Yet another week of institutional changes that render all those nice macroeconomic texts and professors’ lecture notes obsolete.

The interest rate at which banks lend their Federal Reserve deposits to one another overnight is known as the fed funds rate. For the last 20 years, U.S. monetary policy has been primarily implemented by setting a target for this interest rate. Changes in the Fed’s target are widely discussed in the financial press as key economic developments.

There was yet another announcement from the Fed this week that caused my jaw to drop, though you’d think I’d be getting used to such surprises by now. The Fed announced on Tuesday that it will raise the interest rate it pays on both required reserves and excess reserves to the level of the target itself, currently 1.0%.

My first reaction was, How in the world could that work? Why would any bank lend fed funds to another bank at a rate less than 1%, exposing itself to the associated overnight counterparty risk, when it could earn 1% on those same reserves risk free from the Fed just by holding on to them? It would seem paying 1% interest on reserves should set a floor on the fed funds rate, so that any fed funds actually lent between banks would have to offer a higher rate than the official “target.”

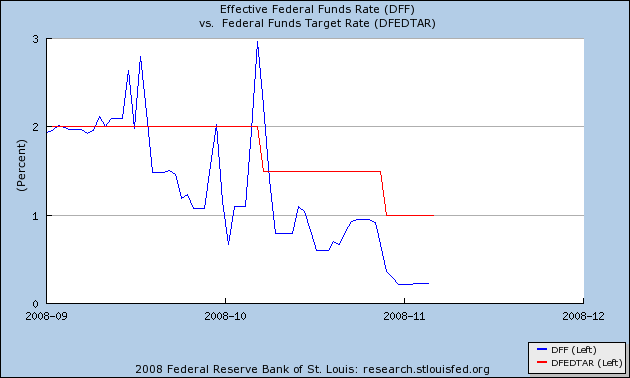

But I’ve always been more persuaded by facts than by theories, and the effective fed funds rate reported for Thursday– the first day of the new regime– was 0.23%. So much for that theory. But what’s going on?

The answer begins with the observation that the GSEs and some international institutions also have accounts with the Fed. But unlike regular banks, these institutions earn no interest on those reserves, so they would in principle have an incentive to lend out any unused end-of-day balances as long as they earn a positive interest rate.

But that’s not a sufficient answer by itself, because there’s an incentive for any bank that is eligible to receive interest from the Fed on reserve balances to borrow those balances from the GSE at a rate less than 1%, get credited by the Fed with 1% for holding them, and profit from the difference. Why wouldn’t arbitrage by banks happy to get these overnight funds prevent the rate paid to the GSEs from falling below 1%?

Wrightson ICAP (subscription required) proposes that part of the answer is the requirement by the FDIC that banks pay a fee to the FDIC of 75 basis points on fed funds borrowed in exchange for a guarantee from the FDIC that those unsecured loans will be repaid. If you have to pay such a fee to borrow, it’s not worth it to you to pay the GSE any more than 0.25% in an effort to arbitrage between borrowed fed funds and the interest paid by the Fed on excess reserves. Subtract a few more basis points for transactions and broker’s costs, and you get a floor for the fed funds rate somewhere below 25 basis points under the new system.

|

Under this regime, the effective fed funds rate– a volume-weighted average of the rate associated with fed funds traded on a given day– would come in above the target if it is dominated by actual banks borrowing fed funds, and below target when dominated by GSE lending. In the latter case, the effective fed funds rate would seem to be a particularly meaningless statistic, reflecting nothing more than the institutional peculiarities just detailed.

That means a couple of things for Fed watchers. First, fed funds futures contracts, which are based on the average effective rate rather than the target over a given month, are primarily an indicator of how these institutional factors play out– how much the effective rate differs from the target– and signal little or nothing about future prospects for the target. Second, the target itself has become largely irrelevant as an instrument of monetary policy, and discussions of “will the Fed cut further” and the “zero interest rate lower bound” are off the mark. There’s surely no benefit whatever to trying to achieve an even lower value for the effective fed funds rate. On the contrary, what we would really like to see at the moment is an increase in the short-term T-bill rate and traded fed funds rate, the current low rates being symptomatic of a greatly depressed economy, high risk premia, and prospect for deflation.

What we need is some near-term inflation, for which the relevant instrument is not the fed funds rate but instead quantitative expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet. I continue to have concerns about implementing the latter in the form of expansion of excess reserves, which ballooned by another quarter trillion dollars in the week ended November 5. Instead, I would urge the Fed to be buying outstanding long-term U.S. Treasuries and short-term foreign securities outright in unsterilized purchases, with the goal of achieving an expansion of currency held by the public, depreciation of the currency, and arresting the commodity price declines.

But the last thing we should expect to do us any good would be further cuts in the fed funds target.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

economics,

Federal Reserve,

interest rates,

credit crunch

What about the sure collapse in the dollar if we do that. One would think China would sell dollar assets like crazy and drive up long term rates a lot faster than the Fed could get them down. That would raise mortgage rates and drive house prices down further.

Jim: I had a long discussion with a number of readers about the dollar collapse issue here. My basic view is that there’s a middle ground between severe deflation and severe inflation, and that this middle ground is the place to aim for. I’m proposing that you watch the exchange rate and rein back if the dollar starts to slide significantly. And the primary objective is not to lower long-term yields, but to raise short-term yields.

My view is that the rate of change over the past 120 days in the USD has worked against the reflationary efforts, in addition to the USD’s absolute level as measured by the USDIndex. If one is therefore advocating for monetization of the long end of the curve, then one would hope the USD’s ascent would at the very least be arrested around current levels. And frankly, some easing back down below the 80.00 level would be commensurate with levels in Q1 and Q2 which showed some support for the US economy via exports. What’s clear to me is that the USD provided an extra negative shock to Q3 performance of the US economy.

Going forward, I have written elsewhere that a new Obama admin needs to be very careful in both stagecraft and policy how they use Rubin and Volker–as the former is associated with a strong dollar and the latter as an inflation fighter.

To say the we need neither of those policies right now would be an understatement.

Gregor

That discussion was real interesting. I hope Roubini and Mish are wrong – they seem to take such pleasure in their prediction of doom. I do share the concern that the fed will wait too long – but as one smart poster said – it is easy to forget that the Treasury (fiscal policy) will also be involved – and that confidence is thus not really an issue.

Reading your excellent post I still have a problem trying to understand Why FED increased rate for excess reserves?

Is it the same situation when FED increased it from target minus 0.75% to target minus 0.35?

It would be useful for me to understand this point.

Thanks.

We can just spend on the scale of WWII – on clean energy. That will work fine.

“But the last thing we should expect to do us any good would be further cuts in the fed funds target.”

I don’t understand this. If the explanation is correct, then arbitrage borrowing shouldn’t occur if the target rate drops to 75 basis points or below, should it? The effective rate should track the target rate more closely – i.e. it should now increase if the target is 75 or 50 basis points for example. So target policy should be more binding in the range [0, 75] basis points.

Why doesn’t the Fed just pay interest on the GSE balances? It seems the existing arrangement is dysfunctional and even embarrassing in terms of not having an effective rate that tracks the target (there was no problem like his prior to big excess reserve settings or payment or interest on reserves).

Also, I’m surprised that the FDIC insures fed funds borrowing, which is normally not considered to be a deposit.

JKH: non arbitrage condition means:

Effective rate = target – 0.75%

So at the end, whatever be the target rate arbitrage condition is independent of the rate level.

Gents-

It makes perfectly good sense to me that the FED should continue to sterilize their liquidity injections…. The reason being, that the banking system IS NOT INTERESTED in re-inflation when loan losses are being absorbed… Creditors’ interests are best served in a deflationary scenario where assets can be acquired at low cost.

The fact that the FED is now providing interest on reserves while the FDIC is collecting 75 bps to insure the deposit looks to me like a method for the FED to subsidize the FDIC… I suppose we have to put up with these antics, because no one in power wants to disturb market confidence with a direct injection into the FDIC… I think that the only one they’re fooling is themselves.

Thanks for the great post! Very insightful, indeed!

The explanation why the effective rate comes in at ~25bp due to GSEs (didn’t know that one!) and FDIC (..neither that one..) seems plausible. [even tough the intraday high is still >=1%, but probably the market is quite “binary”: either 100bp]

Does the Fed provide data for the volume in the fed funds market? If the GSEs and some international banks are the only ones left there I would expect the volume to be much lower than a few months ago.

Could you recommend some further reading regarding the fed funds market/open market operations (books, websites, whatever)? I was quite surprised to hear the FDIC provides insurance for the fed funds market (on the other hand I always wondered why formally “unsecured” fed funds rates are so low compared to equally unsecured Libor rates, FDIC insurance is surely the answer to *that* puzzle).

Professor,

Another outstanding post!

Thank you for understanding the problem created by a floating currency that creates whiplash changes from inflation to deflation.

I do differ with you concerning the indicator used to determine when adding liquidity is necessary and when it has reached its limit. You say, “I’m proposing that you watch the exchage rate and rein back if the dollar starts to slide significantly.” This makes our monetary policy dependent on the monetary policies of other countries, other Central Banks. It would seem to make more sense to use a commodity measure so that the change in the dollar exchange value is not obscured by the fog of mistakes made by other CBs.

Using a commodity measure I would suggest that the FED has not yet reached the point of deflation though it is close. What we are now feeling is the pain of the correction of the previous inflation as it is wrung from the system, but a serious injection of liquidity at this point could actually do more harm.

There are few who do not believe there has been a serious over-investment, a glut, in the housing market caused by loose monetary policy and abnormally low interest rates. Injecting liquidity to prevent a correction will simply compound the problem like pouring water into the mouth of a drowning man.

Once a boom (bubble) ends and a bust begins – as we are apparently experiencing – additional injections of cash do not help but lead to unintended consequences. For example in our current credit crisis because of so many bad loans there is a serious reluctance to extend credit. Additional cash injections will simply be used by banks to improve their reserve positions not correct the over-investment in housing.

Additionally we are now seeing the results of the capital shortage caused by the housing over-investment as the shortage spreads to other businesses attempting to operate with scarce capital. Injections of cash will not solve the real capital shortages, but could feed inflation as companies bid against one another for the scarce capital.

What should be done is to lower production costs so that real capital can be created. This will put more goods into the market increasing sales, and lowering unemployment thereby allowing the housing market to more quickly return to an equilibrium. If the economy as a whole does not recover, the housing problem will be greater as the reduced purchasing power available for housing will be lower ,ie. economic growth will end the glut at a higher supply level of housing than would be true in a declining economy.

Because of this I have real concerns with the direction of Congress. They appear to desire to take capital from production and move it to unproductive uses such as social spending (increases in food stamp spending and increases in unemployment compensation) and government make-work programs (a “NEW” New Deal). Such spending will simply exacerbate the existing capital shortage problem creating more unemployment and more shortages of real capital.

We know that the Treasury has been selling excess T-Bills and depositing the proceeds at the Federal Reserve (the SFP.) I am assuming that these funds are available to lend to banks as well as the GSE and international institutions. Since the T-Bill rate is not far above the effective Fed Fund rate, this will defray some of the expenses that the Treasury incurs in the SFP. So the effective rate will remain low so long as the Treasury is still auctioning more T-bills.

Maxim: As I noted in the intro, these institutions have changed so profoundly in the last year that you won’t find any text that’s kept up with them. For example, the FDIC guarantee on fed funds began on Oct. 16. One of our goals at Econbrowser is to provide a resource that gives people an up-to-date intro to how open market operations work in the new environment. For example, you might look at [1], [2], [3], and [4].

Re: DickF post

Production costs must have come down somewhat already, given the drop in commodity prices including the poster child oil.

We still drive on roadways originally built during the 1930s New Deal, and having a stronger rail system, and electric grid, seem quite productive to me. As for housing, unless we inflate the dollar, housing will stop deflating the old fashioned way as folks walk away from inflated house prices and their attached debt levels. If they still have jobs, their cash flows will improve. If they lose their jobs, then unemployment insurance expansion will be necessary from a social perspective alone. I think unemployment is headed into the high teens, and only fiscal policies hold any hope of diminishing the pain.

Professor,

Excellent post. It seems your thinking is evolving on this subject: from concern over the pace of growth in the Fed’s balance sheet to a suggestion that quantitative easing can be fine-tuned using the exchange rate as a policy target. I understand the evolution. However, I think your post is indicative of the Fed’s and economists’ views on monetary policy in general. That is, both groups seem to hold to the idea that monetary policy can achieve favorable results at little cost.

In reality, reserve growth cannot be taken back easily because that would involve disposing of risk assets from the Fed’s balance sheet.

In reality, using an exchange rate target risks sending market expectations careening on a wild ride. Imagine: there is some dollar flight from easing, causing the Fed to, what? Reverse course? And what lesson would the market take from that? Of course, that it cannot count on a consistent policy of easing, and therefore deflation is much more likely.

So my point is that implementing quantitative easing without trading off inflation for deflation is very difficult – like jumping off a trapeze and landing on a tightrope. Why not be up front about this? Why not admit that one policy outcome (a moderately high level of inflation) is preferable to the other? I understand the Fed is trying to impact expectations, but at some point the lack of clarity and honesty about policy outcomes takes a toll on the institution’s credibility. Surely, after repeated statements that they “have the tools” to deal with burst bubbles, we are now at the point.

BTW, I realize that you admit we need “some” near term inflation. I think this is a matter of degree. We’ll get “a lot” of “longer term” inflation. To think otherwise is to believe the Fed can just take it all back without tanking a fragile recovery. Ironically, we’ve seen this before, in 1937 when the Fed’s attempt to take back some of the increase in reserves resulted in renewed contraction.

“Injections of cash will not solve the real capital shortages, but could feed inflation as companies bid against one another for the scarce capital.”

I guess I’m not following this logic at all. Injections of cash would make it less scarce for companies bidding for it. The availability of financial capital could perhaps create more demand for existing capital assets, causing pricing pressures there, but those assets values recently have been plunging. And, once this is stabilized, if there are modest price pressures, that just creates more incentive for the creation of new capital assets, which is much needed.

The larger problem I see with injections of cash is that it doesn’t address the structural problems which are really tying up credit markets. There is plenty of credit available for those with strong balance sheets. The problem isn’t really availability of funds. The problem is the lack of credit worthiness (or the lack of confidence in the credit worthiness) of many would be borrowers. Again, mild inflation would actually help the position of many of these net debtors, but structural improvements, including stronger regulation and transparency, will do more to restore confidence.

“What should be done is to lower production costs so that real capital can be created. This will put more goods into the market increasing sales, and lowering unemployment thereby allowing the housing market to more quickly return to an equilibrium.”

I’m not sure how you propose to lower production costs. It seems to me that more goods in the market alone would lower prices, cause lower profits, and thus lower incomes. In other words, none of this works without a corresponding increase in demand. Sure, lower prices would lead to some improved sales, but how then do you propose to push on the lever of profits first (through “lower costs”), in order to cause this trickle down?

Consider that where we are right now, there are no significant pricing pressures in the market. Labor markets have high unemployment. Capital markets have available capital, but are suffering more from structural problems and inefficiencies in capital allocation. As for raw materials, commodities markets have been pretty much in a free fall since summer.

With all of these unemployed resources, there really isn’t any downside to increased government spending to pick up some of this slack.

And, spending as a way of injecting new dollars into the system would not begin to be inflationary until it begins to create pricing pressure in at least one of those markets (labor, capital, or materials). Again, very mild inflation here could be achieved; there is no need to go overboard, just do enough to spark the beginning of another upturn in economic growth.

“Because of this I have real concerns with the direction of Congress. They appear to desire to take capital from production and move it to unproductive uses such as social spending (increases in food stamp spending and increases in unemployment compensation) and government make-work programs (a “NEW” New Deal).”

Perhaps we should consider that some of the most successful portions of the New Deal were those that did not survive for future generations. Programs like the WPA and Civilian Conservation Corps were hugely successful in helping to restore economic growth and pull us out of the depression. And they were disbanded once we got back to near full employment when the private economy was capable of better employing those resources.

Thus, temporary increases in social spending to help maintain demand should be helpful; along with needed increases in government spending in critical infrastructure areas (which in addition to creating jobs, might in the long run even help to increase productivity and produce those lower production costs you desire).

I see no way to spark instant short run increases in productivity. Short run stimulus of consumption and investment spending however, can quite easily have the economy back on track. Then we can maybe worry about reigning in excessive government spending, and the potential for crowding out of private investment. But crowding out simply can’t occur in the economy as it is right now.

Terrible, the blunt instrument that monetary policy is.

“…arresting the commodity price declines…”

That’s what we need, to bring prices for heating oil and gasoline back up, in the face of falling employment and falling income, with winter soon upon us.

I cannot wait for this corrupt system — central planning and bailout for some, central execution for others — to fail.

“What we need is some near-term inflation”

Come on, lets get real. Banks see no joy in having their loans paid off in inflated dollars. A generation of baby boomers that mostly didn’t save enough for retirement don’t see any pleasure in having their small savings gobbled up quickly by inflating expenses in retirement. The Chinese would not be happy to see a purposeful US government initiative aimed at diminishing the value of their dollar reserves, especially at a time when they need to spend heavily to stimulate their economy just to maintain internal order and calm in their population. China would retaliate (economically?) in some way. The Fed has demonstrated they can’t manage 6 months out and you expect them to fine tune monetary variables that have 18 to 24 month lags for impact on the economy. These examples could go on and on.

What we need is some job growth. That approach directly addresses multiple problems, rather than this trickle down stuff. Government funded job growth can be done many ways, quickly, and with a focus that has strategic impact, e.g. reduced energy imports.

acerimusdux,

Assume you have an economy of capital item 1 and capital item 2. The government gives a tax break for purchases of capital item 2. What do you expect to happen to the demand for capital item 1? The point is, changes in the money side of the economy does not bring the economy into balance but exacerbates the economic imbalance, think housing glut.

So consider what will happen if the government injects liquidity into the system in an attempt to return the demand curve to the pre-tax balance. Will it work? Liquidity may increase aggregate demand but when you get into the details fiscal directs the flow of the new liquidity and distortions will be inflated. The capital that is dislocated by government action cannot easily be recovered and often is simply destroyed (think partially built housing rotting away because of the bust).

Lowering production costs is simply. Reduce taxes on producers and remove regulatory barriers to entry into markets and production. The “tax stimulus” is exactly the wrong action because it prevents the market from adjusting while removing capital (through taxation – government will not just give it away) from producers.

Unbiased analysis of the Great Depression show that the government make-work programs actually contributed to unemployment. Productive workers were used to do unproductive work. Such programs as the WPA and CCC gave noting to the economy. How did the government secure the money to pay the WPA and CCC wages? You had an automobile company paying the wages of their workers on the assembly line as well as those workers walking along the road picking up trash. What does this do to the cost of production? Even temporary programs like this waste capital.

You have to look at all economic impacts of such programs not just the worker side. If your child is starving you cannot feed him by hiring a gardner.

Mike Laird wrote:

Government funded job growth can be done many ways, quickly, and with a focus that has strategic impact, e.g. reduced energy imports.

Mike,

Where will you get the funding to pay for the government jobs? You actually have three choices: 1. taxes on production 2. borrowing in competition with production 3. print the money – inflation. Each seems to actually be counter-productive.

According to the FDIC press release you linked to, the fees were waived for the first 30 days and after that, institutions can opt out of the program. So it seems that someone could set up a new bank whose only assets are deposits at the Fed, opt out of the program after 30 days, and voila! you have your arbitrage opportunity. Note that since the new bank keeps all of its funds at the Fed, it doesn’t need the FDIC guarantee since its assets are riskless.

Professor Hamilton,

Thank you for the thoughtful and instructive analysis in your blog.

I have a layman’s question. Some doomsayers argued previously that because US depends on external funding, it was impossible to do the quantitative easing you suggested. It would prompt a run on US treasury bonds and on US dollar. And it would produce hyper-inflation.

What do you think about such arguments? If you have answered them before, could you please provide links to your answers?

Gladis: A great many other readers share your concern, as you’ll see in the lengthy comments here. My basic answer, which did not seem to satisfy many readers and may not satisfy you, is that the extent of quantitative easing could be an arbitrary small number– it could be $1, it could be $1 billion, it could be $1 trillion. The claim that any choice for this number would cause hyperinflation strikes me as unreasonable. That there is a significant practical challenge in finding the right number is eminently reasonable, and hence the need for specific quantitative guidelines such as I offer above, namely carefully monitoring currency held by the public, the exchange rate, and commodity prices.

Jeff: Good point, as I discuss more here.

Don’t you guys get it that monetary policy is obsolete? It gives money to all the wealthy people who end up saving it, creating bubbles in non-productive asset trading and so on.

Prof. Hamilton, I’m confused. Does the new regime of paying interest on reserve deposits mean that the Fed Funds target rate is *more* or *less* likely to be cut to below 1% at the Dec. 16 meeting?

Professor,

Consider my comments on making our monetary policy dependent on that of other countries if we use exchange rates as our indicator. How are the countries of the world going to pay for all of their bailouts?

If the whole world inflates by 50% and we use exchange rates as our measure doesn’t that mean that we can inflation by 50% without seeing it? If we inflate by 50% and the rest of the world inflates by 50% does that mean that US prices will not increase?

Hi everybody,

I think another reason may be behind the FED move on FF market.

As everybody here well know we are facing a liquidity trap. There are different tempative ways to escape it but a solution is “avoid it while tricking the system”. I try to explain my opinion.

What do u think?

Cheers

Credit crisis doesn’t allow money to fuel economy because banks are not providing cash to other financial and non-financial companies. FED may incentive banks to keep excess reserves and use somehow that excess reserves directly for lending…

In my blog (unfortunately in italian) I argue that providing direct lending from a “lender of last resort” to non-financial companies is the only way to exit this credit crisis. Financial companies are too exhausted for doing it by herselves.