I earlier discussed the role that foreign government purchases of U.S. Treasury securities may have played in reducing long-term bond yields. A study by Fed researchers Glenn Rudebusch, Eric Swanson, and

Tao Wu that is soon to appear in

Monetary and Economic Studies explores an alternative explanation based on reduced volatility of underlying macroeconomic and financial fundamentals.

As Rudebusch, Swanson, and Wu note, the recent diverging trend between short-term and long-term yields has been fairly remarkable. In a typical episode of monetary tightening, as the Fed increases the fed funds rate, long-term yields also rise, though not as much. For example, between January 1994 and February 1995, a 3% increase in the fed funds rate was associated with a 1.7% increase in the 10-year Treasury yield. By contrast, when the Fed increased the funds rate from 1% in June 2004 to 4.25% in December 2005, the rate on 10-year Treasuries fell from 4.7% to 4.5%.

One explanation is that there has been a dramatic drop in the term premium, that is, a decline in the extra expected return that investors require in order to hold long-term securities. An objective summary of the risk that investors perceive from holding long-term bonds comes from the prices of option contracts on Treasury bonds. The lower the price investors are willing to pay for an option that only delivers if there is a big move in interest rates, the safer the long-term investment appears. The implied volatility from these option values (the Merill-Lynch MOVE index) has fallen quite dramatically since 2003, the same time that the yield curve has been flattening and now inverting.

|

To be sure, there have been other earlier episodes when long-term yields were similarly less volatile. Their study finds that such episodes often coincide with times when the long-term yield is lower relative to the short-term yield than you would have otherwise expected on the basis of standard term structure models.

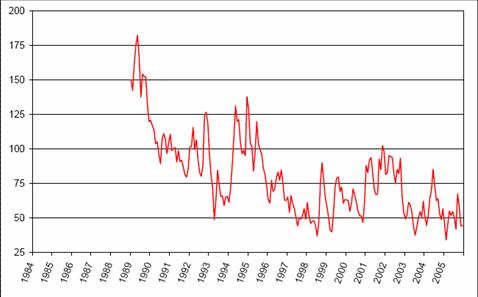

And what change in fundamentals could have warranted that re-evaluation of the risk? Margaret McConnell and Gabriel Perez-Quiros (another of my famous students, if I may brag), observed in an influential paper published in American Economic Review in 2000 that there has been a significant decline in the volatility of U.S. GDP since 1984. Rudebusch, Swanson and Wu note a further sharp drop between 2001 and 2005.

The graph below updates the Rudebusch-Swanson-Wu calculation of GDP volatility, and shows that this is climbing back up during 2006. To the extent that this accounts for the falling term premium, this anticipated increase in GDP volatility could lead to a steepening of the yield curve from its current inverted status.

|

Rudebusch, Swanson, and Wu also point to the fact that, Maria Bartiromo notwithstanding, the Fed has become far more predictable in recent years. One measure of this is a reduction in the implied volatility for very short-term securities:

|

Again, the easier it is to predict what the Fed is going to do, the safer long-term bonds become.

Rudebusch, Swanson, and Wu argue that these factors account for a measurable part– perhaps as much as 40 basis points, by their calculations– of the decline in long-term relative to short-term yields.

So perhaps there is another little chunk of that inverted yield curve that’s maybe not so scary.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

Federal Reserve,

interest rates,

yield curve,

term premium,

volatility

The decrease in the term premium brings up an interesting question. What if the reduction in volatility is a somewhat permanent feature due to better models and more accurate management of the money supply. After all, that seems to be the holy grail in the work of a lot of economists.

In addition there currently seems to be a reduction of the poorly understood equity risk premium. What if markets are more efficient than ever due to computers and the flow of electronic information such that investment risk is lower? Lower risk means lower returns.

If permanent, this would mean that simply saving money over a long period of time for retirement and expecting magical compound growth would be less effective. This would imply either working longer or harder while spending less and saving more.

News of the World #18

Lazy Thursdays… The Conspiracy Against Cuckolds, Robin Hanson on the dark and sexist side of “bioethics”. Highly recommended! Milton Friedman Days, from Cato-at-Liberty. Everyday should be M. Friedman day. Pot is called biggest cash c…

Joseph,

There are two sides to the equation. If returns decline because of the decrease in volatility then so do the costs.

Nice post.

I was thinking kind of the same thing Joseph. If the market lives on volatility and (it appears that) long term volatility is in decline, where does all the money go looking for the edge in return? In-and-out of Thailand? Some other place where the risk is ever greater, but the return not so great?

All of those nickles being scraped up in the derivatives markets could be turning to pennies because everybody is doing the same thing in the same way. If the result is me working longer and harder – then decreasing volatility would appear to have a rather perverse effect.

And how does drilling Thailand or some other hapless EM make this a less volatile world?

YOUR KIDS FUTURE

This is an editorial on the web site economy in crisis. Do you think Americans should be concerned with our kids future due to poorly negotiated trade and immigration policy?

PREPARE YOUR KIDS FOR THE FUTURE AS A SERVANT

EC-In 1994, more than 1 in 8 jobs in America was in manufacturing. In 2014, if US government (Bureau of Labor Statistics) projections are to be believed, that figure will have slipped to less than 1 in 12.

The government is actually telling us in black and white that the policies that they are enacting will decrease absolute and relative manufacturing employment to levels below that of the 1950s over 2 million jobs below. In the 1950s, 30% of US employees were in manufacturing almost one in three jobs! This country was a relative manufacturing superpower.

In less than 20 years since America put in place some of its most self-devastating policy decisions (NAFTA, WTO, CAFTA, etc.), this country will have almost completely converted from a self-sufficient sovereign state, capable of manufacturing what it needs to sustain and protect itself, to a country of servants serfs, working at the behest of foreign employers or engaged in the sales, marketing, and distribution of foreign-made goods working at their discretion, for wages they determine, and forced to pay their prices for needed goods. This is the definition of a servant.

I see JK has a one-size-fitzall post (please do some minor alterations/(connections to thread) John or I will show no mercy!), but I am left feeling that this:

is premature/blinkered/myopic…something that doesn’t need to be dressed up as 40bp worth.

Could be the consumption side of GDP does not last indefinitely and that the consumer sooner or later has to produce something other than a sales receipt for a new, bigger house.

I always gag when I see the line about decreased volatility in GDP and wonder what sophisticated accounting transgressions needed to transpire for that to happen in view of energy pricing. Of course there is that tricky Financial component that is always excellent at ensuring that low volatility GDP.

Such an un-Xmasy attitude to discard the fear about the coming slow-down, to resurrect Estrella and The Dismals…do enjoy the holiday nonetheless.

Re increased Fed transparency,the willingness of

the FOMC and the Fed desk to purchase Treasuries,

other than bills {remember Bill Martin)and maintain an adequate money supply,the Fed acknowledgement of its full employment mandate,

all of these developments which were not very

popular in the 50s,60s,70s and 80s,have contributed to observed decrease in GDP volatility

and the willingness of investors to accept less

than the historic real rate of return of 3% on

long term Treasuries.In all fairness,some recognition and credit should be acknowledged

for the persistent efforts of Rep.Wright Patman

to promote these objectives from the 1950s forward.Too often ridiculed as a “crank” Rep.Patman made a valuable contribution to the

evolution of how the Fed implements monetary

policy to-day.The writer served for many years

as an advisor to Mr.Patman.

Wilfred Lumer

Wilfred,

Your post has given me an opportunity to share a trend I see growing in our nation. More and more we seem to be interested in stability rather than in prosperity, or right and wrong. In our schools we are more interested in graduation rates than in education. We use tax policy to take from the productive and give to the less productive to balance incomes. The list could go on.

We have lost sight of how important imbalances can be. The whole idea of exchange, you getting what you want and me getting what I want involves inequality. If equality is forced on us, one of us and perhaps both of us will be unhappy.

That said, is a decrease in GDP volatility a good thing if an economy is prevented from producing at capacity? This does to some extent invoke the “broken window” fallacy in that, while we can see less volatility, we cannot see the lost production. I would rather see us reducing volatility in our measuring tools than in our production. This means that we should not look to remove volatility from GDP but to return to monetary stability.

Off-topic. James, did you see the New York Times article on the Interior Dept. study on oil exploration incentive programs? Comments?