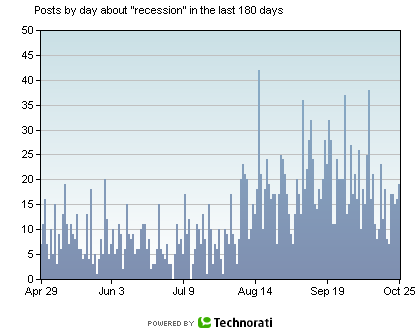

First, a look at what the blogosphere is thinking about recession.

Figure 1: Count of mentions of recession by weblogs with “a lot of authority”, accessed 25 October 2007.

This article from the Wall Street Journal, predicting the next recession, was quite striking:

Three-Ingredient Recipe for Recession

David Wessel, October 25, 2007; Page A2

When we look back next year at this time, it will be clear what caused the recession of 2007-08. It was basically a triple whammy: Housing prices kept falling, oil prices kept rising and both lenders and borrowers grew more cautious after five years of incaution. The combination was simply too much even for the impressively resilient U.S. economy. The Federal Reserve saw it coming, but couldn’t move swiftly enough. Still, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s interest-rate cuts helped keep the recession as short and mild as those of 1990-91 and 2001.

There are three rules to keep in mind when reading a recession prediction.

- Rule No. 1: Forecasters rarely call the turn in the economy accurately. Even the wisest business-cycle veterans have a hard time. “There are forecasts of thunderstorms and everyone is saying, ‘Well, the thunder has occurred and the lightning has occurred and it’s raining.’ But nobody has stuck his hand out the window,” then-Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan told Fed colleagues on Oct. 2, 1990, transcripts reveal. “And at the moment,” he said, “it isn’t raining. …The economy has not yet slipped into a recession.” Much later, arbiters at the private National Bureau of Economic Research determined a recession had begun that July.

- Rule No. 2: Once forecasters start shaving their growth forecasts, they tend to keep shaving them. At the end of August, economists surveyed by Macroeconomic Advisers, a St. Louis forecaster, predicted the U.S. would grow at a 2.7% annual rate in the fourth quarter; last week, they were betting on 1.6% growth.

- Rule No. 3: There are always good reasons to argue, “This time it’ll be different.” But “this time” is usually different in specifics, not in the overall outcome.

The housing story is painfully clear. A June WSJ.com survey found that by a 3-to-1 ratio economists thought the worst of the housing bust was behind us. They were wrong. Housing kept sinking. Housing starts in September were 26% below year-earlier levels. That’s a direct hit to economic growth.

Falling housing prices are a second hit. The price of the median existing home sold in September was down 4.2% from a year earlier. That is reducing household wealth, shaking confidence and increasing foreclosures. That’s significant because today’s recessions are triggered more by collapsing asset prices — the bursting tech-stock bubble in 2001, for instance — than by the old cycle of retailers and factories reacting to rising inventories of unsold goods by curtailing orders and production.

“Only twice have we had this kind of housing collapse without a recession, in 1951 and 1967, and both times the Department of Defense came to the rescue, because of the Korean War and the Vietnam War,” Edward Leamer of the University of California, Los Angeles, told the Federal Reserve’s Jackson Hole, Wyo., conference in August. Mr. Leamer and his UCLA forecasting team say this time will be different. They predict “a near-recession experience,” but expect factories, aided by export orders, to avoid recession-inducing layoffs. (See Rule No. 2.)

…

… But coming on top of housing and energy, the understandable desire of lenders to be a bit more tight-fisted is likely to turn what might have been painfully slow growth into recession.

Now, recall Rule No. 1. What could prove me wrong? Mr. Bernanke talks hopefully about a “two-speed economy” in which housing remains weak and the rest of economy remains strong. After all, the best guesses are that the U.S. grew at significantly better than a 3% annual rate in the quarter ended Sept. 30. The continued boost to U.S. exports from a weakening dollar and continued economic vitality in Europe and Asia could yet offset the triple whammy. But global growth prospects, except for China, look gloomier than six months ago. And, at home, the job market could continue to be strong enough to give consumers the wherewithal to keep spending.

But that’s not the story I expect to be writing in October 2008.

The external aggregate demand link is an interesting one to me. There’s no theoretical reason why net exports couldn’t keep the U.S. out of a recession, and indeed this is critical to the decoupling hypothesis. This article from Reuters is one of the most recent (and emphatic) explications of this view:

Economists smile as greenback drops

Thu Oct 25, 2007 12:30pm EDT

By Emily Kaiser

WASHINGTON (Reuters) – The swift decline in the U.S. dollar is addressing two of the most worrisome problems facing the U.S. economy — a gaping trade deficit and looming slowdown — with few ill effects.

Far from calling for any intervention to prop up the greenback, which has fallen some 8 percent against a basket of currencies this year, many economists argue that an orderly slide is welcome, and perhaps one key to ensuring an economic slowdown does not mushroom into a full-blown U.S. recession.

“Why should the U.S. worry about the danger of a dollar meltdown? It’s the solution, not the problem,” said Brian Reading at Lombard Street Research.

Reading estimates that the dollar’s decline will cut $155 billion off U.S. foreign debt this year, as well as boost exports, supporting the domestic economy while reducing gaping trade imbalances that have long frightened economists.

The dollar has been on a downward slope for some five years, but the decline steepened in recent weeks as worries about a U.S. economic slowdown have grown. The dollar (.DXY: Quote, Profile, Research) hit a record low against a basket of currencies on Monday.

This spurred me to wonder whether external demand has ever prevented the United States from slipping into a recession. I think this is a hard question to answer correctly; it would require a full fledged macro model — and agreement on which model to use (agreement on which is lacking). So I decided to do something more modest, namely, to look at the growth components of GDP, in a sort of accounting exercise.

Figure 2 depicts real GDP growth and the net exports contribution (both in percentage points, SAAR). Figure 3 depicts the domestic absorption component of GDP growth (consumption, investment and government spending on goods and services) and the net exports contribution.

Figure 2: Real GDP growth and contribution of net exports, in percentage points, SAAR. NBER-defined recessions shaded gray. Source: 27 September 2007 BEA NIPA release, and NBER.

Figure 3: Real domestic absorption (C+I+G) growth and contribution of net exports, in percentage points, SAAR. NBER-defined recessions shaded gray. Source: 27 September 2007 BEA NIPA release, and NBER.

Notice that there are only a few instances where the domestic components growth contribution go negative, and the enet exports growth contribution goes positive, and the U.S. economy is not in (a NBER-defined) recession: 69Q4 (just before the 1970 recession), 73Q3 (just before the ’73-75 recession), 79Q4 (just before the ’80 recession), 81Q2 (just before the ’81-82 recession). (There are multiple instances where domestic absorption goes negative, net exports go positive and the U.S. is in recession.)

Now, the times, they are a-changin’. Trade is a bigger share of U.S. GDP. Many argue the rest-of-the world is in much better shape this time around (emerging markets growing (but see here), Japan not yet in recession, Europe still growing.) One could then plausibly argue that one should look at exports. Moreover, because imports fall during recessions, one should check to see if exports — rather than net exports — are what prevent recessions. Figure 4 depicts the domestic absorption growth contribution against the export growth contribution.

Figure 4: Real domestic absorption (C+I+G) growth and contribution of exports, in percentage points, SAAR. NBER-defined recessions shaded gray. Source: 27 September 2007 BEA NIPA release, and NBER.

Only in 73Q4, 79Q4, and 80Q2 is the export growth contribution positive at a time when the domestic absorption growth contribution is negative, and the economy is remains out of recession. The rest of the instances where absorption and export contributions fit this configuration, the U.S. economy is in recession.

It’s also interesting that in the last recession (2001Q1-Q4), exports fell; this can be partly explained as the worldwide fall in business fixed investment associated with the dot.com bust. One could argue that there is nothing of a similar nature on the horizon. One question I would have in this regard is whether the world-wide ABS-induced credit crunch and housing slowdown (WSJ, sub.req.) could fulfill a similar role.

I want to stress this is not proof that external demand can not prevent a recession. (Thinking in a Keynesian framework, the autonomous component of exports should have a multiplier effect that shows up in domestic absorption, for instance.) What it does indicate is that net exports, or exports, have not — in a mechanical, accounting, sense — typically kept the economy out of recession when the combined contribution of consumption, investment and government spending growth goes negative.

Technorati Tags: domestic absorption,

recession,

net exports,

exports,

housing.

What is keeping us out of recession is the stimulative effect of foreign central banks buying our debt. Certainly their loose monetary policy aids our exports. But perhaps more important is it effect of artificially lowering our long-term interest rates.

You’d have to be a pumpkin head to loan the US gov’t money for 10 yrs at 4.3%

One of the structural changes behind the great moderation is the role of imports in inventory corrections. Just as we have seen over the last year when retailers, etc, have to reduce inventories a much greater share of the adjustment now occurs through a drop in imports rather than a drop in demand for domestic good. We now export much of the inventory correction and a drop in imports shows up as an increase in gdp. so you might want to do the same exercise with imports contribution to gdp growth as you just did with exports.

Menzie, I have a simple thought experiment that should answer this question. Suppose that the domestic economy consists of whatever it consists of, but that the export economy is represented by a single factory. Suppose that that factory requires no additional labor, purchases no raw materials in the domestic market, and can scale up from 0 to infinite production without any costs besides raw materials. In this economic model, domestic growth could rise or fall without impacting exports (except through the costs of raw materials), so GDP could rise even as the entire economy except the export factory was in dire recession. So, this model represents the maximum extent of decoupling; to the degree that commodity prices are elastic, it may be completely or partially decoupled.

Realistically, the export “factory” competes with the domestic economy for raw materials, land, labor, and all the necessary inputs. So, the degree of decoupling depends on the nature of the export economy and the various elasticities.

To a large degree, the US has decoupled labor inputs by using overseas production for low-tech production and bringing in technically-trained people through the H and L visa programs (not to mention the 12 M undocumented workers; immigrant labor only partially participates in the US economy, since a large portion of income is generally remitted abroad). That leaves the coupling to the domestic economy largely through commodity inputs.

As simple as the model of this thought experiment is, I think it provides qualitative insight into the nature of economic coupling that exists. The reason I consider the dollar to be the hinge on whether the economy enters recession or not is that so many products used in the consumer economy are produced abroad– and, like oil or toys, will continue to be produced abroad even if the dollar falls more– that price hikes will hit consumers hardest of all. So, Boeing may be doing very well even as its employees are forced to skip holiday gift giving.

Good, thought-provoking piece, Professor; thank you.

The tricky part, as you well now, is how will foreign business and foreign consumer demand hold up in the face of falling demand in the U.S. for their products. My gut sense is that it will not hold up: economic factors (high househuld debt to income) are tamping down consumer demand in the U.S., which is pushing down consumer confidence. The fall in U.S. consumer confidence will spread to foreign consumer markets, also, I expect.

Very interesting. Much would seem to hinge on the extent to which the US problems spill over to cause a global slowdown/recession.

It might help matters if China increased its domestic demand for imports, partly by letting its currency rise, so that they could pick up some of the ‘buyer of last resort’ slack from US. Under the circumstances, maybe they could portray such a move as an act of global economic statesmanship – part of their “peaceful rise” – instead of as a cave-in to foreign pressure.

You know, there’s something I’ve wondered a lot lately. Exactly how well does the accounting of the current account reflect the reality of globalized companies? Here’s a couple of examples:

Intel may produce a whole ton of chips in say China or Ireland and have sales outlets in all different countries. So they sell a whole bunch of chips worldwide. But they’re also producing them in foreign countries, which would seem to create the possibility that there are earnings owned by American companies that are held offshore in large amounts for tax reasons and don’t generate any “export” numbers, even though there is massive benefit to American shareholders. The result would seem to overemphasize the danger of the size of the current account. The tell should be in the size of owned assets foreigners own here and what we own over there, which curiously has fallen in the favor of US assets over the last several years (not numerically, percentage wise). Now, there are a few reasons for this… Foreign equities have done wonderfully (and US ownership is much more equity in nature) and the drop of the dollar. However, it would seem somewhat counterintuitive considering the size of the deficit.

Another example would be say Coach opening a store in Japan (if we’re going to export anything, it’ll be consumerism. We got that one nailed). But I don’t see how success of that will actually end up registering on the trade balance. The store will exist overseas, manufacture overseas and sell overseas. So where’s the import/export component that helps us out. It’s “just earnings” that we gain. But earnings *are* nice aren’t they?

So the embedded questions here are: How well does the trade balance take into account this type of environment and how does it work for the examples in particular? One of the things that scares me, is the idea is that if we need to devalue the dollar, what actual benefit it will render? Manufacturing, for the most part, is not done in the US anymore. What manufacturing base are we going to depend on to help erase the massive trade imbalance — you don’t just invent a manufacturing sector that doesn’t actually exist overnight. Plus, if companies believe that the devaluation is non permanent, they’re not going to make investment as if it is, even if they get an earnings stimulus that’s nice. I already can tell in investing, that the dollar devaluation is not as nice as you might think. The first thing I do is figure out the currency component and discount it as anomalous.

I have posted a chart illustrating how US Net Exports actually improve during recessions.

See “International Trade and Recessions”

http://www.wrahal.blogspot.com

You’re exactly right Will, we can erase the trade deficit through recession and by a subsequent lack of demand to buy any products anywhere. Not exactly what I’m hoping for.

Menzie,

Thanks for this post and topic. I agree with your conclusion though for different reasons.

Let’s look more closely at the comments. First David Wessel

When we look back next year at this time, it will be clear what caused the recession of 2007-08. It was basically a triple whammy: Housing prices kept falling, oil prices kept rising and both lenders and borrowers grew more cautious after five years of incaution.

Each one of Wessel’s triple whammy has been caused by the FED and FED mistakes managing monetary policy. Housing prices were pumped up by lower interest rates and monetary injections (Greenspan going out with a bang?), and then the FED pulled the rug out buy pushing interest rates back up.

As the FED pumps in more liquidity oil continues to climb due to inflation. If you look at gold you will see why the price of oil is increasing.

Then lenders are more cautious because there is no consistency at the FED. Lenders fear that the FED will set them up once again for a fall.

Then Emily Kaiser rejoices because of this decline in the value of the dollar and the increase in inflation. At the current rate of decline in the dollar we will be very soon fighting the same inflation demon we fought in the 1970s. Increased exports, combined with decreased imports, is not a good sign but an indication that the economy is slowing. If you look at the poorest economies they are net exporting economies because they cannot afford imports.

The bottom line is that intervention by the FED has distorted monetary conditions and is creating a worse problem than we had a year ago. Bernanke has invoked his “financial accelerator” and has sent his financial shock into the economy in the form of massive liquidity: 1/2 pt decline in the FFR, huge increase in base money, and gold and oil flying through the roof.

While there is a market boom right now hold on to your hat because the bust is going to be a big one.

The problem with this analysis is the limited time horizon of the data. Data from 1900-1970, when the US had higher net exports relative to GDP would probably show periods where change in net exports were a greater contributer to GDP growth than domestic absorption. That said, the economy spent much more time in recession in that time period, so it may not have prevented a recession outright, but exports may have significantly cushioned a recession.

Tyler,

During much of the period you mention there was virtually on international trade.