Domestic Impacts and Cross-Border Impacts Contrasted

There seems to be a tendency in recent studies to place ascribe greater impact to forward guidance than to quantitative measures, such as purchases of Treasurys and MBSs — at least insofar as domestic interest rates are concerned. [1] [2] But it’s interesting just because asset purchases don’t necessarily affect interest rates, it doesn’t follow that exchange rates and other cross-border asset prices, would be similarly unaffected by quantitative/credit easing measures.

Consider this statement from Steven Englander of Citi (8/30, not online):

Investors globally are taking the prospect of Fed tapering and the end of QE as a signal that global liquidity is being withdrawn. If the Fed is correct that policy is not being tightened, the reaction in G10 and EM FX high beta currencies is not justified. We think investors are correct in being skeptical that forward guidance represents a concrete policy commitment upon which they should act.

…

At Jackson Hole, the MPC’s Charles Bean and ECB’s Frank made the case that forward guidance clarified but did not change their central banks’ underlying policies. This is the short version of why forward guidance is less powerful than QE.

For the academics among you, consider the following challenge. Write down a model of central bank behavior that runs off an economic forecast and a policy rule (for example, a Taylor rule). Now write down a model that embeds forward guidance. How different are they? If they are not very different than forward guidance is probably giving you a second order impact at best versus the ancien regime of forecast + Taylor rule.

By contrast buying of Treasuries brute forces long rates down. The timing and impact may not be as precise as central bankers might desire but there is a pretty good case that if they buy enough bonds for long enough, bond yields will come down. This is a first order effect. If the central bank bond-buying spree leads some traditional bond-buyers to desert the bond market, the impact may be shifted to equities and other assets, but it is still there.

That’s the view from a practitioner, and it applies to both domestic and cross-border assets. In addition to this perspective, I’d add the following point, drawn from a portfolio balance framework. If short and long term Treasury bonds were perfect substitutes, then credit easing would have no impact, as many asserted (of course, this must mean that agents are risk neutral, or close to it …) I’m willing to stipulate perfect or near perfect substitutability is plausible.

However, it seems less clear to me that domestic and foreign assets are perfect or near perfect substitutes. The less substitutable, the bigger the impact, ceteris paribus.

Here is some quick and dirty evidence, from a trivariate VAR, with advanced country financial stress, the money base/GDP ratio and the dollar’s value (in first differences).

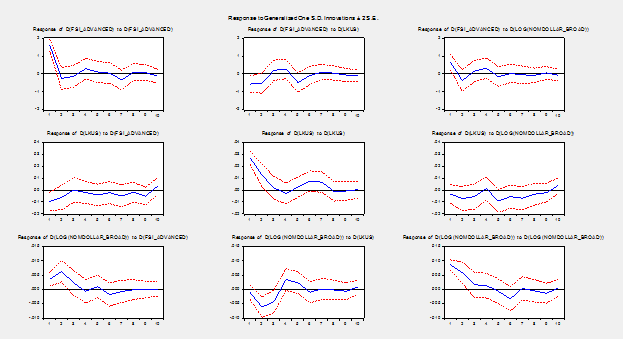

Figure 1:Impulse response functions for VAR (6 lags, in first differences) of IMF advanced country financial stress, US money base to GDP, and US dollar value against broad basket of currencies, 2009M01-2013M03. Decline in dollar indicates depreciation; generalized impulses. Source: IMF, Federal Reserve Board, BEA, and author’s calculations.

The results of this simple VAR indicates there are safe haven effects (when advanced country financial stress rises, there is a flight to the dollar). For our purposes, the important point is that the dollar depreciates in response to an increase in the money base; the responses are statistically significant at 2-3 months. These IRFs are shown for generalized impulses; using a Cholesky decomposition yields similar results.

My caution: Just because QE/CE has apparently small impacts on interest rates doesn’t mean that those measures necessarily have small effects on all asset prices.

For discussion, see this post, and for a survey of empirical evidence, see this paper.

Update, 9/5 1PM Pacific: On a related note, see Joe Gagnon on Misconceptions about bond buying.

Dear Menzie,

You mention that Cholesky irs yield similar results. Could you let me know the ordering of variables in this case? Can you perhaps refer me to a paper that uses this ordering?

Thank you for a great post and kind regards,

Vasja

I apologize for double posting. I read the cited paper. I would though still like to ask if there is any paper that justifies the chosen ordering of the variables.

Thank you and kind regards,

Vasja

vasja: I don’t know of a specific study justifying the ordering, but I think for this sample period, (2009M01-13M03), it is reasonable to assume financial stress is more exogenous relative to monetary policy, and that monetary policy more exogenous relative to the dollar (so, ordered as in the figure — stress, money base, dollar). You could exchange the ordering of dollar and money base, and still get a similar IRF for dollar response to money base.

“However, it seems less clear to me that domestic and foreign assets are perfect or near perfect substitutes. The less substitutable, the bigger the impact, ceteris paribus.”

? Suppose domestic and foreign bonds are quite close substitutes, so fed purchases of U.S. bonds causes U.S. lenders to replace them with foreign bonds. Wouldn’t this cause a sharp exchange rate effect? Does this make the fed purchases less effective than if the foreign bonds were poorer substitutes and the fed purchases led to smaller international capital flows?

I congratulate President Obama for pulling the American people together. They are solidly, Democrat and Republican, opposed to his plans for war in Syria. Even Bush could never get this kind of unity of opinion.

To elaborate on my question above, international capital flows caused by interest arbitrage are matched by current account changes. For example, a move toward euro area assets by U.S. investors caused by Chair Bernanke’s QE policies directly improves the U.S. current account, but worsens those of the euro members, helping the U.S. economy, but weakening theirs.