With world oil supplies already stressed by production cutbacks in Nigeria and Saudi Arabia, worries that the Israeli conflict might further disrupt oil shipments have produced new price highs. How does that affect the prospects for an economic downturn?

I have long maintained that the big economic consequences sometimes observed to follow oil price shocks result if labor and capital become idle when demand in certain key sectors drops precipitously. A prime example is the U.S. automobile market, whose domestic manufacturers have historically been very reliant on sales of the less fuel-efficient models.

|

It looked possible that we might see a replay of that familiar historical sequence last fall, as U.S. gasoline prices shot up quickly and car sales and consumer sentiment plummeted. But when prices came back down just as quickly as they had gone up, sales and confidence recovered, and the economy managed to avoid going into a recession.

One of the reasons why, in the absence of such demand disruptions, the economic effects of energy price increases should be manageable can be seen from the following argument. Suppose that somebody was previously paying x dollars for their energy bill, and energy prices then go up by y percent. One option for that person is just to go on doing everything pretty much as they were before, spending now xy more dollars on energy and reducing saving or spending on other products by only that amount. With the U.S. currently using about 7.5 billion barrels of oil each year, a $10/barrel increase amounts to $75 billion, which represents a little over half a percent of our $13 trillion GDP. For comparison, an economic recession typically results in a loss of somewhere around 5% of GDP. Something more than the direct loss of purchasing power is needed to produce a full-scale recession.

|

And doing things in about the same way as before may not be a bad description of how many U.S. consumers are currently behaving. I commented last month that a $3.00 price for gasoline seemed sufficient to keep U.S. gasoline demand from growing. However, the data released since then suggest that gasoline demand may have popped right back up, despite rising prices.

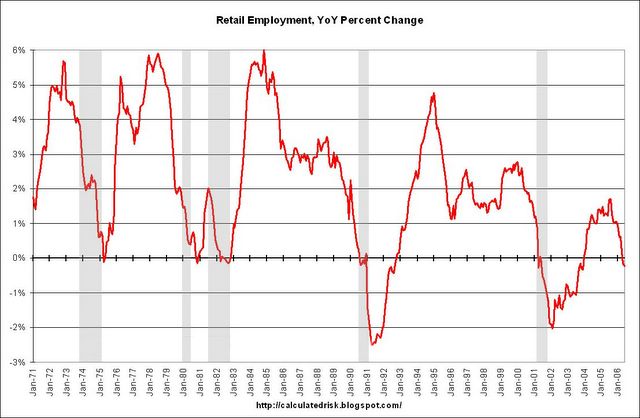

Even if we are so far avoiding a replay of big disruptions in spending patterns this time around, giving up a half-percent of what you had, and then another, and then another, is surely going to take a toll on household balance sheets, corporate profit margins, and the trade deficit. The worrisome drop in retail employment noted by Calculated Risk may be one manifestation of that pressure. And I have no trouble imagining that consumer sentiment series making a dramatic plunge downward at any time.

|

Continuing to do things more or less as we had been was not an option last fall, or in the other historical oil shocks that led to recessions, when the physical nature of the supply disruption required, by hook or by crook, some significant changes in energy use patterns. Nor will doing things as before continue to be an option if the current military conflict in the Middle East does end up leading, for example, to a significant disruption in Iranian oil shipments.

Technorati Tags: oil,

oil prices,

oil shocks,

macroeconomics,

recession

Is there any good up to the minute data on what is happening with the overall mpg of the US auto fleet? What about things the trucking sector is doing to cut energy consumption? One thing people have not pointed out is how flexible and competitive trucking is relative to the oil shocks in the 70’s when the industry was regulated.

A novel:

I was confused by the banking investment in a copper mining town when the mine was shut down.

Then the Marble group came to power. I watched as the commodity bubble was inflated on queue. Surely Allen Greenspan wasn’t a pimp.

I tell myself it is a paranoid delusion that the world economy could be one big project. How could big money actually be executing a plan to overthrow the government of the United States?

Then I watched as the presidency was won under dark circumstance, made possible by a constitutional breach by the Supreme Court.

How could a flawed country clubber from Crawford Texas ascend to the presidency of the greatest country the earth has known?

I lost $ 500,000 to my broker, finality investments. I watched my short position deteriorate as the recently hired manager of the largest mutual fund, Drake, a former hedge fund operator , pump the price of Relp Lodge Mining 22% three days before the company announced an 80 % miss on earnings.

For at least two years, the world economy has been shrugging off the Fed’s terrible fine-tuning of inflation. So the problem is in addition to the Fed’s policy, it can shrugg off an oil price of $80 and even $100 (I understand the latter is close to the inflation-adjusted oil price of 1980). Actually, the real problem is not the prospect of higher oil prices but the reasons for this increase, in particular the ongoing war against terrorists and Iran (it’s not an open war yet but it is becoming clear that it is a question of time). As long as you don’t develop scenarios for this war you cannot analyze how it will affect the world economy–whatever its effects on oil prices. If I had to build those scenarios, among other things, I would assume that the Fed will reduce its interest rates once Israel (and US?) hits hard Lebanon, Syria (and Iran?). Have a nice summer (I will try to enjoy my winter break).

Stick to funds that invest in large caps.

Money supply has reversed course and is re-accelerating again. M2 growth has been accelerating erratically but definitely for seven weeks now.

Considering the pessimism out there now, and all the bad news from the Middle East,now is a good time to add some money to equities. I did so on Friday, will do more if M2 continues accelerating. More news on that score on Thursday.

One of the most fundamental dogmas of economics is that people’s behavior depends on price alone. $3 gasoline due to a shortage should not produce different behavior than $3 gasoline due to speculation in the commodities market. However you allude to the possibility that this is not true:

“Continuing to do things more or less as we had been was not an option last fall, or in the other historical oil shocks that led to recessions, when the physical nature of the supply disruption required, by hook or by crook, some significant changes in energy use patterns.”

This is not the case today. Oil is in plentiful supply, it’s just very expensive because people are afraid it may become short. But “continuing to do things more or less as we had been” is an option now because there is no actual shortage. And indeed we seem to see different behavior today than we did last year with almost the same prices.

How would you explain this? Is consumption behavior different when high prices have cause A versus when high prices have cause B? How do you factor that into your economic models?

Great observation, Hal (as always). One point I was trying to make is that, when all is done, the outcome must be a drop in oil use if the cause was a disruption in supply, whereas that need not be (and has not been) the case with the response to demand-induced price increases.

As for the mechanism whereby that drop in oil use would occur, I would add to your point that it is not simply the current price, but also the expectation about future prices and income, that should influence current behavior. On that score, there may be a role for the changes in consumer sentiment that I’ve been referring to. I believe there is a strictly neoclassical story one can tell for this, in which the plunge in spending and consumer sentiment is a rational response to some shocks and not others, given that everybody understands the equilibrium outcome has to be different, and so workers rationally and correctly perceive the dangers of some job and wage cuts in response to certain shocks. In this view, it is not the plunge in consumer sentiment that causes the problems, but the plunge in sentiment simply rationally anticipates the problems to come.

However, I am not convinced that this is the only way to read events, and do not rule out the possibility of an emotional component to consumers’ reactions as well.

But what I do know for certain, as I wrote in the original post, is that if there is a physical supply disruption, something in the pattern of response has to be different.

An additional $75 billion/yr expense increase in oil might not seem like that much by itself.

But if history is any lesson, when the housing market is in full decline, home equity extractions will not only go to zero but overshoot and become negative. This will suck something like $500 billion of consumer spending out of the market.

Add this to energy price increases for $80/barrel, and you’ve got a ~4.4% drain on GDP. Yikes.

I’m not sure the explanation about expectations of future prices really holds water. You’d have to go back to last fall and look at the price structure of oil futures, and compare it with the price structure today. AFAIK the overall pattern has been much the same for at least the past year or so: a small increase for about a 12-18 month window into the future, followed by a gentle decline over the next several years to a level somewhat lower than current prices.

My guess is that people have gotten used to the idea of $3 gas and it is not as shocking as the first time it happened.

Hal, in equilibrium both the price of oil and the aggregate level of income would adjust to exogenous events such as (1) an increase in Chinese demand for oil, or (2) a decrease in the production of oil from Iran. I was raising the possibility that the income responses could be bigger for (2) than for (1), even if the price responses might be similar.

Clearly, if the US uses 40% of the world’s gasoline than changes in US demand will affect the world price of crude. On the whole, $3 gasoline, plus higher interest rates, have so far not dented transportation fuel demand from an expanding US economy.

As per last week’s DOE numbers, gasoline use is up 1.7% YOY while distillates (diesel) use is up 3.3% YOY, while overall demand is down -1.6%. However, transport (gasoline & diesel) account for 13.68 mbpd while total demand is 20.82 mbpd or about a 7 mbpd difference. This is likely the demand for crude for manufacturiing and stationary power, which due higher prices is being rationed or substituted using hydro-electric, nuclear, coal or natural gas, for example.

So $3 a gallon gasoline is not having an effect on transport use of consumers as their are few alternatives, while $75-80 crude is having an effect on overall industrial demand, but because the numbers are not broken down we do not know from where those efficiency gains or demand destruction are coming?

Carnival of the Capitlists

This week’s Carnival is up. Some of the highlights: The Skeptical Optimist points out that the national debt really is necessary for decent growth. Hmm, seems to me I’ve heard that argument made somewhere before. Econbrowser suggests that while the…

If the amount of energy entering the economy is stable, then changing the price just changes ownership. Increase the price of energy to Western consumers and the owners of oil profit. What do those owners do with their profits?

They can also buy goods and services, just as would the Western consumers. They can also invest in capital goods and financial instruments that in turn continue to produce goods and services. So long as they don’t just burn the money….

The only thing that changes is the ownership.

In the case of real declining EROEI, so long as output is stable, prices will increase but consumption will shift to the production of energy. That is, high prices go to pay for drill rigs, seismic surveys, drill crew labor, etc.

Hey… I wrote about the drop in retail employment on one of these blogs months ago. I’ll look for it.

I found it. It is right here.

https://econbrowser.com/archives/2006/06/indications_of.html

If you want to see another indicator, take a look at the retail employment trend at BLS. It’s headed down. Usually this is a harbinger of recession.

Posted by: vorpal at June 4, 2006 10:41 AM

So Goldman-Sachs and CR can eat my shorts. 😉

Links and Minifeatures 07 17 Monday

RINO Sightings Recommended: Armies of …

Demand for crude has continued as it always does because consumers have decided to cut other discretionary spending. I think we’re seeing cutbacks in retail and dining. (Check out SBUX and CAKE’s recent earnings reports.) This is why higher energy prices act like a tax on people. People still pay for energy. Got to have it. But they’ll cut back on other things. This is also why higher energy prices don’t creep into the core CPI. As energy prices rise and folks spend less on discretionary items, inventories on shelves rise…

Cheesecake coupons coming your way!

“”This is why higher energy prices act like a tax on people. People still pay for energy.””

Sorry, I have to take exception to refering to high energy prices as a tax. They are not. They are either a cost of production or the price of consumption. Need does not change that. People need to drive if their are no viable public transport alternatives. Higher automobile prices are also not a tax, they are a purchasing choice consumers make. People need to live somewhere. Higher rents or housing prices are also not a tax. They are a lifestyle trade-off. Rent or buy? Live closer to work, commute further. They are a set of trade-offs that limit disposable income and what it can buy. But they are not a tax. I hate to belabor the point, but the higher energy prices are like a tax has been too widely used and it is wrong. Thanks.

Fed Watch: Living on a Knife Edge

Tim Duy with his latest Fed Watch: Living on a Knife Edge, by Tim Duy: Big, big week for monetary policy. Today, we get the PPI figures. Tomorrow, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke marches up to Capitol Hill for his Congressional

James

Are you not taking your figures gross not net?

The US is a significant oil and gas producer (still) and the Canadian economy (which arguably is simply part of the US economy post NAFTA) even more so. Alberta is booming, high gasoline price at the pump or no– a lot of that activity will be fed by exports of goods and services from the USA.

The US is also home to some of the world’s leading oil service companies, which export all over the world. And much of that increased revenue to oil producing countries finds its way into US Dollar securities (lower interest rates, and also more activity and revenues for US investment banks and hedge funds).

So a rise in oil prices *stimulates* the US economy in a number of ways.

Obviously, since the US is a net oil importer, the overall effect is negative, but the multipliers are pretty positive, for certain sectors of the US economy.

“Statistics Canada said overall exports decreased by 0.2 per cent in May to $37 billion, while imports fell by 0.8 per cent to $32.93 billion.

Falling exports of energy, agricultural and fishing products, forestry products, and machinery and equipment outweighed gains made in shipments of industrial goods and materials, automotive products and consumer goods.

Import declines were seen in automotive products, energy products, forestry products and other consumer goods.”

Source:http://www.cbc.ca/story/business/national/2006/07/12/trade-surplus.html?ref=rss

Canada’s made at home oil boom in Alberta is not fuelling massive imports from the US of any kind as far as I am aware? Canada is also a successful exporter of oil field technology and workers, and therefore requires very little from the USA, although of course some US companies are also active in Canada as well as other foreign multinationals like BP or Shell.

With a healthy trade surplus, also in manufacturing and other industries, and not just exports of oil & gas, there is not a lot of evidence that this is stimulating the US economy viz a vie exports of goods & services to support growth in Alberta.

Nor are those exports being recycled into US treasuries as far as I am aware as the Canadian dollar is appreciating?

And yes, even post-NAFTA, Canada is not a part of the USA. Reliant on trade, yes, an extension of the US economy, no.

Assuming my analysis is correct (the “Petrodollar” theory), higher energy prices do act in some ways like higher taxes.

Like higher taxes, people work as hard or harder and see less return on they efforts since more of their effort is going to support some sheik’s harem or buy airline tickets for terrorists. Ergo, they tend to work less hard.

This is a second order effect but still there.

MrBill

The multiplier effects with the Alberta economy would be limited to exports of services (eg american investment banks raising capital to invest in Canada) and also exports of oil drilling services, (the world’s largest oil services cos are mostly American– Haliburton, Schlumberger etc.), and capital equipment.

What you have to look at is where the Canadian oil industry is sourcing its drilling equipment, and conversely where it is shipping its oil and gas.

The economies have become so interlocked post NAFTA (they are the largest source of imports to Canada, and the largest destination of Canadian exports) that I think it is reasonable to say that they are practically one economy. note *not* one country. Agreed that GDP is not measured that way.

It appears that the Middle Eastern sellers of oil have also increased their US dollar denominated assets (albeit by less). I agree that is likely not what is happening with Canadian oil exporters.

Thanks. Appreciate the comments.