On Wednesday the Federal Reserve announced that it is increasing its target for the fed funds rate to a new range of 25 to 50 basis points (0.25% to 0.5% annual rate). How does the Fed plan to accomplish this, and what does it mean for other interest rates?

The fed funds rate is the interest rate on an overnight loan of Federal Reserve deposits (accounts held at the Fed) between depository institutions. Because this is a market rate between private parties, the Fed does not control it directly. In the old days, the Fed controlled it indirectly by making use of the fact that the fed funds rate was very sensitive to the quantity of excess reserves (deposits held in excess of requirements). The Fed could change excess reserves directly by increasing or decreasing the supply of deposits through open-market operations. The Fed would pay for a Treasury security that it purchased through an open-market operation by creating new deposits, and the new excess reserves would depress the fed funds rate that emerged in equilibrium. That worked when excess reserves were around $5 to $10 billion. Today we’re talking about $2.5 trillion in excess reserves. Changing excess reserves today by a few hundred billion doesn’t matter in the slightest for the fed funds rate.

Instead of open-market operations, one of the key new tools of monetary policy is the interest rate that the Federal Reserve pays on deposits kept overnight on account with the Fed. This rate had been 25 basis points and was raised to 50 basis points on Wednesday. One’s first thought would be that this interest rate should put a floor under the fed funds rate. Why would I accept less than 25 basis points on a potentially risky loan to another bank when I could earn 25 basis points just by letting the funds sit idle in my Fed account without risk? But it’s clear that the system hasn’t worked that way. The average fed funds rate over the last two years has only been around 10 basis points, despite the 25 bp banks could earn just by sitting on the excess reserves.

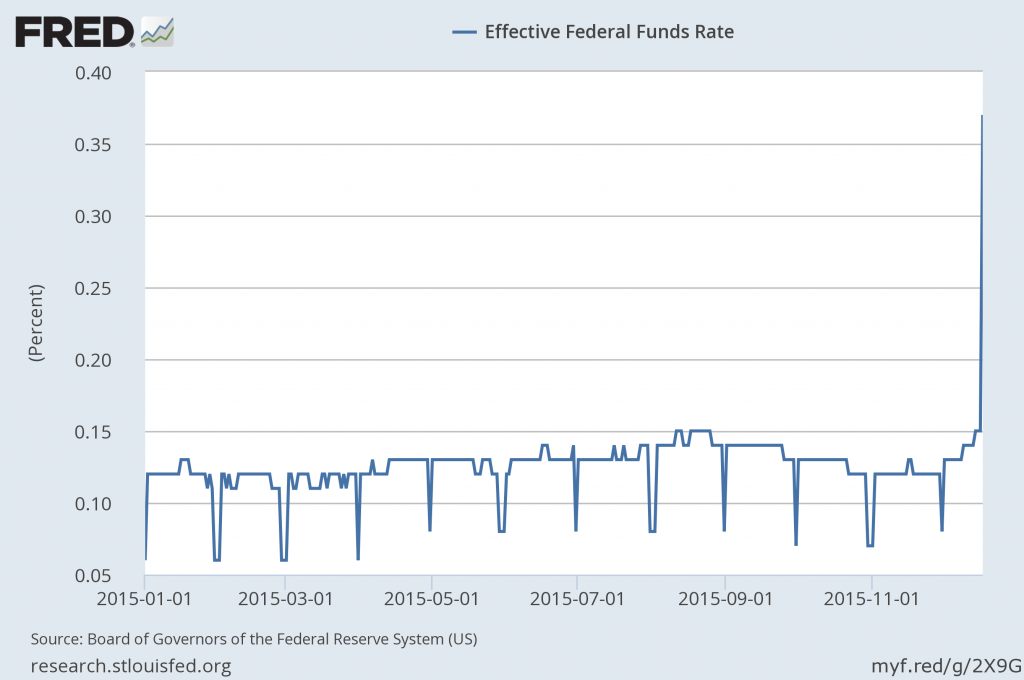

Volume-weighted average of rate on each day’s fed funds loans. Source: FRED.

The explanation is that most of the institutions lending fed funds today are not conventional banks but instead are institutions like Federal Home Loan Banks that are not eligible to earn the 0.25% interest on excess reserves. Still, you’d think that any of the banks that are eligible would be happy to pay well more than 10 basis points to borrow as many Fed deposits as they could from the FHLB and then collect the 25 bp from the Fed. But the FHLB are picky about whom they’re willing to lend to, and as a result settle for well below what would be an unrestricted market rate. Incidentally, we also see very dramatically in the graph above an important monthly seasonal in these preferences. Many institutions are apparently doing something other than lending fed funds to their approved borrowers on every day except the last day of the month, the day when their monthly balance sheet gets reported.

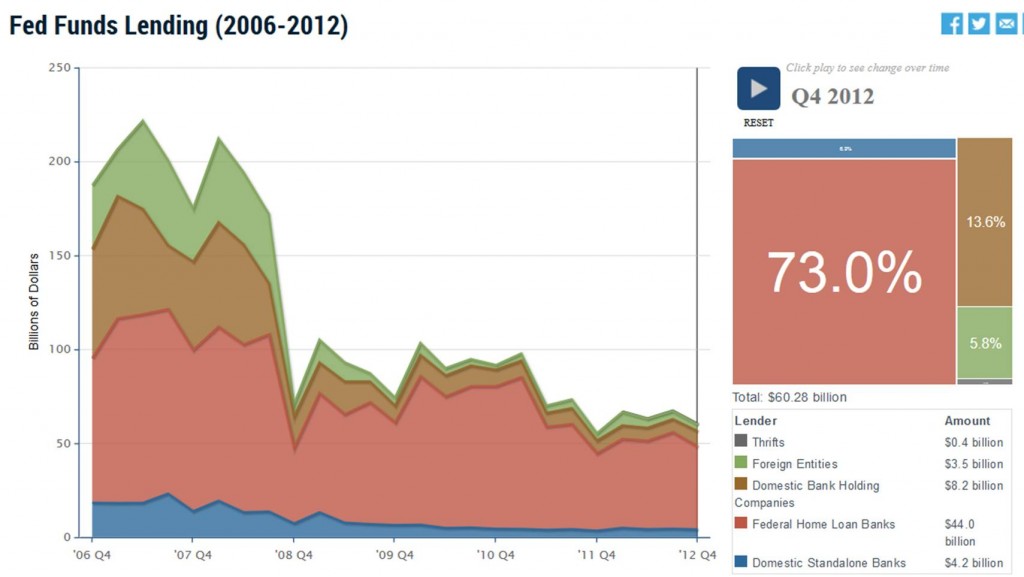

Fed funds lent by institution, 2006-2012. Source: Liberty Street Economics.

So in addition to raising the interest rate on reserves, the Fed announced Wednesday that it will offer to pay 25 basis points on reverse repurchase agreements to an expanded list of counterparties that includes the Home Loan Banks, Fannie, Freddie, and a host of money market funds. These are essentially overnight loans from the institutions to the Fed of up to $30 billion per institution which are collateralized by the Fed’s holdings of Treasury securities (the source of the “reverse repurchase agreement” designation). The Fed intends to keep the fed funds rate within a given target range (currently 25 to 50 basis points) by setting the interest on reserves to the upper end of the range (now 50 basis points) and the offer rate on reverse repos to the lower end (now 25 basis points).

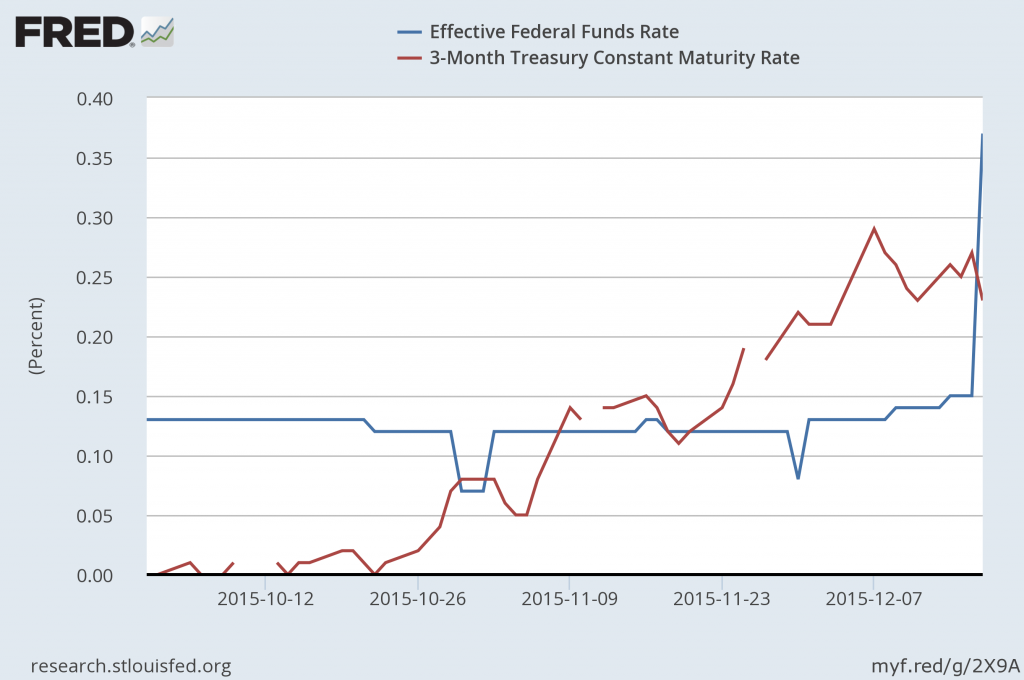

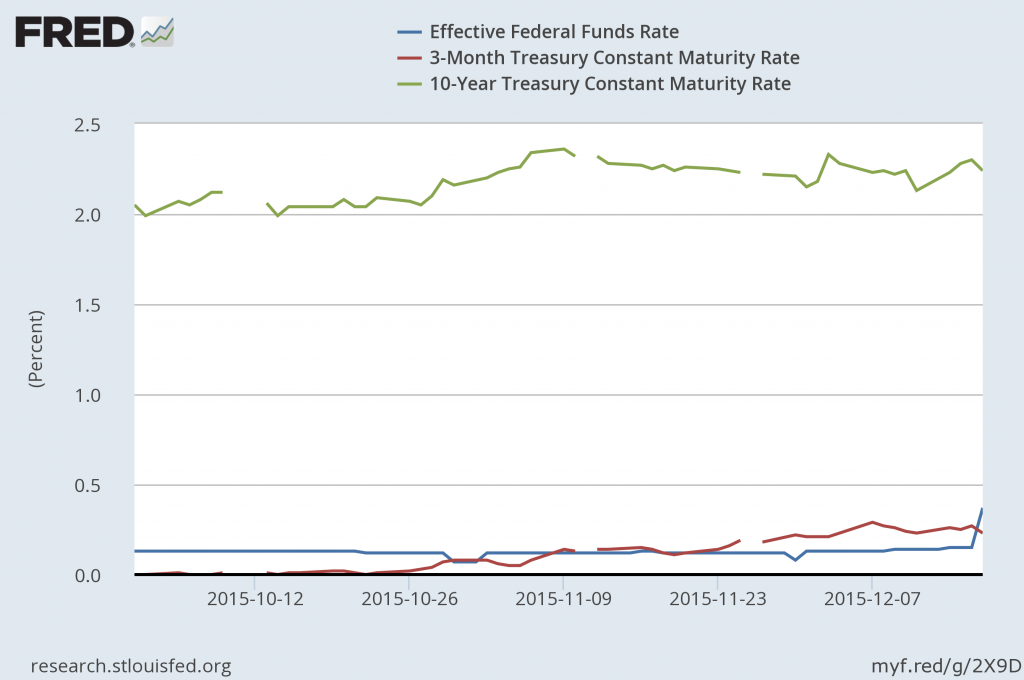

Is it going to work? As seen in the first graph above, the changes certainly seemed quite effective on the first day of operation, with the average rate on fed funds loans jumping from 15 basis points on Wednesday to 37 bp on Thursday. But other interest rates actually fell on Thursday, with the yield on 3-month Treasuries falling from 27 to 23 bp and that on 10-year Treasuries falling from 2.30% to 2.24%. Was this some kind of perverse market reaction to the change?

The answer is not at all. Financial markets are forward looking. You can think of the interest rate on a 3-month Treasury bill as the expected average value of the overnight fed funds rate over the next 90 days minus a habitat premium representing investor preferences for Treasuries. That premium has recently been averaging around 7 bp. Wednesday’s move by the Fed caught no one by surprise. The Fed’s October 28 statement and statements by Fed officials in the following weeks made it pretty clear to everybody that December 16 was the lift-off date. And we saw the 3-month Treasury rate begin to rise at the end of October. The cumulative rise between October 23 and December 17 was 23 bp, consistent with the claim that the Fed has succeeded in raising the 3-month Treasury rate exactly as desired. That number is also consistent with the conclusion that nobody expects a further increase at the next FOMC meeting on January 27. The one uncertainty is where the fed funds rate will end up trading within the 25-50 bp range. If that same 7 bp premium holds over the next 3 months, Thursday’s 0.23% Tbill rate would be consistent with an average fed funds rate of 30 bp over the next 3 months.

Effective fed funds rate and 3-month Treasury bill rate, daily Oct 1 to Dec 17, 2015. Source: FRED.

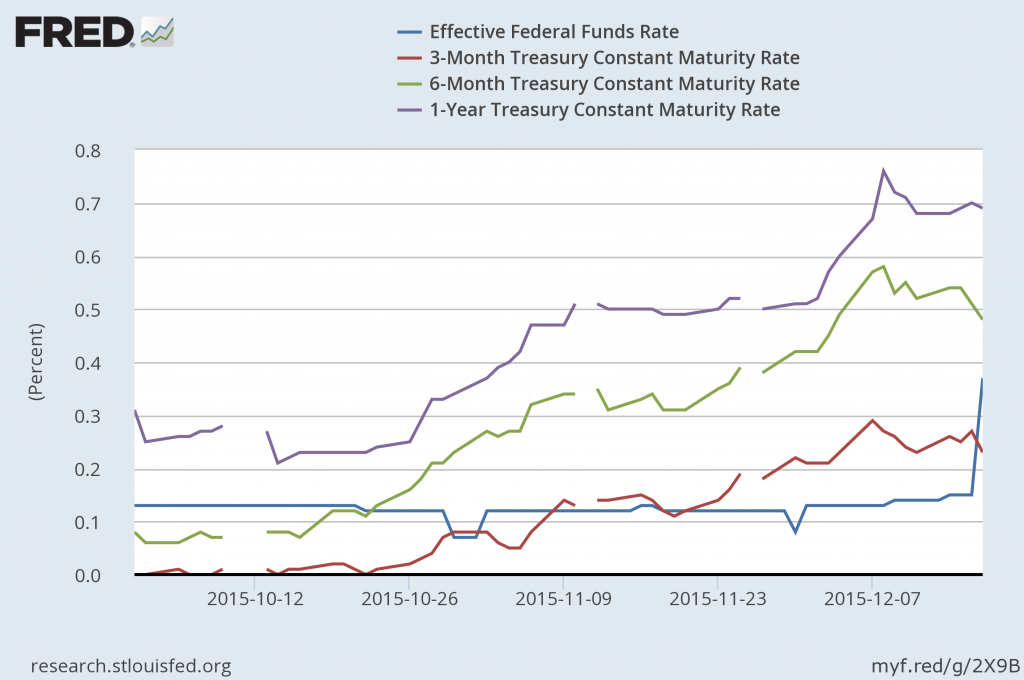

The rest of the yield curve also started climbing right along with the 3-month yield at the end of October. The 6-month rate is up 35 bp, and the 1-year up 45 bp. Once you get past about 3 months, risk premia start to become a factor in the Treasury yield curve– the yield is not simply an expectation of the average fed funds rate over the period minus some constant. Nonetheless, the change in yields since October is consistent with a second fed funds hike expected in the first half of 2016 and a third later in the year.

Effective fed funds rate and yields on 3-month, 6-month, and 1-year Treasuries, daily Oct 1 to Dec 17, 2015. Source: FRED.

The 10-year yield (which in principle should reflect the entire future rate path over the next decade) is up about 25 basis points.

Effective fed funds rate, 3-month Treasury bill rate, and 10-year Treasury bond yield, daily Oct 1 to Dec 17, 2015. Source: FRED.

The Fed’s new tools give it the power to raise interest rates in the new environment. But they may be quite cautious about exercising that power in 2016.

Part of the rise in the 3-month treasury bill since October is due to the raising of the the debt ceiling (and thus uncertainty about supply) along with the change in Treasury policy to fund more of the debt in the shorter term securities.

A few questions:

1. If the Fed foresaw the day of raising interest rates / decreasing the quantity of ER, why didn’t they simply employ repos (reverse repos?) such that they were selling back treasuries at pre-ordained rates, thus removing those trillions of ER, ending their effective borrowing from banks and getting their BS back to “normal?”

2. I don’t follow how the current action will not eventually put more ER, and subsequently “dead presidents” into circulation, as they are borrowing, and thus paying out more than if they had followed a course of action to remove the ER from circulation.

3. Long ago, I believe you wrote about watching the velocity of money/fund(?) as a key parameter to watch to understand how much ER were being lent out, and thus an indicator of future inflationary pressures. How do you expect velocity to change as the interest rates are raised?

The Fed sells bonds to raise the Fed Funds Rate and drain money out of the commercial banking system.

Some banks have excess reserves and some don’t.

When the real economy picks-up, the velocity of money will pick-up too.

If interest on excess reserves creates too much money in the system, it would depress the Fed Funds Rate. So, the Fed would sell more bonds.

That’s an interesting post, didn’t know that.

In 2016: a smooth 0,25 % for 4 times would fit to Yellen’s repertoire.

The Fed taketh via the Fed funds rate . . . and then giveth back by way of interest paid on reserves held at Fed banks. Net nuthin’.

The real yield spread, 2-year yield, and rate of real final sales per capita imply that the de facto caps on the Fed funds and discount rates are ~1.25-1.3%, i.e., as was the case in the 1930s and Japan since the late 1990s.

But the US economy is decelerating for the cycle to a 4-qtr. real SAAR per capita of ~1.3%, therefore, I don’t anticipate that the Fed will be able to raise the funds rate to anywhere near 1.25-1.3% in 2016.; rather, I expect that the Fed will be required to resume QEternity at some point in 2016, as the deficit/GDP widens and profits/GDP crash for the cycle, requiring a similar liquefying of the banking and financial systems that occurred during the GFC.

This implies a post-2007 secular nominal GDP per capita of less than 2% (slowest since the Great Depression, 1890s, and 1830s-40s).

Thus, don’t be surprised if we see a debt and equity market crash;

profits/GDP plunging from ~11% to 5% or below (loss of business income to GDP of $1.1 trillion, which is equivalent to $1.7 trillion including gov’t spending);

Warren Buffet’s Berkshire crashing 55-60% from the cyclical/secular peak, requiring a de facto direct and indirect bailout;

the industrial recession spreading to the rest of the economy;

housing rolling over;

auto sales contracting YoY and subprime auto loan delinquencies and charge-offs soaring;

a return of $1 trillion deficits/GDP;

a 1% 10-year yield or lower;

the yield curve flattening at ~0% CPI and periodic deflation and no ability for the Fed to engineer a reflationary negative real yield spread (like Japan since the early 2000s);

bank C&I loan delinquencies and charge-offs accelerating YoY;

bank lending and thus money supply less bank reserves decelerating, i.e., deflationary; and

the Fed (TBTE banks) resuming QEternity by the end of Q1 or at some point in Q2 2016, resulting in an increase in the Fed’s balance sheet to $6-$7 trillion by 2017-19, reaching 40% or more of GDP, not unlike Japan today.

The unambiguous consensus is that the US (and EZ) is (are) not Japan, and the self-deceit has become fully articulated and internalized, despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

The Fed is raising rates today precisely at the most inauspicious moment because the Fed’s owners, the TBTE banksters, know that the cycle is rolling over, bear markets in junk and IG debt and equities have begun, Housing Bubble II is deflating, and a global, deflationary recession is imminent; therefore, as in 2000-01 and 2007-08 when the TBTE banks were shorting Dotcom stocks and hopelessly levered, insufficiently hedged, junk unreal estate derivatives, the TBTE banks are shorting overvalued assets and fully expect to profit from a crash and then be liquefied by the Fed and bailed out by the gov’t they own during the next global deflationary recession and bear market, which is likely to be the worst in world history.

Prepare accordingly.

Apologies

My reference to the Velocity of Money was wrong. I was thinking of the below, which I recalled as being an important post by the good professor:

“…The Fed’s plan when that starts to happen is to remove some of those reserves by selling off some its assets, and preserve the incentive for holding reserves by raising the interest rate paid on them…”

https://econbrowser.com/archives/2011/03/velocity_of_fed

What constitutes “selling,” in the above? Is there legally / economically a “sale” with any form of repo? “Give it back, with interest” seems, in substance, a loan. No? Indeed, one that keeps adding, and adding, to ER held at the Fed.

Perhaps this is a better way to frame my question #2:

if there’s no sale, doesn’t the Fed just keep putting more “cash” on the banks’ account at the Fed (in the form of ER via interest paid on ER or repos)? Where’s the drain, where do those ER go to die?

Assuming they continue with ER payments/Repos: Don’t the banks—as they seek better returns than the interest on ER/repos– eventually create loans to John and Jane Doe and we wind up with a rinse/repeat bubble situation? Will we know this by watching “Velocity of Federal Reserve Deposits?”

Again, apologies for my lack of clarity in the original post; just looking for thoughtful insights.

I may have been too quick for my praise for Janet Yellen. I actually thought she was holding the value of the currency stable while all along she had no idea what she was doing and the currency was stabilizing all by itself because there simply is no new business activity. We are limping along trying to reduce costs on our existing business base. No one wants to borrow and expand. The risks are just too high.

Her justification of for raising the the FFR was more than absurd. She justified her move by referencing the totally discredited Phillip’s curve with language not heard since before the 1980s. Why?

Employment is good, even though half of the work force not participating.

We must fear non-existent inflation and raise interest rates because we have to curb inflation that might or might not return in a couple of year.

And we also need to have ammunition in case we need to stimulate the economy, so we raise interest rates because low interest rates have not stimulated the economy so that later we can lower interest rates in the hopes that will stimulate the economy.

I don’t think I have seem more stupid smart people in my life.

ricardo, be careful. one might confuse you for krugman! aggregate demand problem. future inflation problem which may or may not manifest itself. you have become a keynesian!

Ricardo, don’t fall into the trap of blaming the Fedsters, one of their unspoken mandates being to run political cover for the TBTE banksters’ license to stead.

The Fedsters work for the TBTE banksters, who made the decision more than a year ago that they were going to pull the plug on the bubble machine, beginning the process in earnest in Q1-Q2, setting up another global deflationary recession and debt and equity bear markets in 2016-17.

So, prepare for WTI at $25-$30; another 50% bear market; doubling of the U rate; Housing Bust II; deficits of $1 trillion; the Fed expanding its balance sheet by at least $2-$2.5 trillion; a bailout of banks’ energy sector C&I and commercial real estate loans, subprime auto loans, student loans, MBS, and perhaps munis; and the 10-year Treasury yield at 1% or lower.

BC,

Don’t misunderstand me. The FED is a group of over-educated Sudoku players being paid high salaries, ultimately by the tax payers, to pretend they know something. My God! It just struck me. Whey are all Donald Trump!

I’m not sure responses in fed funds and Treasury rates tell us much about whether the Fed is able to perform its ultimate task of regulating financial conditions for the real private sector.

1. I’ve tried to count the number of pieces that describe how the actual mechanism works this time. Other than ones here, which don’t get newspaper circulation, I remember one long piece in the NYT and one short one in The Economist and a few references here and there with little explanation. Given the number of times I’ve had to explain this process to people, I’ve become more convinced the financial press industry is more illiterate than they let on. I’m trying to be kind.

2. I wonder if future increases are as likely to hold. If the rate drifts toward .50, that would seem to increase the odds, but I think literally everyone in the banks/non-banks/etc. wanted to get further from 0 and so this was the easiest hike to pull off. But the expansion is aging and fueled by oil price decreases (in the heating season, no less!), and without that nagging 0 staring us all in the face … how much can they really do and at what cost? I don’t see the vast excess reserves leaving the system for a while, so to get rates to 1% would mean paying that much – more, if we think of the lower end of a range – just to push the needle. It makes me wonder: philosophically, is it really a rate increase if the rate range is being held up artificially against the push toward lower? That could become a problem. Not a “bubble”, since people love to say “bubble”, but a problem in which the Fed has to fight to hold rates up. I don’t remember that happening before, either in holding rates up or down.

BC, I agree with your assessment of the economy and where it is headed. What are the implications for the $USD? Typically I would say that collapsing growth and short rates would bring it down, but with other central banks easing its basically just an neautralizing offset. Am I missing something here?

Thank-you Professor,

for a much appreciated explanation of the change in monetary policy.

I suspect that the Fed believes it’s policy is preemptive, getting ahead of impending inflationary pressures. Certainly understandable on two counts; so often the Fed has been late in recognizing future inflation, and recognition of its uncharted creation of massive reserves.

I have a sinking feeling that its policy is so blunt that it will cause continued deflation in short and medium term. Do you see eventual negative interest rates on reserves? Roller coaster ahead.

Ed

What amazes me is that our past three FED Chairs have admitted they had no idea what is going on or what they are doing yet they still keep getting paid.