Today we are fortunate to be able to present a guest contribution written by Mark Copelovitch (University of Wisconsin – Madison), Christopher Gandrud (City University of London), and Mark Hallerberg (Hertie School of Governance, Berlin).

Sovereign borrowing costs on the Eurozone’s southern periphery spiked again last week amidst renewed fears of a “Grexit” and rising concerns about non-performing loans on the books of European banks. This past week, Portuguese bond spreads over German Bunds hit their widest level since March 2014, while Italian and Spanish yield spreads reached their widest levels since last summer. At the same time, Germany’s largest bank, Deutsche Bank, has seen its stock fall more than 40% in 2016, while its CDS rates have more than doubled, forcing CEO John Cryan to state that the bank “remains absolutely rock solid” (link) and prompting German Finance Minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, to publicly state “No, I have no concerns about Deutsche Bank.”

At the heart of these market concerns are the content and consequences of new rules to resolve failing Eurozone banks, which came into force on January 1, 2016, as part of the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM), or the second pillar of European banking union. The rules, which are codified under the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD), are designed to limit further taxpayer-funded bank bailouts within the Eurozone by imposing losses directly on a failing bank’s creditors and requiring “living wills” for all 129 banks directly under European supervision. The Directive mandates that 8 per cent of a bank’s total liabilities must be wiped out before any taxpayer support can be provided. This “bail-in” mechanism creates the possibility that bondholders and some depositors will be forced to take losses if a Eurozone bank is deemed insolvent. Such losses occurred previously in Portugal, where the Portuguese central bank applied the BRRD already in December 2015, and wrote down €2 billion in bonds at Novo Banco, and in Cyprus during the 2013 bailout, where large depositors took direct losses. While the SRM is designed to limit uncertainty in the case of Eurozone bank failures, investors remain concerned that – in the absence of fully-funded and operational European deposit insurance – national governments (and taxpayers) in individual member-states remain ultimately liable for covering the cost of bank failures in the Eurozone. These concerns have risen since October, when the ECB released the results of its Comprehensive Assessment, which estimated €826 billion in non-performing loans on the balance sheets of banks under the mandate of the first pillar of banking union, namely the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM).

Thus, six years after the onset of the Euro crisis, fears persist among policymakers and investors of a sovereign “doom loop” linking problems in the European banking sector to sovereign debt. The central concern is that weak or failing banks will require national or subnational governments to step in and provide bailouts – as occurred in Ireland in 2010, and in Germany in 2007-9 – that will, ultimately, lead to greater fiscal deficits, higher levels of sovereign debt, and potentially a greater risk of sovereign default.

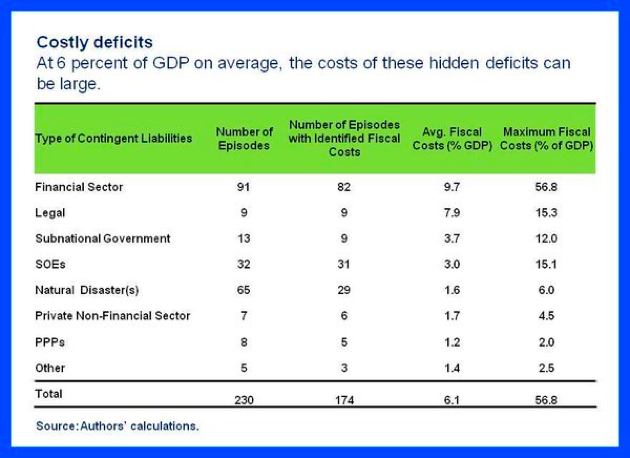

As highlighted in new IMF research by Bova et. al, such contingent sovereign liabilities can have significant economic and fiscal costs. These “hidden deficits” frequently impose large fiscal costs on the government, in the form of bank bailouts, backstopping the liabilities of subnational authorities, or financial rescues of state-owned enterprises. As the authors note, taxpayers and investors often only know about the true magnitude of these sovereign liabilities once a crisis hits and hidden liabilities become “actual.” In order to minimize uncertainty and risk, they recommend that governments “put in place more transparent and better arrangements for disclosing and monitoring their hidden liabilities. In particular, fiscal frameworks should be strengthened to enhance discipline and limit the excessive growth of contingent liabilities. This is particularly important because the evidence shows that these hidden liabilities tend to emerge in times of financial distress when public finances are the weakest.”

SOURCE: Bova, Ruiz-Arranz, Toscani, and Ture 2016. While the title of their graph concerns “costly deficits,” it is important to note (as they indicate themselves in their text) that they focus on “fiscal costs,” which may or may not appear as changes in public sector budget deficits. In many cases in accounting terms, the increases in costs count directly against the gross debt burden but do not affect a country’s public sector budget deficit.

In a new working paper, we explore whether greater financial regulatory transparency actually has the salutatory effects anticipated by Bova et. al on sovereign risk by making governments’ contingent liabilities to the private sector more visible and transparent.[1] The first step is to create a way to measure the transparency of the data that the government regulator makes available on the health of its banking sector. Using a Dynamic Hierarchical Bayesian Item Response Theory (IRT) approach, which was originally created for educational testing purposes, we develop a new Financial Regulatory Transparency (FRT) Index. It measures a regulator’s latent willingness to report minimally credible data about its financial system to international organizations and investors. The FRT Index covers 68 developed and developing countries from 1990 through 2011. It measures these countries’ reporting of financial system information to the World Bank’s Global Financial Development Database. The Index is a unique indicator of countries’ willingness to reveal the structure of their financial system and their regulatory quality, since the data has to pass minimal World Bank and International Monetary Fund quality checks. If a country reports these data, it is easier for international investors and other market participants to scrutinize the banking system and to ascertain whether a government is exposed to large-scale contingent liabilities in the financial sector. To date, no broadly recognized measure of financial regulatory transparency exists. The FRT index fills this data gap.

In our paper, we use this FRT index to consider whether increased financial regulatory transparency is related to changes in sovereign borrowing costs. The expectation is that markets pay attention to the relative stability of the banking sector. They anticipate that financial instability or a crisis will lead to a big increase in the public debt burden. We expect that states with higher FRT scores have lower and more stable borrowing costs. However, we argue that this effect should also be conditional on a country’s fiscal position. Investors facing information gathering and utilization costs try to maximize the net marginal benefit of gathering information and will pay more attention to countries with precarious fiscal situations.

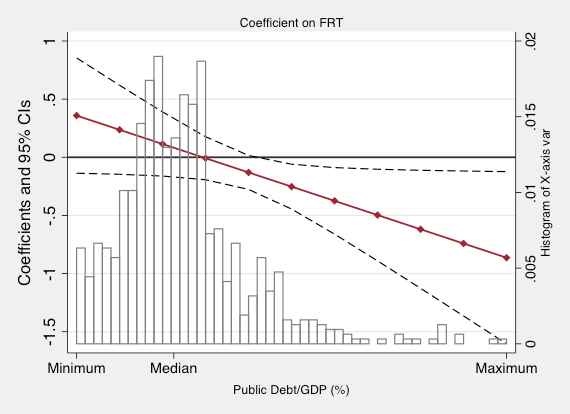

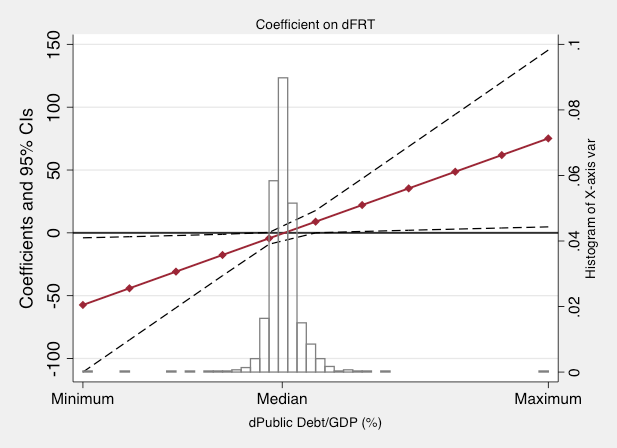

In our empirical analysis, we find that financial transparency – both its level and change – has a significant effect on sovereign bond spreads, but that these effects are highly conditional on a country’s public debt levels. Higher levels of FRT reduce changes in spreads (Figure 1), but only if a country is already heavily indebted (debt/GDP exceeds approximately 100%). Similarly, increases in FRT are associated with a reduction in spread changes, but only when debt levels are falling rapidly (Figure 2). Conversely, positive changes (increases) in FRT are associated with an increase in spread changes, but only when debt is rapidly increasing.

Figure 1: Marginal effect of FRT (level) on Change in Bond Spreads at Different Values of Public debt/GDP (level)

Figure 2: Marginal effect of FRT (change) on Change in Bond Spreads at Different Values of Public debt/GDP (change)

Together, these results imply that increased financial regulatory transparency is beneficial for countries seeking to access international capital markets, but only if such countries are 1) already heavily indebted; and 2) in the process of reducing their debt burdens. For countries that have modest debt-to-GDP ratios, transparency has no significant effect on borrowing costs. And for heavily indebted countries whose debt burdens are still increasing rapidly, transparency appears to exacerbate pressure on borrowing costs.

These findings help us to understand the uneasy market reactions we have observed in Europe over the past month. In the medium-term, greater transparency about the status of European banks’ balance sheets, along with clear and explicit rules about “bail-ins” under the new SRB, may cast light on Eurozone governments’ contingent liabilities to the private sector and help to break the sovereign-bank “doom loop.” In the short-term, however, these increases in transparency have only increased fears about bank insolvency and sovereign debt in the Eurozone, particularly in the Eurozone’s largest debtor countries. This was most clear last month, when the ECB sent a questionnaire about non-performing loans to a sample of lenders from across the SSM to “inform its work,” which triggered a rapid sell-off of Italian banking stocks amidst uncertainty about which banks were most at risk.

Ultimately, our analysis suggests that greater financial regulatory transparency is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, more transparency may make explicit and visible the contingent liabilities and implicit guarantees that link banks and sovereigns. On the other, heightened transparency – particularly if it is pursued in times of increasing debt and financial stress – may exacerbate investors’ concerns and trigger the very instability that it intends to address. Consequently, both within Europe’s nascent banking union and beyond, regulators need to proceed cautiously as they seek to gather and disseminate better, and more extensive, data about the health of their financial systems.

[1] For further details on the implications of our data and findings for the future of European banking union and financial regulation, see our related Bruegel policy brief: http://bruegel.org/2015/12/financial-regulatory-transparency-new-data-and-implications-for-eu-policy/.↩

This post written by Mark Copelovitch, Christopher Gandrud, and Mark Hallerberg.