Bryan Kelly at the University of Chicago, Hanno Lustig at Stanford and Stijn van Nieuwerburgh at NYU had an interesting paper in the June issue of American Economic Review that used option prices to measure the magnitude of the implicit U.S. government guarantee of the financial sector during 2007-2009.

A put option is an agreement you could make that you gives you the opportunity (if you choose to exercise it) to sell a security at some specified price and future time. If the agreed-upon price is well below the current price, you are basically buying insurance against a very big move down in the stock price. How much you pay for the option depends on the likelihood you and the counterparty place on the stock price going that low and on how much you value being insured against that contingency.

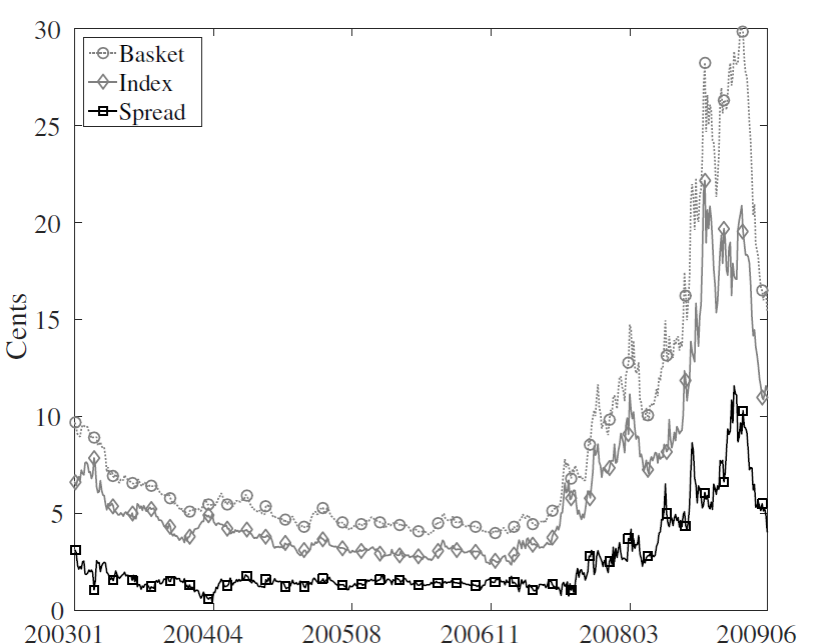

You could buy put options on a variety of securities, both individual stocks and indexes constructed from groups of stocks. The key observation motivating Kelly, Lustig, and van Nieuwerburgh’s paper is a divergence in 2007-2009 between the combined price of put options on individual financial-sector stocks and the price on options for an overall financial-sector index. During the Great Recession, you started to pay much more for a dollar of insurance against any individual financial stock going down than you would for a dollar of insurance against the whole sector going down.

The cost of financial sector insurance based on 365-day put options (delta = -25%) on the index (solid gray line) and a basket of options on individual stocks (dotted gray line), as well as the basket-index spread (black line). Units are cents per dollar insured. Source: Kelly, Lustig, and van Nieuwerburgh (2016).

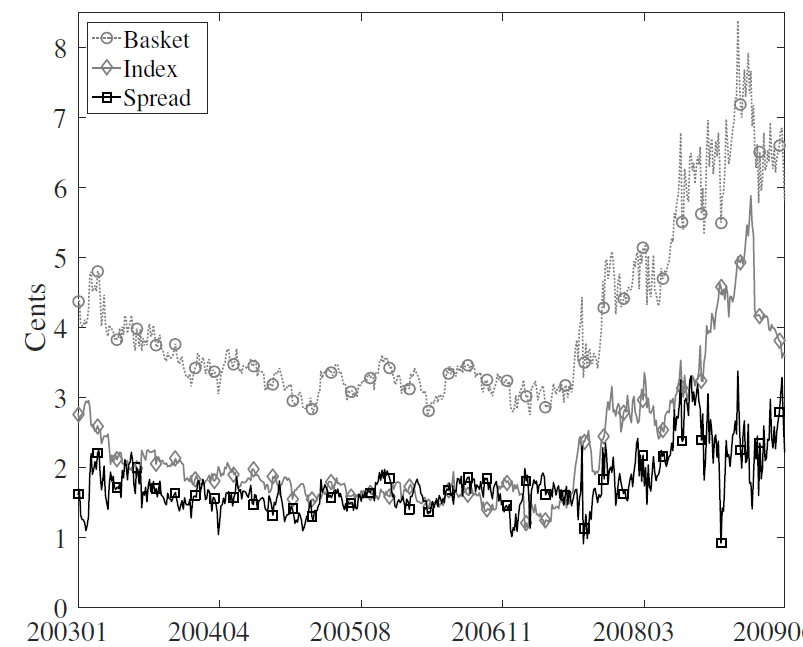

One possible explanation would be if firm-specific risks went up. But the correlation between financial-sector stocks increased rather than fell during this period. And we see no corresponding spread develop in the prices of call options (where I pay you for the option of buying at some future price).

The cost of financial sector insurance based on 365-day call options (delta = +25%) on the index (solid gray line) and options on the basket (dotted gray line), as well as the basket-index spread (black line). Units are cents per dollar insured. Source: Kelly, Lustig, and van Nieuwerburgh (2016).

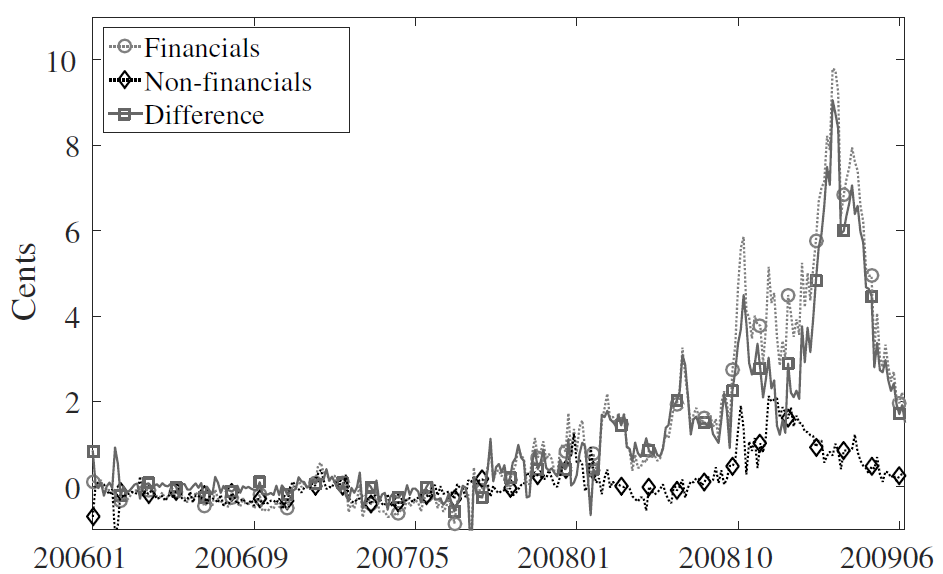

We also did not observe an analogous price spread between individual put options and sector-wide put options for nonfinancial stocks.

Basket-index spreads (puts minus calls) for the financial sector (marked by circles), the non-financial sector (marked by diamonds) and their difference (financials minus non-financials, marked by squares). Units are cents per dollar insured. Source: Kelly, Lustig, and van Nieuwerburgh (2016).

The authors examined a number of other possible factors, and concluded that the single most plausible explanation is that while the government may have been prepared to let individual banks suffer big losses, it stood ready to provide whatever assistance was necessary to prevent a big drop in the entire sector, a policy that some observers have referred to as the “Greenspan/Bernanke put”. The authors constructed an option-pricing model that incorporated this perception on the part of option traders which allowed them to estimate parameters of the perceived policy to be able to explain the observed option prices. They then used this model to ask, suppose there had been no government guarantee, but you wanted to buy an insurance policy covering the entire financial sector that would function the same way. They concluded that such a policy would have cost $282 billion. Here’s how the authors describe that number:

These estimates are admittedly coarse and derived from a highly stylized model, thus they are not to be interpreted as estimates with high statistical precision due to uncertainty about the correct model specification. Nonetheless they suggest meaningful effects of government guarantees on the value of equity and equity-linked securities.

There are those who claim that the government’s goal was to protect the banks. I do not share that view, and maintain that instead the government’s goal was to prevent collateral damage from a financial-sector collapse. The trade-off all along was to try to make sure that as much of the out-of-pocket costs as possible were paid by bank owners and management while minimizing collateral harm to the non-bank public. Whether we found the right way to balance those trade-offs is something that will still be debated.

But I think we can all agree that what the government did was a pretty big deal.

We also know from market pricing that the government subsidized the banks with TARP money. The TARP money was loaned at 5% interest, but we know the actual market price for money to risky banks was much higher. Goldman Sachs was forced to pay Warren Buffett 10% plus stock warrants to get money on the open market. The difference between the market rate and the TARP rate amount to a handout from the taxpayers to the banks.

Another taxpayer handout was permission for conversion of investment banks that had fiercely maintained their independence from Fed oversight for decades literally overnight into commercial bank holding companies to permit access to the discount window to prop them up. This is like being able to buy fire insurance after you bank is already on fire, another gift from taxpayers to incompetent bankers.

We alsoknow that the USG paid out 100 cents on the dollar on CDS sold by AIG. Any policy that sought to “try to make sure that as much of the out-of-pocket costs as possible were paid by bank owners and management” would have required a discount. But that would have cost Goldman Sachs shareholders money and Lloyd Blankfein his job.

It would seem, over time, if you hedge to eliminate 100% of stock market risk, you eliminate 100% of stock market return. If true, why would anyone invest?

Zero risk = zero return?

A lot of billionaires have been buying puts. If the stock market is mean reverting (rather than a random walk), then they’re betting it’s above the mean and will fall towards or below the mean. Of course, timing and managing risk are important.

What ticks people off isn’t so much that the government had to bail out the financial sector in order to protect against collateral damage from a financial sector meltdown. Most people understand that some times you just have to hold your nose and do what needs to be done. Most people understand that it’s not a good idea to cut off your nose to spite your face. But what people don’t understand is why, even after Dodd-Frank, half a dozen of the usual suspects paid out $139B in fines over a two year period….and no one of any importance ended up wearing an orange jumpsuit. How much lower would that $282B subsidy have been if bankers in the early 2000s knew they would spend the rest of their lives doing hard labor if the financial sector collapsed due to their corruption?

Reference for the $139B figure: NBER Working paper #20894, Table 1.

If bankers knew in the early 2000s they would spend the rest of their lives doing hard labor if the financial sector collapsed, they wouldn’t make risky loans. However, the fines were enough to send the signal to severely limit lending risk, and therefore contribute to the depression, since 2009. The fines shifted blame away from Congress, which encouraged increasingly risky loans before the crisis, while also collecting lots of money – something politician-lawyers are actually good at.

Michael Bloomberg, former Mayor of New York City:

“It was not the banks that created the mortgage crisis. It was, plain and simple, Congress who forced everybody to go and give mortgages to people who were on the cusp.

Now, I’m not saying I’m sure that was terrible policy, because a lot of those people who got homes still have them and they wouldn’t have gotten them without that.

But they were the ones who pushed Fannie and Freddie to make a bunch of loans that were imprudent, if you will. They were the ones that pushed the banks to loan to everybody. And now we want to go vilify the banks because it’s one target, it’s easy to blame them and Congress certainly isn’t going to blame themselves.”

as usual, an ex banker who contributed to the financial crisis and lost his job is still unwilling to own up to the stupidity and recklessness of the financial sector, and would rather simply blame the government. now regarding bloomberg, i actually like the guy. but his statement is inaccurate, and you like to post it on this site like fact. the loans that blew up the financial sector at lehman and bear and aig were not fannie and freddie, they were private sector reach for yield with absolutely horrendous risk management policies. important point here is private sector.

And, here’s what a post-crisis study concluded:

“Each institution must find its own path to prevail in this era of relentless regulatory oversight, new standards of conduct, and rigorous enforcement,” the report said.

To be a successful bank in this new era, each bank has to redefine the “very nature of risk,” and total transparency is not a new catchphrase but a new permanent defining part of the bank, according to the study.”

OK, so the orange jumpsuit takes evidence beyond a reasonable doubt. But how come the managers of the banks were allowed to keep hundreds of billions in ill-gotten gains, instead of facing civil law claw-backs that required a lower standard of proof? Getting back $200 million from some beneficiary of the real estate and financial instruments frauds — and making a big deal out of it — would have gone a long way to avoiding the Democrats’ electoral disaster in 2010. Even trying (if it couldn’t be played out in two years would have mattered. Same for not wringing hands over the contract law niceties of Wall Street bonuses while labor contracts with the UAW were jettisoned by the administration eagerly.

“There are those who claim that the government’s goal was to protect the banks. I do not share that view, and maintain that instead the government’s goal was to prevent collateral damage from a financial-sector collapse.”

That is a weak, semantic dodge.

The government prevented collateral damage with a failure at General Motors by forcing the management team to resign, wiping out stockholders, and even forcing concessions from labor unions.

But for the financial industry, no one was forced to resign, everyone got their massive bonuses, and everyone who broke (hmm, flouted?) laws were let off the hook with only the most egregious actors earning fines. Worse, no one seemed to spend one single minute debating whether or not to have the Fed stand in for mortgage holders, which could have kept these places solvent (at least on paper) until a more holistic solution could be made. This would have helped home owners (not all of whom were/are bankrupt) while helping the banks. But the Fed chose only to help the banks.

Whether they intended to “protect the banks” or protect others, they treated the banks in a way that no other industry or person is treated. It was very preferential and extraordinarily generous. Your comment is a foolish and silly semantic debate about intentions. The motivations were clear: while auto workers are just a bunch of nose-pickers who needed income hair cuts, the finance industry effectively held “regulators” hostage and were made whole, with virtually no pain or sacrifice. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands lost their homes and/or jobs, paying the price for the industry’s evil.

The FACT is that the banks were protected.

Michael Bloomberg, former Mayor of New York City: “It was not the banks that created the mortgage crisis. It was, plain and simple, Congress who forced everybody to go and give mortgages to people who were on the cusp.”

Ha, ha, ha. That’s hilarious. Congress forced CountryWide to make liar loans? Congress forced JP Morgan to make liar loans? Congress forced Bank of America to make liar loans? To the contrary, these corrupt banks were begging loan originators to get them more loans, forget the paperwork, because they were making money hand over fist packaging and selling fraudulent CDOs.

The corrupt bankers were never held to account for their fraudulent activities. In fact, every time the Justice Department announced a new fine for fraud, bank stocks would leap because stockholders realized that the fines were a laughably trivial portion of their profits. Just the small cost of doing (illegal) business as usual.

It was a public service forcing banks to lend lots of money to low income people.

I’m sure, people like you supported it, before it came crashing down.

PeakTrader: “It was a public service forcing banks to lend lots of money to low income people.”

What the heck are you talking about? How was CountryWide forced to lend to low income people? Did someone hold a gun to their heads? No, they made liar loans because they were getting rich selling them.

Joseph, I’m talking about Congress increasingly facilitating high-risk loans, by government-backed spending, through Fannie and Freddie, the CRA, the FHA, Federal Home Loan Banks, the Veterans Administration and other agencies. Hello?

Why wouldn’t lenders try to make money on this poor policy? Citigroup knew it would end badly, but was forced to lend, because its competitors were making lots of money and it couldn’t fight Congressional pressure to make more risky loans.

You are wrong, Joseph. In fact, this concept has been so thoroughly debunked that it’s shocking to see people clinging to it.

The loans that the government was to underwrite were for conforming loans. The “no doc” and similar predatory loans were NOT part of the program. Although there were some defaults of conforming loans, the majority were non-conforming. Do some homework.

In 2008, over 70% of subprime and other low quality home loans were on the books of government agencies.

Federal agencies not only reduced and relaxed lending standards, they made homeownership easier with more flexible terms.

Consequently, the homeownership rate soared. Of course, many of those homeowners used their homes as ATMs, which eventually created more underwater homes.

“In 2008, over 70% of subprime and other low quality home loans were on the books of government agencies.”

peak, what percentage of the government agency loans went bad to begin the financial crisis? it was not the government agency loans which soured. it was the private sector loans which blew up, and took everything down with them. what is important, and what you refuse to acknowledge, is the private sector loans were the toxic assets that brought down the financial sector. the government did not force the bankers to take on those loans. as a participant in this action, i understand your desire to shift the blame onto others. but bankers such as yourself hold responsibility for what happened. and you should have lost your job for that behavior.

Making things up doesn’t support your case.

The fact is the federal government wanted more homeownership, i.e. marginal borrowers, and Fannie and Freddie became insolvent.

You remain in denial of the tremendous influence the federal government has on the housing market, including influencing people’s behavior.

“You remain in denial of the tremendous influence the federal government has on the housing market, including influencing people’s behavior.”

i fully understand how the government can have an influence. but i also understand businesses, like people, are responsible for their actions. if a business partakes in a certain practice, they are responsible for the risks and outcomes. don’t blame the government for your irresponsible decision making. banks were not forced to make many of these mortgages, they chose that path because they were reaching for yield and did not understand the risk. and they insured those investments without understanding the risks. bankers like yourself, peak, basically screwed up but are unwilling to acknowledge their mistake. just because the speed limit is set at 75 mph does not mean you should meet or exceed the speed limit. slow down at the bend, or take the bend at your own peril. you whine about a government nanny state, but that is exactly what you want to exist so that you can blame the government for your poor financial decision making.

Anyway, you don’t believe the fact that while home prices steadily soared, Fannie and Freddie were required to steadily raise the percentage of home loans it bought or guaranteed for people below medium income to 55%?

Quite a remarkable feat.

timm0, I think you are directing your comments to PeakTrader. Yes, you are right, PeakTrader is simply an apologist for incompetent and corrupt bankers. The sub-prime crisis was created by “financial innovation”, allowing bankers to bundle up and sell garbage loans as AAA-rated CDOs. The Feds had nothing to do with it. Fannie and Freddie didn’t even get into the game until the very end as they were being squeezed out by the big banks. Lenders like CountryWide had nothing to do with CRA.

Sorry, Joseph!

I see subsequent, unsubstantiated blither from peaktrader after my misdirected comment. Quoting garbage data from garbage sources seems to be his/her most “remarkable feat.” Reality threatens small people’s opinions and the result is his/her nonsense.

Thanks Professor Hamilton for calling our attention to an interesting paper. However, I do not find the paper persuasive nor satisfying. There is much to discuss in the paper but I’ll concentrate on two points: 1) the paper gives very short shrift to a key alternative explanation; and 2) So what if the research is valid?

A very obvious alternative explanation, which the authors acknowledge, is that the index put might have a lower price during the crisis because of counterparty credit risk. The put they price is not the standard vulnerable option, whose price must be adjusted for the counterparty risk of the seller (and buyer depending on the nature of the derivative.) The option discussed in the paper is similar to a put option that a counterparty writes on itself. The credit risk of the counterparty and the equity price are correlated. When the equity price falls very low or zero, the counterparty has defaulted and will not pay off the option. Therefore the option itself has very little or no value before the event of default. In the case of the index put considered in the paper, if there is a crisis that affects the entire financial industy, the probability that the option will be paid off in such an event is lower. Hence, the value of the option is lower.

To seriously assess this possibility, it would be necessary to specify a credit-vulnerable put option in which the financial sector index price and the financial sector credit spread are related. The price of such an option will depend on the usual parameters but also on the level of the financial credit spread. The higher the spread, other things equal, the lower the value of the option.

Instead of seriously treating this alternative model, the authors of the paper dismiss the counterparty credit risk explanation by making a series of heuristic but questionable arguments. For example, they argue that because the options are margined daily (among other things) counterparty credit risk is limited. However, it is well known that margin reduces but does not eliminate counterparty credit risk. Jon Gregory’s recent book, Counterparty Credit Risk and Credit Value Adjustment: A Continuing Challenge for Global Financial Markets has much discussion on this point.

The authors also argue that the dynamics of the basket-index spread are not consistent with their interpretation of the meaning of government policy announcements over the period. But in making that argument, they implicitly use a model that they have not estimated, one in which the bailout magnitude is known with certainty but its probability is not. Moreover, the events themselves may be and have been interpreted differently from the intention to do a full scale bail out. Many of the events, for example, have been interpreted as nothing more than a diagnosis at the time that there was a liquidity crisis and government policy should help to provide liquidity in the market. Without a serious treatment of a credit sensitive option as an alternative explanation, it is hard to take seriously that the bail out is the only or even best explanation for the basket index spread.

Even if the paper is right in its conclusions, I still found myself asking “so what?” What are the implications? We must remember that no money was actually transferred to anyone nor did the policy makers pursue this policy in order to “bail out” equity holders. Rather the motivation for the policy, if it did occur, was to avoid an even greater economic calamity that would likely have followed a meltdown of the financial system. If we spent $800 billion on stimulus, given the argument that economic conditions would have been worse had we not, why wouldn’t we create a synthetic instrument with an estimated market value of $282 billion to avoid a depression (with no increase in taxes or borrowing)? By referring instead to the implicit subsidy afforded to equity holders, with its pejorative connotation, many will come away with the view that the policy was ill-considered, although I’m sure that wasn’t the authors’ intention. But even if it was not their intention, that’s how the research will be spun in newspapers and on blog sites. It’s a complex question of course because providing an implicit put does create potential moral hazard and adverse selection problems. But I’d like to know what the authors think their research actually means.

That is very interesting.

Jim says: ”There are those who claim that the government’s goal was to protect the banks. I do not share that view, and maintain that instead the government’s goal was to prevent collateral damage from a financial-sector collapse.”

Collateral damage prevention ? I guess, James does not know Hank Paulson and his motives.

There was political pressure to kill Lehman Brothers. Goldman Sachs and Hank P. are the key to know why. Warren Buffett knew early that Goldman Sachs is under protection, that is why he invested accordingly into GS.

Not only McBride could see this crises coming in 2005. I would rather say this crises was engineered. Paulson, the former assistant to the criminal John Ehrlichman in 1972- that was the place where he learned his trade. Paulson’s net worth has been estimated at over $700 million- James think twice before you suggest an altruistic motive.