The U.S. economy continues to recover at a painfully slow pace.

December auto sales looked reasonably good, at least when you compare them with the numbers we’ve been seeing over the last 15 months. Apart from the cash-for-clunkers August 2009 outlier, seasonally unadjusted U.S. car sales in December were higher than any month since the Lehman failure in September 2008. Even so, that still leaves December 2009 30% below the average December over 2004-2007. The worst may be behind us, but we’re still a long way from normal.

|

But without question Friday’s report that seasonally adjusted U.S. payrolls declined by another 85,000 workers in December was a disappointment. I recall that when President Obama was asked on February 9, “how can the American people gauge whether or not your programs are working?”,

he responded:

I think my initial measure of success is creating or saving 4 million jobs. That’s bottom line No. 1, because if people are working, then they’ve got enough confidence to make purchases, to make investments. Businesses start seeing that consumers are out there with a little more confidence, and they start making investments, which means they start hiring workers. So step No. 1, job creation.

With Friday’s numbers, total U.S. employment has now fallen by over 4.1 million jobs, from 135.1 million Americans working in December 2008 to 130.9 million a million last month. That’s a bigger loss (by about a million workers) than was seen in any other 12-month interval between 1939 and 2008.

If you’d hoped that growth in employment had finally begun, Friday’s numbers were rudely disappointing. But if you instead had been seeing an anemic recovery not yet strong enough to bring employment up with it, this week’s news says that’s still about where things stand.

Andrew Samwick and Phil Izzo survey some of the different responses to the employment report. I think Donald Marron had the right perspective:

job losses averaged 69,000 per month in the last quarter of 2009. That’s unwelcome, but much better than the average of 691,000 jobs lost in each of the first three months of the year.

Rather than a robust V, the recovery seems to be held back by ongoing deleveraging by consumers and the institutions that would lend to them. If that continues, we might expect to see continuing output growth in 2010 that eventually starts to bring employment back up, though it may be a long time before employment levels return to those achieved in 2008.

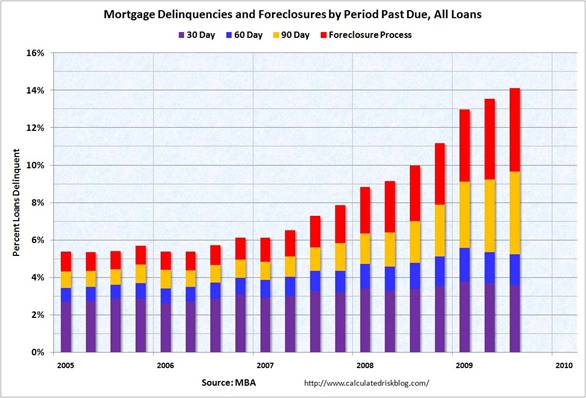

As long as the status quo continues, the recovery still has a lot of fragility. As the president observed, job losses themselves contribute an unfavorable dynamic to spending and bankruptcies, and there are a lot of mortgage delinquencies that have not yet reached the foreclosure stage. I do not rule out the potential for another round of concerns about the solvency of key institutions as those developments play out.

|

So yes, the situation continues to improve, but no, it’s not anywhere near where we’d like it to be.

Yes, I think you sum up the situation about right.

JDH: “the recovery seems to be held back by ongoing deleveraging by consumers and the institutions that would lend to them.”

I don’t suppose those institutions spending billions of dollars on bonuses is doing much to help their deleveraging.

http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf (P22)

The breakdown of the unemployed by industry is more worrying,as the industrial sectors are having the highest records of unemployed in term of flows and stocks.

As long as this trend is not reversed the economies will remain suspicious and their financial the same.

Here we have a patient who has been bleeding profusely. Now as his life is ebbing away his bleeding begins to slow and the doctors say, “Sure he is still bleeding but not as much as when he was first wounded.”

The economy is seriously wounded. Viable companies have let as many go as they can and still stay in business, but declines in business are forcing them to take even greater cuts. A loss of 69,000 jobs today may be worse than a loss of 691,000 last year.

The patient is sick but the doctors continue to bleed him.

The graph of mortgage delinquencies is striking. Does anyone have any idea what percent of the MBS has been vacuumed up by the Fed? If the Fed stops buying these in March what happens then?

Very good BT…well, they extend that March deadline and modify the clunker program.

Ricardo also makes an excellent point–about job losses today and job losses a year ago. Now if he could only forget the leeches.

Dear Professor,

I have been reading The Return of Depression Economics by Mr. Krugman and was intrigued by his belief that a policy of expected inflation may have succeeded in getting Japan out of its liquidity trap during the 1990s. I believe the gist of his argument was that by increasing inflation, the real value of money will increase in the future, so people will be discouraged from holding money propping up consumer spending.

At this time in America when we are essentially in a liquidity trap where monetary policy is frivolous, and public spending is running out of steam, would the same policy of expected inflation work to speed up recovery?

The only caveat I can see with inflation at this point is that a series of inflationary policies will push up interest rates in the future which would hurt banks balance sheets and cause more stress on banks.

Could you (or fellow readers) please shed some light on this matter?

Qayam Jetha –

I would beg to differ, Japan is still in its liquidity trap and has been joined by the United States. Japan has been in a recession for the last 20 years with extremely low interest rates for most of that period. Japan, finding that 0% interest rates would not stimulate the economy, embarked on QUATITATIVE EASING (QE) from March 2001 until March 2006, increasing the BOJ reserves from 5 to 35 Trillion Yen… with little effect. Japan still has a recessionary and deflationary economy.

I believe that Japan illustrates that low central bank interest rates and QE have little impact on advanced economies in recession. In addition, it’s questionable whether the FED can continue QE (inflationary policy) with the large US government deficit.

QE and low interest rates are intended (from the government’s perspective) to make business investment easier, by making funds and a higher interest spread available to commercial banks. What really happens is that commercial banks demand more collateral and are more descriminating during a recession, reducing the money loaned to consumers and small businesses. In America, QE has resulted in support of the stock markets. American banks have joined Japan and Switzerland as places for carry-trade operations on foreign securities.

From my perspective, QE operations are essentially mercantilist… The objectives are to- reduce the foreign exchange value of a currency so that the county is more competative in international markets.

- Inject lots of money into tier 1 banks so that they can avoid bankruptcy along with their best customers- private equity and hedge funds.

Your caveat about higher future interest rates hurting banks balance sheets, depends on the bank. By securitizing their loans, large sophisticated banks can off-load their long-term liabilities. Its the smaller community banks that will be smashed if they hold on to long-term loans or bonds.

In my previous post I made a typo and it should read “. . .the real value of money will decrease in the future.”

Mark – Thanks for the response and the insight. I suppose that I may need clarification on the differences (if any) between quantitative easing and government spending. It seems like the end result of both policies are the same – getting money out into the economy to reap the benefit of the multiplier – but does quantitative easing add to the budget deficit?

I also did not realize that Japan implemented quantitative easing altogether and that it proved ineffective. From what we I recall having learned last year in class, the IS-LM model shows that during a liquidity trap monetary policy is completely useless (obviously) but fiscal policy is completely effective since it doesn’t crowd out investment spending. Is there any reason as to why the quantitative easing/gov’t spending has proven ineffective in Japan’s case, or is that the million dollar question?

I appreciated the insight on how quantitative easing is mercantilist. I didn’t realize that a fundamental goal of easing is to make exports more competitive. I just thought it was a further means to increase the money supply.

Calmo,

Leeches = politicians

Blood-sucking = deficits that lead to taxation

(directly or through inflation – I would include borrowing but there is not enough money in the world for us to borrow to solve our debt problem)

Qayam Jetha-

The fundamental difference between QE and government spending are:

– Government Spending issues bonds that place a drag on the economy via the interest that has to be serviced. Theoretically, government spending involves democratic consensus of the purchase of needed goods or services.

– Quantitative Easing issues no bonds, the new reserves are injected directly into the banking system, sometimes with the fig leaf of an asset purchase. There is no democratic consensus, the action is taken by command of the central bank with consent of the president. No goods or services are purchased, only dilution of existing currency, and support of impaired securities is achieved.

I think the traditional source of job creation by laid off workers investing and starting their own businesses has been severely depressed by the negative government policy direction and the disencentives it produces.

Let’s see, if I am laid off and have $100,000. Do I take the risk to start a business? Looking out a year or two what do I see:

1. My tax rate going up next year

2. Potential higher energy costs

3. Mandated heathcare costs

4. Increased unemployment tax rates

5. Increased minimum wage rate

6. Removal of social security tax cap

7. New banking regulations (increased reserves, mark to market asset write downs) which result in less credit

8. Taxes on investments/trades

9. Unknown validity of contracts due to cram downs, etc.

10. Sarbanes compliance costs

11. And a host of other new regulations, license requirements to generate more govt. income.

12. If I end up beating the odds and become successful the govt will take most of business withthe inheritence tax.

Obviously entreprenuarial and small business expansion cash is sitting on the sidelines. Large companies on the other hand can avoid costs because of their size and global nature (just hire and produce offshore). I’m curious if anyone has seen any comparisons between prior recessions showing small and large business job creation?