Darn hard to talk about this without bringing in the speculators.

|

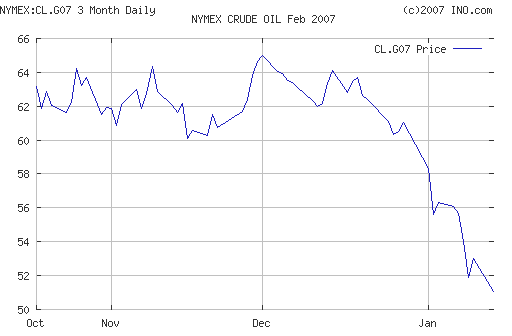

Let’s look at a couple of explanations for the recent plunge in oil prices that a priori might have been plausible, but don’t really seem to fit the facts. First, it’s natural to anticipate that the response of quantity demanded to the oil price increases over the last several years would take some time, as the fleet of existing cars, for example, gradually gives way to more fuel-efficient models when the older vehicles get scrapped. If demand declines have finally started to set in, that would be a powerful force in determining world oil prices. But even the most recent data continue to show U.S. gasoline demand still running pretty consistently higher than the previous year:

|

The rate of growth of Chinese oil demand has slowed, but the quantity of oil they are using is nonetheless still rising:

|

Another possibility is that the concerns raised here last summer about what the drop in Saudi production might signify about their intentions or abilities have recently been laid to rest. But Saudi production has fallen even more since then:

|

And how about a relaxation of geopolitical tensions? Tim Iacono slices that hypothesis to shreds with his customary wit:

Crude oil prices continue to fall amid cuts in Russian oil supplies, talk of cuts from OPEC, revolt in Nigeria, more nationalization in Venezuela, and a tinderbox in the Middle East.

What’s driving the price of oil down? It must be the weather.

Well, that and an apparent exodus of investors and speculators.

And I agree– the changed positions of speculators seem to be a big part of the story. The drop in U.S. inventories of crude oil has been pretty dramatic:

|

A change in crude oil inventories could signify a number of things. The traditional belief of many oil experts was that a drop in inventories meant that demand had unexpectedly exceeded supply, in which case the recent inventory plunge might be viewed as bullish for oil prices. But we have been out of that traditional regime for some time now. Instead, in recent years inventory accumulation has been an intentional response to the price incentives and investors’ perceptions about the future, and the dramatic decline in oil inventories must be read as a sign that that speculation is ending abruptly.

That drawdown in inventories– down 25 million barrels over the last five weeks– has meant 700,000 barrels a day in additional supply to the market just from U.S. inventories alone. That quantity of additional oil available for use can– and has– put a lot of downward pressure on prices.

The retreat of the bulls has not been limited to crude oil, but is also apparent in other commodities such as copper and zinc:

What could be driving all of this? An increase in the perceived probability of a global economic recession would fit the facts if we were just trying to explain commodity prices. But my reading of all the other indicators has been that this probability has decreased rather than increased over the last month. A drop in inflationary expectations would also explain the commodity price moves, if investors are just now figuring out that the Fed is not going to allow inflation to accelerate. But if anyone ever doubted Bernanke’s resolve about fighting inflation, I could have told them– and did— that they were wrong long ago.

What about attributing the run-up in oil prices almost to $80 a barrel, and now the latest drop back near $50, entirely to speculation, without any reference to fundamentals? The reason I’ve resisted that hypothesis is that it’s based on the premise that the folks who manage these funds are just throwing their money away. Buying high and selling low– which is exactly what is required if speculators alone sent oil up to $80 and now down to $50– is a good way to help your capital migrate to someone more deserving in a Darwinian sense.

In any case, it should be clear that any contribution from an inventory sell-off can only be temporary. After a few months of that game, you will run out of stuff to sell, and without that extra 700,000 barrels per day sloshing around, we’re back to the standard equation of how much oil is actually used to make engines go and keep houses warm relative to how much is coming out of the ground.

Until U.S. and Chinese oil demand are kept in check, and until big production increases are forthcoming, it’s hard for me to see how the price could continue to plunge.

My advice to would-be speculators remains that fundamentals are ultimately what must drive the market. Anyone who believes otherwise should not expect to hang onto their wealth for long.

Technorati Tags: oil,

oil prices,

Saudi Arabia,

commodity speculation

Such a refreshing run (review, examination, mullin it ova) through this more-than-portfolio interest, James. I do appreciate the apparent openness (see? I’m so guarded) and don’t know how you managed to not conclude that speculative interests were behind the rise and now the fall.

Do I have anything to disagree with other than the occurrence of “a priori” that ignites a whole barrage of barely quenchable outbursts? Not really.

It is a puzzle to me why China does not simply stockpile this commodity, which unlike tbills, is only going to get scarcer. Maybe their stockpiles are full? Is it possible that the large buyers are also the large speculators? [Blatantly showing my ignorance of the Futures market…the purity of my quest for knowledge is not proud.]

Is there not some coincidence between the change in trend in oil prices, the change in patterns of petroleum inventory management, and the hurricane season? If participants in the petroleum market are like the rest of us, sensitive to recent events in a way that is not entirely “rational” (in a homo economicus sense), then having seen what happened last year and having seen the standard forecasts for another busier than normal hurricane season, they would have built big inventories as a hedge against supply interruption. When the interruption didn’t take place, they found themselves holding more inventories than they need, and began to let them go.

This need not be the only factor, of course. There were commodity funds of various kinds being opened and marketed left and right. One type of fund that grew rapidly held (in a legal senses) actual physical commodities (this was mostly the case for precious metals, not oil), so had to accumulate inventories. China’s efforts to build strategic inventories (already doing what Calmo suggests they should do) was not entirely transparent, so when they ramped up purchases to build reserves and when (if) they subsequently went back a more normal pattern of purchase would not be well known. Speculators could be mistaken about Chinese behavior, as they were about the weather.

Seen this way, speculators were not intentionally buying high and selling low, which is the problem our host has with attributing too much of the recent swings in petroleum price to speculators. They were simply operating on the basis of bad information. They would not have been alone. Commercial users would have behaved in similar manner. Summer and autumn weather that was predicted to be bad turned out to be good. China didn’t (may not have) bought as much in recent periods as expected. More good weather in the late autumn and early winter amplified inventory problems.

In the long run, I’m perfectly happy with the notion that speculators aren’t stupid. What we are talking about here, though, is a sufficiently short period of time that an unusual concentration of stupidity cannot be ruled out.

I don’t think so, but close. The only ones who can spec with actual inventory are the commercials, who would have filled their tanks and sold the futures short, earning the contango. As the specs got short on the break (trend-followers, etc), the commecials bought back futures (from the specs) and used up the oil. Committment of traders bear this out, I think, as the specs have become shorter and the commercials longer on the break.

News of the World #19

A Four from two edition, with Marginal Revolutionaries and Econobrowsers. Marginal Revolution Did World War II end the Great Depression?, in continuation to the debate that seems to have died out, about FDR and the perverse effects of his “New De…

Many on Wall Street have attributed oil’s recent 15% of so fall to hedge funds (See SC Bernstein’s recent piece by Neil McMahon et. al). They note that the futures market is contango, especially in the outer years, because hedge funds have had to go farther and farther out on the curve maintain exposure and avoid negative roll. Without going into details, a contango curve begets more of a contago curve as speculators move farther and farther out on the curve to avoid the negative roll associated with an upward sloping futures curve. Bernstein argues that many hedgies will eventually give up as the roll game becomes too expensive and/or too illiquid farther out on the curve. They also don’t believe that oil will do well in the short term as the market adjusts to a flatter futures curve and speculators leaving the market.

Interested parties may also note the absolutely fanatastic performance by a listed stock-ICE-the leader in energy futures. The stock is enjoying great volumes and earnings and its pop in open interest supports the above thesis. It sounds like things may slowdown as hedgies leave. Perhaps a short?

JDH’s post reminds me that not only is a great economist, but a great teacher. One of the best I’ve ever had.

Tim, if your “I don’t think so, but close” was in reply to me, you may be taking what I said to literally. If not, ignore this.

There is no need for specs to hold physical product in order to take inventory needs into account. If there may be a shortage of oil, then holding the future could be profitable. Similarly, those without adequate storage, while vulnerable to supply interruption, can at least hedge the cost of lost business by holding futures. The EIA picture of inventories vs the 5-year band show inventories abnormally high from early in the year. As I recall, inventories were not abnormally high prior to Katrina, so there was a change in behavior after the supply (and inventory) shock last year. Inventories began to head back toward the 5-year band at the end of the hurricane seasion.

About 70% of energy consumption is buildings and 30% transportation. How much of that consumption is heating? Would warming drive winter consumption down more than summer driving drives it up? I don’t think so, but it is an interesting question. (I believe there is a biennial flow controlling hurricanes so we should see more this year.)

True, Tim, but the two are tied together by the mechanisms I described here, for which the appropriate executive summary is that it is the behavior of the financial speculators that ends up driving the physical inventory management. It is the speculators, not a commercial taking a covered inventory position, who absorbed the loss.

Another reason factor was Katrina and refiners. Cf http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/oog/info/twip/crpsusm.gif

Moreover, do we have any data that hedge funds increase volatility? Funds would appear natural volatility sellers by nature, either explicitly or by trading style, which would tend to cushion rather than amplify market moves. The NYMEX put out a white paper concluding as much a couple years back. For the PDF, viz http://www.nymex.com/media/hedgedoc.pdf

“My advice to would-be speculators remains that fundamentals are ultimately what must drive the market. Anyone who believes otherwise should not expect to hang onto their wealth for long.”

but if speculation itself drives the market – why would speculators need your long term advice ? speculators both create, and profit from, short term volatility, the overshoot that occurs in both directions. why assume that the speculators are losing out ? the suckers are losing out, while the smart money is busy shorting stuff and getting a repeat ride. the risk which is anathema to you – is a powerful attraction to others.

rightly or wrongly the speculators may be betting that iran will fold like the russians in the 1963 cuban missile crisis, and geopolitical risk go into decline.

Gilles, the average spot price while inventories were accumulating exceeds the average price at which they are now being sold, a transaction on which somebody definitely lost money. If, as I noted in my previous comment, the inventory transactions were covered with offsetting futures, that somebody was the speculators who bought the January futures contracts.

An earlier post here explains why it has to be that way. Speculation is ex-post destabilizing if and only if the speculators lose money, and it is stabilizing if and only if the speculators earn a profit.

To elaborate, by “destabilizing”, I mean that, in the absence of speculative buying of futures and the accumulation of inventories this induced in July, the July price would have been $70 rather than $80, and in the absence of selling off inventories now, the price would be $60 rather than $50. The only way to move from $70 to $80 is if speculators were on net buying at $80, and the only way to go from $60 to $50 is to have extra selling at $50. Hence, destabilizing speculation required buying high and selling low.

You can always pretend that the “really smart” guy was the one who bought at $75 and sold at $80. But it was a buyer, not a seller, who was responsible for getting the price up to $80. For every “really smart” speculator you come up with, I can point to even more who were “really dumb”, if the net effect of their actions was to cause the price to go all the way to $80. For that reason, any deviation from the fundamentals price path requires some serious suckers who were pitching their money away.

Why Are Oil Prices Falling?

Lynne Kiesling I have my ideas, but instead you should read this outstanding and clear post from Jim Hamilton at Econobrowser. He does a superb job of analyzing the macroeconomic factors that intersect with other commodity market drivers….

JDH,

It appears that your explanation is the only one left after eliminating all the others. I expect that the price of oil is returning to a more normal level. This would mean that it should not drop much below $50. If it continues to drop below $40 we could be in for some serious shortages as this would force marginal producers out of production and it is difficult to recover the lost of production.

JDH,

Nice analysis.

I’ve come to realize in the past year that one cannot really understand the behavior of global financial markets until one acknowledges that most market volume is now in the form of unbelievably-leveraged speculators. This goes beyond hedge funds: the big “investment banks” are now at least as much driven by speculative trading as by banking (Goldman-Sachs, for instance, got the majority of its revenue from trading as of the last report).

A lot of hedge funds (and maybe larger entities) are rumored to be set to go belly-up; half as a result of the machinations of their own brethren (the other half, of course, is from using too much leverage).

I think it was money bubble, just like housing, and the Fed burst it.

W$J

Same Crowd Behind Oil Rise Now Sells Out

Large Investors Got In, Find ‘Rollover’ Costs Too High to Stay On

By Ann Davis, January 9, 2007; Page C1:

Crude oil’s run last year to close to $80 a barrel drew cries that bullish investors were creating a commodity price bubble. Now it looks like some of the same investors could be accentuating crude’s downward slide. The appeal of holding oil as an investment has changed. Oil itself is losing value — crude-oil futures yesterday closed at $56.09, down 27% from a July 14 peak on the New York Mercantile Exchange, mainly as mild winter weather reduced heating demand.

Moreover, investors are finding it costs a significant amount of money to keep skin in the game in the oil futures markets during the decline. Unlike the stock market, even if crude goes nowhere in 2007, investors employing a buy-and-hold strategy will actually lose money because of the heavy costs of holding oil futures investments. …

Oil-futures contracts expire every month. Investors holding the most current contracts have to buy new ones to replace them if they want to maintain their positions. In the past couple of years — in part, because of the influx of financial investors making long-range bets — these contracts have gotten pricier the further into the future they are scheduled to be delivered, something known as contango. That raises the cost of keeping a position in the market. It’s almost like the difference between walking a mile, and walking a mile uphill.

About two years ago, spot prices of crude were higher than future months, something known as backwardation, which boosted investors’ returns every month. In practical terms, for most investors with oil in their portfolio, the cost of rolling over the expiring near-month futures contract into the one for the next month’s delivery is now more than $1.25 a barrel. The price of oil could be unchanged at $50 per barrel, and an investor would still lose 2.5% because of these costs. …

This is affecting large institutional investors, such as pension funds, which have been pouring into commodities in recent years, seeking to diversify their portfolios. A few years ago, they were happy to pay the “roll cost” to hold oil, because its price was rising and canceled out carrying costs in the futures markets. …

Meanwhile, another big question mark is hanging over the market: rising inventories.

… report published last month by Bernstein attempted to quantify just how full storage is in independent, commercially operated storage terminals that traders can use. The research firm’s answer as of December: 97% is full, up from 85% 18 months ago and around 70% in 2003. In pockets of the world where storage is especially full, supplies could flood the market and depress prices, Bernstein analysts contend.

A different set of financial speculators — including hedge funds and trading firms that buy and sell physical barrels of oil — have been investing heavily in crude inventories because of the futures market phenomenon.

These speculators enter a contract to sell oil months or years into the future. Then they fill their tanks with oil that they buy more cheaply on the open market. The difference between oil delivered next month and that for August delivery, for example, is roughly $5 a barrel. These speculators pay a few dollars for storage, but still pocket a few dollars a barrel in profit. Some economists think this strategy could unravel should storage facilities fill up. …

Jan. 17 (Bloomberg) — More than 90 percent of the London Metal Exchange’s aluminum stockpiles are held by a single group, LME data show.

The warrant holdings report also show more than 90 percent of lead and zinc stockpiles being held by one group of investors.

On June 28, 2006 the SEC ruled that BP traders illegally cornered the U.S. propane market, creating price spikes that affected some seven million households.[1]

In business, cornering the market is an illegal attempt to buy up enough of a particular commodity to allow the price to be manipulated. It is also possible to make even more money by buying futures contracts on the commodity, and selling them at a profit after inflating the price.

This is easily one of the best blogs on economics. The analysis and views are fresh and enlightening. Thank you Sir, this blog has been of great help. Mostly people have been citing warmer weather and less speculation as the reasons for the oil price fall (Economist also gives a very good analysis of the same http://www.economist.com/finance/displaystory.cfm?story_id=8523694 ). But to look at inventories is one other dimension not reported so far.

Opening Bell: 1.18.07

Apple’s Forecast Falls Short After Record Profit (Bloomberg) Steve Jobs? Can him. Obviously, it was easy to defend Steve Jobs when the turtleneck was made of teflon, and Apple never had a slip up. But the company warned that its…

Does Amaranth (yeah, I know, different market, but close enough) count as a dumb speculator?

How many petroleum Amaranths are out there, waiting to fold?

I left out a piece of the puzzle. The contango was driven not by traditional speculators, but by index investors (GSCI, etc). The break in crude has been very profitable for traditional specs, bad for the indexes.

“But it was a buyer, not a seller, who was responsible for getting the price up to $80”

JDH – thankyou for taking the trouble to explain your take on speculation. i suspect that we are not in fundamental disagreement, but only differ on how to express in words what is happening.

perhaps i am being slightly pedantic, but i have to say that every trade at $80 required both a buyer and a seller at that point. i understand that speculators can be stabilising when they act modestly by buying what nobody wants and selling when shortages drive up prices. my own practical experience is in cattle markets. the scene is different. the principles are the same.

i also understand that speculators are destabilising when they act with the markets – buying into booms and selling into panics.

but there is a modern phenomenon where markets exist in which the speculative trades far exceed the ‘genuine’ trades. there is an underlying ‘genuine’ market price, but who the hell knows what it is ? by this stage it is like a small hill underwater, made irrelevant by a flowing, or an ebbing tide far above its head. the speculators now not only buy into the boom, but create it. it now becomes, as you understand well, a market in which the average speculator will lose out.

so what ? these guys are not backing horses with the housekeeping money, they are gambling with the profits of gambling. it is play money. some are gambling with other peoples’ money and in it only for the percentage, win or lose.

go and tell the guys at the race track that the average punter loses. they will say ‘get lost’. they want to be one of the minority who win, and win bigtime.

i suspect that there is some symmetry in overshoots and overselling. if the oil price hits $80, as you suggest perhaps $10 over the price that might obtain in the absence of speculation, then it is likely to hit $50, which you similarly suggest is $10 under such a price. if the oil had gone to $100 last year, it could equally be headed for say $25 this year or next at the bottom of the sell off. so who ensures that oil will head for $40 which it easily might ? the same fellow who bought it at $75 and rising, and helped create the spike.

Gilles, yes, at the time oil sold for $80, the number of buyers of the contract exactly equalled the number of sellers. But, at that instant, if the price had instead been $75, the number of buyers would have exceeded the number of sellers. That’s the sense in which I say it was buyers, not sellers, who drove the price to $80.

A lot of the crude and product distribution and storage assets which used to be owned and operated by oil companies have gradually been sold and consolidated and are now operated as fungible systems by 3rd parties – the Kinder Morgans, etc. There are a lot of advantages to that, overall. But I wonder if we are seeing the futures market interacting with the physical market more because its easier for the financial industry to get access to the storage facilites…

“That’s the sense in which I say it was buyers, not sellers, who drove the price to $80.”

no sir. the buyers wanted the oil for $75, the sellers hoped for $85, and it was the interplay of the two in the market which struck the day’s (or moment’s) balance at $80. in any deal it is the seller who talks the price up, and the buyer who talks it down. the sellers got the price up to $80 because of plentiful speculative buyers.

a deal is a deal. you cannot hold either side alone responsible ?

“I think it was money bubble, just like housing, and the Fed burst it.”

Yeah except housing prices haven’t fallen like oil prices.

If the housing market does fall 35% just as fast as oil did, everyone will say surely say “the housing bubble finally burst”. And when the stock market did fall as fast as oil just did, everyone did say “the stock market bubble finally burst”.

So maybe it’s just that the oil price bubble finally burst?

(And the “end of oil” isn’t nearly so near as it appeared to some at the height of the bubble?)

Jim: House prices do not move like commodities contracts. Commodities contracts expire every month. Houses not sold are still lived in. Oil incurs warehousing charges.

Today’s W$J:

Mild winter weather has something to do with it. So does heavy selling by financial funds. But a largely overlooked factor in the recent plunge in oil prices may portend an end to the multiyear rise in crude: For the first time in years, the developed world is burning less of it.

Fresh data from the International Energy Agency show oil consumption in the 30 member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development fell 0.6% in 2006. Though the decline appears small, it marks the first annual drop in more than 20 years among the OECD countries, which drain close to 60% of the 84.4 million barrels of oil used globally each day. Industrialized nations’ demand tiptoed into negative territory in 2002, but the dip was so slight that it registered as flat.

Yesterday, U.S. benchmark oil for February delivery settled at $50.48 a barrel, down $1.76, or 3.4%, on the New York Mercantile Exchange. Earlier in the day, futures fell below $50 a barrel for the first time since May 2005, hitting a fresh 20-month low after the Energy Department said U.S. crude-oil stockpiles rose the most in more than four years. Oil has been sliding since peaking above $77 in July. This year, prices have fallen 17%.

The tipping point where oil prices begin to erode demand was reached last summer, several industry analysts said.

Jim Glass

It’s widely understood that housing prices are ‘sticky’.

When the market is bad, sellers won’t take the prices offered, and buyers won’t pay them.

A housing market ‘crash’ is therefore much more about falling volumes of sales, than about falling prices.

At least in the first couple of years. After that, prices may start to equilibrate. Because of job changes, divorce, etc. sellers have to sell, eventually, and they take down their prices to do so.

But the deflating of a housing bubble can be a long slow and unpleasant thing. I’ve live through 4, and none was pleasant. Each had a 40% drop in prices, with the bottom 5 years after the top.

An example from the commercial real estate market. A colleague had his inheritance invested in an office building development in Calgary, during the 1980-81 oil boom.

In 1994, that building *was still unlet*.

Possibly (probably) Saudi Arabia has something to do with the drop. According to the NY Times:

“A member of the Saudi royal family with knowledge of the discussions between Mr. Cheney and King Abdullah said the king had presented Mr. Cheney with a plan to raise oil production to force down the price, in hopes of causing economic turmoil for Iran without becoming directly involved in a confrontation.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/22/world/middleeast/22saudi.html?pagewanted=2&ei=5090&en=1f751353ba56eaa7&ex=1324443600&partner=rssuserland&emc=rss

What can drive the oil price down?

If there is an annoucement and a verification of a technology that can supply 1/2 of the world energy need, green and renewable.

I think the technology is there.

If you and/or your scientist can check out at:

http://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=wind+turbine+wave&search=Search

Happy to us all.

PTR