This post recaps a post from over a year and a half ago, in light of surging oil prices. Most attention is rightly focused on the supply side effects of the increase in the real price of oil. However, another facet is the impact on transportation costs, and hence the tradability of goods across borders.

Figure 1: Log real oil prices (West Texas Intermediate), deflated by CPI-core (blue) and CPI-all (red). Source: FRED II.

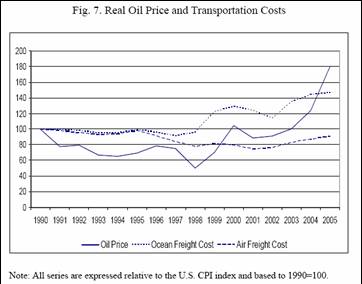

As I noted in this post, while we are accustomed to thinking about trade costs as monotonically declining, this is not really the case. As Glick and Bergin pointed out, transportation costs depend significantly on oil prices. As transport costs go up, price dispersion rises. The link between transport costs and energy prices is depicted here:

Figure 2: Source: Bergin and Glick (2006) [pdf].

Bergin and Glick note that ocean freight has been rising with oil prices. In contrast, as late as 2005, air freight was still lower than what it had been in 1995, albeit rising. BLS price indices for air freight suggest the higher oil prices have indeed fed into higher transport costs.

Figure 3: Log (nominal) inbound airfreight prices (blue) and log oil price per barrel (WTI). Source: BLS and FRED II.

One has to be careful to take note the two vertical axes are different. Since 1998Q1, nominal oil prices have rise 180% in log terms, while nominal inbound air freight prices have only risen 40%.

Several implications flow from these musings. First, more goods will now be “nontraded”. This would lend more “home bias” to US consumption (and more home bias to each other countries’ consumption, as well). Second, one might think that as transport costs rise, foreign and domestic goods would become less substitutable, holding all else constant. In terms of the macro parameters, the price elasticities of trade flows [1] should be become smaller in absolute value terms, although I would suspect that such an effect would be almost impossible to detect econometrically.

To the extent that the development of cross border supply chains relied upon low trade costs and rapid transport, higher oil prices should be expected to retard this process.

There could be some interesting investment opportunites from this development.

For example, which companies have the biggest, most efficient cargo ships? Rail is way more fuel efficient than trucking, should be some substitution that way. Probably rail equipment manufacturers could pick up business, anything that makes rail transport more efficient is going to get a huge NPV boost.

The EJ&E merger with Canadian National looks huge. If that goes through, CN can effectively bypass the world’s biggest rail bottleneck: the City of Chicago.

Sorry, my brain has been permanently warped by “Fast Money” on CNBC.

Makes sense, your conclusion, Professor.

And, if you see the world as I see it — dollar crash upcoming — we’ll see oil skyrocket here in the U.S., while, paradoxically, it will be relatively cheap next door in Mexico and Canada.

And, due to our sky high household and government debt, we will live in a country that will have greatly reduced its outlays on consumption.

So, our reduced consumption will be met wherever possible by local supplies, due to the high import costs: high transportation costs and toasted dollar.

It’s a dreary outlook, but realistic, and is how I see the macroeconomic data playing out.

I’m missing a grasp of the magnitudes here.

If ocean transport is a very small per cent of total cost, it could rise steeply without impacting global trade. Could you elucidate here?

Indeed, if truck transport rises more steeply than ocean transport, because it is more energy intensive, the effect could be to disperse manufacturing within the USA, relative to American markets, rather than to diminish ocean transport.

Hello,

I am an economist who works within the transportation industry, I make my money on transaction costs and a decrease in imports has already been felt within my industry.

Fuel costs make up 60% of the total costs faced by shippers. Fuel has risen from $306 a metric ton to over $500 in the past year alone.

To combat the situation, we have noticed that shippers are slowing the speed of their vessels to conserve fuel.

To answer some of the questions from the comments above:

Maersk is the most efficient and largest international shipper and their international ports are a thing of beauty.

While rail is more fuel efficient than long haul trucking, rail is at capacity and the infrastructure is difficult to develop and finance. Many of the railroads still behave like monopolists and have little incentive to change even in the face of market forces.

The weak dollar and reduced consumer spending, coupled with high oil prices mean than less demand is expected, which to a certain extent is beneficial since it will cost more to ship goods; a recession seems to be particularly well timed in that aspect.

Had demand increased in the face of higher transportation costs (a decrease in the supply of goods, since the more marginal suppliers would have been forced from the market), then we would have had a double shift which would lead to drastically higher prices.

However, since supply decreased and demand decreased, there is the potential for prices to remain somewhat unchanged, since the two forces are working in opposite directions.

For a look at the situation from people on the ground, please visit my blog http://inlandecon.blogspot.com/2008/03/pulse-of-ports-peak-season-forecast.html

There is precious little spare rail capacity in this country, and nearly zero chance of additional investment in same – since freight trucking is still excessively subsidized and rail can’t condemn new corridors even if the subsidy equation equalized.

Interesting reply, galvin2. Thanks for the link.

Is Globalization a relatively new political process or simply a fancy metaphor for the integration of the global capitalist market system that has been in the works for centuries now?

The political evolution is irreversible.

I would be curious to know if high oil prices reduced trade and investment in the early 1980s. I don’t recall ever seeing that in the data. If past experience is any guide, fuel saving innovation should blossom over the next few years.

I think that the united states dollar will soar in the second half of 2008. Higher transportation costs mean more US buying. In addition, I think that the fed wont cut as agressively and all the monetary and fiscal stimulus willy lead to growth in the economy after the present slowdown/recession. These factors will lead to a rebound in the dollar.

I hate to keep referring to James Kunstler because he is so prejudiced against suburbia that it kind of taints his whole line of thought. Nonetheless, his idea that outrageously high energy prices (assuming they come about) are bound to restrict trade of many items. e.g. I live in Minnesota and we are very used to getting veggies and fruit from all over the world even in the winter. This might become very difficult to impossible. In related thought, his idea that air travel will become far too expensive for anything but long distances and only for the wealthy (not presumably fruit and veggies) might already be coming true as we watch airlines cut domestic capacity and add int’l. Let’s hope Kunstler is wrong about his big picture though – the total collapse of American society at least as to where we live.

I suppose it is natural to assume high energy prices would retard the growth of international trade. There are so many other factors at work in civilian commerce, I strongly doubt that it is materially relevant.

However, the question to ask is will high energy prices slow or stop western colonial ambitions? (Nuclear weapons are close to useless on the ground though diplomatically and politically they serve to underline well understood hypocracy and inflame anti-American and anti-Israeli passions.) Modern armies still run on diesel fuel and kerosene. Colonialism requires boots on the ground. It cannot all be accomplished by efficient, politically safe aerial bombing.

Here is another way of asking the same question: Have changing material costs ever shocked imperial systems and colonialization in any noticeable way?

In the beginning, a whole series of technical developments allowed Europeans to spread out and conquer. However, Europeans did not abandon previous colonial possessions and ambitions because of material costs. They abandoned aggressive colonialism because of increasing social costs.

The material costs of contemporary US and Israeli colonialism since 1967 have been utterly enormous–trillions of dollars of foregone social wealth. Elsewhere, for example, the open-access style demographic flooding of Tibet and Inner Mongolia may have left substantial wealth on the table but one can safely presume that negative impacts on North Americans and Europeans have been minimal.

Menzie Chen: I suppose the kill-take/negotiate-exchange policy decision is a BIG PICTURE issue, and ordinary international civilian commerce is a SMALL PICTURE issue. But then you use these BIG PICTURE metaphors to ‘hook’ your readership…. Funny about the BIG PICTURE, it is always there, even if so-called liberal economists like colleague Paul Krugman seek to judiciously dance around them.

Interesting post and interesting comments. I wrote a summary and a short discussion which can be found on my blog .