correct. You just have to imagine a zero more on the face value. There is a decree on that. This way we don’t have to print new notes.”

A polite form of robbery I thought, but never argue with a border guard with a Kalashnikov and it was only 10 dollars, so what.

In the next small town I went to a shop to buy black bread – there were hardly anything else to buy. The price tag said “270”. I gave three of my 100 rabbit bills. And yes, you guessed right. I got back my two 100 notes and 73 rabbits. Those pieces of paper were real money worth of 10 000 rabbits (there was also the smaller unit, a squirrel. A note with face value of 50 but a picture of a squirrel was half of a rabbit. This was difficult to remember.)

During the next days I changed every day one 1 dollar bill in the local market and got every day more rabbits for it. Soon I had my pockets full of those rabbits. I still have them left. With those rabbits we could eat, buy bread, bottled water and such.

This was a long time ago, the currency of Belarus is no more the rabbit. But how does a central bank prevent rabbits from proliferating?

While discussions of the sources and remedies for inflation are illuminating, I would differentiate financial inflation from the physical problem of stagflation. The former is about managing the money supply and financial system – stagflation has deeper causes.

Start with the premise that industial society runs on exogenous energy inputs. A time of cheap and easy energy will cause a well-managed, entrepreural society to grow and prosper. Cheap energy allows excesses of production that in turn can be invested into further energy and productive enterprises. Good times!

Consider the case were energy costs are increasing (as in increasing EROEI). Now, excess production must be devoted to maintaining energy inputs. The result is that prices increase since the energy required to produce goods and services (including labor) are increasing plus more capital and resources must be shifted to energy production which should offer a higher return on investment. Other sectors have less to invest in productivity increases since energy is starving other sectors.

Result – price inflation and lower growth – stagflation.

Personally, the last period of stagflation was great for my personal finances since experienced energy professionals are then in great demand.

As a side comment, the recent changes in $/Euro exchange rates might be the result of the post-Iraq invasion. US foreign policy has had an unannounced motto: “Forgive Russia, ignore Germany, and punish France.” As evidence I see that the French are converting lots of their wine into ethanol for fuel.

Great story, TI. There are many accounts of substitute money being used in situations such as the U.S. during the Great Depression. And in countries with ferocious inflation, very often another country’s currency (such as the dollar) comes to be more accepted.

In answer to your question, how does the central bank keep that from happening, I believe the general answer is that as long as there is a stable supply of the official currency with stable purchasing power, which serves the basis for all legal debts (such as paying taxes), there is a natural preference for using that currency for all transactions. Your “rabbits” come into use when the government basically fails at that task.

Prof: that article was awesome. Me being an engineer, i am still not able to put together total US household net worth of 50 trillion (total assers 60 trillion-$10 liability, which includes mortgage liability).

Now even accouting for doomsday scenario of 60% reduction in house prices, to me that still looks like a very impressive number (at a macro level)

Now many have stated that fed has been pumping money into the system (by 6-7%??, i believe)for the last 3 yrs (increase M)..but you show 6-7% increase as no big deal if GDP (which has) goes up by 3% or thereabout..So these huge assets appreciation worldwide are merely interest rate phenomena..but how come they are so spectacular?..

you also state….. Stuart, any time that a bank credits you additional funds in a checking account, it is required to hold a certain amount of funds (called reserves) in a separate account with the Federal Reserve. The Fed doesn’t give them these reserves just because the bank made a loan or has collateral. Your bank basically had to get the reserves from another bank, which loss of reserves would reduce its ability to create checking accounts….

i believe you are saying these reserves are just electronic records (and not cash again)..and banks cannot create loan out of thin air…so where is the “reserve” for the apparent credit bubble?

JDH:

It seems you have a lot of faith in the ability of the Fed, and I’m not sure my point was understood.

You say:

” When the Fed is making nominal GNP grow faster, primarily what it’s doing is just causing more inflation.”

Why not say, ‘when nominal GNP is making M2 grow faster”? It seems you start by assuming that the Fed can control inflation and thereby deduce that the Fed can control inflation:

“So, what the graph shows is that the Fed has the ability to control the long-run, broad trends in inflation.”

Or, it shows that inflation is an independent variable and M2 is forced to follow real GNP + inflation.

“I believe you’d find that the vast majority of economists would agree with that proposition.”

I suppose it is comforting to believe that one has control over one’s economy if one has spent a career studying how an economy behaves. But I’d prefer evidence to such comforting faith.

Besides, some economists (who actually put their money and career at risk to their assumptions!) doubt that the Fed is relevant:

http://www.hussman.net/html/fedirrel.htm

Sam, an asset price can go up without any change in the quantity bought or sold. For example, your house likely went up in value this year even if you didn’t sell it. For this reason, there doesn’t have to be any “reserve” for the apparent credit bubble.

One simple formula for house prices says that the price of a house (H) would be related to the rental rate (s), nominal interest rate (i), and rate of growth of house prices (g) according to the formula

H = s/(i-g)

So when the Fed drove the interest rate i so low, that could drive house prices H way up.

Erik, I believe I did understand your point.

I didn’t start by assuming that the Fed can control inflation. I started by knowing that the Fed can control the money supply. If you know that fact, you’re forced to draw the conclusion from the evidence that the Fed can control inflation over the long run.

JDH:

“I started by knowing that the Fed can control the money supply”

How tight a control does the Fed have over M2, and what is your evidence?

“If you know that fact, you’re forced to draw the conclusion from the evidence that the Fed can control inflation over the long run.”

Even if we grant that the Fed could exert strong control over M2, I don’t see how that conclusion is forced upon me. Perhaps the Fed could control M2 at will, but have chosen not to because of other constraints on their actions. Perhaps they been somehow “forced” themselves to move M2 in such a way that it follows nominal GNP? Perhaps inflation is mostly under the control of fiscal policy, and the best the Fed can do is keep from making inflation worse by tryiing to keep M2 following nominal GNP?

Alot has been said about the relationship between inflation and M. What about the demand side? My understanding is that if demand for a currency weakens, then the currency devalues. Is devaluation not tantamount to inflation? Do not the trade and budget deficits contribute to the devaluation of the dollar and thus effectively cause inflation? If the economy goes into recession while the debts grow, could we not get stagflation?

Seems the Fed walks a fine line between raising rates to keep the dollar up, and inflating to keep the real value of debts down.

spencer,

I have been thinking about the short-term relationship between excess reserve and stock market performance as well, in particular, does this explain the old January effect as Fed tends to pump more reserve around end of the year. Have you noticed any regularity around the turn of the year?

Article in todays FT that I believe may be relevant to this, Samuel Brittan: Comeback for money and credit:

http://news.ft.com/cms/s/8e71284e-3c12-11da-94fb-00000e2511c8.html

excert:

“…Moreover, although credit is not the same as money its behaviour cannot be ignored. Lombard Street Research has a series showing world money growth creeping up towards levels last seen around the turn of the century when the world boom in technology shares burst. The development looks more menacing if credit is taken into account. The reason for this is that US banks have been able to step up their lending on the basis of overseas deposits, which do not count in official statistics of the US money supply.” subscription required

I think recession is the greater danger. while the Fed should not do things to create unnescesary recessions, there is nothing they can do to prevent nescesarry ones (bubble correction, 9-11, Katrina, Iraq war, etc.) Those are parts of the exogenous system.

JDH:

“Bank makes $1 M loan to Person A. Person A uses proceeds to pay Person B for construction project… the bank loan has not affected the money supply.”

Sorry, I noticed the discussion between yourself and Stuart a little bit late.

The point I think has been overlooked here is that additional money supplied by the central bank could be USED to produce something that will generate additional economic activity (in this case the construction project) and hence further increases in the money supply, THE PART OF WHICH IS OUT OF THE CONTROL OF THE FED.

Take Japan as a counter-example. There the central bank is trying to engineer a boost to economic activity by increasing the money supply at a frantic rate but it isn’t having any impact on economic activity. There is a de-linking between monetary policy and economic activity.

This is not the case in the US where, as the second diagram shows, M2 has been growing at a brisk (non-zero) rate forever. Long may it last!

The term stagflation is not to be discussed collectively but individually. My personal contribution is that it should be emperically settled individually when discovered. Nationally it is a macro economic tool, therefore the government should be actively involved. Thanks.