As I discussed in earlier posts, China retains some policy autonomy by virtue of the presence of capital controls. A recent working paper by Ma and McCauley attempts to quantify how binding the controls are.

From the paper’s Introduction:

Divergent interpretations of the interaction of monetary and foreign exchange policies in

China often arise from different assumptions regarding the efficacy of capital controls. At one

extreme is the view that capital controls merely change the form of capital flows without

altering their magnitude. On this interpretation, pegging the exchange rate or closely

managing its path implies that China imports its monetary policy and lacks control over

domestic short-term interest rates. At the other extreme is the view that capital controls are

still effective or binding enough to allow short-term interest rates to be set domestically, even

though the exchange rate is managed. The contrasts between these views sharpen in the

context of growing cross-border flows under both the current and capital accounts over the

past 10 years.

Different views on the status quo also inform the interpretation of the likely results of further

liberalisation of capital flows. Again, at one extreme, this would just unevenly lower

transactions costs and thereby alter the mix of cross-border capital flows, but without

necessarily affecting their total volume. On this interpretation, capital account liberalisation

might be of interest to specialists in international finance, but not to those who follow the

Chinese macroeconomy. At the other extreme, capital account liberalisation would influence

both the scale and composition of capital flows and ultimately force a choice between

exchange rate management and an independent monetary policy.

This paper examines both price and flow evidence to determine how effective China’s capital

controls have been in the past and remain at present. We put the analysis of prices first

because it provides the most telling evidence on the question. Our basic conclusion is that

sustained interest rate differentials argue that Chinese capital controls have continued to

bind, despite the responsiveness of cross-border flows to price signals in an increasingly

open economy. These observed differentials cannot in our view be plausibly accounted for

by liquidity or credit factors. Even the narrowing of these differentials since the unpegging of

the renminbi in July 2005 leaves them at substantial levels. If capital controls still bite, future

liberalisation is likely to proceed incrementally in order to accommodate a shifting balance of

exchange-rate, and financial- and monetary-stability objectives.

In this paper, we define monetary autonomy narrowly in terms of the government’s ability to

set short-term domestic interest rates. Such a definition may be appropriate to many

industrial countries where monetary policy has confined itself to setting a short-term interest

rate. In fact, China’s monetary policy employs a wide variety of other instruments, including

setting administered deposit and minimum lending rates as well as quantitative measures

like reserve requirements, lending quotas, window guidance and administrative restrictions

on investment. Such measures could give China’s monetary policy room for manoeuvre even

if its short-term interest rates were tightly constrained by the exchange rate policy. Thus, a

finding that short-term interest rates are not tightly constrained implies a fortiori monetary

independence in the broader sense that is more relevant in the case of China.

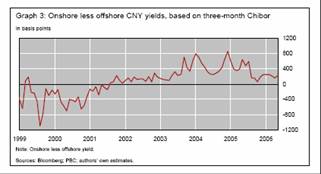

Focusing on the differential between onshore and offshore yields, they can identify the impact of the capital controls in price terms (see Cheung et al. for more discussion).

Chart 3 from Ma and McCauley, “Do China’s capital controls still bind? Implications for monetary

autonomy and capital liberalisation,” BIS Working Paper No. 233, August 2007.

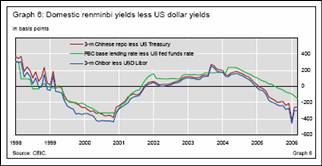

The fact that capital controls are somewhat effective means that PBoC can retain some monetary autonomy, as illustrated by the deviations in interest rates — even during the fixed rate period (pre-July 2005).

Chart 6 from Ma and McCauley, “Do China’s capital controls still bind? Implications for monetary

autonomy and capital liberalisation,” BIS Working Paper No. 233, August 2007.

Technorati Tags: China,

renminbi,

exchange rate,

yuan, and

capital controls.

There is a finance professor at Peking University who also read the BIS piece but is more skeptical of its findings. He claims, I think (see piaohaoreport.sampasite.com), that the interest rates the authors use are not a good proxy for monetary autonomy.

One is always on pretty solid ground to be skeptical of results involving Chinese data. That being said,in Cheung et al. (2005), we note the difficulties in identifying an interest rate to use. But in the end, one has to do the best one can; for now the interbank rate seems as good as any other. In our various papers, we have used different series, to see if the results differ as a consequence.