Why do Americans love their ethanol so much?

Growth of ethanol as a fuel source in the United States has resulted from tremendous subsidies at the federal, state, and local level. The biggest single item is the Volumetric Ethanol Excise Tax Credit, which grants a tax credit to blenders who combine ethanol with gasoline, in the amount of 51 cents per gallon of pure ethanol blended. But this is only part of the story, as detailed in a report released last October (hat tip: Cato Institute) by the International Institute for Sustainable Development. In addition to the direct subsidy from the VEETC, many states reduce motor fuel taxes on favored fuels, and there are numerous separate subsidies and tax breaks for investment in the infrastructure required for biofuel production. There is also a large implicit subsidy in the form of the mandate from the Energy Policy Act of 2005 that 4 billion gallons come from renewable fuels in 2006, rising to 7.5 billion in 2012. The impact of these mandates on the price of ethanol is greatly amplified by the 54-cents-per-gallon tariff currently in effect for imports of ethyl alcohol intended for use as a fuel. Finally, there are significant direct agricultural subsidies for farmers that reduce their water, fuel, and other costs below market. The IISD estimated that such subsidies currently sum to $1.05 to $1.38 per gallon of ethanol.

What this means is that the economic value of the resources that are used to produce a gallon of ethanol are nearly 50% greater than the value of the product to the consumers. Some have argued that ethanol is actually a net energy loss, requiring more energy in the various inputs than is contained in the final product, though the U.S. Department of Energy and a National Academy of Sciences study have endorsed the claim that there is some modest energy gain. But even assuming that ethanol does effectively add slightly to our net energy supplies, what sense does it make to pay attention only to the inputs of energy that are required in order to produce ethanol from corn, acting as if the inputs of land, labor, and capital can be valued at zero?

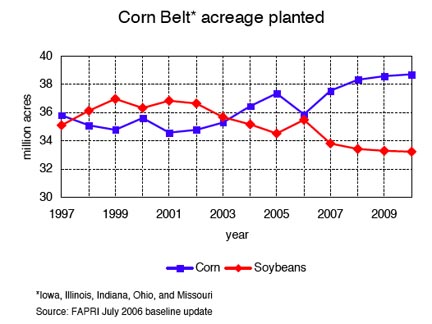

With 14% of the 2005 corn crop already going to ethanol production, devoting even more of the crop to making ethanol means higher prices for corn-dependent products ranging from soft drinks to bacon. The price of tortillas in Mexico rose 14% last year, a significant hardship for those who depend on corn as their dietary staple. Not to mention the fact that increased corn production also comes at the expense of other crops:

|

The NAS study claimed that even if 100% of the U.S. corn crop were devoted to ethanol production (leaving zero for exports, corn flakes, or whatever), it would only displace 12% of our gasoline consumption; (thanks again to Jerry Taylor for steering me to that estimate).

Although powering our cars with corn is vastly more expensive than other alternatives, this choice seems to be tremendously popular with most Americans. If an economist were asked to justify this attitude, the argument would have to be that the market cost of imported oil vastly understates its true cost to us in terms of geopolitical implications of U.S. dependence on foreign oil. But if that is the underlying rationale, the preferred economic solution would not be a subsidy to corn producers, but rather a tax on oil imports.

The subsidies and economic inefficiencies they create result in taxpayers and consumers paying more than they would under a simple, direct import tariff. A tariff would also produce strong incentives not just for ethanol production but also a variety of alternative energy sources and conservation, with the big advantage that market forces would guide us to the most efficient options on the table. But I guess the ethanol subsidies have the advantage that Americans can pretend that somebody else is footing this bill.

Technorati Tags: ethanol,

ethanol subsidies,

oil imports,

energy independence

A couple of other factors. First, Iowa, whose voters are crucial during the US presidential primary season, produces a lot of corn, so any candidate who talked about cutting corn subsidies such as the ethanol tax credits would probably not get very close to the White House.

Second, Archer Daniels Midland, a Midwest corn giant, does very nicely out of corn subsidies and is extremely well-connected politically.

Alexander,

Important points. Ethanol is more a political issue than scientific or economic.

Also thank you for the mention of ADM. Much has been made of the union of some big business with environmentalists on this issue and on global warming. I am surprised that anyone is surprised. Big business is in the business of maintaining and increasing their market share, so they will do almost anything to prevent competing interests from entering the market or having government mandate the use of their product. I am amazed at how gullible environmentalists and right wing Republicans are at the subterfuge of big business. Democrats are not as gullible; they are better at extortion.

Drawing in part on something Michael Mussa wrote years ago about the sugar quotas and in part on something Paul Krugman recently said, my Angrybear post a while back proposed we go for a sugar version as opposed to a corn version and just drop these trade barriers altogether.

“Why do Americans love their ethanol so much?”

Because, when properly mixed with Vermouth, it makes great martinis.

I think the ethanol craze is essentially a form of psychological denial, operating at the societal scale. People don’t want to change. For example, they don’t want to change the kind of cars they buy. They are going to have to, but they haven’t accepted this yet (at least not on the necessary scale). Politicians don’t want to commit political suicide by telling people they need to change (at least not before it’s blindingly obvious to everyone). The plan to massively ramp up ethanol allows folks to pretend that consumers don’t have to do anything different, but we can still address the vulnerabililities that our dependence on foreign oil imply. It’s an illusion, for all the reasons you mention, but I think broad recognition of this will only come after higher grocery store bills start to anger the average consumer.

I’m reminded of Churchill’s quote that “Americans can always be counted on to do the right thing…after they have exhausted all other possibilities.” Ethanol is a possibility we just haven’t exhausted yet.

Mexico’s Oil-Tortilla Paradox

Watch this brief video on the politics of ethanol and try to find the highly relevant, but omitted, fact that renders the narrator’s entire thesis invalid:

Thanks for taking on this issue. Some people think I’m nutts when I tell them corn-based ethanol is bad. Being able to direct them to things like this rather than my rantings about replacing dependence on foreign-oil with a dependence on foreign-water (e.g. draining the Ogalala Aquifer to grow corn) is all we’re doing.

Does anyone know the energy content of 85% methanol?

Does the tax credit just offset other taxes on ethanol? After all, liquor taxes are quite high. Corn is increasing in Mexico due to a reduction in subsidies. It is difficult to know what is a tax and what a subsidy these days. The one thing ethanol has going for it is security of supply, and that may even be worth the price, high though it may be.

I hope Prof. Chinn doesn’t see Prof. Hamilton’s post; I assume that there’s worship of corn stalks and ethanol stills on the Madison campus, and I don’t want to see a spat between them break out.

Gosh, with all of this objective analysis about alternative energy and its true cost, who knows, we may even see positive things about nuclear power on this site in the future.

Keep up the good work, sir.

Herr James, Ethanol is the key for curbing global warming. All that steam will cool the earth hark.

Thank you James for this bit

What non-third world country on this planet does not put a tax on oil imports?

And here too:

and the vastly understated geopolitical reasons why we have aircraft carriers to park at foreign doorsteps if they think we should adjust our American lifestyle and drive something smaller than GM’s Brontosaurus.

Suprised that the professor accepts so quickly the common claims (repeated over and over in the MSM) about Mexican tortillas. Certainly subsidies (and their changes), droughts, and NAFTA and tariffs figure into Mexican prices quite a bit.

Regarding taxing imported oil – how elastic is oil demand? Won’t the end result be only a slight decrease in oil use but a large increase in goverment revenues? (Perhaps economists might think that is a good thing…..)

pgl,

Are you saying there is no sugar subsidy?

Another problem with ethanol is that most of the energy inputs are in the form of natural gas, both as a feedstock for fertilizer manufacture and also to heat the boilers used to distill the ethanol. NG unfortunately is coming into short supply in North America and efforts to increase imports of liquified natural gas have not been too successful.

Hal makes a good point about natural gas. In particular, one of the effects of natural gas price increases (and volatility) has been a shutdown of a sizeable fraction of the US fertilizer industry. Statistics from here suggest fertilizer imports have gone from $2.45b annually in 2000 to $6.1b in 2005.

So much for ethanol reducing our strategic vulnerability. (This year, fertilizer manufacturors are probably having a better time because natural gas prices have moderated for the moment, and the price of fertilizer has gone up sharply due to ethanol related demand for corn (which requires 30 times as much nitrogen as soybeans).

Maybe a good chunk of the answer is fairly simple. One of the factors that drives the ridiculous over-success of the farm lobby in both the US and the EU seems to be a sort of pervasive primitivist back-to-the land romanticism. The sort of thing that is often found in peak-oil writing. The sort of thing that in part drives much of the environmental movement. It’s that safe-as-long-as-nobody-implements-it hankering for the dead past when the world was not contaminated by the (moral) impurity of cities, the dead past when life was “simple” and thus imagined to be politically-correctly “fair” to the shiftless.

The people who lived (or still live) in that sort of misery knew/know better, but real world information never stopped romantics in the past and certainly won’t now. That’s my two cents anyhow.

Another problem with ethanol is that most of the energy inputs are in the form of natural gas, both as a feedstock for fertilizer manufacture and also to heat the boilers used to distill the ethanol.

Actually that is part true… the NG to fertilizer part. Most of the really large ethanol plants (Cargill & ADM) now use co-gen processes and burn coal instead of NG. And plants are getting bigger all the time.

Think of a large corn wet mill as a coal synfuels fuels plant that inputs corn and coal and outputs ethanol, electricity and corn by-products… not unlike a ‘regular’ synfuels plant that inputs coal and outputs electricity and gasoline.

Of course from a greenhouse gas perspective burning coal is even worse than burning natural gas. One more knock against corn ethanol.

BTW – my first job out of college was as a plant floor processes engineer / supervisor in what was then (and still is) the largest ethanol plant in Iowa. I saw the sausage being made.

I firmly believe biofuels have a prominent future but corn ethanol is NOT one of them. It will always be ‘marginal’.

I look for biomass gasification using Fischer-Tropesch chemistry to produce liquid fuels as being more promising… with feedstocks like elephant grass, poplar trees, hemp, and switch grass as more likely than anything we would actually eat. Look for crops that (1) have HUGE ton/acre yields and (2) grow about anywhere with little input and (3) harvest easily & with minimal energy input to harvest & transport.

Fermenting cellulostic feedstocks like the ones I mentioned to make ethanol is possible but FAR more challenging than people understand. I studied the process on my way to my BS Chem Eng degree 25 years ago… and there hasn’t been a lot of solid progress since then… the cellulostic ‘beta acetal’ bond is a bitch for enzymes to crack at high rates (versus the much easier ‘alpha’ bond in starches – the usual fuels for fermentation processes).

Which is why potatoes rot FAST and trees don’t. And also why corn is easy to ferment and grass stalks or wood chips aren’t.

and the price of fertilizer has gone up sharply due to ethanol related demand for corn (which requires 30 times as much nitrogen as soybeans).

But not 30 times more fertilizer needs to be added going from beans to corn. There is considerable natural fertilizer even in commercial production plots… natural nitrogen fixation… So planting corn requires more than beans (which fixes its own) but not 30 times more has to be added.

HOWEVER – going from a bean-corn-bean rotation to a perpetual corn-corn-corn ‘rotation’… if it can be called that… requires 50% more fertilizer. I got that from listening to the Iowa State University public radio station while driving through Iowa recently.

Plus there is the concern that a static perpetual mono-culture will increase pest problems – and more chemical input requirements. No-till increases that risk even more (provides refuge for pests to ‘carry over’ in.

There is no free lunch.

Dryfly:

My source is this Bloomberg piece, which says “Corn requires 30 times more nitrogen fertilizer than soybeans, the crop it often displaces, Merrill Lynch & Co. analyst Don Carson said. Nitrogen prices in key markets are the highest in 25 years in anticipation of extraordinary spring demand, he said in a Jan. 18 report. Rising ethanol production could keep corn and fertilizer prices higher than normal for several years, Carson said”.

I didn’t independently verify the number.

In looking back for that, I also stumbled upon this other Bloomberg piece from last August. It says:

The world may soon pay more than ever for its most abundant food: rice.

Maybe Lester Brown is about to be right at last…

What about a simple carbon tax at the pump? Import tax would be messy and could drive towards faster depletion of domestic reserves and cancel any effect of the doubling of the strategic reserve.

Sobre a traição do governo

Como se sabe, embora pouco divulgado, o governo atual foi cooptado e agora é aliado do temível e maligno governo dos EUA, cujos objetivos de dominar o mundo, claro, passam pela conquista dos pobres e inocentes brasileiros. Mas como isto…

One other thing that increasing the amount of corn that will be diverted into ethanol will do in the longer term is increase the acerage of crops that are grown. As prices rise they will become attractive. Where does the water to grow these crops come from? How much is abstracted from boreholes and who has the first rights over that water, people or farmers…you’re in for a couple of interesting years….

More on Ethanol tariffs and subsidies

There’s a pretty solid piece on the economics of US tariffs subsidies and the costs of US ethanol production over on Econobrowser. (In my experience economists are much more interesting than accountants… must be something to do with scale and…

If the goal is to reduce our usage of oil, increasing the fuel tax would be the best way to reach that goal. Unfortunately increasing the tax is politically unsavory, and any resulting reduction in demand would take time, as demand for gasoline is extremely inelastic. The tax would have to be high enough to drive demand away from gasoline, but not too high as to cause widespread protests. The tax would also work best if the amount varied for each area, but getting that idea past the public would be tougher than raising the gas tax itself. The issue is political, not economic, which is why political goals may be reached (i.e. a happy farm lobby), but economic ones will not.

What about a simple carbon tax at the pump?

HZ,

How does taking money from producers and giving it to government produce more energy products? Certainly you can reduce usage but at the same time you reduce productive efficiency. Why do you want to do that?

An interesting story in the NYT about inflation in India, and rising food prices in particular.

Not that HZ can’t answer you DickF, but this “reduction in productive efficiency” as you put it, caused by a tax at the pump, preempts the oil industry’s future price hikes and creates a fund that can fuel alternative and conservation approaches…like the civilized parts of the world where cars are less than half the size and gas 2 or 3 times the cost.

It is the most glaring feature of our Energy Policy: it is run by and for the oil industry.

Stuart Staniford:

Interestingly, the NYT article includes a graph which shows India’s price index growing at 7-9%, while Chinese consumer prices are flat despite the yuan nominal peg.

DickF – big businesses are run by *people*. People like Lord Brown of BP and Lord Oxburgh of Shell, who are trained scientists and engineers. Their intelligence tells them global warming is a real problem, with real long term consequences.

The Managing Director of Marks and Spencer had his whole board watch ‘An Inconvenient Truth’. M&S, a retailer of clothing and food, hardly has anything to gain from more government regulation around global warming. Yet Stuart Rose is worried.

The alliance between environmentalists and some of the world’s leading corporations is hardly false. It’s common interests.

You are right about (some) Republicans and big business. But then the majority of the Republican infrastructure of think tanks, meeting groups etc. is funded by a section of right wing businessmen. Think Haliburton, SAIC and Blackwater and the profits from the Iraq contracts which the Comptroller General is now investigating. This has been well documented. He who pays the piper, calls the tune.

Valuethinker,

If your take on paying the piper is true it should give you pause when big business jumps on the Global Warming issue.

China is making big bucks from selling CO2 credits. Many of these producers see that they can benefit from such credits and at the same time lock out competition. They also see that in the US there is a Democrat congress that is taking direct aim at oil companies so they want the Republican president to take action to stem the tide.

I am not sure you realize it but central planners are the ones who hand out money to big business. A free market would give everyone a chance to compete and big business would actually have to invest in production rather than lobbyists.

…a tax at the pump, preempts the oil industry’s future price hikes and creates a fund that can fuel alternative and conservation approaches…

Calmo,

Price hikes in oil are due to restrictions exploitation of known fields and on exploration additional exploration to increase supply, inflation, government regulations and mandates of gasoline mixtures and additives, and other such intervention in the market. The oil companies love this kind of intervention because it locks out competition and forces up the cost of their product so that with the same ROI they can generate more revenue.

Concerning the government funding alternative fuel research first the government takes its cut of such taxes. If the result is as good as welfare about $.25 of every dollar ever gets to the intended purpose. Then this $.25 is distributed to alternative energy research that will buy the most votes such as the topic we are discussing ethanol production, not to energy research that is actually most cost effective.

You have to understand that central planning will always waste resources and then invest whatever capital is left in yesterday’s research. If you question this ask any Russian who lived under the USSR regime.

Thirty times –

Generally no synthetic nitrogen fertilizer is used in the production of soy beans, they net add nitrogen to the soil.

On the other hand – corn likes about as much as you can afford.

Now back to the calculation what is 30 times minus anything. I am certain that thirty times isn’t the right answer.

Bill

Generally no synthetic nitrogen fertilizer is used in the production of soy beans, they net add nitrogen to the soil.

Not sure that is accurate either – yes legumes fix nitrogen BUT there are more nutrients than nitrogen. And even nitrogen might be needed depending on the previous crop rotation & soil condition…

Read Here…

I definitely believe that the subsidies for ethanol should be eliminated.

However, the relationship between ethanol production and the price of tortillas in Mexico is somewhat more complicated than the post and the discussion above might lead one to believe. Yellow corn is used to produce ethanol in the United States; white corn is used to produce tortillas in Mexico.

Mexico doesn’t import a great deal of white corn from the United States and what it does import has been dwindling over the last ten years or so. The reason for this has less to do with rising prices of white corn as a consequence of ethanol production than it does to Mexican agricultural subsidies.

I haven’t seen any evidence that resources in the U. S. are being transferred from the production of white corn to the production of yellow corn for use in making ethanol.

So, why are tortilla prices rising in Mexico?

I haven’t studied the matter in depth but I can offer a few guesses. Mexico is no longer a poor country by World Bank standards—it’s a middle income country with a lot of poor people in it (like China and India). Given Mexico’s rising wealth it would make sense that Mexico is producing more yellow corn (for use in animal feed) at the expense of white corn. I also suspect that the subsidies for white corn production haven’t kept up with the general rate of inflation and, consequently, prices have risen.

Rather than this being a case of a bad guy (U. S. energy and agricultural policy) and a good guy (Mexico) I think this is a case of no bad guys or good guys but lots of bad policy decisions all around.

Dave, I’d be very surprised if there is not strong arbitrage between the price of white corn and yellow corn, as between the price of corn in the U.S. and Mexico. Looking at the quantity of imports or exports often has little relation to the question of whether there is arbitrage between prices.

DickF

Global Warming is the largest negative externality we’ve ever created (excepting perhaps nuclear war).

You can’t stop an externality without some central force (call it the market, call it government) imposing a tax on the creation of that externality (the Coase Theorem).

In fact, following from Coase, we could grant the generations of the future the right to sue existing corporations for the global warming they have caused, and settle it in the Courts. It’s not likely to be a more efficient solution than what is proposed.

I’m always fascinated why Libertarians of all people seem so het up to deny global climate science. It’s like it offends something primal in them, this notion that human action can change the planet we live on.

Valuethinker,

The accepted wisdom is that we must do something about Anthropogenic Global Warming because the issue itself is so critical whether the the science demands it or not.

First point with a question:

We know that historically there are periods in history when average temperatures were 1-2 degrees higher or lower than they are today. Can you name any period where an average temperature 1-2 degrees higher created a climatic disaster?

Second point:

In periods where the average temperature was lower there have been significant climate concerns. One obvious period is the Little Ice Age. If you look at the high and low points of civilization compared to average temperatures you will see that declines in civilization match with declines in average temperature while advances in civilization match with increasing temperature.

Point 3:

Assume that we do nothing and AGW is true. The historical record suggests the result would be a boom in civilization or in a worst case nothing would happen. Now assume that we are successful in lowering the average temperature by 1-2 degrees and AGW is not true. We could create a climate disaster to rival the Little Ice Age.

Most people have not thought through the problem because it has become a political rather than a scientific issue. Taking action against AGW has the potential of being much more dangerous for the environment than doing nothing whether AGW is true or not.