The dream rebalancing scenario, in which adjustment of the world’s imbalances occurs without fiscal responsibility returning to America, relies upon “decoupling”.

A rejuvenated Europe, stripped of structural rigidities, and a resurgent Japan equipped with a newly reformed financial system, pick up growth, and begin running bigger trade deficits. The U.S. moves to a glide path of sustainable growth with shrinking trade deficits. I remember this scenario being outlined when I was in the Government –already over five years ago now. It’s similar to rosy scenarios of global rebalancing circulated these days.

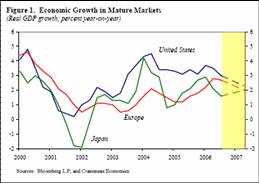

The newly released IMF “Financial Market Update” (December 2006) includes two interesting graphs. The first shows current forecasts for output in key regions.

Figure 1: Source: IMF “Financial Market Update” (December 2006).

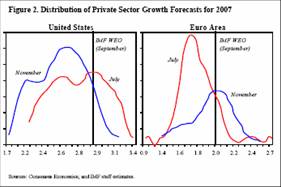

What is more interesting, in some respects, is the distribution of the forecasts. Figure 2 demonstrates that the bimodal 2007 US growth forecast distribution of July has transformed — and downshifted — to a unimodal distribution in November. In other words, the extreme optimists have been persuaded that growth is slowing. In Europe, the optimists are in ascendence, with the entire distribution of forecasts shifted upward.

Figure 2: Source: IMF “Financial Market Update” (December 2006).

So what are the prospects for an acceleration of growth? According Deutsche Bank’s World Outlook article “If the US sneezes, will the world still catch a cold?” (December 18):

- The risk of a faster pickup or slowdown in the US raises the question to what extent such surprises could spill over to the rest of the world. Recently diverging trends in US and foreign growth (and interest rates) have raised questions about a possible decoupling or drop in sensitivity of the rest of the world to what is happening in the US economy.

- A review of recent historical experience yields at best only mixed to weak support for the decoupling thesis. Indeed, rising shares of exports in GDP suggest coupling should be trending stronger. That said, periods of apparent decoupling can arise when divergent shocks to domestic demand are driving growth, as has been the case recently. The bottom line is that we still expect growth elsewhere to be noticeably affected by a significant change in

US growth prospects.

It might be useful to think about why high comovement is likely to occur. In the most basic Keynesian analysis, increases in aggregate demand get propagated via exports — i.e., the other country’s imports. In principal, movements in exchange rates, and other asset prices, can mitigate the direct Keynesian effects.

The authors (Peter Hooper and Torsten Slok) argue that decoupling can occur, depending upon the nature of the shocks; however, the fact that export intensity has been rising over time makes it less likely that decoupling can occur. While allowing the recent evidence of decoupling (namely the breakdown of the correlation between the Ifo index from the ISM purchasing managers index (PMI) in the past half year) is interesting, they point out that when the demand shocks go in the same direction (as DB predicts) then decoupling is more difficult. A VAR analysis indicates a one standard deviation shock to the PMI residual results in a 1.7 ppt reduction in the US PMI, and an eventual 5 ppt reduction in the EU-12 PMI-proxy after about a year. Other regions experience a smaller reduction.

To the extent that shocks to the PMI are demand shocks, decoupling might be difficult to accomplish.

Technorati Tags: decoupling,

exports,

trade deficit,

Europe

Such murderously good language Menzie (Grimm’s Fairy Tales have nothing on you who may have children that plead with you every night “No Dad, not another story!”).

For openers

And it gets better but, who am I to judge what is murderously good? Not little old murdered me…

But before I perish, (becoming absolutely decoupled from your prose maybe) I need to thank you for the illustration of fickleness of private sector forecasts and the mono/bimodal un/de/re/coupled/spill-over, somewhat less.

Menzie — hasn’t in some sense Europe already done the key bits “picked up growth” and started to run “bigger trade deficits”? True Europe trade deficit doesn’t seem to be expanding anymore/ isn’t comparable to the US deficit, but it is a lot bigger now than in say 04 …

I also am a bit curious why the emphasis is on “structural reform” in europe, rather than say other things that might contribute to a strengthening of domestic demand. structural reform — if that means a weakening of europe’s social safety net — could induce higher precautionary savings rather than a surge in business investment. that is at least one explanation for what has gone on in germany over the past few years. my sense is that the acceleration of demand growth in europe (notably in places like France and Spain) is more tightly linked to the housing boom than to structural reforms … some of the same forces that work in the US – surging capital inflows from emerging markets, rising home/ financial asset prices and the like seem to be having an impact on europe even in the absence of structural reform.

and for that matter, a pickup in oil state capital spending may matter more in the shortrun than structural reforms.

I don’t doubt that some kinds of structural reforms are needed in europe and would contribute to stronger growth over time. but in the short run doesn’t rebalancing mean sustaining demand? and aren’t policies that obviously support demand more important?

what worries me to be honest is that the roughly $100b swing in the eurozone trade balance since 04 — something that has come from acceleration in demand growth and overall growth — hasn’t done more to bring the US deficit down.

how about:

dems squeeze deficit spending much like repubs did to clinton and raise revenue with higher tax bracket (paygo). so fiscal resposibility can return to america.

I know that some investment banks are telling their clients the decoupling story. I agree with Menzie Chinn that decoupling is less likely in a more integrated world.

I think we should redefine what we mean by structural reforms. Van Ark had some papers showing that US growth outstripped EU growth becasue ICT using industries did so much better (Wal-Mart effect). In XXI century structural reforms are more likely to mean deepening ICT use, advancing e-economy, integrating country into global distribution networks, rather than fiscal, labor market and product market reforms. The latter ones are still very important, but without getting the former ones right, country is unlikely to increase its potential output. For me Singapore intelligent nation 2015 is an example of XXI century structural reform (link is below).

http://www.rybinski.eu/?p=166&language=en

brad setser: As always, an excellent question. In the short run, demand stimuli will be more important. But for a more durable increase in domestic consumption and hence imports, one needs some way of permanently lifting trend growth. That’s where structural reforms come in. And while I don’t think those will be a panacea for every ill afflicting the core EU-12, I think it wil be part of the solution.

Rybinski: As a staff member who worked on the 2001 Economic Report of the President, I meant the expansive definition of structural reform you mention. So in this sense, we’re in agreement.

From Dean Baker:

http://www.prospect.org/deanbaker/2006/12/most_important_economic_news_s.html#014769

“3) The Convergence of Employment Rates between the EU and the U.S. According to the OECD, the employment to population (EPOP) ratios for prime age workers (ages 25-54) in the EU 15 and the United States had nearly converged by 2006. The remaining gap is due to lower EPOPs for women among the countries of southern Europe, where cultural factors still work to keep women out of paid employment. Several European countries with strong welfare states, such as Ireland, Sweden, and Denmark, have higher EPOPs than the United States. This should be the end of the myth that welfare state protections lead to unemployment.”

Hum, structural reforms?