Can high-flying stocks be reconciled with an inverted yield curve? David Rosenberg of Merrill Lynch, via Felix Salmon and Business Week thinks “it is highly doubtful that both asset classes can be getting the story right.” But here’s one scenario under which both markets in fact might be telling the same story.

|

The nominal yield on 10-year Treasuries is down 60 basis points since the beginning of July. The yield on inflation-indexed Treasuries has dropped about half that much, suggesting that the decline in the nominal yield is due in equal parts to a decline in inflation expectations and a lower real interest rate.

|

One could take those drops as pretty dire. Some of us had believed that a severe economic downturn might be necessary in order to bring inflation down, and slowing economic growth is also the most plausible explanation for declining real interest rates. And if one were looking for additional reasons to be pessimistic, certainly there’s plenty to draw on in some of the recent housing data, e.g.,

[1],

[2],

[3].

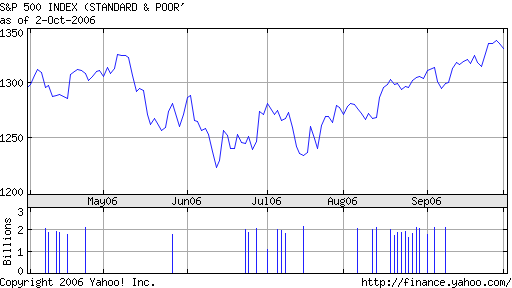

But one datum that clearly does not fit that gloomy scenario is the stock market– the broad market indexes have been charging up even as the grim housing indicators have been coming in.

|

Of course, stock prices reflect both expectations of future profits as well as current interest rates. A lower real interest rate means that the present value of future earnings has increased even if the earnings themselves are no higher, because future flows are discounted less. Furthermore, the stock market has always exhibited an aversion to inflation as well. Hence, even if investors’ forecasts of future profits had not improved, one might still expect to see stocks appreciate as a direct result of a lower real interest rate and lower expected inflation. In other words, part of the stock market rally could be viewed as the logical companion of that for bonds. But the magnitude of the stock market surge seems too large to attribute to this alone, and certainly is grossly inconsistent with the assertion that investors believe the U.S. is about to enter a recession.

|

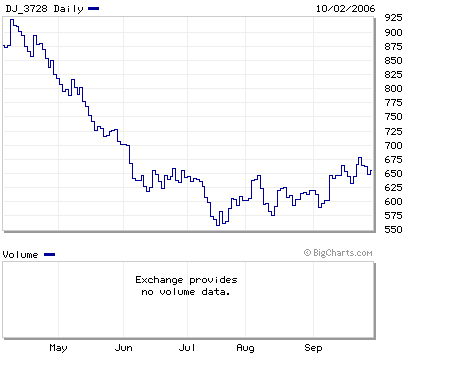

Of particular interest is the equity performance of U.S. homebuilders, such as the Dow Jones U.S. Home Construction Index. This, too, has actually rallied since July.

To be sure, home construction stocks were clobbered most dramatically in the 3 months before July, as investors anticipated– correctly, it turns out– the miserable housing stats we’ve all been seeing come in over the last several months. But, disappointing as these numbers have been, what’s come in during the last two months is apparently no worse than the market had already discounted. Investors seem to think that this might be as bad as it’s going to get.

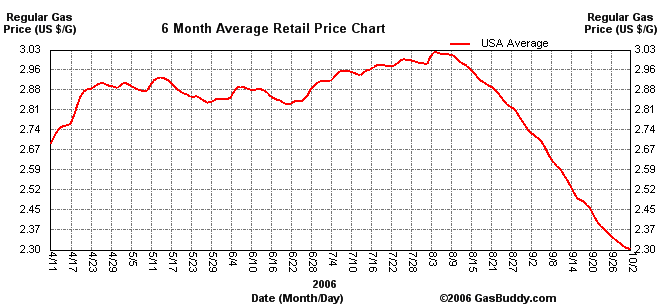

Apart from the hopes of stock market investors, is there any rational basis for this optimism? As we’ve noted here previously, there are a few glimmers of positive among the torrent of negatives, namely falling mortgage rates, a hopeful uptick in the latest pending sales figures, and rising consumer confidence buoyed by plunging gasoline prices.

|

Which brings us to a related seeming contradiction discussed by Tim Duy. Current fed funds futures and option markets are betting that the fed funds rate will be down to 5% by next spring. And yet, in public statements the Fed seems to be communicating that, if it makes any changes, it is more likely to be toward higher rather than lower rates.

Well, here’s a story that I believe could reconcile everything. The housing slowdown is significant, real, and upon us now, but this is as bad as it’s going to get. Inflation numbers will begin to look better, allowing the Fed some breathing room to bring rates down slightly, averting a complete meltdown in housing. We get slower real economic growth, the biggest burden of which is borne by homebuilders. But the benefits of taming inflation bring some cheer to the rest of Wall Street and perhaps Main Street.

In other words, markets seem to believe that Bernanke is going to pull off the soft landing after all– slower real growth for sure, lower inflation, but no recession.

On this, the markets may or may not prove to be right. But I don’t see any other way to try to tell their story.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

Federal Reserve,

soft landing,

stock market,

housing,

yield curve

How would you reconcile the message from the currency markets, the U.S. dollar with the behavior of the stock and bond markets?

If there is a slowdown in the economy wouldn’t the U.S. dollar be expected to fall?

Has that fairy tale flavor about it all right: stocks (owned increasing by the wealthy few) representing products and services access to which is increasingly limited to these few, (dwindling few) owners/shareholders, have rising price tags from fairy intervention in the absence of real demand. The same fairies intervene to ensure a resumption in housing prices (once “the breather” is over) in the absence of qualified buyers.

What would we do without fairies?

Not much.

WOW!!!!!!!!!!

All I say to this is:…

The future’s so bright, I gotta wear shades.

Some very good points.

One of my main blanket criticisms with this view [soft landing] is it never seems to take into account interactions, and the fact that we have a closed system.

For instance, adjusting ARMs will cause foreclosures (adding downward pressure on home prices) and at the same time make a significant number of consumers broke, reducing their spending. The cessation of home building and slow down in sales volume will put a lot of people out of work, who also will have to stop spending [hundreds of thousands of realtors must effectively already be out of work].

These things will clobber corporate profits badly, while the home market will get worse.

Right now FCBs are buying a high level of non-Treasury government securities, possibly trying to float the housing market. But it will be impossible to capture the old magic, due to exhaustion and stricter new lending guidelines.

And what of inflation? Well, core inflation is as strong as ever. It sure is funny how the market decided to focus on comprehensive inflation metrics as soon as energy started falling! But the Fed works off core inflation. Hence you have Poole basically saying “we’ll attack inflation over concerns with output“.

So, I tend to agree with you. The market still is predicting soft landing… whether it is likely is another story.

Gavin, I don’t have a clear prediction for what the effect on the dollar should be. A lower U.S. real interest rate would suggest dollar depreciation, lower U.S. inflation might mean dollar appreciation. Slower U.S. output growth should reduce the trade deficit, easing some of the need for long-run dollar depreciation. But I’m still fundamentally puzzled about why we hadn’t seen more dollar depreciation already, independent of the latest developments, as a response to that trade imbalance. If it has something to do with the “safe haven” theory for international capital flows, then the story above might be viewed as making the U.S. dollar a more favorable currency in which to hold assets.

This is not a conundrum. Long-term interest rates are being depressed by Asian central banks & oil states’ recycling. This liquidity(only different from Fed-supplied liquidity in that it is supplied on the long end) is stimulative to the stock market.

Thanks for your views on the dollar professor.

I wouldn’t have believed that we could have a soft landing with one of the sharpest declines in real estate sales. But after looking at the experience in the U.K. which has had a bigger housing bubble than the U.S. I think we could avoid a hard landing.

The yield curve was inverted in the U.K. (possibly because of the legal requirement that pension funds there had to buy long term bonds rather than an indicator of a recession), consumer spending slowed down sharply but there has been no recession.

The FED has pushed us out of the plane so I just hope we land without killing anyone. What is a soft landing is in the eyes of the unemployed or bankrupt?

Aaron,

The key to coming out of this slowdown is not actually real estate or the consumer having more money to spend. Congress gave producers the extension on the tax reductions that they needed so they are poised to bring products to the market.

Once again the one fly in the ointment could be the FED. Because their indicators are backward looking, around 6 months behind, they will be seeing signs of inflation. Will they resist the urge to renew the fight?

James,

When you talk of dollar depreciation I assume you are talking about depreciation against other currencies rather than a decrease in real purchasing power of the dollar? Is this correct?

Dick, yes, I understood Gavin to be asking about the value of the dollar in terms of other currencies. The value of a dollar in terms of goods and services is of course what the comments about inflation in the original post addressed.

Dr. Hamilton, I forget where I got this idea from–I think from CNNMoney (OK, not a very highbrow source). Is it possible that speculative money is just cycling from housing (back) to the stock market, thus propping the latter up?

Over the past month bond yields fell about 75 basis points. Regression analysis implies that the relationship between bond yields and the s&p 500 p/e is roughly one-to-one — a 100 basis point drop in yields generates a 100 basis point rise in the market PE.

At around a pe of 15-16 this relationship implies that a 75 basis point rally should generate about a 5% rise in the stock market.

On this basis there is no reason to think the bond and stock markets are discounting different things.

Except earnings have to come from somewhere, and bond yields do not fall in a vacuum. Under normal circumstances, bonds behave like this when a severe slowdown is on the way. Sever slowdowns are associated with drops in the denominator of that P/E ratio, and markets do not trade on past earnings, but on predictions for the future. As a result, you have to believe that bonds are dropping dur to a slowdown that moves *just so*, in a way that does not put an undue crimp in earnings.

Our host calls it a soft landing; I call it a Goldilocks economy. It is not how I am betting longer term, but for the moment I have October index calls — since I believe the markets often look at the data a little crosseyed.

It’s actually quite simple to tell the story. This is the sucker’s rally that almost always occurs months prior to a recession actually hitting. Nouriel Roubini discusses this on his blog http://www.rgemonitor.com/blog/roubini/

wcew — if you look at the data while there is a strong correlation between the market and earnings,the correlation between the change is eps and the change in the market is essenially zero –meaning is is almost perfectly random.

Yet, the correlation between the change in the market pe and the change in the market is nearly 0.9.

this mean that if you make a prerfect forecast of the change in earnings it is of no help in telling you what the market will do. But if you can be right about the change in the market pe you have a 90% probability of being right about the direction of the market.

Maybe so — my alpha is still not significant at .05. That said, you ignored the meat of my critique: if earnings drop with the economy, what good does a higher P/E do?

This puts me in the mind of very longago market wisdom, back in the day when economic cycles were much harder than the last decades. Simply, it was to go long when P/E’s were at their highs, since that would happen when E’s were in cyclical troughs, and sell at the lows, with corresponding earnings peaks.

FD, I have October index calls (great move today, if nothing else), but I am getting ready to underweight or even go short, depending on the data.

Just a thought – Are long-term rates being impacted by the slowing housing market? If Asian banks were recycling large amounts of dollars back into Fannie and Freddie bonds, CMOs, ABSs and other obligations related to housing, and the issuance of those obligations have been substantially reduced (less home sales, equity extractions, etc.), then where do the excess dollars go? Wouldn’t some of that money get redirected into US Treasuries? And since the foreign banks are, to some extent, price insensitive (being more concerned with exchange rates), could this not be affecting the bond market “story”?. In other words, are redirected dollar flows temporarily pushing down long-term rates?

seems like a good snapshot of “The Market moves to make people wrong.” The Bear case is no longer novel, rather a little long in the Tooth.

I’d think we’re going to see some Capitulation Buying coming in the not too distant Future. Til’ then, one has ride this trend.

“The Market moves to make people wrong.”

should be: “…the Most people wrong.”

if you look at the USD over the year to-date, it got hit very hard in the late-March, April, to early-May timeframe. that’s exactly when the Helicopter Ben/commodity boom/inflation meme was running rampant through the capital markets.

then right around May 8th, that meme took a running leap into the dustbin of market history as the “uh-oh, housing’s gonna kill us” meme took over. the price chart of gold tells the story pretty well — the precious yellow soared in March and April and then peaked on May 11th right around $720 as the Helicopter Ben meme reached its apex.

capital market flows are critically important at the moment – Dr. B is right about the surplus of global savings, which has no excellent place to go. maybe it’s not that the dollar is so wonderful, but just that all the alternatives have taken two steps backwards.

As the oldest society on earth (with a labor force that’s mathematically certain to shrink steadily for 18 yrs minimum), Japan offers poor investment opportunities, the EU is a lousy substitute for the once-trusty DM and while China’s a dynamic engine of human ingenuity, the political system isn’t as trustworthy or transparent as most investors might like.

all that said, while US interest rates look low relative to our past 30 years, in a global context, the US has HIGH interest rates not low rates. THAT’s the impact of the trade imbalance at work, IMHO.

last, it’s monetary liquidity that makes the stock market go, not earnings – go back and look at the mid-to-late 1980s for example. earnings make individual stocks go up and down, but in the aggregate the stock market is relatively insensitive to earnings.

without hard proof, I think the digital age is contributing at the margin to the surfeit of savings and excess liquidity . . . . ’cause globally, places like China that once might have sunk enormous sums into landline telecom now can jump that white elephant and build out cheaper cellular systems, and in the info/internet era new technologies can be shared (or stolen?) instantaneously, and ERP type info systems ought to help avoid building lots of infrastructure, heavy plants and stuff that isn’t needed in the first place.

anyway, buy stocks. with a short term glut of oil and rates coming down and the markets starting to look ahead to the first Fed ease, stocks are going up. it’s a bit like 1998 that way – you’d think that a bad economic shock or two or three would really hurt stocks, and at first when it stings bad stocks go down, but when the initial pain fades, the economic drag puts the onus on the central banks to ease off a bit, and then the animal spirits of capitalism start raging again.

Great Britain had a bigger housing bubble than the US, and yet it (so far) has experienced a soft landing. Unless this anomaly can be explained, it is quite plausible that the US will, also, experience a soft landing.

I have a guess as to a possible critical difference between the US and UK. My guess is that the US housing market, but not the UK’s, was rife with speculators who bought houses without any thought of living in them. In addition to the speculators were people with one home who decided they could use a second home, but their decision was primarily motivated by the sharp increase in housing prices and the availability of mortgage financing.

If my guess is right, we have in the US a substantial quantity of homes that were built not for people who wanted to live in them but for people who were speculating on the housing market. How will these homes be filled up with people who want to live in them? Only by such people selling their existing homes and moving in. But if there is a glut of X homes, and it can only be filled if X existing homeowner-occupied homes are sold, then the X cancels out and there is no relief on the downward pressure of home prices. Or have I miscalculated something?

from http://blog.myspace.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=blog.view&friendID=51443639&blogID=176471907&MyToken=0f2296af-9ffd-48a3-bdeb-372a2e203c9e

Of course, when I hear comments like this, I’m immediately reminded of Q3, 2000, when, despite a severe crash in the Nasdaq, despite an inverted yield curve, investors intently bid up the S&P 500 to all-time closing highs. Today we have something similar: a severe home builder crash, an inverted yield curve and a Dow Jones Industrial Average bid up to new all-time highs. We also have a host of soft-landing advocates. Back in 2000, economists and analysts ardently promoted the soft landing scenario. (of course, we all know how that “soft landing”ended up).

For your reading pleasure, I dug up a bunch of articles to show just how “current” the soft landing criers of Q3 and Q4 of 2000 seem. Time will tell if today’s experts are prematurely calling for a soft landing once again:

Dec, 2000 by Charles R. Yengst

It Looks Like We’re Getting The Soft Landing We Were Hoping For

The question is; are we going into a period of soft landing or a death spiral toward a deep bottom in the market? As an observer of the North American economy for nearly 30 years, I would have to venture that this slowdown is one of the most gentle I have seen.

Sept, 2000

The U.S. Economy is headed for a soft landing – predict economists

A growing number of analysts are convinced that the Federal Reserve has administered the right dosage of interest rate increases to slow economic growth just enough to keep inflation at bay while averting a recession. Recent economic reports provide the evidence that growth is slowing down, and that a slowdown can be sustained for at least the year ahead without an acceleration of inflationary pressures.

Sep 11, 2000 by Avrum D. Lank

`Soft-landing scenario’ plays well for economy

The soft-landing scenario is playing as scripted,” Bruce Steinberg, chief economist for Merrill Lynch & Co., wrote recently.

“Our panel sees a soft landing for the economy,” Richard B. Berner, chief U.S. economist for Morgan Stanley Dean Witter, agreed. Berner made the comment while releasing a survey of members of the National Association for Business Economics, of which he is also a vice president.

Aug 24, 2000 by Ray Carter

Bank One economist predicts `soft landing’

(Anthony Chan, managing director and chief economist for Banc One Investment Advisors) believes the lack of action by the Federal Reserve opens the door for a “soft landing” in the economy that will slow the rate of growth.

Jul 21, 2000 by Philip Thornton

Greenspan raises hopes of soft landing

Wall street gained ground last night with both shares and bonds posting strong gains after Alan Greenspan, the man charged with setting interest rates, hinted he was happier with the state of the economy.

it’s monetary liquidity that makes the stock market go, not earnings

Anarchus,

You have to be kidding. Was the market surge during the 1990s a liquidity move?

I know of no time in the 20th or 21st Century that had more liquidity than the 1970s yet the DJI was about 800 in 1970 and it was about 800 in 1980.

Sir Anon:

Nope, not kidding.

In point of fact, the 1990s support my case quite well . . . . . the stock market (using the S&P 500) bottomed at 304.00 @ 10/31/90. EPS for the S&P 500 turned out to be $21.34 in calendar 1990. Calendar 1991 earnings were $15.91 per share and calendar 1992 earnings were $19.09. Given the declining earnings, you’d think maybe the market might not have done much, then, but because the Fed began easing monetary policy aggressively late in the fall of 1990, the yield curve went to an extremely positive slope and the stock market returned +30.4% in calendar 1991.

On the flip side, the Fed surprised everybody a bit and began tightening monetary policy in February 1994. S&P 500 EPS were $21.89 in calendar 1993 and showed enormous growth to $30.60 per share in calendar 1994 and would even grow further to $33.96 in calendar 1995. Yet in the face of this wonderful increase in earnings, the S&P 500 returned only +1.3% in calendar 1994, and if you exclude the +3.4% return in January 1994 BEFORE the Fed started tightening, the Feb-Dec return was a negative -2.0%.

Feel free to disagree and short away at the market, but monetary liquidity rules, these days.

Anarchus,

Sorry, I just can’t post. I did not mean to hide behind Anonymous. I agree that monetary liquidity rules many things but it is not the greatest driver of the stock market. The 1970s are the best example. Massive injections of liquidity actually decreased real value in the stock market.

Dick:

No question, in the 1970s the excess surge in liquidity went into consumption and real assets, fueling a massive UNANTICIPATED inflation that pushed nominal interest rates to unheard of highs, turned the dollar to dross and ended up with the US issuing “Roosa Bonds” denominated in foreign currencies.

In what I’d call the modern financial era (US off the gold standard, Bretton Woods gone forever and most importantly the US money market mostly deregulated), real bond yields have tended to be higher and partly as a consequence, excess monetary liquidity has gone into financial assets rather than consumption and/or real assets. To some extent, we call inflation in financial assets a “bull market”.

Tony:

“Unless this anomaly can be explained, it is quite plausible that the US will, also, experience a soft landing.”

One big difference: the UK house building industry tops out at 150,000 new homes built per year (if they’re lucky). The US was building something like 1.2 million this past year, and selling about 120,000 new homes per month. The UK population is around 60 million, the US just under 300 million. So you guys have 5 times the population, but nearly 10 times the amount of new homes being built per year (when compared with the UK).

This is obviously not the only reason for why the US may not achieve the UK’s “soft landing”, but I think it’s one of them. Any thoughts?

just_observing,

The open, available land for housing is significantly different in the US from the UK.

Dick,

“The open, available land for housing is significantly different in the US from the UK.”

I know. That’s exactly why the US will not follow the UK’s example. US homebuilders can continue building, as they don’t face the same constraints as UK homebuilders, and increase supply even in the face of shrinking demand. Maybe I should have been clearer on that.

Anarchus

No question, in the 1970s the excess surge in liquidity went into consumption and real assets, fueling a massive UNANTICIPATED inflation that pushed nominal interest rates to unheard of highs, turned the dollar to dross and ended up with the US issuing “Roosa Bonds” denominated in foreign currencies.

Let’s not get the cart before the horse. It was the floating of the dollar and the resulting unrestrained increase in liquidity that caused inflation. The increase in prices, including real estate, did not cause inflation but were a result of inflation, the debasing of the currency.

http://newmarksdoor.typepad.com/mainblog/2006/10/a_lot_of_lousy_.html

A lot of lousy, depressing news lately. You have to look hard to find some upbeat stories. Fortunately, the Door is at your service: James Hamilton argues that the confusing economic numbers we’re seeing make sense if the markets believe

Well this best-case-scenario you paint is at least partly observable in our real-time housing market research.

We first noticed a housing demand uptick in the second half of July – tightly correlated with rates surprising downward trend. Blogged about it here:

http://www.altosresearch.com/blog/archives/146-NAR-Confirms-Home-Sales-Increased-in-August.html

thus far into October, we’re seeing seasonal strength as rates have stayed low. Except in pockets where huge piles of inventory are on the market, prices are holding steady.