The Federal Reserve can’t be entirely pleased with markets’ reaction to its announcement on Wednesday of quantitative goals for purchases of long-term assets.

The Fed’s objective in this quantitative easing is to move the inflation rate back into positive territory. Let’s begin by reviewing the new consumer price index data that were also released on Wednesday by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. These numbers show further modest movement away from a deflationary tendency prior to any actions by the Fed. The seasonally adjusted February CPI was 0.4% higher than in January, which would be a 4.8% annual inflation rate if sustained for a year. Although that’s plenty for one month, it nevertheless is still substantially smaller in absolute value than the drops seen in October through December.

|

That leaves the seasonally unadjusted CPI just 0.2% above its value from February 2008.

|

If we leave out food and energy, the February increase (+0.2% monthly) implies an annual inflation rate of 2.4%,

|

and the year-over-year core inflation rate now stands at 1.8%. Both of these last two numbers are a bit below what I think the Fed should want to see, but they continue to offer comfort that we had been moving away from the deflation threat before the Fed’s announcement.

|

In discussing the Fed’s announcement of its plan for quantitative easing, I wrote:

What will be the indication that we’ve done all we can with this tool? I would urge the Fed to be watching the exchange rate and commodity prices quite closely for an indication that the deflation tide has turned.

|

| aluminum | +6.4 |

| coffee | +6.8 |

| copper | +4.1 |

| corn | +3.9 |

| cotton | +3.2 |

| gold | +4.0 |

| lead | -1.7 |

| silver | +6.3 |

| tin | -0.4 |

| wheat | -0.4 |

| zinc | +0.3 |

| crude oil | +3.9 |

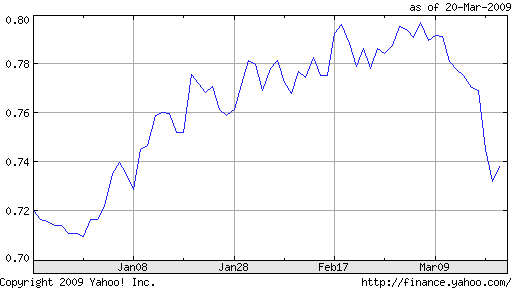

That’s why I doubt the Fed was pleased to see the dollar fall 5% against the euro last week. The Fed wanted everybody to wake up and notice that deflation is no longer on the table, but it’s another thing if markets run off in the other direction fearful that a major inflation is coming. Notwithstanding, the dollar’s move at the end of the week only served to undo an appreciation over the first part of the year, an appreciation that may have been unwelcome and unwarranted.

Prices of a number of commodities also zipped up about 5% on the news. Again this is a disturbing development, but again it still leaves the prices of many commodities below where they started the year, as the graph below demonstrates.

|

Commodity prices are quite sensitive to the level of real economic activity. If we had been about to repeat a global Great Depression with attendant significant U.S. deflation, maybe $35 oil could be justified. And if the Fed has now successfully communicated that’s not going to happen, a commodities rebound might be quite appropriate.

But I think we also have to worry about whether this might be the start of a replay of what we saw a year ago, when excessively expansionary Fed policy provided fuel for commodity price speculation. In January of this year, Fed Chair Ben Bernanke offered this ex post appraisal of the Fed’s policy in early 2008:

The [FOMC’s] aggressive monetary easing was not without risks. During the early phase of rate reductions, some observers expressed concern that these policy actions would stoke inflation. These concerns intensified as inflation reached high levels in mid-2008, mostly reflecting a surge in the prices of oil and other commodities. The Committee takes its responsibility to ensure price stability extremely seriously, and throughout this period it remained closely attuned to developments in inflation and inflation expectations. However, the Committee also maintained the view that the rapid rise in commodity prices in 2008 primarily reflected sharply increased demand for raw materials in emerging market economies, in combination with constraints on the supply of these materials, rather than general inflationary pressures. Committee members expected that, at some point, global economic growth would moderate, resulting in slower increases in the demand for commodities and a leveling out in their prices–as reflected, for example, in the pattern of futures market prices. As you know, commodity prices peaked during the summer and, rather than leveling out, have actually fallen dramatically with the weakening in global economic activity. As a consequence, overall inflation has already declined significantly and appears likely to moderate further.

Bernanke seemed here to be taking the position that since the Fed got the long run correct– the end of 2008 brought strong disinflationary pressures and commodity prices collapsed– it was OK to ignore the commodity price boom of early 2008. I disagree with that assessment. In my opinion, the oil price increase of 2008:H1 was highly destabilizing for the economy and a key factor that turned an economic slowdown into a recession. One of the lessons for monetary policy that we should draw from the recent behavior of real estate and commodity prices is that the Fed can’t ignore the consequences of its actions for speculative prices, even if (or perhaps, particularly if) that speculation reflects a basic misreading of fundamentals. If commodity speculators are erroneously about to declare the bull game is back, that in my mind would be a development that would require the Fed to scale back its plans for quantitative easing.

How would I handle that in practice? I think the best strategy is for the Fed to lay all its cards on the table face up, telling everybody exactly what it is hoping to achieve and how it is going to do it. The Fed needs to communicate that it’s not going to allow the price level to fall, but it’s also not going to allow runaway commodity prices. So why not announce a specific target of, say, 2-3% for headline inflation, which implies a direct commitment that the Fed will become more cautious if it observes a response to its actions of items such as oil and food? This could be accompanied by statements from Fed officials along the lines that they’re watching commodity markets and exchange rates closely for an indication that quantitative easing has accomplished all it set out to do.

All this requires acknowledging from the outset that there is only so much the Fed can accomplish in this situation, a premise that in my mind has considerable merit. But in order to be able to contribute whatever it can, the Fed must be able to speak with clarity and credibility.

If the moves we saw in exchange rates and commodity prices this week are the end of the story, then I think all is well. But if they are the beginning of a new trend, the Fed will need to react.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

economics,

Federal Reserve,

deflation,

inflation

Sage advice. Balanced and responsive to reality. How do people get appointed to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Board? Any selected independent of the head of the Regional banks? Can members of the Board maintain a Blog?

“If the moves we saw in exchange rates and commodity prices this week are the end of the story, then I think all is well.”

All is well for whom?

Ron: By “all is well” I mean stick with the current plan of quantitative easing.

Reformer Ray: Governors are nominated by the U.S. President and confirmed by the Senate. Presidents of individual Federal Reserve Banks, who have rotating votes on the FOMC, are selected by the board of directors of the individual bank.

No explicit inflation targeting framework? After years and years of talk and talk and all these rumours and second-guessing?

And now it looks like the fed is acting in panic mode? If the market responds like the fed doesn’t really have a good handle on the situation, should fed watchers be surprised?

To quibble, I believe that oil prices could decline much lower than US$35/b in real terms with or without any “deflation”. There is more real economic contraction to come and OPEC is building forward capacity. (There in lies the supreme irony of actual OPEC quota reductions.)

It’s really too bad, because the weaker petroleum prices will encourage many in the USA to continue to support dysfunctional national energy policies and hegemony-destroying foreign policy particularly but not exclusively in regards to the Middle East.

I agree wholeheartedly that getting the fed to “lay all the cards out” would help enormously. It is simply too bad that fundamental mandate reform seems to be off the table.

JDH says: Bernanke seemed here to be taking the position that since the Fed got the long run correct– the end of 2008 brought strong disinflationary pressures and commodity prices collapsed– it was OK to ignore the commodity price boom of early 2008. I disagree with that assessment. In my opinion, the oil price increase of 2008:H1 was highly destabilizing for the economy and a key factor that turned an economic slowdown into a recession.

A few things here. First, I think it is outside the realm of monetary policy (the Fed’s home base) to take responsibility for excess demand as a result of speculation and genuine buying. As Bernanke said, there were very real global growth and/or stockpiling forces at work driving up commodity prices. That short run “inflation” was not “real” in the monetary sense though — it squeezed disposable incomes enough to solve itself. That is indicative that there was no real sustainable inflation — wages didn’t budge. Now if wages were moving up rapidly to support increased spending on the rare fuel, that would be the sign of a monetary phenomenon.

Now a QE policy is a different story. Exchange rate overshoot is built into the short run models when money supply increases are projected without corresponding output increases. Furthermore, the markets aren’t yet convinced on what the EU will do yet (I can’t empirically support this, but look at the surprise move in gold and the long end of our treasury curve. Most of the market was not expecting QE out of the Fed despite the SNB and BOE already embarking on the path. The 30 yr would not have moved up almost 8% at one point if it were baked in). I don’t think the Fed would be disappointed with a 5% weakening of the dollar index – it was probably in their models. So I don’t think the short term move is a meaningful signal towards inflation targeting. That said, these commodity price moves are somewhat a function of the structure of the global economies and government policy (and physical constraints) towards the production and laws towards speculation of those commodities. I emailed you an example plan where government policy dictates 200 breeder nuke plants (and/or on-facility reprocessing exists) are built, a trillion or two in stimulus is spent to mandate electric cars are a primary transport, and wanted to hear back your ideas. The idea being that if energy supply was never a problem, energy prices would not be a destination for speculation. Excess supply and increased productivity yielded from this advance in technology would give us a license to print, at least enough to set the broad price level high enough to prop up real estate to the point of returning bank balance sheets back to slightly above water levels.

Investors who hold US bonds are not going to sit idly by while the Fed and Treasury engage in actions that reduce the value of their holdings. Instead they will actively and immediately hedge their positions with commodities regardless of the level of economic activity or the value of the commodities. THAT is what got us into the mess we are in today: TOO LOOSE monetary policy resulting is commodities priced above and beyond what Americans can afford. The only way to rectify this situation is by allowing prices of goods, services, and commodities to fall such that they are affordable again. Unleashing loads of printed money won’t do anyone any good. Banks are hoarding money for a reason.

All the changes in the CPI you are making a big deal of are due to energy. If you take out energy the CPI continues to show inflation moderating.

monthly change in

cpi excl energy

cpi

Jan-08 0.3

Feb-08 0.1

Mar-08 0.2

Apr-08 0.2

May-08 0.2

Jun-08 0.3

Jul-08 0.4

Aug-08 0.2

Sep-08 0.2

Oct-08 0.1

Nov-08 0.1

Dec-08 0.0

Jan-09 0.2

Feb-09 0.1

Essentially we have five straight months where the cpi excluding energy rose 0.1%.

The commodities you are charting show half of the commodities up since the start of the year and half down — essentially statistical noise.

On Friday the CRB index of industrial raw materials was 328.9 as compared to 329.5 at year end and a local peak of 346.0 on 9 February.

For the last several months oil has been trading in a narrow range after falling from near $150 to $30 in December. The rise in the inflation rate is just a random movement of oil in a cobweb function since its December bottom.

Moreover, one of the best leading indices of commodity prices , the Dry Ships Index is starting to roll over.

I see absolutely no evidence of the pick up in inflation you are reporting.

The commodities bull game will come back only if chinese people keep spending more and more. So the FED should react to a chinese demand-shock ?

I truly appreciate the humility of this post. Too many Keynsians assume a degree of control that is unwarranted by the empirical evidence. In the final analysis individuals make choices.

Wait, I am confused.

ABout 10 days ago, JDH said that deflation was a worry, and that 3% inflation should be the target.

Now that CPI has risen and commodities have risen, isn’t this what JDH wanted?

If monetary policy is too loose, as soon as the economy starts to recover, the Fed can slowly tick up rates by 25 bps each session, getting them up to 2.5% or so.

So where is the problem?

GK: If this is all that happens, there is no problem. But if this is the beginning of a new trend, the Fed will need to react.

“So why not announce a specific target of, say, 2-3% for headline inflation…”

That is a good question. Why wouldn’t the FED announce a inflation target. Didn’t Bernanke specifically recommend that Japan set an inflation target in the late 1990s. So why not one for the FED?

My guess is the FED isn’t really worried about deflation. Price inflation the past two months have been anything but negative. CPI was up 0.7% and PPI was up 0.9%. Monetary inflation has also been going up. The past 3 months MZM is up 20.7% and M2 is up 15.2%.

The FED is worried about asset deflation and is trying mightily to put a floor under asset prices. The last thing they want to see is inflation expectations surging.

An inflation target right now would undermine those efforts and make holding down longer term rates harder. A 2-3% inflation target would imply nominal rates would need to go up to 3.8% just to avoid negative real returns.

Tiny Tim Geithner and Helicopter Ben Bernanke are going to ruin this country. They both need to GO!

http://fargoneworld.blogspot.com

If the Fed “laid all their cards on the table” they could easily be graded on how well they are doing in reaching their goal. Or how poorly they are doing, of course. Not likely to happen…

You said,”I think the best strategy is for the Fed to lay all its cards on the table face up, telling everybody exactly what it is hoping to achieve and how it is going to do it.”

Exactly right, and the same applies to Treasury re fiscal policy. Americans generally no longer trust either the Fed or Treasury to do the right thing, both because they have done so much wrong and because they have been unwilling to be transparent about their goals, processes, and plans.

Without transparency–and hopefully acceptance–we can not succeed.

One of the few “good things” about Helicopter Ben’s extended cash-for-trash programs–TALF is to be extended to legacy asset classes, not just new originations as had been proposed–is that it credibly addresses the debt-deflation spiral risk–for which there is no cure–by generating an irreversible monetary base increase to fuel some well-justified expectations of subsequent inflation. Of course, the danger of this irreversibility, especially on a scale this large, is that commercial banks will no longer hoard their excess reserves upon economic recovery, popping M2 to generate a quite large inflationary spiral. Markets do not yet seem concerned over this possibility, perhaps because of the immediate debt-deflation spiral spectre from the current and forseeable deleveraging.

Normally an oil shock is followed by several years of transportation innovation. Intead we have automobile companies going to government to protect their old bets.

thats an interesting view about the facts behind QA, and all friends working on that :

http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/story/26793903/the_big_takeover

->Gosh, the buddy who wrote that seems to be an insider.

Professor,

Once again you present an excellent post.

I am concerned that the ink is just drying on the FED actions and you have changed your stance from inflation to caution – though I totally agree with you it was a rather quick change.

You wrote:

In my opinion, the oil price increase of 2008:H1 was highly destabilizing for the economy and a key factor that turned an economic slowdown into a recession.

Once again I agree but the price of oil is simply an indicator of a deeper problem. The deflation of the late 1990s seriously hurt oil production infrastructure such that the boom after 2000 was more than oil producers could handle. The problem is that oil prices spiked then fell at such a quick rate that the oil producers had no chance to correct the problems of insufficient storage, drilling, and production equipment.

The price of oil is strongly influenced by inflation such that it is a leading commodity. It will probably lead the next inflationary boom and this will, as you say, will be “highly destabilizing” for any recovery.

Recognizing that any actions by the FED take from 6 months to 18 months to become manifest in the economy the recent pledge by Bernanke of $1 trillion will impact inflation around the end of 2010 to 2011. With the moves in commodities this could be right at the point when inflation really sends prices up. That would mean a double punch to inflation.

I expect low real growth, high unemployment, with soaring inflation, the condition Keynes never believed could exist, stagflation. So I have change my name for the current period. I now call it the Great Stagflationary Depression.

What if the current value of the dollar was half what it is now if all currencies were allowed to float in value? In this case, imported commodities such as oil should be about double what they are now. I suspect the Fed’s QE policies have as much to do with forced devaluation of the dollar as it is to do with extinguishing deflationary expectations.

Doc wrote:

policies have as much to do with forced devaluation of the dollar as it is to do with extinguishing deflationary expectations.

Doc,

What’s the difference?

DickF, I meant to highlight the difference in the stated intentions and goals of the Fed despite the result being functionally equivalent in much the same way as you point out. One of the Fed’s goals is price stability, but I think their actions have more to do with trade (in this case) and indirectly their related goal of employment. Successfully weakening the dollar substantially should strengthen exports and employment. The rub of course, is the income sapping effect of expensive imported necessities such as oil. However, that would provide the rationale and incentives to develop alternate energy sources. This also should bolster conventional domestic energy investment.

Galbraith on PPPIG…

http://finance.yahoo.com/tech-ticker/article/216311/Part-I-Geithner's-Plan-%22Extremely-Dangerous%22-Economist-Galbraith-Says?tickers=%5Egspc,%5Edji,c,bac,jpm,WFC?sec=topStories&pos=2&asset=TBD&ccode=TBD

Are you out of your mind? The Fed got us in this mess by its its inflationary policies and encouragement of reckless speculation and you encourage it to destroy the purchasing power of the currency?

First, if the methodology had remained the same as it was in the 1970s, the reported the inflation rate over the past 20 years would have been much higher. Second, inflation is bad because it robs workers of purchasing power and creates unsustainable distortions in the economy and encourages consumption over savings. Third, it prevents workers and savers from joying all of the benefits that productivity driven falling prices would bring.

Whether you like it or not we are in a commodity bull market. And while I still expect a wash out if demand collapses over the short term the lack of adequate investment due to a twenty year commodity bear market that only ended around eight years ago means that the supply side dangers are grave. In a JIT world disruptions present a major risk to the real economy and we could easily see production lines idled because suppliers are unable to deliver simple items because the specialty materials that are needed to make them are in short supply.

Imagine what happens if the reduction of base metals mining activity causes the inventory of silver that is needed for electronic switches to fall to less than a few days of use. While users could easily bid the price up to $50 an ounce or more without impacting the cost of the end product by much (because so little is used) it would not help them get enough supply into the market to prevent production disruptions.

Or imagine what happens when investors (and more importantly producers) figure out that the peak production of light sweet crude is already three years in the past and that the growth in NGLs and unconventional production will be unable to meet the growth of future demand. Or what the collapse of of natural gas prices and the closure of horizontal wells in the shale areas will mean to future supply for the US? Or what happens if the present trend at Cantarell means to American refineries and imports from Mexico.

The bottom line is that there is a real economy that requires real actions by serious people who are willing to risk their capital to make a buck. Having the Fed intervene by printing more fiat paper does not help us solve any of those real problems. All it will do is create further distortions that will draw scarce resources into speculative activities that would never be supported by a the free market.

You go and keep assuming that the Fed can help and I will try to get rich by betting on the inability of central planners to run the economy. In a few years the passage of time will tell us who was right.

Vangel, the Fed is doing QE to prevent a debt deflationary spiral through a dollar devaluation. The dollar’s value is excessively high due to China and other countries artificially pegging the value of their currencies to it. I don’t think the Fed’s way of solving this issue is the best one. I would rather see the use of import certificates or some other method. But, the Fed is pursuing this policy nevertheless and it will result in the debt getting inflated away IMO.

Well, with the stock market up 7% today, at least it looks like the markets are happy enough with the Geithner Plan, on first impression.

Doc, that is exactly what the Fed is trying to do; to inflate the debt away and reduce the NPV of the SS and Medicare promises made by the government to American citizens. Of course, a USD devaluation will eventually lead to a much lower standard of living as foreigners are able to bid up the price of scarce resources to the point where Americans cannot afford to buy as many goods as they used to. So far nobody has explained why it is moral to force prudent citizens to pay for the reckless actions of others.

Doc: “but I think their actions have more to do with trade (in this case) and indirectly their related goal of employment. Successfully weakening the dollar substantially should strengthen exports and employment.”

You may be right, but it would be a very shortsighted policy. A fall in the dollar against the euro will bring the yuan down against the euro as well. The euro area is simply not big enough to support these two economies by stimulus through improved trade balance. Instead, the euro area will suffer and the euro may crack. We may also see some serious protectionist pressures in Europe against the Asian currency interventions.

Prof: You nearly seem to be arguing that loose monetary policy increases commodity prices which, as you correctly point out, are deflationary. Therefore loose monetary policy is deflationary! Of course you don’t actually argue this but I think the paradox calls into question the vogue for (high >2%) inflation targeting.

Let’s start with a simple 2-equation version of Krugman’s model which illustrates the deflation spiral. Krugman describes a series of more complex models, but I hope that my synopsis captures the essence of his and your ideas. The first equation is an expectations-augmented Phillips curve, which just says that inflation is positively related to expected inflation and to activity. The second equation says that activity is negatively related to the real (i.e nominal less expected inflation) rate.

In this model, inflation expectations are like pixie-dust – if only we all believe hard enough, then it will come true. A belief in higher inflation lowers the real interest rate, which stimulates activity which eventually leads to the inflation you believed in. The second barrel to this argument rests on the assumption that realized inflation is a function of expected inflation (not past inflation) and activity. So raising inflation expectations raises the base for inflation and also raises activity. Call it the base effect and the real rate effect. This simple model not only explains the deflation trap, but also promises a path to deliverance – convince people to believe in inflation.

The problem with this approach is that it involves two drastic simplifications that crucially misrepresent a modern economy. The model’s financial sector consists only of a short term nominal bond whose price does not respond to expected inflation; it’s nominal rate remains stuck at zero. So the financial side of this model economy is immune to inflation expectations (at least at points of interest near the liquidity trap.) The goods sector of this model however responds dramatically to inflation expectations via the real rate effect and via the base effect on inflation.

Now in practice the opposite is closer to the truth; in a modern economy, the financial sector is more responsive to changes in inflation expectations than the goods sector is. When inflation expectations rise, the first and most dominant effect is that the yield on longer term government bonds rise. This relation is one of the strongest and clearest empirical relations in financial economics. As well commodity prices may rise (they hedge future inflation) and the exchange rate may depreciate (or not). The effect of inflation on the whole financial sector is not well approximated by the number zero which is the assumption the Krugman model makes.

And, in contrast to the model economy, there is little empirical evidence that the goods sector of the economy is strongly stimulated by expected inflation. In the model, spending on goods is determined (negatively) by the short term real rate of interest. This assumption is simple and convenient, and can be given rigorous micro-foundations for both investment and consumption spending: changes in short term real rates change the cost of capital and therefore affect expenditure on durable consumer and investment goods, and consumers respond to higher real rates by deferring current consumption in favour of future consumption.

But Bernanke and Gertler (1995) point out the empirical evidence simply does not support the cost-of-capital story. And empirical studies on aggregate consumption consistently find that consumers’ willingness to defer consumption in response to higher real rates (the elasticity of intertemporal substitution of consumption) is essentially zero. Instead cashflow and balance sheet effects seem to explain spending behaviour better than cost of capital effects. And cashflow and balance sheet effects are best thought of in terms of nominal interest rates.

The base effect (of expected inflation on future realized inflation) is on equally shaky ground. Robert Gordon (2008) in a survey covering 50 years of theoretical and empirical work on US inflation finds little role for inflation expectations in the post-war US experience. Future inflation is related to past inflation – the relation is one of simple inertia, not of expectations. Makes sense to me for most goods (not financial assets or commodities though).

This analysis suggests the Krugman/Hamilton argument for promising future inflation is flawed on two counts. First, such a policy will not increase current spending but 2) it will raise nominal interest rates, and will probably raise commodity prices as well. The balance sheets of financial intermediaries will become further impaired and the overall effect will clearly be contractionary. The contraction in the goods sector would cause prices to fall thus contributing to deflation. Thus a promise to increase future inflation is not dynamically consistent so such a promise would undermine the credibility of the central bank.

If the central banks are going to clearly announce what they are going to do and why, then they need to have a plausible model of the economy, and I do not think the pixie-dust theory of deflation prevention is plausible.

James, you write:

But I agree with Nobel Prize winning economist Paul Krugman that the evidence isn’t there that speculators caused that increase in commodity prices. In Krugman’s words:

and

It appears that the run up in oil and other commodities was due to fundamentals, not speculation, and we certainly don’t want to cut oil and other commodity prices by decreasing demand through prolonging the recession, cutting employment, production, and wealth. The cure is worse than the disease.

It’s better to let those prices run up from ending the recession, and having that be an impetus for conservation, recycling, and increased investment in the basic science and technologies to do those things better. The sun provides all the energy we’ll ever need for billions of years; we just need to invest the money in the science that will allow us to harvest it cheaply. Likewise, no commodities ever leave the planet; gravity is too strong (except for the occasional space launch). We just need to invest in the technology to recycle them faster and better, and mine more than just the very shallow tiny surface of our globe.

Richard H. Serlin: You make some very good points. JDH’s exact wording above aside, I believe that JDH largely agrees with Krugman on the relative unimportance of speculation in commodity markets if I understood what he has written on the subject in the past.

Commodity prices were not in a speculative bubble but they certaintly appear to have overshot long-term fundamental values in H108 given the co-ordination crisis the global economy was experiencing.

The past does not allow one to predict the future but does provide information on the range of possibilities. To the best of my knowledge, every oil/commodity price shock in the post-war period has been followed by a recession. The bull markets in commodities take several years to fully unwind.

What we are currently observing could very well be a bear market rally in both commodity prices and equity values.

If the equity markets are “correct”, then the US economy is bottoming and turning around by September 2009. I strongly doubt that.

Old-school Keynesian,

Interesting argument. Increasing prices in deflation, hummmm.

So if I understand your logic, a situation where there are two apples and you and I have one dollar each, if I can get you to believe that we are in an inflation pixie-dust will suddenly produce more than two apples. Hummm.

My guess is that JDH’s arguments fall in line with Krugman’s hypothesis that oil producers under these conditions may neglect maintenance and expansion of capacity, and instead invest revenues from price increases in markets abroad, like real estate back securities. i.e., betting that others won’t expand capacity, move to alternatives, and/or demand won’t collapse; that prices will always go up. Investing by keeping it in the ground.

See Krugman’s article on OPEC and multiple equilibria from 2001.

A fools game, but in a world with no shortage of fools.

Kurgman on Energy Crises and Multiple Equilibria

Let’s assume the Fed’s faces losses on its lower quality assets if it tries to fully unwind its recent ‘ballooney’ activity in an effort to forestall inflation. Can anyone tell me why the Fed can’t just use the first textbook means it has of controlling the monetary base, namely adjusting reserve requirements? Just increase them.

Of course, that still leaves the lower quality assets on its balance sheet. But in the meantime, let the Fed and Treasury estimate what increase in taxes on inherited wealth, high incomes, and corporate profits would be needed to make up the loss on those assets if sold on the open market and then levy the said tax increases.

I.e., act like America is a nation of mostly non-delusional, non-moronic adults governed by mostly non-corrupt, non-intellectually dishonest political leaders for a change.

Oh wait. I think I’ve spotted major flaws in my otherwise cunning plan…