As long as you’re willing to twist (or ignore) enough of the facts, you can continue to be persuaded that the earth is actually flat.

Don Boudreaux offered the following observation a few weeks back:

Yesterday, at a gasoline station that I frequently use, I noticed that the price of a gallon of 87-octane gasoline is down 36 percent to $2.17 — down from $3.39 about six or seven weeks ago. I guess this fact means that oil-company executives are 36 percent less greedy today than they were in mid-September.

I would have thought that this observation might have inspired those of the gas-gouging school of thought to re-evaluate their position. I’m surprised to find some of them claiming that no, this observation just proves they were right all along. Houston’s Clear Thinkers notes this exchange between Fox TV new personalities Bill O’Reilly and Neil Cavuto:

CAVUTO: Okay. Gas prices are down a lot. Why do you think that is?

O’REILLY: Because they’re afraid they’ll go to jail. And those C.E.O.s who manipulated them.

CAVUTO: Why are you sure that they manipulated them?

O’REILLY: I have guys that are inside the five major oil companies– my father used to work for one of those oil companies, by the way– who have told me that in those meetings they look for every way to jack up oil prices after Katrina, every way. When they didn’t have to. And they got scared because in my reporting and some other reporting, they said.

CAVUTO: Wait, you’re taking credit for gas prices being down?

O’REILLY: My reporting and reporting of others.

CAVUTO: Has nothing to do with refineries that came back online or the crisis calmed after the hurricanes?

O’REILLY: The demand for oil in this country is the same now as it was one day after Hurricane Katrina. It’s the same. Selling the same amount of gas and oil.

Isn’t it great that we have someone with access to the real inside information to give us the facts? I mean, O’Reilly’s father even used to work for an oil company! I wonder if the “guys from the five major oil companies” also mentioned to Bill that:

(1) The annual oil production of BP, Exxon-Mobil, Shell, Chevron, and ConocoPhillips combined in 2004 amounted to only 12% of global oil production.

(2) U.S. gasoline consumption the week of September 16 was 6.2% lower than it had been the week of August 26 and 4.8% lower than the week of December 9.

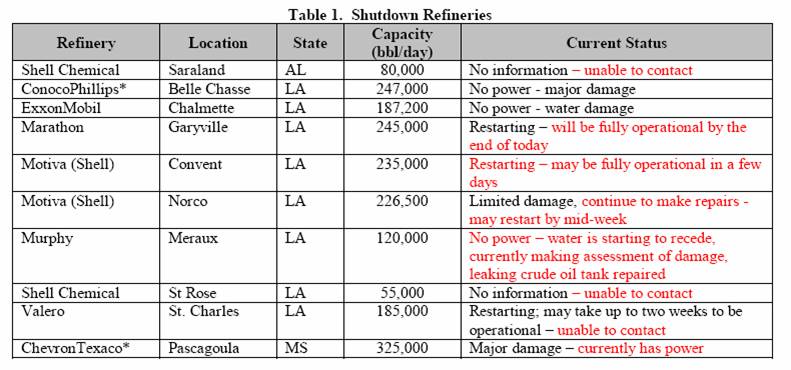

(3) The following table summarizes the physical consequences of Hurricane Katrina for refineries as of Sept. 5:

Of these, all but the ConocoPhillips Belle Chasse and Murphy Meraux are now back in operation.

What, none of the “guys” mentioned these facts to Bill? Well, I understand. O’Reilly’s pretty busy. He has to report the real story to millions of viewers, you know.

Technorati Tags: gas prices,

gasoline prices, oil prices

And does he really believe even the short-run price elasticity of demand for gasoline is zero??

[my fear and suspicion is that he does…]

Having slamed your post on gold to see you do underand the cause of oil prices. You have to wonder what the advocates of the gouging theory are thinking. I mean have they never heard of marginal value and cost of production. Those two factors explain basicly all of price.

I meant to write “..on gold it is good to see you do..”

Nothing like a little sarcasm backed by facts….

I wonder if O’Reilly ever saw this article. (HT: Randall O’Toole at American Dream). It’s got to be embarrassing when even the New York Times realizes that there’s a connection between higher prices for a product leading to lower quantities demanded….

I can’t put all the blame on O’Reilly. We know that the news is a reflection of what the people want to hear. Unfortunately, the majority of Americans have little understanding of fundamental principles of supply and demand. The average person has no idea what the law of substitution is and does not care to learn.

The average American cannot comprehend all the efforts required to operate a simple business. Most who have tried, probably selling Amway or other consumer products, have bitter memories of what it is like. It is easy to lay blame on big successful companies if you have tried and failed at a small business.

O’Reilly should be ashamed of pretending to be so dumb. I am sure it helped his ratings to attack the oil companies. He is a successful showman. Perhaps he is justified for generating vigorous discussion.

My viewing of his show was already on the decline before the series on oil. Now I seldom watch. It is time for internet TV on demand. A show by JH available on demand would be a educational and entertaining on a level that the networks cannot afford.

Is it so ludicrous to believe that a proportion of the gas price hikes could be due to price gouging?

Of course the economics will drive the vast majority of any price change in either direction. But after hearing about the upscale hotels in Paris that were found guilty of collusion very recently, how can anyone say that oil companies are completely incapable of acting similarly, broadly speaking?

I don’t believe oil executives are completely at the mercy of the market.

Examine the reality of managing a refinery. You go to the plant in the morning and reveiw your inventory position. If your tanks are nearing full you need to unload the product and so you drop the price. If the tanks are nearing empty you raise the price. If your tanks get full, you have to shutdown, and you can’t just turn it back on in the morning. If your tanks are empty, it doesn’t make any different that your price is low. You can list at any price when you don’t have anything to sell.

I have to say it again and again. The customer sets the price. When he quits buying the price goes down. When he buys all he can get his hands on the price goes up. The seller can’t force you to buy.

Bill

I’m with you Tim, and think that the interesting question revolves around “proportions.”

It’s about what markets will bear – there is a bit of mass psychology involved, as well as market fundimentals.

If only the economics of the oil industry operated according to the rules of an elementary econ textbook….

Do you really believe it is as simple as you stated it?

Naturally O’Reilly isn’t 100% correct (he never is) because his argument is emotionally charged and not fact-based, but I think it’s equally ignorant to argue from the complete opposite side of the spectrum, which is what many people continue to do.

The truth is almost certainly a shade of gray, although I admit it is probably a whole lot closer to the market forces explanation than the conspiracy explanation.

It is very straightforward why prices would go up and down with shortages. What isn’t clear is why profits would necessarily follow. Below is the comment I put in a previous post but there were no replies.

Oil companies don’t just produce oil, they buy oil — lots of it.

For example, looking at Exxon’s quarterly report, total revenues were about $100 billion but they spent $52 billion buying oil. Their cost of purchasing oil went up 40% compared to a year ago yet their net income went up 75%. As costs go up I would expect profits to fall. How many industries are capable not only of instantly passing on 100% of increased costs to consumers but at the same time increasing profits by 75%? This just doesn’t seem to be a very competitive industry — more like a cartel.

“And does he really believe even the short-run price elasticity of demand for gasoline is zero??

[my fear and suspicion is that he does…”. Its not a question of belief but of basic economic illiteracy for a reporter. He probably has no clue about the meaning of “demand elasticity”. Anyway a “conspiracy” sells many more papers…

I just saw an alarming story on the cable news about “rent gouging” in New Orleans. In particular it seems that greedy landlords are taking empty apartments back from tenants who have left the city, precluding the return of these working class folk, just so they can gouge higher rents from people who actually want to be there now.

One-third the housing stock is gone, and many outside contractors and their workers (paid by the federal government!) are moving in to what’s left, to live in as they rebuild the city. This supply/demand relation is creating a sorry situation.

The local politicians are considering a helpful remedy though — rent controls, and controls that will preserve empty apartments for their previous renters until they decide to return. Take the greed out of the housing market. Who needs people moving in to rebuild the city anyhow?

Anyhow, I saw it on cable TV news so I know it’s true.

Joseph,

Marginal cost of production = cost of raw materials + variable operating costs.

In an oversupplied industry (too much factory capacity) the market price is theoretically set by the least efficient marginal producer covering his cash costs.

In an oversupplied industry, the only way to cover fixed costs and make any profit is the degree to which you are more efficient than the marginal producer. Typically these industries (Think airlines, the historical steel industry, agriculture without govt supports, and the historical petroleum refining)are unprofitable..

In an oversupplied industry, your expection that increases in cost of raw materials are at best passed on to customers is correct.

Gradually supply and demand come into balance, either because the high cost supplier goes out of business or demand grows. In the undersupplied market, prices have to rise to a level where they cover marginal cost of production + fixed + capital costs. Undersupplied industries are profitable and attract new capital, new factories get built, and we go back to being oversupplied.

This completes the cycle.

Before Katrina and Rita, the refinery industry was gradually reaching the “undersupplied market” point where margins were supporting new investment, and were nearing the top of the cycle. Then over a short period, hurricanes knocked out a significant number of refineries leading to a shortage..

O’Reilly succeeds as an entertainer because of an overwhelming societal desire to have confusing topics simplified with broad brushstrokes. Most individuals reserve their deep analysis energy for a core minimum of issues which they individually hold dear. For some it may be oil markets…For others celebrity gossip. We have fleeting interests in issues outside of our core competencies and look for an expert to sum it up for us. Whether it’s economics, the environment, or politics, the best persuaders are those who can summarize, simplify, and exude confidence while doing so.

Doug,

I basically agree with your explanation of refining capacity. But I think the refining industry expansion started a few years ago.

The oft-quoted refining statistic – that half the U.S. refineries have closed since 1980 – is misleading. It’s true that refining capacity dropped throughout the 80’s in response to declining margins. But capacity has gradually increased since the mid-90’s. Refiners didn’t build more plants, they simply expanded existing ones. In addition, companies found ways to decrease sharply the maintenance downtime of their refineries. The nation’s barrels per day refining capacity is nine percent lower than its 1981 peak. But it’s pre-Katrina barrels per year capacity was just about the same.

I was surprised to discover that some refineries were expanded during periods of low refining margins. I guess the decision to expand was based on long-term demand projections. Expanding in advance of demand doesn’t sound very cartel-ish to me.

Here’s a link to a refining capacity graph:

http://tinyurl.com/5qwky

I have been entertained over the past few months with posts, such as Jim’s, which dismiss the notion that their could have any price gouging by the oil companies, refineries, or distributors.

The “supposed” analysis has been a joke.

There could have been some price gouging, but it’s hard to prove (or disprove). I went through this drill at Calculated Risk early on.

Jim clings to the point that “annual oil production of BP, Exxon-Mobil, Shell, Chevron, and ConocoPhillips combined in 2004 amounted to only 12% of global oil production” as one of his prime defenses against the possibility of price gouging on retail gasoline prices. He simply ignores the market share of refined product that these same companies provide to the U.S. market.

A poster, Joseph, stated under a previous thread:

Link: https://econbrowser.com/archives/2005/11/oil_grilling.html

“You have asked the wrong question. Lautenberg said nothing about the price of oil. He mentioned the price of gasoline. These few oil companies control over 90% of the gasoline in the US and are quite capable of manipulating its price. After all, we have seen the cost of feedstock oil go up at the same time that gasoline profits go to record highs. That seems contradictory. In most industries when the cost of production (meaning gasoline) goes up, profits go down. Their profits come primarily not from oil production, but from buying oil and producing gasoline.”

Jim’s response: “Joseph, I believe that the doubling in the price of gasoline should have something to do with the doubling in the price of oil.”

Joseph’s responses to Jim: “But does doubling the price of oil imply the doubling in profits in gasoline? I would think just the opposite.”

“For example, looking at Exxon’s quarterly report total revenues were about $100 billion but they spent $52 billion buying oil. Their cost of purchasing oil went up 40% compared to a year ago yet their net income went up 75%. How many industries are capable not only of instantly passing on 100% of increased costs but at the same time increasing profits by 75%? This just doesn’t seem to be a very competitive industry — more like a cartel.”

Jim’s response to Joseph’s follow up posts: NONE.

Now, on this new post, Jim adds that “U.S. gasoline consumption the week of September 16 was 6.2% lower than it had been the week of August 26 and 4.8% lower than the week of December 9.”

And?

How does this disprove the notion that any price gouging occurred or didn’t occur?

It doesn’t.

If you’re serious about proving or disproving any potential for price gouging on gasoline target pricing, you might want to start with reading some of the links noted in my next post.

Or just cling to the childlike naive notion that there is no way in the world that there was ever a penny of gasoline price gouging.

Analyzing Fuel Data to Determine Any Patterns or Potential Discrepancies in Gasoline Pricing

The lack of posted research on various blogs regarding the posts made by economists and others to challenge all claims, however large or small, that price gouging has occurred in recent months should be cause for concern. There has been very little real analysis. The ability to reach down into available data and draw meaningful conclusions based on real details appears to have escaped most main posters in the “price gouging couldn’t have happened” crowd.

The following data sources are worth noting. While I do not say that recent months’ gasoline pricing was subjected to price gouging because I can’t prove or disprove it 100%, I do note that some of the following data disputes some of the anti-price gouging arguments. Of course, it would help if one could step beyond standard econ theory chatter and study the data to develop an appreciation for the pieces of the puzzle. Some of the answers or potential challenges to the claims are in the following data. It also helps if one understands what he/she is looking for. The lower links provide sufficient information to question some of the naive assertions posted on various blogs.

Weekly Petroleum Status Report

http://www.eia.doe.gov/oil_gas/petroleum/data_publications/weekly_petroleum_status_report/wpsr.html

Petroleum Data, Reports, Analysis, Surveys

http://www.eia.doe.gov/oil_gas/petroleum/info_glance/petroleum.html

Forecasts and Analysis

http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/forecasting.html

Gasoline and Diesel Update

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/oog/info/gdu/gasdiesel.asp

Gasoline Components History

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/oog/info/gdu/gaspump.html

Hurricane Impacts on the U.S. Oil and Natural Gas Markets

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/oog/special/eia1_katrina.html

Joseph and Movie Guy,

The position that “there is no way in the world that there was ever a penny of gasoline price gouging” is an odd one to attribute to me. Certainly I never said such a thing. One of the reasons I never made such a statement is that I am unclear as to the definition of price gouging.

I am on record as stating that imperfect competition makes a modest contribution to retail gasoline prices in some communities in the U.S., largely as a result of regulatory restrictions on competition. I am also on record as applauding the Administration’s decision to reduce these restrictions in a temporary response to the problems raised by Katrina.

In the present post, I respond to the claim by Bill O’Reilly that

I believe O’Reilly’s statement to be refuted by the facts that I cite.

I am not sure what I am supposed to make of the multiple references to data sources. These are indeed the very same data sources that I myself report from all the time, including in the present post. Movie Guy, you’ll have to clarify the sense in which you think any of these linked statistics “disputes some of the anti-price gouging arguments”. For such clarification, please first identify exactly the argument you are responding to, and then explain how the statistic in question seems inconsistent with that argument.

And finally, as to Joseph’s question about why an increase in crude oil prices should raise Exxon-Mobil profits, remember that this is an integrated major, with both production and refining operations. For any oil producer, when prices go up 10%, profits should go up much more than 10%. See for example how the calculations work out here. Furthermore, even a pure refiner such as Valero should see an increase in profits from an increase in the price of crude. The reason is that the scarcity of oil in particular is a scarcity of light, sweet crude, and there is therefore an increase in the profitability for anybody who can turn gunkier stuff into motor fuel, also reflected in a rising price spread between light, sweet crude and heavy, sour.

Movie Guy, posting all of those links is kind of like throwing sand in your opponent’s eyes when you’re losing an argument. If you have analyzed the data and come to some kind of conclusion, the burden is on you to present your findings, not on us to click on your links and do the analysis for you.

I wasn’t going to go there, this time, but if you say you don’t know what gouging is, I think I have a straight answer:

Gouging is a break with human standards of fairness. Those standards borrow some from the great thinkers of economics, and also from the proto-economic impulses we carry around in our monkey-brains.

Actually I should say “gouging is a [large] break” … smaller breaks get different classifications.

Odograph –

Be careful. Fair is a four letter F word.

I have yet to find a transaction that is fair to both sides of the table. When oil was cheap and the industry was struggling with inadequate return on investment why didn’t we in the interest of fairness all send them a little extra money?

Denying a man in the desert water might be a break with most ethics, but offering merchandise at a price that people are willing and able to pay is not unethical.

If cost was a criteria for setting prices then anyone who earns more than minimum wage is unethical, because it costs just as much to feed the minimum wage earner as it does the guy who makes twice, three times, or twenty times minimum wage.

Crying price gouging is simply an appeal by a despot.

Bill

Jim — “The position that “there is no way in the world that there was ever a penny of gasoline price gouging” is an odd one to attribute to me. Certainly I never said such a thing. One of the reasons I never made such a statement is that I am unclear as to the definition of price gouging.”

Come on, Jim. Please. You need a definition?? You need perfection before you can address the possibility of price gouging?

I’ve read your posts on crude oil. And on gasoline prices. Your June post was a good one, as were some others.

I am referring to your remarks here and elsewhere since August 2005.

There is no question that the quote you attribute to O’Reilly was an incorrect statement on his part. I listened to him say that when he made the remark. I shook my head.

But what you did in this post was gloss over the possibility that any price gouging could have occurred. What you did do, though, was belittle O’Reilly in a very snotty manner, almost as bad as his behaviors on television:

Jim — “Isn’t it great that we have someone with access to the real inside information to give us the facts? I mean, O’Reilly’s father even used to work for an oil company!”

You still have not addressed the question of whether price gouging could have occurred. Guess you’re waiting for someone, perhaps Congress among others, to define what “price gouging” could possibly mean.

Now, you made the following statements as well:

Jim — “I am not sure what I am supposed to make of the multiple references to data sources. These are indeed the very same data sources that I myself report from all the time, including in the present post.”

I do not recall seeing you cite or refer to any of the following specific links:

U.S. Finished Motor Gasoline Refinery Yield (%)

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/dnav/pet/hist/mgfryus3m.htm

U.S. Refinery Utilization and Capacity

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/dnav/pet/pet_pnp_unc_dcu_nus_m.htm

U.S. Weekly Percent Utilization of Refinery Operable Capacity (%)

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/dnav/pet/hist/wpuleus3w.htm

U.S. Refinery Yield

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/dnav/pet/pet_pnp_pct_dc_nus_pct_m.htm

U.S. Regular All Formulations Retail Gasoline Prices (Cents per Gallon)

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/dnav/pet/hist/mg_rt_usw.htm

Weekly Imports & Exports

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/dnav/pet/pet_move_wkly_dc_NUS-Z00_mbblpd_w.htm

U.S. Weekly Crude Oil Imports (Thousand Barrels per Day)

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/dnav/pet/hist/wcrimus2w.htm

U.S. Weekly Total Gasoline Imports (Thousand Barrels per Day)

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/dnav/pet/hist/wgtimus2w.htm

My point is that looking this deeply into the subject of gasoline production, refined product import, and comparison of finished product costing doesn’t happen very often.

The links above, in conjunction with the following links, could provide for the basis of a good discussion:

Gasoline Components History

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/oog/info/gdu/gaspump.html

Hurricane Impacts on the U.S. Oil and Natural Gas Markets

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/oog/special/eia1_katrina.html

If you or anyone else studies the data under these links for the period of June (a good starting point) to latest data presented, it’s obvious that there is some interesting information available which offsets the implied and anticipated concerns presented in the September 2005 Table 1. Shutdown Refineries chart that you posted above. The lost capacity wasn’t the main issue, though I thought it was originally. The issue focused instead on overall national production and imports of refined gasoline product. It was a mistake to simply focus on the shutdown lost capacity as opposed to noting the ramp up of production elsewhere. And the data is available to make that point.

Originally, I attributed all price increases to the disabled or partially operating U.S. refineries in the Southeast. Then I talked to some oil distributors and dealers I know personally. And parts of the story changed at that point. That’s when I tracked back to the EIA data as it rolled in.

I will leave you with a few simple questions:

1. Did the refining capacity shortfall cause all or most of the gasoline pump price increases?

2. How large was the overall national refining production shortfall? (Note that I didn’t say ‘capacity’) What percentage?

3. What were the costs to distributors of the refined gasoline product imported during the period concerned? And where did most of the refined gasoline import product originate?

4. How were gasoline deliveries inventoried and costed at the dealership level during the period concerned (as well as before and since)?

5. If you have a valid definition for “price gouging”, how would prove or disprove the presence of price gouging without having full CPA access to the books of the oil companies, distributors, and dealerships?

Can price gouging occur? Sure. But it’s damned hard to prove, as is collusion among the bigs or the distributors. Very hard, indeed.

Jim, you can belittle people who have made statements about price gouging all day long. But you haven’t disproven their statements or similar concerns from others. You’re still waiting for a definition by your own admission.

So, why whack idiots like O’Reilly when you don’t offer clear evidence that price gouging didn’t occur?

Your post looks more political than factual. Sort of like your automotive posts, which tend to hammer away at SUVs instead of representing detailed study and analysis on all vehicle sales and production costs.

Price gouging? How would we know the truth? The analysis is lousy.

John S. — “Movie Guy, posting all of those links is kind of like throwing sand in your opponent’s eyes when you’re losing an argument. If you have analyzed the data and come to some kind of conclusion, the burden is on you to present your findings, not on us to click on your links and do the analysis for you.”

I never presented a pro- or anti-price gouging argument.

What I did do is provide some specific data sources that would help others come to their own conclusions which would at least be partially based on real data.

Part of my findings is the available data. I showed you where that data is located. Read it yourself and draw your own conclusions after comparing one set of data with other sets. If you understand how to relate one set of data with another set, that is.

Movie Guy and odograph,

The reason I feel oil retailers and oil refiners have treated their customers fairly is not because I’m childlike or naive. It’s simply that I believe they’ve used the only fair and efficient means of rationing a scarce good, which is pricing. Allowing producers to charge what the market will bear is the way that we ensure price-based rationing.

Allowing suppliers to raise prices and increase profits encourages two other actions that benefit customers:

1. It causes an immediate shift of goods to an undersupplied market. Evidence: the increase in gasoline imports from Europe that did occur in September and October. Would European refiners have incurred the cost to ship this gasoline across the ocean if prices had not risen? I don’t think so.

2. Increased profits send a signal to suppliers that they will be rewarded for increasing inventories in advance of an anticipated outage and for increasing production after. Both actions benefitted consumers in September and October.

Please consider also that the U.S. gasoline market may not be as concentrated as some believe. The largest refiner, Valero, has only an 11% share. The top 5 refiners own only about 45% of the nation’s capacity, and the top 10 only about 80%. Though local concentrations exist, the network of pipelines extending out from the Gulf Coast allows most of the country to benefit from competition among refiners.

I welcome hearing your courteous disagreement with my arguments.

JohnDewey,

I appreciate your response.

I don’t disagree with your generalizations, but they don’t disprove price gouging. And the title of Jim’s post is ‘The ungouging of gas prices’.

I do suggest that few have studied the details adequately to make the case that no price gouging occurred. I have studied much of the data in detail, met with industry representatives, and retail suppliers, and I can’t prove that price gouging didn’t exist. I can say it, but I can’t prove it. And I’m a pretty good researcher.

Example, has anyone posted a main blog post that captured the cost data for gasoline refined product imports during the period of August-November? And it was compared to what U.S. production cost in such analysis? If the production cost to point of retail delivery was, in fact, different (meaning less), did the pump prices reflect the delivery differences? Sure, we can assume price averaging, but that overlooks the way prices move at the retail level of gasoline. Same story for inventory consolidation (liquid mix).

We have been importing gasoline refined product for quite a while, longer than the period under discussion. Did those refined product costs jump during the post-hurricane period? And, if so, they increased for which entities? The shipping was freed up by the President, so didn’t that help offset some transportation costs due to U.S. flagged tanker shortages or potential premium mark up?

Europe has been sitting on excess gasoline refined product capacity. And our fuel suppliers have enjoyed its feed. So, gasoline refined product imports are nothing new.

In the Southeast, where the impact was felt more strongly than further up the coast (in my judgment), the supply feed was primarily regular grade 87 octane gasoline. Yet, the price mark up for 89 and 92/92 (in comparison to 87) remained pretty much the same. Yet, the larger shortages were in the higher octane grades. That was a bit odd at the time if one is to assume that pricing vs demand drove the target prices.

I believe your second point has merit. It does, though, overlook the production substitution factor that was in play at the time. The concentration of effort was on gasoline refined product.

There are many points which can be made for either side of the pro- or anti-price gouging argument. Similarly, the discussion of available gasoline finished product supplies can be more detailed than it has been to date. Enough information is available to pursue either or both discussions. We haven’t witnessed a broadening of the discussions to include that level of data analysis.

Typically, the discussions have been limited in scope and consideration at most econ blogs. Plenty of people (as sub-posters) just laugh and scoff at those who say or suggest that “price gouging” occurred. It’s an intellectual superiority demonstration in some instances. Which is rather arrogant, considering that few of those people post any supporting evidence and data to counter the “price gouging” arguments.

It is one matter to know the facts, and quite another to be flippant and smug when addressing the possibility of price gouging. On both sides of the argument. I suggest that some of the “informed” intellectuals who profess to know that no price gouging occurred are not supporting their arguments and sarcastic slams with substantial proof. I don’t believe that they have done the research to back up their claims. It’s that simple in my judgment.

Laziness is not a virtue. Nor is being smug and flippant, as some have demonstrated on various blogs. Misplaced ‘supposed’ intellectual superiority is hardly an argument of merit.

If one is saying that price gouging did not occur, then at least try to prove it. Few have. Few will in my judgment.

I have enjoyed the dialogue on this weblog. In the discussion on the oil sands I found at least something I agreed with in nearly every post. I also hope we can keep disagreements courteous.

Movieguy and Odograph,

I think I agree to a point with Odograph about gouging – huge mark-ups above cost when people are in distressed circumstances are wrong.

I tried to gather some data on profitibility per gallon of clean products (gasoline, diesel, heating oil, jet). The cleanest way to do that was to look at the 3Q04 vs 3Q05 profits of Valero. I picked Valero because they are a pure refining company and as someone mentioned by some measures the largest.

I apologize for not being able to format a table in the comment fields – I hope this is readable:

3Q04 3Q05

net Profit, M$ 434 862

Clean prod. MB/D 1906 1685

c/g 6 13

So, Valero’s profit from refining doubled in

3Q05 vs 3Q04 – on a per gallon basis more than doubled.

I have a hard time seeing this as a “huge” markup.

There was a really good article in Forbes about the St Charles, Louisiana Valero refinery after Katrina. There were fuel users in distressed circumstances – hospitals with emergency generators, gasoline for ambulances, etc. If Valero had taken advantage of the situation and sold the existing fuel in their tanks for $10 or $20 / gallon that would feel like gouging. (According to the article they donated the fuel).

To a motorist in, say , Atlanta, profits as a percent of retail price, profits increased in single digits. Does that really seem like gouging to you?

I actually agree more with Bill Ellis above than you might guess. I mean, maybe I “feel” it a little bit as I see prices at the pump go up and down, but that’s minor. I think it is much more interesting that this “fairness” issue is there, as a subtext to every gasoline and gouging discussion.

To be clear on where I diverge though, I can’t agree with:

“Crying price gouging is simply an appeal by a despot.”

See, I’m thinking that maybe:

“Crying price gouging is simply an appeal by a human.”

I’m trying to keep my personal fairment judgement out of it, and I’m must stepping back to observe that everyone is making fairness judgments … even people who call the hoi polloi (all those people calling their congressmen) “despots.” 😉

So, “price gouging” is “charging unfair prices”.

Now define “unfair”.

And please, don’t try to tell me that charging more than marginal cost is “unfair”. Besides, in regions hit my natural disasters, the relevant marginal cost is the cost of replacing the good in question, not the marginal cost of purchasing the good currently for sale. And the marginal replacement cost is very high indeed, for a short amount of time. But guess what: charging a high price means the shortages get alleviated quicker. Anti-price gouging laws only exacerbate shortages, amplifying human suffering.

Legislating against economic reality makes about as much sense as outlawing gravity. Yet politicians can’t seem to help themselves.

I think this issue arises from two differences of opinions: one about property rights and one about whether free markets work.

Many citizens – and a few states attorneys general as well – do not want to give the same property rights to oil refiners and service station owners that are granted to everyone else. I firmly believe that the owner of a good or service has a right to sell it for whatever price he wishes. As long as the state does not invoke eminent domain, homeowners are free to sell their house for whatever price they can obtain – or they can just hold on to it. McDonald’s can set whatever price they wish for Big Macs. Safeway and Krogers can charge whatever they wish for milk. Why shouldn’t gasoline retailers be allowed to charge whatever they wish for the gasoline they own?

Why can’t the general public accept that the gasoline market is a free market? Even though the grocery industry is much more concentrated, and their products are much more essential to life, we accept that the free market is giving us the lowest prices. From time to time we do have sharp increases in coffee prices and in orange juice prices, but I don’t remember hearing charges of collusion among the grocers.

Anyone who drives through a large city can see the evidence that gasoline prices are not being fixed. The Valero station prices are never exactly the same as the Murphy prices or the Exxon prices. In fact they have differed by as much as 10 and 15 cents a gallon recently. Why do some believe that price collusion is occurring? And if we accept that companies are not guilty of collusion, then why don’t we trust the free market?

“Now define ‘unfair'”.

That’s interesting, isn’t it? We might all choose different values, but would US society as a whole have a meaningful consensus?

FWIW, I think the old “ultimatum game” expiremental economics highlights that there can be concensus values of fairness in human societies.

“Why can’t the general public accept that the gasoline market is a free market?”

I agreee that the gasoline market is mostly free …

Maybe the history of things like the Texas Railway Commission, and OPEC, influence people to think that it is not completely free?

Or for that matter, the fact that drilling our last remaining large oil reserve (ANWAR) is not an economic decision, but a congressional one.

There is constant “crosstalk” between the political world and the oil industry. Heck, didn’t Hugo Chavez set the oil heating price for poor folks in the northeast?

In a mess like this people who take the extreme views that “it’s all greed” or “it’s all markets” have to both be partially wrong.

Another case where the moderate view wins 😉

Price-gouging (to a degree) must be within the realm of possibility…….

BBC

April 1, 2003

Oil firms fined for price fixing

Petrol prices are often controversial

The world’s four largest oil firms have been fined for fixing the price of petrol in France.

The French subsidiaries of BP, Shell, ExxonMobil and TotalFinaElf were fined a total of 27m euros ($30m; 19m) by France’s competition authority for price colluding at service stations.

The regulator said the firms “frequently and repeatedly” exchanged data to set petrol prices at the pump by telephoning each other several times a week in 1999 and 2000.

“Such practices helped favour a rapid convergence of prices to a higher level than would have prevailed if oil companies had followed their own pricing policies,” the statement read.

France’s oil giant TotalFinaElf recieved a fine of 12m euros, while the other three were charged 5m euros each.

Denial

But the French firm has denied any wrongdoing and has said it will appeal against the charge.

“TotalFinaElf has done nothing more than collect information on prices displayed by other service station operators, which is a normal part of doing business in a competitive environment,” the firm said.

Multinational oil firms have frequently been criticised, especially in the UK, for saddling motorists with high petrol prices and being slow to pass on falls in the wholesale oil price.

The oil firms, meanwhile, argue that sales of petrol at the pump have very limited profit margins.

The Age

Petrol companies guilty of price fixing

December 17, 2004 – 2:46PM

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) has won a landmark case against petrol companies that fixed fuel prices in the Victorian city of Ballarat.

Federal Court Justice Ron Merkel found four companies – Triton 2001 Pty Ltd, Apco Service Stations Pty Ltd, Brumar Pty Ltd and Cavallo Volante Pty Ltd, formerly Balgee Oil Pty Ltd – entered price fixing arrangements up to 69 times between June 1999 and December 2000.

The four companies and three senior managers, Triton Ballarat area manager Anthony Brian Rosenow, Apco Service Stations director Peter Joseph Anderson and Brumar retail area manager Garry Victor Dalton, were the subject of today’s proceedings.

The parties contested the ACCC’s case but Justice Merkel found managers from the companies used phone conversations to orchestrate price rises, in contravention of the Trade Practices Act.

“The contraventions, which involve serious and on-going breaches of important provisions of the (Trade Practices) Act, resulted in the price of petrol in Ballarat being the subject of a cartel type of arrangement or understanding over a substantial period of time,” Justice Merkel said in his judgment.

“It was an arrangement or understanding that led to the public paying higher retail prices for petrol than they would have paid if the prices had been determined by market forces, rather than by a collusive arrangement between competitors.”

The parties will return to the Federal Court for a penalty hearing on March 7 next year.

Nine other respondents, including Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd, Leahy Retail Pty Ltd, Chisholm Pty Ltd, Justco Pty Ltd and five men, admitted the ACCC’s case against them.

They are subject to separate penalty hearings before Justice Goldberg. Judgment has been reserved.

Combined, the companies involved in price fixing ran BP, Shell, Ampol/Caltex, Swift, Apco and Mobil outlets in the Ballarat area.

Ballarat’s Ampol Road Pantry petrol station was not included in the action.

Can we use crude oil market imperfections – such as OPEC and Texas Railroad Commission intervention – as evidence that gasoline markets are not free? Aren’t those two separate and distinct markets? Only a small percentage of gasoline retail outlets are operated by oil producers. I don’t think any of the gasoline wholesalers – known as jobbers in the industry – are producers or purchasers of oil. Some of the largest refiners, such as Valero and Sunoco, are not oil producers. What evidence do we have to indicate that today’s gasoline markets are not free? The only significant restrictions on U.S. gasoline I know about are the special blend requirements of certain states. But that’s not the collusion being argued by recent critics of gasoline refiners and retailers.

We can probably find tiny shreds of evidence that gasoline markets are not totally free. Those of us who argue that free markets exist are really meaning that gasoline markets are just as free as every other goods market in the U.S.

IIRC, around the time of Katrina people were talking about the relative prices of oil and gasoline. There was even some talk of strange linkages, with high gasolie prices driving oil futures higher.

I’m sure it must be work for an academic, to extract the “oil” component of “gasoline” price:

http://inflationdata.com/inflation/Inflation_Rate/gas_vs_oil_price_comparison.htm

Anybody know how it works for refiners … what fraction of their input they buy for long-term future delivery, and what fraction they buy at short term prices?

odograph,

Can you explain what point you’re arguing with the graph? Is it that the price of this manufactured good is highly correlated with the cost of an input? I think that would be true for many goods, right? For example, when orange growers suffer crop losses due to cold weather in Florida, the price of orange juice will soon rise. But that doesn’t mean that either the orange juice manufacturers or the grocery store chains are “price gouging”, does it? Actually, I have no idea what the term “price gouging” means, so maybe Safeway is guilty of the offense. Maybe they’re supposed to sell OJ at a loss.

JohnDewey — “Actually, I have no idea what the term “price gouging” means…”

Care to identify the State that you live in?

MovieGuy,

I live in Texas. The attorney general has advised us that:

“It is a false, misleading, or deceptive act or practice to take advantage of a disaster declared by the governor under Chapter 418, Government Code, by selling or leasing food, fuel, medicine, or another necessity at an exorbitant or excessive price.”

I have found no official definition of exorbitant or excessive. A spolkesman from the Attorney General’s office explained recently that price gouging is the “exorbitant or extensive increasing of prices beyond the prevailing prices in the community.” I don’t think that language is actually in the law. But even if “prevailing prices” does hold up in court, what does it mean when all gasoline retailers quickly raise their prices 50 to 60 cents a gallon?

As I explained in my letters to legislators and the state attorney general, I am opposed to any government interference with gasoline market prices. Unfortunately, too many of our citizens are ignorant of basic economics and will support the attorney general in battling market forces. Their continued ignorance will eventually do great harm to the welfare of us all.

Carnival of the Capitalists 12/19/2005

Welcome to the Carnival of the Capitalists and my second time hosting the COTC. Note that several people tried to submit multiple posts – when that happened, I picked just one to include this week. Many thanks to Silflay Hraka

This Week’s Carnival of The Capitalists

This week’s COTC is up at Coyote Blog. In addition to hosting the Carnival, he’s also taking the opportunity to showcase some of the Acme Company’s products from RoadRunner/Coyote fame – very nice. As usual, here are my picks:

JohnDewey, I was just struck by your earlier lines:

“Can we use crude oil market imperfections – such as OPEC and Texas Railroad Commission intervention – as evidence that gasoline markets are not free? Aren’t those two separate and distinct markets?”

How “free” are we going to categorize gasoline markets, given “that the price of this manufactured good is highly correlated with the cost of an input?”

I think you’ve got it, JohnDewey. “Gouging” appears to mean, “Any price I don’t like” or, more specifically, “Any price that forces me to reconsider the choices I have made regarding how I live, i.e. the size, construction, and location of my house relative to my local climate and the distance to work, shopping, and amusements, the means by which I travel between them, the size of my family, etc.”

There was a joke making the rounds recently about three men in a cell, one of whom is accused of predatory pricing because his prices were lower than those of his competitors, the second of collusion because his prices were identical to those of his competitors, and the third of gouging because his prices were higher than his competitors. Indeed, we do not live in a free market society when people have to make decisions about pricing not on an economic basis, but on the basis of how to stay below the radar of grandstanding politicians. We could try to artificially contain the prices, but this would force a different choice: that of dealing with a lower supply of fuel, and the corresponding consequences, i.e. lower growth rates, less mobility, etc. Bastiat proves himself again: the higher prices are easily seen on almost any street corner, but the alternative is a set of consequences which are not as easily seen.

Odograph wrote: “How free are we going to categorize gasoline markets, given that the price of this manufactured good is highly correlated with the cost of an input?”

——————————————-

Gasoline manufacturers have been able to pass through the cost of their major input. Does that say anything about whether gasoline wholesale and retail markets are free of interference from government and free from collusion by sellers?

I’d appreciate a little insight about this very basic issue from the economists. It’s been 20 years since my last MBA economics class, and I can’t be positive I remember everything.

I can think of a very simple reason why gasoline prices will be highly correlated with rising oil prices. The commodities markets function very efficiently, and information about oil prices is immediately available to gasoline refiners and wholesalers. Since refiners and wholesalers know they must cover the replacement cost of their inventory, they should try to increase prices as soon as they are aware of an oil price increase.

I’m not positive, but I believe that the mechanisnm to reduce gasoline prices at the pump operates slightly slower. Information about whether retail competitors are going to lower prices, and about whether a previous increase is going to stick, is not instantly available to the retail operator. So he hangs on as long as possible to the higher price. In just a couple of days, though, competition forces prices back down.

I’ve read an analysis about the stickiness of gasoline prices following input cost decreases, but I can’t put my hands on it right now.

Eric H – “Any price I don’t like”

I think human nature is a little bit of a mixed bag. I wouldn’t endorse every primal impulse. That said, when we observe a broad human response (like a very wide antipathy toward “gouging”), I think we should dig into it a little bit before delcaring it good or bad.

Certainly, if it originates from an impulse to “pull together in time of emergency, and punish ‘cheaters'” … that might have some value.

Step back and think about how we differentiate prices and gouging. No one is writing to their congressmen because Christmas chocolates are at a 500% mark-up. No one is excited because Ferraris cost 10x Toyotas. Something is different about gasoline. I’d suggest the difference is that we judge it as either necessary to our day-to-day survival or critical in emergency.

I hope you caught that when I said “our monkey-brains” (way up at the top) I was being semi-derisive. Those are the brains we’ve got. They may allow us to make semi-rational blog comments, but we can’t expect everyone to be (or even choose to be) “rational economic agents”

“Something is different about gasoline. I’d suggest the difference is that we judge it as either necessary to our day-to-day survival or critical in emergency.”

And that’s all the more reason why we should leave gasoline markets alone. Free markets work. Governments have tried allocations, price controls, alternate energy incentives, theats to punish so-called “price gouging”, and all other sorts of intervention. None work as well as free markets to serve the needs of consumers. Government is just not going to beat “Invisible Hand”.

Without government, Standard Oil would still be a monopoly and we would all be in serious trouble…….

Free markets don’t always work. History has proved this time and time again.

How can some economists be so naive about the complexities of the real world?

The situations described above where competitors join together to set prices, or signal to their competitors price changes are examples of anti-trust violations (under US law), not price gouging.

When you think about pricing in emergency situations, consider the exodus from New Orleans or Houston. If we have two gas stations at an exit, with one pricing gas at $2 per gallon, and the other at $4 per gallon, we can expect a number of things to happen. First, the low price station is going to sell a lot of gas, folks will be encouraged to fill it to the brim, noting the compitors prices. But, unless he has a bottomless supply he will soon be out of gas, and no one can benefit from his low prices. The fellow with the $4 gas will have to wait for that event to happen, but he will have the precious commodity of an inventory when no one else has any gas.

Both of these owners are making assumptions in their pricing. The low cost guy thinks he will get another tanker soon, while the high priced guy thinks it may take a week. The profitability of the two approaches will vary not on price, but on the reality of the duration of the shortage. Both serve a place in merchandising, but neither is evil. There is market for Tiffany’s and there is a market for KMart.

Bill

Bill,

Compare your hypothetical case with what actually happened in Houston:

1. Rather then assuring citizens that gasoline would be available, the media and some Texas leaders warned citizens to expect shortages.

2. Prior to evacuation, the Texas Attorney General threatened to prosecute gasoline retailers who “gouged”.

3. Retailers then kept gasoline prices artificially low instead of raising them to market-clearing levels.

4. Early evacuees, fearing shortages and facing no incentive to hold back purchases, bought nearly all the available gasoline the first day.

5. Many Houston families, including those of my two brothers, could not find gasoline to evacuate.

Threats to prosecute price-gougers eliminated the price rationing that would have allowed everyone teh gasoline needed to evacuate. Those threats also removed incentives for gasoline wholesalers to shift additional supplies to the Houston area in an emergency.

Pre-Rita Houston was not a theoretical exercise in the failure of government interference. Government-induced shortages really happened.

So you’re saying that if retailers had raised prices to “market clearing” levels, evacuees who had just recently watched Katrina destroy New Orleans would not have purchased nearly all the available gasoline the first day?

I believe that, in view of the panic and anxiety surrounding those days, raising prices to “market clearing” levels simply would have allowed oil companies to reap even more spectacular profits than they did.

Further, the first-come-first-serve marketplace would have been unchanged, and I think most people who watched Katrina unfold on TV would agree.

JohnDewey – “all the more reason why we should leave gasoline markets alone.”

I think the average American could use a little education on the market-nature of existing gasoline distribution, but … what then, they write their congressman to support/oppose CAFE? They write their state to support/oppose highway bond measures? What about the Hydrogen Highway? Hybrid tax credits? Ethanol subsidies? Federal funding for oil shale?

… I’m sorry but I get the idea that it’s easier to focus in on one tree in this whole forest of complexity … and pretend we have a free market in gasoline.

Tim,

If Houston gasoline had been priced at $5.00 a gallon instead of $2.70, some evacuating families would have driven to Dallas in one car instead of in two or three. Some who had 3/4 of a tank would not have topped off in Houston, but would have waited for lower prices down the road. Some who filled up spare five gallon containers would not have done so.

The biggest impact, though, would have been on the supply side. Wholesalers from around Texas would have diverted supply to Houston in advance of the evacuation. Their share of the higher-priced gasoline would have covered the extra transport costs plus provided them extra profits.

John,

You believe that if oil companies were allowed to price-gouge the Houston population with Rita on the way, that would have better for them on the whole?

That model seems sound, until you examine the implicit assumptions made. I don’t believe people would have rationally decided not to fill their tanks to the brim and get out as quickly as possible in order to potentially save some money.

I also don’t believe people would not have stocked up as much gas as possible because they were worried about their personal finances. At the time, Rita was a 165 mph hurricane that looked scarier than Katrina.

I also don’t believe that wholesalers would have supplied Houston with substantially more gas only if they the profit margins were higher. The market had shortages well after Rita – was it because Houston just wasn’t profitable enough for oil wholesalers to supply?

I don’t believe price gouging would have made matters better for the Houston population on the whole, but rather for oil companies and those consumers that had relatively more money to spare.

I just can’t believe that homo economicus is who we’re dealing with under these sorts of extreme circumstances, whether we’re talking about oil execs or consumers.

Tim;

Standard Oil’s market share had fallen far below 90% by the time the government got involved, and during the time of it’s greatest market power, the price of oil fell an order of magnitude.

Also, if Standard Oil had behaved as some people believe they could have, i.e. hold oil off the market in order to make monopoly profits, we wouldn’t be as dependent on oil as we are now, would we? So we wouldn’t be “in serious trouble” (whatever that means), would we?

Odograph – not sure what your point is, but we still haven’t gotten a positive definition of gouging out of those of you who are certain you know not only what it is, but that it is was going on. Lot’s of table-pounding and arm-waving, but no definition. Until someone can come up with a workable definition, I’m going to continue to believe that it’s, “Any price that forces me to reconsider the choices I have made regarding how I live, i.e. the size, construction, and location of my house relative to my local climate and the distance to work, shopping, and amusements, the means by which I travel between them, the size of my family, etc.” Ability to act on said reconsideration is a factor worth consideration, but I don’t see why we should be concerned about someone who commutes in an H2. In fact, I’d say “Big Wheels” constitute more of the problem than “Big Oil”, but nobody has found a way to squeeze any blood (tax revenues) out of that demagogic turnip. Or, I should say, more blood.

So you’re trying to tell me that in the long run we would all be better off with only one American oil company, based on a temporary price drop and the fact that peak oil would have been delayed?

The higher prices the monopoly would have charged in the long run wouldn’t have impeded economic growth and prosperity?

Breaking up Standard Oil was a bad idea, because they “could have” helped our economy?

I’ll need some serious convincing.

Don’t lay any “certainty” on me Anonymous. I just see some interesting things going on, things that are left out of the more … idealised market arguments.

Ooops, that Anonymous was me.

No, I’m saying that (1) Standard Oil’s market share had already fallen before the antitrust action, so the antitrust action was political grandstanding (analogous to the current anti-gouging demagoguery), and (2) if they hadn’t been broken up and somehow managed to obtain a monopoly (not possible, see #1, but just for argument’s sake) the economy would be so different from what it is today that your previous comment would make no sense.

I believe that you are implying that even if Standard Oil had a monopoly, we would be as dependent on oil as we are in a non-monopolized market when you said, “we would all be in serious trouble”. That isn’t possible if Standard had a monopoly and were behaving the way we expect monopolists to behave. If you mean something else, please explain.

The Standard breakup had either a zero or negative effect. To the extent that their market share was already falling, it had no effect. It had fallen from 88% in 1889 to 64% in 1911, in part because they ignored Texas and Texaco, but also because of Shell and Union. To the extent that Standard achieved some economy of scale and the breakup interfered with that, it was a negative outcome. That seems to be the case since Standard built itself by pushing oil prices lower; kerosene prices fell from $0.58 in 1865 to $0.08 in 1885, and decimated the whale oil industry in the process. Even Ida Tarbell exclaimed they were a marvel of economy. Standard built not only market share but more importantly the market in oil itself by lowering prices, but lost market share to even lower priced producers.

I am not claiming that we would be better off with only one company for any of the reasons you claim; I am claiming that we would have had more than one company without the breakup, primarily because we did before the breakup. However, it is true that if – if! – Standard could have obtained and kept a monopoly (not possible, see above), prices would have been higher, economic growth would have been lower, and Peak Oil would be delayed. Isn’t that what the Greens advocate when they call for nationalization or at least democratic control of energy resources and “sustainable” (i.e., lower) growth? They are the ones who claim that would make us better off, not me.

For evidence, I recommend Gabriel Kolko’s The Triumph of Conservatism, Dominick Armentano’s Antitrust and Monopoly: Anatomy of a Policy Failure, and Burton Folsom’s Myth of the Robber Barons, with maybe a little David Friedman’s The Machinery of Freedom.

Eric-

I’ll take your point that, based on the evidence at the time, government intervention may not have been necessary to weaken Standard Oil. But to say that anti-trust grandstanding is analogous to the anti-gouging rhetoric is a stretch in my opinion.

I’m a student of economics like most here, but I’m also skeptical of those who blindly defend executives and free markets in any industry with simplistic textbook logic.

This article I read this morning fuels my suspicions of oil execs and their intentions, although I still do not believe for the most part that the major players always operate in a shady manner…

Financial Times

BP and Exxon ?inflated US gas prices?

By Toby Shelley

Published: December 20 2005 10:17

ExxonMobil and BP face antitrust action in Alaska as a homegrown pipeline project company accused them of withholding gas from the market and inflating the price paid for gas by US households.

The Alaska Gasline Port Authority proposes to build a line parallel to the existing trans-Alaska oil pipeline and in competition with a gas pipeline project of ExxonMobil and BP.

In a lawsuit filed in the Fairbanks district court, Alaska, AGPA argues that the two oil companies have conspired to refuse to sell natural gas from their joint reserves of 35 trillion cubic feet in Prudhoe Bay and Point Thomson and other concessions on Alaska?s North Slope.

This alleged action has inflated prices and higher prices have ?hurt consumers and businesses throughout Alaska and the rest of the United States?, the AGPA said in a statement. It wants the court to instruct the oil companies to market the gas rather than leaving it in the ground or reinjecting it, or face having their leases revoked.

Tim: “I’m also skeptical of those who blindly defend executives and free markets in any industry with simplistic textbook logic.”

You’re not implying that anyone who uses simplistic logic is blind or naive, are you? Some who strongly advocate free market solutions formed their opinions after many years of real-world experience.

In case you’re wondering, defenders of corporations are generally not hypocritical in our free market beliefs. We are just as opposed to government intervention that benefits corporations as we are to harmful governmental interference.

Wow, the comments in this topic are still going on.

I thought I would clarify how pump prices are set: There are some gasoline stations which are owned and operated by the oil companies. At these stations, the oil company sets the retail price. I believe in all cases the oil companies were very concious of public relations and long term relationships and either held retail margins above wholesale prices even or perhaps reduced them.

Most gasoline stations are either leased or owned by small businessman and operate as franchises or distributerships. In those cases the oil companies are not allowed by law to have any control over retail prices. So in the situations where we saw $5/gallon prices on the news that was almost certainly a local businessman not the oil companies setting the price.

I don’t know how to define gouging, but I think it has to involve markup’s involving multiples of the base price. I don’t see how oil total oil company profits which averaged less than 10% of sales at their peak could be anywhere close…

Doug, let me add just a bit to your explanation.

State attorneys general seem to focus on alleged “price gouging” at the retail level. Many who bash the oil companies were just as upset about “price gouging” at the wholesale level.

Wholesale gasoline prices are more complex than retail prices. Some prices are set directly by the refiner in sales to the retailer. But far more involve a middleman wholesaler, or jobber. Refiner to wholesaler prices are usually established in longterm contracts, with floating prices based on the NYMEX commodity futures price. Direct refiner to retailer prices are generally based on “spot” prices, which are averages of jobber to retailer prices. Basically, then, most gasoline wholesale prices in the U.S. are based either directly or indirectly on the gasoline commodities market.

Although oil companies can slightly influence commodities markets, the markets are much too big to be controlled by them. The truth, which oil company bashers will not accept, is that wholesale gasoline prices are set in a free market.

I rarely defend executives. As they say, “The problem with socialism is socialism, and the problem with capitalism is capitalists.”

It is funny, though, that these guys are withholding natural gas and being accused of a crime. Every Green in the world ought to rise up in their defense, since raising the price of fossil fuels is exactly what they have been demanding through Kyoto and other carbon tax schemes. I’m not going to waste time waiting for that defense, though.

This may be the first case of someone actually applying the Hotelling rule? It’s like finding dark matter. And if we suddenly run out of fossil fuel, as many less-thoughtful Peak Oilers seem to believe will happen, we should thank people like these who keep fuel back for the day when we will need it. However, the markets will punish them in the other two more probable scenarios. On one hand, if they hold it back and nobody follows suit, they will lose market share. On the other, if they hold back on the bet that it will be worth more in the future, and prices fall, they will lose money. That’s a substantial risk, and their only consideration ought to be to get it right for their shareholders. They ought not have to consider whether some politician running for re-election will decide to use them to make a name for himself.

There was an article, Why $5 Gas Is Good for America which got play in “green” circles recently.

Eric H (Anonymous) — “Odograph – not sure what your point is, but we still haven’t gotten a positive definition of gouging out of those of you who are certain you know not only what it is, but that it is was going on. Lot’s of table-pounding and arm-waving, but no definition.”

Really? I believe that there may be some “intellectual” laziness occurring in terms of research effort vs. available information.

Some can’t begin to offer a definition of “price gouging”, yet their own states have statutes for price gouging or similar state level deceptive trade practice laws. Just look up or become familiar with the state statutes, as did JohnDewey (as demonstrated in a previous comment post).

It doesn’t matter if one disagrees with his/her state laws. It just shouldn’t be that hard to cite the available state statute(s) or regulatory language and guidance. But some can’t locate such information, apparently.

Here are my answers for those who are still unfamiliar with the trade policy laws of the States in which some reside.

Note Georgia’s actions (near the bottom of the post) which answer your second point. Was there price gouging, as defined by state trade law, in the State of Georgia during the recent state declared emergency due to problems associated with the hurricane natural disasters? The State says yes, and names and fines the first 15 violators.

There are now 28 states which have laws and regulatory provisions for addressing price gouging during declared emergencies or periods of natural disaster. Arizona should be the next state to adopt a law similar to that of Florida.

Plenty of price gouging definitions exist at this time in many State level trade policies. Some of the definitions are specific, others are still subject to interpretation.

Moreover, the U.S. Department of Energy has a hotline and email web page one can use to identify price gouging and/or price fixing.

DOE’s Gas Price Watch Reporting Form

http://gaswatch.energy.gov/

Status of efforts to create a national definition for price gouging and actions to counter abuses during periods of natural disaster or declared emergencies:

National Price Gouging Law Pursued

Dec. 1, 2005

http://www.azcentral.com/arizonarepublic/business/articles/1201pricegouge01.html

Expect the U.S. Senate to address creation of a national definition and rules for compliance in the forthcoming session of the U.S. Congress.

States with price gouging laws, or executive authority and/or regulations related to price gouging, price fixing, or deceptive trade practice laws during declared state emergencies, natural disasters, or similar conditions:

Alabama, Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia in addition to the U.S. Virgin Islands. (I have forgotten the names of two States. One may be Illinois.)

Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Louisiana, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia have laws that specifically address price gouging in the event of a declared emergency. Other states may exercise authority under general deceptive trade practice laws depending on the nature of the state law and the specific circumstances under which price increases occur.

Examples of State trade practice laws regarding price gouging:

State of Virginia – Role of the Virginia Attorney General with regard to gasoline pricing during disasters

http://www.oag.state.va.us/Protecting/Consumer%20Fraud/gasoline_education_website.htm

“The price gouging statute requires the Virginia Attorney General, and other enforcement agencies, to consider whether post-disaster prices of a supplier grossly exceed the prices the supplier charged for the same goods or services during the ten (10) days immediately prior to the disaster. The statute also requires consideration of whether the increased costs are attributable solely to the increased costs of the supplier. The Attorney General is prepared to act if an emergency is declared or if a determination is made that our competition laws are being violated.”

State of Arizona Attorney General- What is “price gouging”?

http://www.azag.gov/consumer/gasoline/gas.html

“Price gouging is generally defined as a situation in which a few merchants attempt to take advantage of consumers seeking goods or services that are in short supply. Shortages of various goods or services can occur for a wide variety of reasons, often during emergency situations such as a pipeline break, fire, flood, hurricane, earthquake or terrorist attack. More than half the states have price gouging laws, but Arizona does not. Most states laws define price-gouging as a price increase from any increase (0%) up to 25% increase above the normal price after a state of emergency has been declared by a governor or the president. These laws are usually only in effect for limited periods of time, and do not apply to general price increases.”

State of Florida – Price Gouging Frequently Asked Questions

http://myfloridalegal.com/pages.nsf/Main/5D2710E379EAD6BC85256F03006AA2C5?OpenDocument

Further — “Sec. 501.160 (1)(b) It is prima facie evidence that a price is unconscionable if:

2. The amount charged grossly exceeds the average price at which the same or similar commodity was readily obtainable in the trade area during the 30 days immediately prior to a declaration of a state of emergency, and the increase in the amount charged is not attributable to additional costs incurred in connection with the rental or sale of the commodity or rental or lease of any dwelling unit or self-storage facility, or national or international market trends.”

State of Georgia – Emergency Price Controls

http://www.georgia.gov/00/channel_title/0,2094,5426814_39110281,00.html

State of Georgia – Price Gouging

http://www.georgia.gov/00/article/0,2086,5426814_39039081_38232662,00.html

“Although competition and demand drive prices in our free-market economy, during a declared state of emergency Georgia law prohibits businesses from taking advantage of the situation to engage in price gouging (O.C.G.A. Sections 10-1-393.4 and 10-1-438). Under a state of emergency, state personnel and equipment may be used to help local governments, and the laws price-gouging provisions automatically go into effect.”

“Businesses may not sell any goods or services necessary to protect your health, your safety or your property at prices higher than the prices at which those same goods or services were offered before the declaration of a state of emergency. This can include food, lodging, gasoline, propane gas, lumber and other supplies. Nor may a business raise the price of supplies or services for the purpose of salvaging, repairing or rebuilding structures damaged as the result of a natural disaster. Increases are only permitted that accurately reflect increases in the cost of new stock or the cost to transport it.”

“The Governor is empowered to declare a state of emergency in response to or in anticipation of a natural disaster or a national security emergency. All counties in the state are covered, unless the executive order declaring the emergency is limited geographically to certain counties. The Governors Office of Consumer Affairs has the authority to investigate allegations of illegal pricing, with the assistance of the Georgia Emergency Management Agency (GEMA) and the Georgia Bureau of Investigation. Violators can be fined from $2,000 to $15,000 per violation.”

“If you believe you have been a victim of price gouging during a declared state of emergency, you may file a complaint with the Governors Office of Consumer Affairs.”

State of Georgia – Gasoline Price Gouging Complaint Form

http://consumer.georgia.gov/00/article/0,2086,5426814_39039081_41744913,00.html

Congressional Action in 2006

Do you believe that the Congress will draft and pass a definition for price gouging to include specific federal agency responsibilities for insuring that such behaviors during emergencies and natural disasters will not be tolerated?

Here’s a hint from a key U.S. Senator.

U.S. Senator Pete J. Domenici – position on price gouging

September 6, 2005

http://domenici.senate.gov/news/record.cfm?id=245398

“Price gouging laws should be vigorously enforced on the state level, and if the federal government can help it should. The Federal Trade Commission is not specifically subject to the jurisdiction of this committee, but any oil company that is price gouging will find themselves in our witness chairs where they will be held accountable,” he said.

U.S. Senator Pete J. Domenici – follow up position on price gouging

September 13, 2005

U.S. Senators Pete Domenici and Jeff Bingaman, the chairman and ranking member of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, today called on the Federal Trade Commission to use “heightened vigilance” in monitoring and investigating possible gasoline price gouging and energy market manipulation.

The New Mexico lawmakers, with the bipartisan membership of their committee, today sent a letter to FTC Chairwoman Deborah Platt Majoras addressing recent gasoline prices escalations.

“It is important that the federal agencies entrusted with responsibility for consumer protection, such as the FTC, be on heightened vigilance for such behavior, and communicate that vigilance to both the industry and consumers,” Domenici and Bingaman wrote Majoras.

“The recent trend of rising gasoline prices and their immediate increases in the wake of Hurricane Katrina has elevated concerns about price fairness,” they said. “As American consumers face potentially unprecedented retail energy prices, many are concerned about the possibility of market manipulation and price gouging.”

Examples of State level actions and inquiries:

States Moving Against Gas Price-Gougers

April 8, 2005

http://www.consumeraffairs.com/news04/2005/gas_prices_ags2.html

State of Georgia – Governor Perdue Announces 15 Gas Gouging Settlements

http://consumer.georgia.gov/00/article/0,2086,5426814_5684686_44105245,00.html

Available FirstGov Search news releases and commentary from government officials on the subject of price gouging

http://www.firstgov.gov/fgsearch/index.jsp?mw0=price+gouging&ms0=+&mt0=all&st=AS&rn=2&parsed=true

1,818 different news releases and commentary available for review. Over 100 pages of links.

Example of a Disaster Official Warning about Price Gouging

Disaster Officials Warn Against Price Gouging

June 1, 2001

http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease_print.fema?id=6869

“After surviving a natural disaster, already vulnerable victims also may become targets of predatory practices, such as price gouging.”

“Price gouging occurs when a supplier marks up the price of an item more than is justified by his actual costs. Disaster victims are particularly susceptible because their needs are immediate and they have few alternatives to choose from.”

“Because of this, the state of Iowa has a separate section in the Code of Iowa addressing the subject. While the code goes into great detail, it can be simply summarized by the following quote from the law:

“The charge of excessive prices for merchandise needed by victims of disasters is hereby declared to constitute an unfair practice.””

“Iowa code also says that price gouging will be presumed if there is a substantial increase in the price of an item immediately following a disaster.”

“There are 19 counties covered by President Bush’s disaster declaration for Iowa. Anyone suspecting instances of price gouging in those counties should report it to the Iowa Consumer Protection Division at (515) 281-5926.”

Jim Hamilton,

You still haven’t attempted to answer any of my five questions from December 16, 2005, 2:33 pm:

1. Did the refining capacity shortfall cause all or most of the gasoline pump price increases?