Here I survey how we got here, where things currently stand, and what it all means.

Let me begin by reviewing some first principles of what the Fed is all about. How did the cash currently in your wallet get there? You withdrew it from an ATM, perhaps. But these wonderful contraptions don’t just give you the green stuff for free– you had to have deposits in the bank to be able to withdraw the cash. You can think of your account with your bank as credits you can use to get cash whenever you want it.

But where did your bank get the cash? It likely has an account with the Federal Reserve System, which account, just like the one you have with your bank, shows a certain level of deposits that the bank has in its account with the Fed. Your bank can then go to the Fed and withdraw those deposits in the form of cash. So you can think of your bank’s deposits with the Fed as credits it can use to get cash whenever it wants.

And how did your bank come to have those deposits with the Fed? These deposits are something the Fed has the power to create out of thin air. This indeed is its primary power– the ability to create money. That’s a power that could be easily abused, so our system is set up to prevent the Fed from creating deposits willy-nilly. Specifically, the traditional operation of the Federal Reserve was to purchase assets such as Treasury securities from a private dealer, paying for them by simply crediting the dealer’s account with the Fed with new deposits. The Fed hasn’t created any wealth with this transaction, it has simply introduced a new asset (ultimately, money) and retired an old (the Treasuries that were formerly held by a member of the public are now held by the Fed).

Although private sector wealth is unchanged as a result of this transaction, there is one important implication for the Treasury. Before the Fed made this open-market purchase, the Treasury was obligated to pay interest on those securities to someone in the private sector. Now as a result of the open-market purchase, the Treasury is making that payment to the Fed. The Fed in turn returns those payments back to the Treasury. You can see those payments from the Fed back to the Treasury each month in Table 4 of the Monthly Treasury Statement.

But wouldn’t the Treasury want the Fed to simply buy up all of its outstanding debt, and relieve the taxpayers forever of that nasty burden? It might, but to do so would require so much new money creation that it would cause a horrific inflation. To avoid that, we have a careful separation of powers, asking the Fed to take responsibility for inflation and letting the Treasury worry about how to pay its bills.

The Fed could always use its power to acquire assets other than Treasury securities. For example, the Fed could make a loan to a private bank through its discount window. The bank receives the loan in the form of new deposits with the Fed, which again the Fed simply creates out of thin air. The receiving bank presumably used those deposits to pay somebody else, but that transaction simply transferred the Fed deposits to another bank, so that newly created deposits stay in the system until they are withdrawn as cash. The Fed in this case acquired an asset (the loan) whose value by definition exactly equaled that of the newly created deposits.

Alternatively, the Fed might want to add reserves to the banking system temporarily, to satisfy what it saw as a temporary liquidity need. Traditionally it would do so with a repurchase operation, in which the Fed temporarily takes ownership of an asset held by a dealer, and temporarily credits the reserves of the dealer in exchange. Essentially a repo is a collateralized short-term loan from the Fed to someone in the private sector.

There are some other categories of assets the Fed could acquire, and some other potential disposition of reserves it creates on the liabilities side. The chief among the latter that I will mention here is the Treasury’s account with the Federal Reserve. This traditionally was used by the Treasury for cash management of its receipts and expenditures. Some of the deposits that the Fed creates (for example, with a discount window loan) might have ended up being transferred between banks (as individual customers send checks to customers of other banks) and ultimately end up in the Treasury’s account (as income taxes get withheld, for example). Since the Treasury isn’t going to withdraw these funds as cash, they’re counted separately on the liabilities side of the Fed’s balance sheet.

There are a lot of other little categories we could discuss, but historically there was really just one big story– the Fed created deposits primarily by buying Treasury securities, and these ultimately ended up as cash held by the public. The left column of the table below summarizes the assets (factors supplying reserves) and liabilities (factors absorbing reserves) as of December 5, 2007. At that time, 85% of the Fed’s assets were held in the form of Treasury securities, and 89% of its liabilities took the form of currency held by the non-bank public.

| Dec 5, 2007 | Dec 17, 2008 | |

| Securities | 779.7 | 493.8 |

| Repos | 46.5 | 80.0 |

| Loans | 2.1 | 1039.9 |

| Other | 92.0 | 733.0 |

| Factors supplying reserve funds | 920.4 | 2346.7 |

| Currency in circulation | 819.3 | 877.7 |

| Reverse repos | 36.7 | 71.9 |

| Treasury accounts | 5.1 | 484.6 |

| Service and reserve balances | 16.0 | 801.8 |

| Other | 43.4 | 110.7 |

| Factors absorbing reserve funds | 920.4 | 2346.7 |

| Off balance sheet | ||

| Securities lent to dealers | 4.5 | 186.5 |

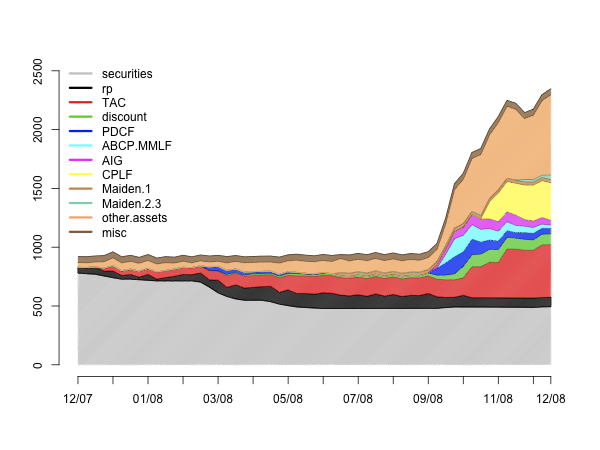

Over the last year, however, there were some profound changes in the composition of the Fed’s balance sheet. These initially were dictated by the desire of the Fed to make more loans (which it thought it needed to do to alleviate problems in the credit market) without creating any new money (which it worried would create inflation). The way the Fed sought to achieve this was by selling off a large chunk of its holdings of Treasury securities, and replacing them with loans and alternative assets. These came in a variety of shapes and colors, but the two biggest categories at the moment are the Term Auction Facility, which essentially is a systematic program to encourage a particular volume of borrowing by banks from the Federal Reserve, and amounted to $448 billion as of last week, and currency swap lines, the biggest factor in the “other” asset category reported on the Fed’s H.4.1, said other category coming to some $682.4 billion last week. Up until September of this year, the Fed was implementing these changes without increasing the total level of assets on its balance sheet. The graph below plots the composition of the end-of-week asset holdings of the Federal Reserve over the last two years.

|

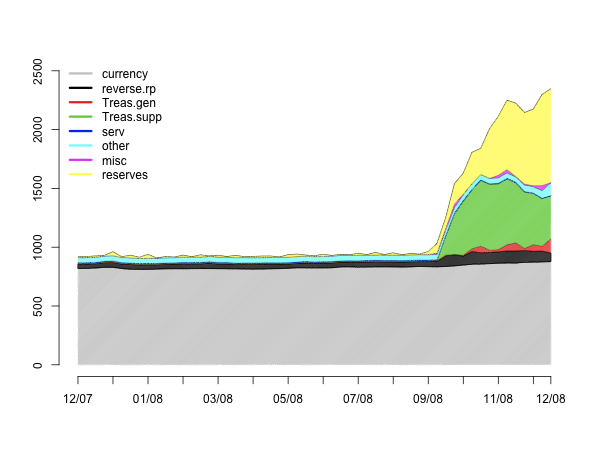

Beginning in September, the Fed decided it couldn’t afford to sell off any more of its Treasuries, but wanted to lend more and still have no effect on the money supply. To do so it needed to find a way to funnel the reserves created by the new loans it would make into categories on the liabilities side that would not result in more cash held by the public. The first such device was to reach an agreement with the Treasury for the Treasury to simply hold on to a huge volume of Federal Reserve deposits, some $484.6 billion as of last week. The way this worked is that two operations were implemented simultaneously. First, the Fed created a lot of new deposits, for example, $318.8 billion from the Commercial Paper Lending Facility alone. Second, the Treasury borrowed an additional half trillion from the public, forcing somebody in the public to send a check to the Treasury. In the aggregate, the reserves created by the Fed through the CPLF end up just being parked in the Treasury’s account with the Fed, with no creation of money. The graph below plots the composition of the liabilities side of the Fed’s balance sheet over the last year. By definition, the height of the line in the graph below is identical for every date to the height of the line in the graph above.

|

The second measure that the Fed employed to allow this ballooning of its assets was to start paying banks an interest rate on reserves that is exactly equal to its target for the fed funds rate itself, essentially eliminating any incentive for the banks to lend fed funds and encouraging banks instead to simply let excess reserves accumulate. Last week, banks were sitting on about $800 billion in excess reserves with the Fed, doing absolutely nothing with them. The Fed was in effect lending those funds in place of the banks. I have been quite apprehensive about this scheme, particularly now that we have reached a point where, in my opinion, the Fed in fact does want the money supply to increase so as to cause a little inflation. But the present arrangement makes it quite awkward for the Fed to do so.

And what’s the risk associated with the Fed’s new strategy? Back when the Fed held $800 billion in Treasuries, these were a liability of the Treasury and an asset of the Fed. In effect, the Treasury’s nominal obligation was one for which taxpayers would never owe a dime. Now that more than half of those securities have been lent or sold off by the Fed, and the Treasury has borrowed a half-trillion extra to make this work, that’s more than a trillion extra for which the taxpayers are potentially on the line. If the loans and other assets that the Fed has acquired with those funds do not make a loss, then all is still well and good. But if the Fed’s new loans do not perform, there won’t be a positive receipt in the Monthly Treasury Statement corresponding to interest returned from the Fed to the Treasury. In other words, the federal deficit will rise by the amount of the extra interest the Treasury owes on up to a trillion dollars in new debt.

And how about the Fed’s “free money” from the ballooning excess reserves? If those funds do start to end up as cash held by the public, then the Fed will need to worry again about inflation, in which case it has two options. One is to sell off some of its remaining assets (or fail to roll over some loans). In this case, the consequences for the Treasury are the same as above– that income from the Fed’s earnings is no longer coming back to the Treasury, and it’s as if the $800 billion in excess reserves was again replaced by direct Treasury borrowing.

The second option is just allow the inflation.

The bottom line is that Bernanke has made a gamble with something approaching 2 trillion. If the gamble wins, taxpayers owe nothing. If the gamble loses, taxpayers are committed to borrow a sum equal to any losses and start making interest payments on it.

For the record, let me reiterate my personal position on all this.

(1) I am doubtful of the Fed’s ability to alter interest rate spreads through the kinds of compositional changes in its balance sheet implemented over the last two years. Whatever your prior ideas were about this, surely it’s time to revise those in light of incoming data– if the first trillion dollars didn’t do the job, how much do you think it would take to accomplish the task?

(2) I think the Fed’s goal should be a 3% inflation rate. Paying interest on reserves and encouraging banks to hoard them is inconsistent with that objective, as would be a new trillion dollars in money creation.

I would therefore urge the Fed to eliminate the payment of interest on reserves and begin the process of replacing the exotic colors in the first graph above with holdings such as inflation-indexed Treasury securities and the short-term government debt of our major trading partners.

“If the gamble wins, taxpayers owe nothing. If the gamble loses, taxpayers are committed to borrow a sum equal to any losses and start making interest payments on it”

Isn’t the gamble certain to lose? Bernanke believed subprime was contained a year and a half ago; no one in government, it seems, read newspaper ads for pick-a-payment and imagined that might be a problem. Do we trust Bernanke’s gambling instincts? If the housing bubble continues to deflate – as it certainly will – and CRE, credit card debt, car loans, etc. all add to the misery, aren’t taxpayers facing decades of onerous payments. Or, will we inevitably resort to the miracle of inflation?

By the way, this is a wonderful explanation of how the Fed operates and how money is created and how this world has been changing. Perhaps it should be preserved in a side panel box: “Economic Basics”

Isn’t the gamble certain to lose? Bernanke believed subprime was contained a year and a half ago; no one in government, it seems, read newspaper ads for pick-a-payment and imagined that might be a problem.

Wow! Why is it that almost no one you see on CNBC seems to know this? All last week people were debating whether the Fed was right to start creating new money (“expanding its balance sheet”) and the dangers of inflation. But if the Treasury is just sterilizing by issuing extra bonds and holding the cash in they’re account at the Fed….

Why don’t currency traders, leading economist, and other talking head experts understand this?

Before attempting to increase inflation via quantitative easing, it is wise to consider the exit. The immediate exit problem, which you have discussed, would be how to mop up the excess of base money. The longer term problem, which concerns me, and has for the last couple of cycles, is what the policy does for moral hazard. I mean the cultural, macro moral hazard of expectations of Fed support in the event of a big fall of a popular asset class.

Since 1987, the Fed has eased in response to each financial crisis, but progressively lower interest rates have been required each time to turn the market round. Last week’s move continued that pattern.

In my opinion, the Fed must allow enough pain so that investors do not just take another run at capital gains in a few years’ time, thinking that they may have to suffer temporary anxiety, but will win in the long run. I dare say that complex spread product is not coming back, but I doubt whether houses and stocks have sustained sufficiently large losses to put gamblers off yet.

No doubt many will say that the risk of depression is too great to allow the bust to run. I recall that being said during every financial crisis of the Greenspan era.

RebelEconomist, I’m not sure about moral hazard being a problem on a macro level because the timing and consequences of any intervention is just too fuzzy to figure into any individual’s decision-making.

What got me thinking in this post though is something Prof. Hamilton already mentioned a few weeks ago: the hoarding of reserves, even in the face of spreads between the fed and the private sector rates. 800b is a lot of money even in a 14t economy, esp. considering its high-powered nature. And the reason it’s there is basically fear. It seems to me a different kind of pressure is building. Everybody is groping for the switch, it seems, but if something or somebody hits the right switch and a measure of optimism returns, perhaps accidentally, it seems the situation could turn around on a dime, or at least much more quickly than people believe today, esp in the markets.

After all, hard as it may be to believe, our ten years of drought in equity returns are actually just coming to an end. The last years were a make-believe boom, the stock market didn’t gain anything over the last, what, 8-9 years. What really happened was a huge transfer of wealth.

First, the Fed created a lot of new deposits, for example, $318.8 billion from the Commercial Paper Lending Facility alone. Second, the Treasury borrowed an additional half trillion from the public, forcing somebody in the public to send a check to the Treasury. In the aggregate, the reserves created by the Fed through the CPLF end up just being parked in the Treasury’s account with the Fed, with no creation of money.

Do we know for a fact that Treasury is issuing additional paper and depositing proceeds with the Fed? The same balance sheet would result if the Fed simply created an asset by lending money to Bank X and booked a balancing liability to Treasury.

James Hymas: It can’t just be a book entry, because reserves get truly created as a consequence of the loan, and those reserves truly have to end up in the Treasury’s account.

*ahem*

Yes, we do know for a fact that Treasury is issuing additional paper to the public. That’s Table 6 of the Treasury report.

Never mind.

I don’t know who this Karl Denninger guy is at The Market Ticker but his take sure seems a lot more plausible than all this tinkering (and it really does seem like tinkering). A lot less pleasant too.

Regarding this alleged gamble. I’m not sure that’s the right word for it. In gambling doesn’t one have a pretty good idea of odds and possible outcomes? This seems a lot more like just heaving stuff up against the wall and hoping like hell. But what do the hoi polloi know . . .

How, pray tell, can the Fed limit inflation to 3% once they start inflating? Have they ever managed to limit inflation at the same time they are trying to cause it?

When we had inflation in the range of 2-3% a few years ago didn’t they raise the specter of the dreaded deflation and proceed to blow a massive bubble?

I know – questions, questions, pesky questions. The ravages of inflation are still within the life span of most people living today. Those memories will return quickly. Suddenly deflation won’t seem so disastrous after all.

This magical belief in inflation is quite incredible. It is sad that it will take a lot of damage to challenge it. Here’s hoping we won’t need to.

With all due respect, textbook explanations are patently absurd.

“Private sector wealth is unchanged as a result of open-market purchases.”

False. Sellers no longer have a coupon payment, so the Fed pays a premium greater than remaining PV, incentivizing the seller to part with bonds in exchange for cash. Doing this in a noninflationary environment with short term securities, the premium is small. Sellers are happy to book a small profit. But attempting it in a crisis environment with longer term bonds and hyperinflation on the horizon, there is a possibility of panic selling and total collapse of the bond market. Impairment of Treasury’s ability to float more debt is right in front of our noses, whether the Fed prints more currency deposits or not.

“We have a careful separation of powers, asking the Fed to take responsibility for inflation and letting the Treasury worry about how to pay its bills.”

This is disingenuous at best. The bond market sets interest rates, not the FOMC. The only leverage the Fed had was to raise or lower bank reserve requirements — and they’ve been shovelling cash as fast as possible to shore up bank capital, accepting worthless paper as “collateral.” The Bernanke crew is in crisis mode and conspiring with Treasury to explain away the collapse of two primary dealers, insolvency of AIG and the GSEs, collapse of share prices, abrupt conversion of GS and MS to Federal banks, cessation of CP lending and global lockdown on commercial letters of credit. Both the Fed and Treasury were caught flat-footed after a full year of assuring everyone that “subprime” was contained.

“Historically there [is] really just one big story — the Fed created deposits primarily by buying Treasury securities, and these ultimately ended up as cash held by the public.”

Worse than wrong, it’s wrong twice. How was the Fed initially capitalized to start buying Treasury securities ?? and if greenbacks have any intrinsic value, are you saying that cash is backed by future tax revenue ?? Nothing could be farther from the truth. In the early 70s when I was at UW Madison, we were lectured by Fed officials that they had an M3 annual monetary expansion target of 3-5%, on the theory that cash in circulation (bank created and multiplied by lending) should mirror (or drive) 3-5% annual GDP growth — all of which was patently false. Treasury borrowing requirements drive Fed policy, the economy and private wealth be damned. We get paper IOUs backed by nothing but mounting deficits. Social Security and Medicare trust funds are nonexistent.

Alan von Altendorf: On your first point, owners of assets exchange those assets for cash all the time. It’s called the market, and the price at which they do so is called the market price.

On your second point, what exactly is disingenuous about my statement, and how do your remarks have anything to do with what I said?

As to your third point, between June 27, 1996 and June 28, 2007, the Fed’s holdings of securities went from $383 B to $790 B, an increase of $407 B. Currency held by the public went from $425 B to $812 B, an increase of $387 B. Hence it is quite accurate to claim that “the Fed created deposits primarily by buying Treasury securities, and these ultimately ended up as cash held by the public.”

JDH,

Very nice summary.

I was hoping you might clarify an aspect of the currency swaps. I haven’t seen much in the way of an authoritative explanation of the swaps effect. My expectation is that they would work through the system as follows:

Assume all other Fed balance sheet items are held constant. Then the swaps at first represent a net increase in Fed assets. The Fed creates new dollars for the accounts of foreign central banks, much in the same way it creates new dollars for the reserves of domestic banks. (I’m interested in the ultimate economic effect here more than the detailed granular accounting of the swap arrangement, so I’ll leave that out.)

The central banks then disburse these newly created dollars through their commercial systems via loans etc.

I would expect from there (and this is the part I’m mostly interested in) that the international bank clearing system clears those dollars ultimately to bank reserve accounts of banks that hold reserves with the Fed. This would work through international banking T-account analysis (Again I’ll leave that detail out).

So the ultimate effect is that swaps are a form of monetization of new Fed assets to new bank reserves. I think that part is interesting because it means the Fed’s money printing facility in the form of creating new domestically held bank reserves is truly global.

Does this sound about right?

Everything in the post is correct, and very much on the minds of every Fed watcher. The question is, what does it mean? I have what may be a contrarian view.

It seems to me that what we are seeing is simply the balance sheet consequences of the Fed’s decision to take the wholesale money market onto its own balance sheet. Banks (and other entities) that used to lend to one another, are now lending and borrowing through the intermediation of the Fed. This is so not just domestically but also internationally (the huge swap line), since foreign banks used to fund dollar asset holdings in the dollar money market.

In this view, inflation seems much less likely. Why not? If the original wholesale money market borrowing and lending was not inflationary, then why should its substitute be inflationary? Indeed, the real question is whether the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet is keeping pace with the contraction of money market credit more generally. If not, then the consequence may be deflationary.

JKH,

I will let JDH write for himself, but what you say seems right to me. I would add though that, because these swaps are so large, the pricing of them matters, and I would like to see some information on that – as far as I know, the details have not been forthcoming.

In my opinion, the Fed may believe that it does not need the free market to set rates as it can use its own balance sheet to set economic policy; this ill-perceived view is also shared by world-famous economists that believe modern central banking is stronger than market forces.

The dollar will get very weak.

Where does the public get money to buy Treasury Securities from the Treasury? Does the public sell Treasury Securities to the Fed to get money to but Treasury Securities from the Treasury? How would the public ever have enough money to fund additional govt debt? I know we transitioned from a gold standard, but how would a floating rate regime initialize if the public must sell treasury securities to get cash, but the public needs cash to buy treasury securites first?

how does fed value the assets it hold. for eg house could worth 20000 in 1950 but now it costs 200000.

Reminds me of the “Mad Hatter” in “Allice (the Feds)in Wonderland” Mirror Mirror on the Wall who is the Smartest of us ALL”

Keep your CASH close to your chest.

Voodoo economics will soon end (with a bang)

Rebel,

Thanks. We have conversed previously on the subject, and I understand your frustration with the absence of published details on pricing and swap balance sheet accounting. I would still appreciate hearing from JDH on the aspect of how the international bank clearing system flows through to the creation of bank reserves domestically. I have not seen anybody else address this.

JDH:

Isn’t there a danger that the Fed will not have enough ‘good’ assets (e.g. Treasuries) to reign in all its liabilities? Could the Fed evn end up with a negative equity position? This seems possible since the Fed has traded some of it Treauries for toxic assets or at least assets that may not hold their value.

See here

for more on this issue.

JKH: I believe your question comes down to one of exactly how mechanically the foreign central bank lends “dollars”, and I’m afraid I do not know the answer to this. Perhaps some other readers can help.

markq: When you (as a member of the public) write a check to the Treasury in order to buy a T-bill, the Fed will debit the deposits of your bank and credit the deposits of the Treasury.

satish: In general, the Fed’s assets are held at acquisition value.

David Beckworth: That is precisely my concern.

What about the other possibility? Say the treasury securites turn out to have no value. Now somewhere in what the Fed owns are lots of non-treasury securities (and foreclosed houses?). These might still have some value…

JKH,

Can you be more specific about what you want to know? I would imagine that the foreign central banks are acting effectively as agents of the Fed. The Fed lends to them via the swaps which put dollars into their accounts at the Fed. In turn, the foreign central banks lend dollars to their country’s commercial banks, into either their accounts at the Fed in the case of major international banks, or otherwise into the Fed account of a correspondent bank. Although the dollar lending auctions may be conducted in their own financial centres, the dollars are transferred in the US. I guess the operation is not dissimilar to the Fed lending to, say Citibank and then Citibank lending to, say the Ranchers’ Bank of Cheyenne, Wyoming (sorry if such a bank exists and it does have an account at the Fed!).

JDH,

On behalf of those teaching Money and Banking: “thank you, thank you very much.” –SMG

Thank you again for the detailed post that helps the rest of us catch up with what is happening.

I agree that the Fed may be creating many new problems that are as of yet unforeseen. It seems, however, that the Fed has been assuming some credit risk in order to help maintain bank solvency and to facilitate corporate borrowing (e.g., commercial paper and money market funds). Those objectives should probably be addressed with fiscal policy, but fiscal policy did not move fast enough to keep credit flowing.

What would be the consequence of deemphasizing these issues? The Fed’s actions seem to suggest it thought the consequences of waiting for Congress to act would be severe.

JDH,

on behalf of Paul Krugman und the people of the GS money club: “thank you, thank you very much.”– John Lee

JDH,

I understand the process. But let’s start at ground zero. The public has no money. To obtain base money (cash or deposits at the Fed) the public must sell Treasury Securities to the Fed. But to obtain Treasury Securities from the Treasury the public must have base money (cash or a deposit at the Fed). Sounds like a catch 22 to me. So how would such a system originate?

Rebel:

“In turn, the foreign central banks lend dollars to their country’s commercial banks, into either their accounts at the Fed in the case of major international banks, or otherwise into the Fed account of a correspondent bank.”

I agree and that’s all I really want to know – and its exactly what I’ve previously suggested would happen. It’s just that a number of otherwise thorough and excellent descriptions have been written about the nature of excess reserve creation in this credit environment and the linkage between Fed asset and liability composition – but no has touched on this particular aspect. The fact that foreign currency swaps create excess domestic reserves has been lost in the more general black hole of information on the swaps. It may seem obvious to you and me, but others who are technically curious about the rest of it seem to have passed over this part. I’d like to see confirmation from somebody who has tackled the entire Fed balance sheet subject in a comprehensive way. It seems odd to me that with the attention paid by the wonkishly inclined to the working relationship of the various pieces, nobody has completed the picture by including the mechanics of this very interesting global aspect of Fed balance sheet activity (no disrespect at all aimed at JDH’s work here, which I think is fundamentally excellent).

As the dissection of the FEDs balance sheet becomes increasingly difficult, your explanations of monetary policy have become that much clearer. Good effort.

So, just how does (what formula) the Feds technical staff quantify / calculate the correct remuneration rate on excess reserves? How do they assess the “payment on reserves” impact?

It’s a terrible theory. The money supply can never be managed by any attempt to control the cost of credit. By attempting to slow the rise in the Fed Funds rate, the Fed will always pump an excessive volume of excess legal reserves into the member commercial banks.

The problem stems from the Keynesian training of the Feds technical staff. It advises them that interest is the price of money, not the price of loan-funds. They therefore decided that the money supply could be controlled through the manipulation of the federal funds rate (the rate paid by banks to banks holding excess legal reserves in the District Reserve Banks).

Both the Keynesian concept of the “demand for money” & the “liquidity preference curve” are false doctrines.

I suppose I am the reader that JDH asks to comment about the international dimension, and I am happy to take a stab at it, with the understanding that I am making an educated guess based on available data. Here is a post of mine on the swap line: http://www.rgemonitor.com/financemarkets-monitor/254532/understanding_the_feds_swap_line

The economics of central bank swaps are very simple: each bank opens a deposit to the credit of the other, just a swap of IOUs.

The big problem that the swap line is there to address is the large quantity of dollar assets held in Europe (RMBS, and tranches of CDOs) which were financed in the dollar money market. These banks are the responsibility of the ECB (let us say) but the ECB cannot create dollars for LOLR, only the Fed can. So the Fed does, lends to ECB, which onlends to troubled banks.

That is the economics. The mechanics are more complicated for legal and political reasons.

Here is one way it might be happening (there are many others, economically equivalent):

1) Fed does swap with ECB, as described above

2) ECB trades deposit for Treasury bill newly issued, leaving Treasury with deposit

3) ECB lends Treasury to member banks, which use it to obtain dollar funding in repo market.

The end result shows up on the Fed’s balance sheet as an asset (Other Federal Reserve assets) and a liability (US Treasury, supplementary financing account). Currently the former is 628 billion, and the latter is 404 billion. So you ask, where is the missing 200? Some of this might be valuation, since the asset will be in Euros while the liability is in dollars (presumably there is some risk-sharing agreement). But the fact that the supplementary account is falling while reserve balances at FR banks is rising makes me suspect that the intermediation of the dollar leg of this swap is simply being switched from the Treasury to private banks. (Note that the economics of the swap do not require any Treasury involvement at all.)

As I have earned 484 Million US Dollars since 2000 (ABC News : http://abcnews.go.com/Blotter/Story?id=5965360&page=1), I would like to express my sincere “Thank you” to Dr. Hamilton, to the american people and taxpayers: “Thank you, thank you very much.”

Richard Fuld, ex. President Lehman Brothers

-4 + .5*3.5 + .5(-4-2) + 2

The “Taylor Rule” indicates an ex-post (3rd Qtr)

FFR of (-)3.5%. The 4th Qtr will be scary.

This interest rate formula is further behind then Bernanke’s reaction to the downswing.

Absolutely incorrect: this is not a neutral transaction. “The Fed hasn’t created any wealth with this transaction, it has simply introduced a new asset (ultimately, money) and retired an old (the Treasuries that were formerly held by a member of the public are now held by the Fed).”

The Fed has drained wealth by this operation by diluting the value of all those with a claim to production (savings). That is why the gigantic confiscation of wealth (you work, I print) has turned overt with bailouts. The expansion of money stopped and all those non-wealth creating activities suddenly find themselves short funds.

We need to immediately shut down the Federal Reserve before it becomes even worse (as it is geometrically at this point). As part of that, the Fed can monetize the existing debt to 100% while implementing a 100% reserve ratio (no sweeps), reissue gold at the prevailing exchange rate which floats freely with the dollar, and then close it’s doors. It has been a complete failure for its advertised purpose. A giant success at draining wealth, savings, and production away into the hands on non-producers and the government.

Perry Mehrling,

Are you quite sure that the ECB is lending treasuries only rather than dollars to the banks? I haven’t investigated that. If so, there would be no reserve effect in the US since the entire effect would show up as increased Treasury SFA balances (as you describe the process).

Moreover:

“But the fact that the supplementary account is falling while reserve balances at FR banks is rising makes me suspect that the intermediation of the dollar leg of this swap is simply being switched from the Treasury to private banks. (Note that the economics of the swap do not require any Treasury involvement at all.)”

But this “switch” would result in an entirely different domestic bank reserve effect, which is the subject of my question.

Treasury indeed has announced it is winding down the SFA.

So my question still hasn’t been answered directly.

Professor Hamilton writes,

“I think the Fed’s goal should be a 3% inflation rate”.

Long run real GDP growth rate appears to be about 3% per year. Add 3% inflation to that and you get a 6% nominal GDP growth rate. Maybe nominal GDP growth rate would be easier to control. It could be considered the velocity controlled money supply.

“velocity controlled money supply”

That should have read “velocity corrected money supply”

Perry Mehrling,

Sorry to be rude, but I am afraid that, despite the title of your November FT Economists’ Forum piece (on which, as a non-member I did not comment) you do not seem to understand the Fed’s swap line.

Contrary to what you wrote, a currency swap does not involve exchange rate risk. The Fed pays dollars for a dollar asset (ie it buys a dollar loan to a foreign central bank). It also sells a foreign currency loan for foreign currency to the same foreign central bank so that both sides are collateralised (more for form than substance I guess, as counterparty risk is negligible and the foreign currency is the liability of the foreign central bank concerned anyway). The unwind exchange rate is set when the swap is agreed, so there are no foreign currency gains or losses to either side as long as the swap unwinds as arranged.

Any market risk involved in the swap programme is interest rate risk, and that is why it is vital to know how the swaps are arranged. For example, if the Fed lent dollars to the foreign central banks until April 30, which the foreign central banks then lend to their banks for shorter periods, the interest rate risk matters a lot.

Okay, the Fed should essentially stick to maintaining the integrity of the dollar. How would you go about restoring credit to the US private sector?

I have been thinking about this process a lot. But I cannot get my head around one idea: How is money first created? Say in 1776? And what would I have traded for the first bank notes?

Is it a process by which the government spends the dollars on goods and services which then start into the real economy? Or were people (banks) just given money with which they could do as they pleased?

Whenever money is simply created, is the bank getting a free spin? That initial creation of money astounds me, because it seems like those closest to the Fed get a handout. In that way banks would be making the seigniorage rather than the Treasury. Can someone explain this point?

Nice expose, much appreciated. Still struggling here to fully comprehend balance sheet concepts introduced in ECON 101 over 2 decades ago!

Although inflation may have been a preoccupation of the Bernanke fed sometime ago, I have to guess that it is less of a concern with the recent federal funds rate cut to the 0-25bp range which appeard to signal panic.

As described above, (and assuming I understand correctly) steps have been taken to radically expand the monetary base (base money). However, given the on-going tendancy of banks and other agents to hoard cash or near cash instruments, that increase in the monetary base may be insufficient to get the banks to lend money unless they are threatened with a higher rate of inflation, e.g., 3%, as opposed to the sloppy 1 to 2% target that has been or was in effect. Hence the need for a new target rate. I suppose an explicit target (3%) also guards against expectations of hyper-inflation developing.

I’m not sure I’m fully grasping the situation or JDH’s proposed solution. This does feel a little like the colourful metaphor: “Up an (expletive) creek without a paddle.” Dreary.

Does someone know what is the MINIMUM effective cash reserve ratio for the entire US banking system at the present time?

As well, it would be very interesting to know what the ACTUAL cash reserve ratio is for the entire banking system.

One could thereby determine how much is the EXCESS cash reserves now held by the banking system.

Perry Mehrling,

Are you quite sure that the ECB is lending treasuries only rather than dollars to the banks? I haven’t investigated that. If so, there would be no reserve effect in the US since the entire effect would show up as increased Treasury SFA balances (as you describe the process).

Moreover:

“But the fact that the supplementary account is falling while reserve balances at FR banks is rising makes me suspect that the intermediation of the dollar leg of this swap is simply being switched from the Treasury to private banks. (Note that the economics of the swap do not require any Treasury involvement at all.)”

But this “switch” would result in an entirely different domestic bank reserve effect, which is the subject of my question.

Treasury indeed has announced it is winding down the SFA.

So my question still hasn’t been answered directly.

Rebel Economist: It is never rude to correct a mistake, and I welcome such corrections since I hate to make mistakes and like to learn. But you haven’t convinced me (yet) that I have made a mistake.

You are assuming that at the inception of the swap, it is agreed to unwind at the current forward exchange rate (derived from current interest rates in the two countries). That is a reasonable assumption, since that is the way that commercial swaps work. But there will still be gains and losses because the eventual spot rate will not be the same as the forward rate. Commercial swaps are marked to market, in order to ensure performance, so these gains and losses are spread out over the life of the instrument.

So the question is whether the Fed’s swap works like the commercial swap–I do not know the fact of the matter. I do know that some of the changes to Other Federal Reserve Assets are attributable to valuation changes–that’s what I was told when I inquired.

JKH: My guess (not certain at all!) that the swap was not affecting reserves came from watching the early days of the swap, when Treasury supplementary financing seemed to be moving more or less one for one with Other Federal Reserve Assets. Nowadays there is 200 billion gap and that gap has been filled by excess reserves of the domestic banking system. So now the swap line is increasing reserves, simply because the banking system has the deposit at the Fed, not the Treasury. The Fed does its accounting in dollars, so changes in swap valuation show up on the asset side, not the liability side.

Let’s compare the Fed’s “gamble” with helicopter money.

With a “helicopter” increase in the money supply, the Fed’s balance sheet shows a new liability, and no new asset.

That is equivalent to the Fed buying an asset, with newly-printed money, and then the asset turning out to be worthless.

In other words, if you believe that a “helicopter” increase in the money supply is what is needed to get the economy out of a liquidity trap, then the destruction of the Fed’s balance sheet net worth is exactly what the Fed is trying to achieve.

The only difference between helicopter money and the Fed’s buying a worthless asset is in who gets the money: the person who picks it up off the ground (i.e. the one who receives the government transfer payment); or the person who sold the fed the worthless asset.

Let me put it another way: if it lost the gamble, the Fed would be forced to print money to make the same monthly transfer to Treasury, and this would be inflationary. But the expectation of future inflation is exactly what the Fed needs to create now, to escape the liquidity trap. This is a gamble the Fed wants to “lose”.

I know this post will stagger those posting because of my ignorance. But I need someone with extraordinary skills of explanation to answer, please.

Let’s say, in 2005 there was 10 whatever number of zeroes you’d like to use, in dollars worldwide. At the same time the GDP (or world product if this is global) there was 10 whatever zeroes. Balance of sorts.

Now, in 2009 there’s 12 million in whatever zeroes dollars–an increase of 20%. But there’s also a global recession, so the GDP (in 2005 dollars) is only worth 7 whatever zeroes–it’s decreased 30 percent. More dollars, less production. That’s inflation, right. Production has deflated for certain, but not the amount of dollars, which has increased.

Now this assumes the 12 million can actually circulate. Maybe it can’t. Maybe the 5 whatever dollars difference between the total money supply and the lower GDP is stuck. Is this the credit crisis?

Finally, in order to avoid inflation, there’s only three ways to get back to balance. Money supply decreases to lower GDP; GDP grows to higher money supply; They meet somewhere in the middle.

When answering, please be kind.

JKH,

Evidence that you are right that the liability side of the swaps shows up in reserves is in the balance sheet asset and liability charts themselves.

You will notice that in mid to late November the swaps dropped in value and then jumped up again. (To confirm that this is indeed swaps info you can check the short positions in the Treasury’s US International Reserve Position Statement — I learned about this via Alea.)

You will also notice that on the liability side reserves behaved in an almost identical manner. So I think that this answers your question.

(In case the two links don’t come through here they are:

http://www.treas.gov/press/international-reserve-position.html

http://www.aleablog.com)

The government accumulates liabilities, the banks accumulate assets. Sucks to be a taxpayer, but great for the banks… But, what happens when “the public” is no longer willing to buy Treasuries? We have trillions in deficits around the corner, isn’t this a little short sighted? There will be an explosion of supply in the coming months and years, without significant new strings-attached-loans or money printing the yields will have to rise and this scheme will scatter into many colorful pieces as the banks once again find their assets withering away. What will they do next time?

Nick Rowe: I agree that an increase in the monetary base is a good idea. I disagree that the appropriate number is a trillion dollars, or that uncertainty about what the number is going to be is a good thing.

beezer:The money supply is measured at a point in time (it’s a stock, e.g., 12 at 5:00 p.m. EST on Dec 22), whereas GDP is measured over an inverval or time (it’s a flow, e.g. 12 per year or 1 per month of 0.25 per week). So to compare one number with the other you need to know the velocity, or number of times a dollar changes hands per interval of time you’re looking at. The velocity of money shows enough variability from year to year that calculations such as the one you’re proposing have limited predictive value in the most recent data.

Perry,

My assumption from the early days was that the swaps in full induced a reserve effect on the Fed’s balance sheet which Treasury then “sterilized” by issuing bills, putting the proceeds on deposit in their supplementary account at the Fed. As I recall, the swaps started before the Fed started paying interest on reserves, and before the fed effective rate started to “misbehave”, so that sterilization of the excess reserve effect was initially more important to the discipline of Fed monetary policy. Paying interest on reserves plus the negligible level of the current funds rate now makes it far less important.

However, this all assumes that the ECB was distributing dollars rather than treasury bills to European commercial banks.

I’ve not investigated the aspect of valuation that you say may be an issue as well. That said, I agree with Rebel Economist that the FX risk on these swaps is hedged by agreement to a contracted rate at unwinding. I’ve not investigated the interest rate risk issue to which Rebel alludes.

Uncertainty about the increase in the monetary base *is* a good thing, if the size of the increase in the money base is closely correlated with the amount that is needed, something about which we are equally uncertain.

The value of the Fed’s risky assets is correlated with how quickly the economy returns to normal. If the economy returns to normal quickly, those assets will be worth a lot, and so the permanent increase in the money base will be very small. If the economy does not recover, those assets will be worth very little, and the permanent increase in the money base will be very large. And one trillion might not seem excessive in a worst case scenario.

So you have a negative-feedback equilibrating mechanism in place, created by the Fed’s buying risky assets, the value of which is correlated with the Fed’s success in getting the economy out of a deflationary slump.

It is as if Ben Bernanke made a very large bet, backed by the Fed’s printing presses, about the future rate of recovery and inflation.

Nick,

Not sure I understand your point on “helicopter money”.

The Fed always has the option of asset backing a helicopter drop.

Why do it by debiting the Fed’s capital position deliberately?

Thanks JDH

It’s all very confusing to the average person. We’ve lost something north of $7 trillion in domestic value this year. That’s deflation, right?

Yet, as the charts above show, the money supply has increased what? Two trillion. Has velocity gone to negative? Although measurements can be “point in time,” a line of points shows a trend, no?

The money supply trend is upwards, but the pricing on assets everywhere is trending downwards. At this moment in time there seems to be a negative correlation between money supply and actual pricing of assets. How can that be?

Maybe the money is there, but it’s moving in reverse. Maybe the money is debt. And it’s being liquidated. If that’s the case, then Obama should be spending $7 trillion in ’09.

Does this all boil down to the inability of the Fed to wave a magic wand over worthless paper and make it good?

After all, if a bank, such as Citi, owns debt that has proven to be worthless, does it suddenly become worthy when it is transferred to the Fed?

Is there any problem out there besides that?

JKH: “Helicopter money” is a *permanent* increase in the supply of money (by assumption), and it adds to private sector wealth, at the existing price level, (because it’s just given away). These two features make it the most powerful form of increases in the money supply. Because it’s permanent, it increases expected future price levels (which encourages people to spend money now). Because it’s just given away, and increases household wealth (at the existing price level), you get a wealth effect on spending, not just the substitution effect (which is very weak or non-existent in a liquidity trap anyhow).

The purpose of “debiting” the Fed’s capital position is to create the expectation that the Fed cannot buy back the money, so that it is seen as permanent, and thus more powerful.

Am doing a post on this at WCI now.

ccm: “You will also notice that on the liability side reserves behaved in an almost identical manner.”

I just realized that you can’t really see this from just looking at the charts, since the supplementary/general treasuries account is also decreasing. But if you look at the 11/28 H.4.1, you find that the drop in reserves equals about 60% of the change.

I tend to think that the September through mid-November Treasury issues were not so much geared to sterilizing swaps as to sterilizing the whole of the Fed’s additional activities (including swaps).

Thanks, Nick. Will resume at WCI.

Perry,

As long as the unwind exchange rate is preset, exchange rate movements will not change the P/L of the swap, apart from potentially a second order effect.

Let’s consider the swap from the Fed’s point of view, dollar side first. The difference between the amount of dollars transferred at the beginning of the swap and returned at the end defines an interest rate, which is locked in at the outset. If that interest rate is off-market, then that side of the swap will have a non-zero MTM value. For example, if the implied interest rate is zero, the Fed will be handing over more dollars than PV of the future return of those dollars is worth, so the Fed’s side of the swap will have negative MTM value.

Now from the point of view of the foreign central bank, this would be a gift. They could lock in a dollar profit by lending the dollars to one of their banks at a market rate for the term of the swap. This dollar profit would not be affected by exchange rate movements.

From the Fed’s point of view, the purpose of the other side of the swap is primarily security. The Fed take foreign currency from the foreign central bank, again at an interest rate defined by the amounts of foreign currency transferred at the beginning and end of the swap. For precise security, the market value of the foreign currency transferred should be equal to the dollars the Fed have transferred, so that the initial exchange would typically be at the present market exchange rate. And the interest rate can be set to guarantee the Fed a foreign currency profit equivalent to the dollar profit they have conceded to the foreign central bank.

Naturally, if both sides of the swap are at off-market interest rates, the values of the forward P/L on both sides are affected by interest rates and exchange rates, but this is just a second order effect. And, conventionally, the implied interest rate of both sides of the swap is a market rate, in which case the unwind exchange rate is the forward exchange rate and both sides of the swap have no net PV.

But I doubt if that is how the swap programme works. I have not heard that the Fed is placing massive amounts of foreign currency in foreign currency money markets, so I would guess that their side of the swap implies a zero interest rate and is barely meaningful – eg if the BoE defaults on returning the Fed’s dollars, having a positive sterling balance (at the BoE?) is not likely to help the Fed much. More interesting, however, is whether the term and size of the dollar side of the swap matches the term of the loans done by the foreign central banks. If the foreign central bank drew down the full swap line for the duration of the programme, and lent out potentially less dollars for shorter terms according to its dollar loan auctions, the P/L implications for the foreign central banks are huge. In practice therefore, I suspect that a swap is established after each dollar loan auction by a foreign central bank, in which case the foreign central banks are effectively lending as an agent of the Fed. But such details should be published so that we do not have to speculate.

“One of the more confusing aspects is his assertion that the dollar swells as debt deflation takes hold. What he meant, of course, is that deflation increases the quantity of assets and the likely investment return each dollar purchases as deflation wrings debt and misallocation of capital out of the economy.”

This is from a post by London Banker. Another part of his post is:

“In the meanwhile, any wealth saved securely from state seizure will “swell” to buy more assets in future – a key aspect of deflation and a key means of restoring the control of the economy into the hands of more farsighted savers and investors.”

As for government policy, London Banker writes:

“In Lombard Street, Bagehots seminal tome on fractional reserve central banking, Bagehot advises any central bank facing a simultaneous credit crisis and currency crisis to raise interest rates. By raising rates they will ensure that foreign creditors remain incentivised to maintain the general level of credit available while the central bank resolves the local liquidity crisis through liquidation of failed banks and temporary liquidity support of stressed banks.”

Who knows? Mortgage rates have come down, and commodity price deflation is helping debtors divert income to debt reduction–which is, overtime, a reduction in money supply and anti-inflationary.

My econ courses were many years ago, so please help me understand the US situation a little better and the realistic, albeit painful, path out of this mess.

Currently, there is a warranted crisis of public and corporate confidence coupled with a justifiably blocked lending system inasmuch as the honest lenders distrust the fraudulent balance sheets of the dishonest ones that until recently thrived without sensible capitalization under deregulation. Now the Fed/Treasury has initiated opaque swaps that disastrously increase taxpayer debt if the acquired assets prove toxic.

I see the academic in- /deflationary concerns which Bernacke is attempting to juggle. What I don’t understand is how any of these current crisis mode actions address the basic problem that we are an aging debtor nation (unlike our creditor status during the Great Depression) with a false consumption-driven economy with insufficient means of production. Our adjusted real GDP has long been contracting, if the statistics weren’t finagled. The Fed’s smoke and mirror swaps with the Treasury I’d guess is in response to the waning willingness of foreign purchasers. Since Asia and the mid-East seem unable or disinterested in continuing to prop up the US, then how do we prudently address the impending implosion? Seems like the sooner we stop the madness the better able we will be to return to a more sound economy, or is that not the point?

Rebel: It is not rude to correct a mistake, and I hate making mistakes, so always glad to learn. But did I mistake? Maybe we are talking about different things?

Let us suppose that the swap is made with an agreement to pay back at the current forward rate (calculated to satisfy covered interest parity). That is more or less the way commercial swaps are written, and so at the moment of inception these are zero value instruments. But one side is going to pay euros in the future and the other side is going to pay dollars. Soon thereafter the value of the instrument changes, based on changing exchange rates and expectations of future exchange rates. One side gains and the other side loses. The ultimate gain or loss depends on whether the spot rate winds up above or below the contracted forward rate.

The Fed swap is different from a commercial swap insofar as apparently they are exchanging principle at the inception (and back again at maturity presumably)–it is an on-balance sheet gross swap, we might say. But the gains and losses will be the same. Back when I investigated this, I was told that the Other FR Assets reflected changes in swap valuation, and that makes sense only if they are marking to market or some such. I would guess that they are hoping markets will return to normal and they can close out their on-balance sheet swap by transferring to a private counterparty, so they are doing the accounting just as a private counterparty would.

JKH: My original analysis was written during the early days of the swap, when Other Federal Reserve Assets moved almost one for one with Treasury supplementary financing. If you want to say that the reserve effect was sterilized in this case, I have no problem with that. But if the Treasury is holding the Fed deposit as its asset, who is holding its Tbill liability as their asset. In my little example, I assumed that the ECB was holding.

(Yes, that was back in Sept, and it was another month or so before interest was paid on reserves.)

Nowadays, apparently the reserve effect is not being sterilized (to use your language). As you say, the Treasury is shutting down SFA. I take this to mean that the Fed used the Treasury as a short term cut-out man for LOLR of European dollar overhang, but is now transitioning to using American banking system for the same purpose.

I do not put as much emphasis on this as you seem to because I think of all this as simply a way to keep from booking 600 billion debt owed to the ECB. You and I may understand that this is just the counterpart of a 600 billion asset, but others may not. Better to owe it to the Treasury in the first place, and then to the banking system. Eventually, I would imagine that the Fed hopes to move the entire position into the private market–that is where it used to be after all.

“I would therefore urge the Fed to eliminate the payment of interest on reserves and begin the process of replacing the exotic colors in the first graph above with holdings such as inflation-indexed Treasury securities and the short-term government debt of our major trading partners.”

I think the treasury may have a word to say about the implied currency intervention contained in this advice. Which government securities would be bought? I imagine Japan, for one, would object strongly. Or are you talking about coordinated swaps?

Thanks, Perry. I think we’re on the same page re the reserve issue.

On Rebel’s swap issue, my simple take off the top would be as follows:

The Fed effectively holds a dollar asset that is constructed by swapping dollars into a Euro deposit with reversing swap back into dollars at maturity. The all-in rate is fully hedged in terms of dollar return. It should be roughly equal to the all-in rate for a straight dollar instrument, by market arbitrage and by agreed construction and pricing.

Each of the dollar swap and underlying Euro contract are subject to ongoing market value changes over the life of the contracts. If the positions are marked to market, the combined result should correlate loosely with the marked to market of the equivalent straight dollar instrument. But the components will fluctuate according to their respective markets.

At the conclusion of the contract, there is no marked to market effect in terms of the ultimate dollar yield or its components. Contracts are closed at book value and any market value differences have been amortized out between day (m – 1) and day m (maturity).

Fixed rate contracts amortize out their interim market volatility by the time maturity is reached. Specifically, the final exchange rate makes no difference to the market value of the contract because the contract has been closed at contracted book value.

Richard Pointer –

Regarding your chicken or egg question. There is always some money in circulation before central banks are created. In the case of the US, the Fed was created about 1913, at which time there was gold, silver, greenbacks, and possibly private bank notes in circulation. (Can’t remember the details of all that previous monetary history) All that previous money has been gradually retired and replaced with Fed Reserve Notes, or bank deposits.

Also, the public gets money when the govt deficit spends. Treasury sells bonds to make purchases from the public.

Richard Pointer again

“Whenever money is simply created, is the bank getting a free spin? That initial creation of money astounds me, because it seems like those closest to the Fed get a handout. In that way banks would be making the seigniorage rather than the Treasury.”

Exactly!

I’ve always thought that a bank’s ability to create money is an exorbitant privilege, which means they are essentially public utilities. This justifies their being much more closely regulated than other enterprises, and is a good argument for bank nationalization, especially in times like these.

Richard Pointer’s question got me to thinking even further back to the George Washington admin. Actually, before the Constitution and George, and especially Alexander Hamilton, the economy of the States was (or were) in pretty bad shape.

So what Hamilton (the other one) actually did was sell Congress on a massive bailout program – perhaps much more breathtaking in its scope – relatively speaking – than the ones we’re talking about now. And that’s Hamilton’s chief claim to fame (besides fighting a stupid duel).

Remember that Hamilton not only refinanced the national debt but also the debts of the States, most of whose treasuries and economies were in bad shape.

Com[plicated stuff. Was a contract written between FRB and European Central Banks before the swap was made? If so, who has seen a copy of this contract?

My naive guess is that the swaps happened too fast to write out a contract. Both sides likely agreed to hold each other harmless, in so far as that is possible.

@Richard Pointer (10:49AM)

This is something that interests me as well, and seems to be glossed over (possibly because it is irrelevant) in discussions – especially those that want to go back to the “gold standard”. Physical currency, in its most basic purpose, is nothing more than a medium of exchange. Two parties (public or private) exchange goods and services, possibly of disproportionate value and, instead of generating an IOU, a piece of paper is created whose value is equal to the IOU but redeemable with anyone who will honor it. Banks take excess IOUs and give them to others who can spend them. Thus, the cause of money is physical labor.

My issue with a gold standard, on an ideological level, is that the ability to supply labor to a system is independent of the ability of that system to procure gold (or any physical medium for that matter). The Treasury, with its ability to print money, is able to generate IOUs proportionate to the amount of excess labor in the system thus allow it to grow at whatever rate the system can naturally sustain. A large problem could be that we are generating IOUs for non-labor activities and thus devaluing the labor that is performed and remunerated. We are also, I agree, trying to supply IOUs in hope that people will choose to work and thus earn them AND spend them (thus making their creation non-inflationary). If this additional labor (or spending) does not materialize then inflation can take hold since more IOUs are available than can be absorbed with current activity (which is inevitable and desirable if the productive members of society are generating the IOUs – see below – but not if the society/government is generating them).

The short-term needs between paying factors and profiting from their output necessitates the need to create IOUs on the part of producers (of output). These IOUs are standardized and called “dollars” and physical representations are created. As producers give IOUs to their employees they “borrow” IOUs from the government and then, when they receive IOUs from the outputs of their production, they give back the IOUs borrowed and have some left over. Eventually the system could be self-sustaining (if production remains greater than consumption AND people are OK and trust the IOUs) and the government would be unnecessary. Only because of the complexities of real life is having a permanent (and generally increasing) supply of “currency” required – people are born, die, and their desire to consume changes; and does their trust of the currency. Nor does every consumer produce enough to cover his own consumption – and society frowns upon non-consumers (since they die – which is apparently unacceptable).

It is not important, because we have paper money, that current consumption remains greater than current production but if lifetime consumption becomes greater than lifetime production then, by definition, we are devaluing other’s labor because we either expect them to provide services for free (health-care) or, mainly through taxes – but also charity – we distribute excess IOUs held by net producers to cover the net consumer’s deficit. Unless we abolish all similar non-voluntary transfers the productive members of our society will continue to be devalued in order to maintain equilibrium for those who would otherwise become net consumers (which means they die).

I disagree that the TAF is a neutral transaction.. The assets that the Fed lent money against as part of the TAF were NOT assigned a market interest rate – the weasel word “illiquid” simply means that the market clearing price was not to the liking of the asset owner.

So the Fed stepped in and lent money against it at a price to the liking of the asset owner – I’d claim this was much higher than the asset would otherwise fetch – this underpayment of interest by the borrower, whilst we can’t enumerate it( since there is no market!), does actually exist.

When it was just a few billion of loans and when it was just 28, 35 day loans one could overlook this as a contributor to an increase in money supply. When the loan program has gone on for 1 year and its a trillion and more – then absolutely they’ve increased the money supply.

-K

You guys are out of my league, but I intend to study up. Meanwhile it never hurts to remind everyone that neither the FED nor any other institution has much influence over the real long-term rate of interest, which is set by supply and demand of savings for investment.

Or maybe that goes without saying.

Merry Christmas everyone!

Above stated:

*** *** *** ***

“Before the Fed made this open-market purchase, the Treasury was obligated to pay interest on those securities to someone in the private sector. Now as a result of the open-market purchase, the Treasury is making that payment to the Fed. The Fed in turn returns those payments back to the Treasury. You can see those payments from the Fed back to the Treasury each month in Table 4 of the Monthly Treasury Statement.”

*** *** *** ***

Does anyone know if there is any situation that the Fed will not return to the US Treasury the interest payment from treasury bill/bond?

I read earlier a quote from Dow Theory Letters’ Richard Russell that contradicted above:

*** *** *** ***

“Dean of the Newsletter Writers, Richard Russell:

“I still can’t get over the whole Federal Reserve racket.”

Consider the following – – let’s take a situation where the U.S. government needs money. The U.S. doesn’t just issue United States Notes, which, of course it could. These notes would be dollars backed by the full faith and credit of the United States. No, the U.S. doesn’t issue dollars straight out of the U.S. Treasury.

This is what the U.S. does – – it issues Treasury Bonds. The U.S. then sells these bonds to the Fed. The Fed buys the bonds. Wait, how does the Fed pay for the bonds? The Fed simply creates money “out of thin air” (book-keeping entry) with which it buys the bonds. The money that the Fed creates from nowhere then goes to the U.S. The Fed holds the U.S. bonds, and the unbelievable irony is that the U.S. then pays interest on the very bonds that the U.S. itself issued. (With great profit to the private owners of The Fed – – Ed. Note) The mind boggles.”

Perry,

When you say “The Fed swap is different from a commercial swap insofar as apparently they are exchanging principle at the inception (and back again at maturity presumably)”, I think you are getting confused between a foreign exchange swap and a foreign exchange forward contract. Principal is exchanged at the beginning of a commercial foreign exchange swap. A foreign exchange forward, by contrast, is an agreement to exchange set amounts of two currencies at some future date (ie like a normal foreign exchange transaction but with a settlement date delayed beyond the standard interval), which is clearly taking a foreign exchange position.

Not for the first time, JKH explains the point more smoothly than me. The key market risk in the swap is interest rate risk. To reiterate what I see as a big question: does the dollar lending by the foreign central bank match the dollar loan from the Fed via the swap? If not, the national P/L implication of the interest rate mismatch is potentially huge. For example, the swap line to the BoE is $80bn until April 30. The UK dollar auctions are for shorter terms, and participation has been declining. Imagine the interest cost to the BoE if they have committed to paying interest on $80bn for, say, five months through the swap, and struggle to lend that $80bn for shorter periods at lower interest rates. I am sure that is not how it works, but I think the central banks should explain how it does work.

markg and Richard Pointer ask, Why did the public ever come to agree in the first place to exchange an interest-bearing T-bill for a seemingly worthless green piece of paper? You can hear lots of different answers to this question (some of which are offered by commenters above). For my part, I would stress that there are substantial benefits to everybody from having an easily stored and widely accepted medium of exchange. The wealth that the Fed acquired over the years (those $800 B in Treasuries as of a couple years ago) represent a resource the government was able to appropriate because it assumed the monopoly position of providing this very valuable basis for exchange. In a growing economy, the need for transaction balances grows, and the Fed could issue a little more paper each year (and retire a little more Treasury debt each year) without causing any inflation. In the event, of course, the Fed systematically created money at a faster pace than this and did cause inflation. But despite inflation, cash is still very useful, and there always remains a price at which someone will surrender their T-bill to the Fed in exchange for new Federal Reserve deposits.

As for how we came to be in a position of using those particular pieces of paper (Federal Reserve notes) as our medium of exchange, you might be interested in this quick monetary history of the United States from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Very briefly, the notes were originally gold certificates, which you could exchange for physical gold if you wanted. That convertibility was suspended in the 1930s, though when I was a boy the notes were still labeled at the top as “silver certificates”, meaning you could if you wanted convert them into 4 silver quarters or 10 silver dimes. Inflation caused the price of silver to climb to a point where 4 silver quarters were much to be preferred to one paper dollar, at which point the notes received their current designation as Federal Reserve notes. But at this point, their acceptance as a medium of exchange was sufficiently well established that their value could be derived solely from that social benefit of having some agreed-upon medium of exchange.

Prof. Hamilton ends his discussion with some specific suggestions for how the Fed and

treasury could behave differently which, in his opinion, would avoid some likely future problems.

I hope the officials involved will read his recommendations and the discussion that ensued.

The actions under discussion were all taken on an emergency basis, to respond to some real problems. In one sense, the intervention worked. The succession of failed firms stopped. Trading in the short term commercial market continues.

Should the Fed be content with the current level of credit availability? Is this the end of major changes in the Fed balance sheet? Since most of these changes occurred before the Bailout money became available, perhaps the situation has stabilized enough so that the Congress should claw back the $350 billion not yet spent.

JDH,

You say

1) “The first such device was to reach an agreement with the Treasury for the Treasury to simply hold on to a huge volume of Federal Reserve deposits”

then

2) “The second measure that the Fed employed to allow this ballooning of its assets was to start paying banks an interest rate on reserves that is exactly equal to its target for the fed funds rate itself, essentially eliminating any incentive for the banks to lend fed funds and encouraging banks instead to simply let excess reserves accumulate.”

But, that chronology doesn’t match with actual Fed balancesheet reports.

1) Bank reserves were rising before the deal between the fed and the Treasury about Supplementary Financing Account.

The Treasury Supplementary Financing program was annonced on september, 17. This new entry was created in Fed BS of September 25 release. ( http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/20080925/)

But in this release, Depository institution reserve account was already at 95.301 millions.

Long term bank reserves seems to be arount 20 billions. I cannot find a graphic on St Louis Research website which give consistant values with the values found in FED H41.

In fact, banks reserves was already rising since the begining of september. ( http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/20080904/ ) with a spike during July.

2) Bank reserves were rising before the Fed start to pay interest on it.

The payement of interests on bank reserve was annonced on October, 6.http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20081006a.htm

But on the Fed BS statement released just before this annoucement, bank reserves were already at 179.291 millions. ( http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/20081002/ )

Here is a slightly different take from a non-economist. The mechanics of what the Fed and Treasury are doing seem, to me, irrelevant. Mathematically a teacup with handle and and a nut or washer are topologically equivalent as the hole in each defines each structure. A perfect metal worker could transform a nut into a metal teacup by redistributing the metal creating no new holes. By analogy the Fed and the Treasury and all of their equivalents over the world could be replaced by a single guy with a spreadsheet. Any value could be placed in any cell and as long as he was able to apportion new credits to the productive to account for the growth of productivity no one would care what value was in what cell. What would be observed would be a constant interest rate that would exactly be the sum of time value of money and the cost of providing the lending. The implication that Fed and Treasury are different seems to me nonsensical and we are left only with the not so vague foreboding that the money supply is not being controlled and has never been controlled just like the debt no matter what rationale is presented. Merry Christmas.

Would someone explain how the money supply will be increased and an inflation rate of 3% is achieved (good luck). The banks aren’t going to loan so the normal avenue of bank pyramiding won’t work. It seems the Fed or banks would have to buy bonds with created money from the treasury and or the Fed pruchase a lot more assets at a greater rate than money being retired from loan pay offs as banks recapitalize. Any other avenues?

CJ:

I admit that I don’t quite follow your confusion but I get enough of your analogy to the concept of equivalence in math to at least posit a foundational discrepancy. The fact that you can go from a cup to a washer with a series of translations ignores the fact that specific points the lie on the cup may instead lie outside the washer once the transformation process is complete; or you can look at it as those points are being moved somewhere else against their will by external forces (your metal worker). The impact of those external forces should not be ignored when dealing with forces that affect human societies.