Can we fund the partly see-through wall by taxing worker remittances?

Given that tax reform cannot really force Mexico specifically to finance the wall/fence [0], it pays to see what other options are available. One option mentioned by President Trump on the campaign was to impose restrictions on worker remittances back to Mexico.

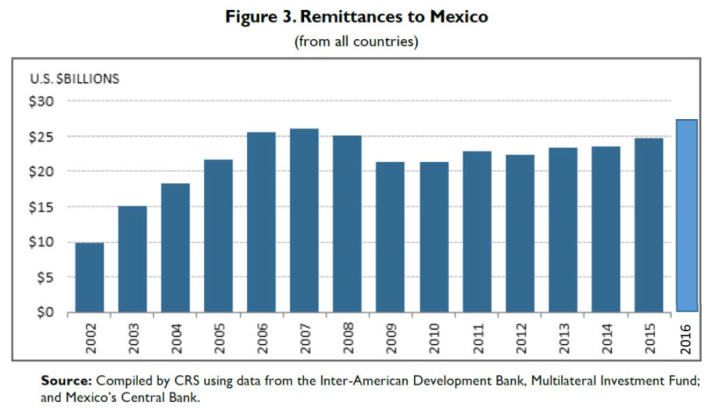

Worker remittances to Mexico were $24.8 billion in 2015 (CRS (2016)) and $27 billion in 2016 [1]). Suppose we applied a 10% tax on such remittances; what would be the impact?

Figure 3 from CRS (2016), modified by author.

There are several reasons why remittance taxes are bad from a general efficiency and development context. However, in terms of the question at hand, here are two particularly salient concerns (from Mohopatra (2010)):

- A remittance tax would also drive these money flows underground. A shift of flows to informal channels can hurt efforts to leverage remittances for increasing access of recipients to formal financial services (financial inclusion) and to raise financing for infrastructure and other development projects …

- Such a tax is difficult to administer as remitters can resort to using informal channels. Also such a tax is highly regressive. And they produce huge deadweight losses as remittances are highly cost-elastic.

How much can a tax on remittances raise? In estimating the revenue gain, a key question surrounds the elasticity of formal sector remittances with respect to the tax. A low estimate of the elasticity of substitution between formal/informal remittances ranges from a low at 4, and a high at 8 (Light and Lewandowski (2015), pp.13-15). Note that this is not an overall remittances elasticity, just that for formal remittances that can be taxed. From Light and Lewandowski (2015):

The elasticity of substitution described here should not be confused with the price-elasticity of demand for remittances overall. The price-elasticity of demand for remittances is the change in total remittance demand compared to a unit change in price. Such an elasticity has been found to be relatively low, less than one. The elasticity of interest here, is the demand elasticity for (taxed) formal remittances only. This elasticity is much higher, because it includes both, the own-price elasticity of demand, plus the elasticity of substitution between alternative methods.

Armed with the relevant parameter, we can now proceed.

Let’s say remittances are $25 billion (assuming the 2016 number was driven by fears of a Trump Administration crackdown), a 10% tax is imposed, and the elasticity is low, then formal remittances decline by 33%, and $1.7 billion in revenue is raised. If instead the elasticity is 8, then formal remittances decline by 55.1%, and $1.1 billion in revenue is raised.

Estimates for the cost of building the wall range from $12 to $40 billlion [2]. This means that it will take some time — well, years — to fund the wall. Of course, there is a maintenance cost associated with the enhanced wall. For extensive details on walls/fences/maintenance costs, see CRS (2009).

Of course, I am not addressing the collateral damage associated with imposing capital controls –- for instance, how much will foreigners want to put their assets in the US if the Trump Administration is willing to impose capital controls (see impact on the Chinn-Ito index discussed here)?

Next part: A Tariff to Fund the Beautiful Wall/Fence

Well, it is more the consequences to immigration to worry about. By sending money home, it keeps more Mexicans from immigrating. On the other hand, that puts tremendous temptation on Mexico to not develop and innovate its economy, as it can rely on remittances, which also encourages immigration. So, it would probably be painful for Mexico in the beginning and increase immigration, but a type of shock therapy in the long run and decrease immigration…

Actually it would be impossible with the spread of debit cards from the US that work in Mexico (but that does require one to have access to the banking system) Prepaid cards do exist also. However the question is more the size of the town the recipient lives in a small town there may be no atms. And of course doing that means the well established Hawala system could move in. (But you would squelch that with money laundering charges)

We need more deterrence to prevent the dangerous trek of entering the U.S. illegally.

Sanctuary cities, for example, is the opposite of deterrence.

Then, we’ll have more money to slow the huge flow of drugs and other more serious criminal activity.

Anyone hiring illegal immigrants should be fined and sent to work camps. Maybe, they can help build the wall for ten cents an hour 🙂

Here are two recent articles of mine related to the topic, on CNBC:

Forget Mexico—Here’s who should pay for the wall

http://www.cnbc.com/2017/01/25/forget-mexico-illegal-immigrants-can-pay-for-the-wall-commentary.html

Op-Ed: How Trump can end illegal immigration right now—without a border wall

http://www.cnbc.com/2017/01/26/trump-can-end-illegal-immigration-without-a-wall-commentary.html

The reaction to these two articles has been genuinely impressive. A good number of people actively looked up my email address to send me comments, almost all supportive, but looking for greater detail.

Indeed, this morning a Hungarian radio station asked for an interview based on these articles. (All my recommendations are essentially derived from my experiences in Hungary, I might add.)

I think there is a genuine hunger out there for a good technical approach to illegal immigration. A lot of Americans are not mean or anti-Mexican, but they want control over illegal immigration. They are also aware that we have to make trade-offs and that there are risks. Very importantly, however, I think people are willing to sign up, but they want to know what they are being asked to do and what they should expect — or not.

I have proposed a solution which treats economic immigration as a business, rather than as a moral crusade. As a business, it is to be run professionally and profitably, with a focus on convenience, speed and certainty to insure compliance.

The proposed program achieves many, but not all, of the objectives of conservative, middle class Americans. The feedback I am receiving suggests Americans are willing to take a business-like approach which neither permits unfettered immigration nor seals the borders hermetically.

Steven Kopits, poor illegal immigrants, who desperately want to improve their lives, shouldn’t be punished, because of the mixed signals they received from U.S. politicians/lawyers.

And you’re wrong about the War on Drugs. The U.S. spends about $20 billion a year to prevent and reduce social costs, which include lost productivity, traffic & work injuries & fatalities, health problems & drug treatment, mental illness, unemployment, crime, domestic violence, child abuse, and other social services. The War on Drugs has saved the U.S. trillions of dollars in social costs. We need to spend more.

Well, here’s a bit on heroin. Why is it ubiquitous? Because it’s cheaper and easier to find that prescription pain killers. Really. The war on drugs has been so successful that illegal drugs are both cheaper and easier to access.

I don’t like that anymore than anyone else, but it’s just ridiculous. After 40 years of the war on drugs, illegal drugs are the low-cost solution. Incredible.

********

From “5 Reasons Prescription Addiction Turns to Heroin”

Heroin Is Cheaper than Pain Pills

Once a person gets hooked on painkillers, he or she is tied into an enormously expensive habit. At anywhere from $60 to $100 per pill, a painkiller addiction is enough to throw one onto hard times financially, especially considering that an addict will normally require several doses per day. Heroin is not cheap, but it is significantly less expensive than painkillers. A single dose of heroin usually costs around $10, depending on the city where it is purchased.

Heroin Is Easier to Find

Prescription painkillers are so widely abused throughout the United States that overdose on pain meds now kills more Americans than both heroin and cocaine combined. With so many people suffering from addiction to these powerful medications, state legislatures, law enforcement and medical regulatory agencies are taking measures to crack down and prevent the drugs from being abused or falling into the wrong hands. One example is the implementation of statewide prescription monitoring programs which keep track of how many painkiller prescriptions that doctors write. This makes it harder for unscrupulous physicians to operate as “pill mills,” selling prescriptions to people who want to get high. The drugs are now significant far more difficult to come by, whereas heroin can easily be found both in the city and the suburbs, provided that one has the right connections.

http://www.narconon.org/blog/heroin-addiction/5-reasons-prescription-addiction-turns-to-heroin/

The point is, Peak, that both drugs and undocumented labor represent a black market. We understand the economics of black markets.

In the case of drugs, there is a reason to resist legalization, notably wide-spread addition.

However, in the case of undocumented labor, on balance I think it makes far more sense to simply charge a gate fee.

addiction is also important.

Steven, you know what will happen if illegal immigration is legalized.

The U.S. War on Drugs has been fought on the supply and demand sides.

Japan has been most successful:

“The Japanese in 1954…inaugurated a system of forced hospitalization for chronic drug users. Under this policy, drug users were rounded up in droves, forced to go through cold-turkey withdrawal and placed in work camps for periods ranging from a few months to several years…This approach to drug users, still in force today, is seen by the Japanese as a humane policy focussed primarily on rehabilitation. By American standards, however, these rehabilitation programs would be seen as very tough.

The Japanese from the very beginning have opted for a cold-turkey drug withdrawal. Thus, every heroin addict identified in Japan is required to enter a hospital or treatment facility, where they go immediately through withdrawal. Conviction through the criminal justice system is not necessary for commitment. Any addict identified, either through examination by physicians or through urine testing, is committed through an administrative process. As a result courts are not burdened with heavy caseloads of drug users, drug users are not saddled with criminal records and punishment for drug users is swift and sure.

The government also launched a substantial public education campaign, including distributing anti-drug messages through government-controlled television movies, radio, newspapers, magazines and books, and posters in airports, railroad stations, bus terminals, and public buildings. Cabinet ministers, governors, mayors and other public officials regularly conducted public forums on the perils of drug use.

These policies dramatically and rapidly cut drug use. Within four years of the 1954 amendments, the number of people arrested for violating the Stimulant Control Law dropped from 55,654 to only 271in 1958.

Japan began experiencing serious problems with heroin. By 1961 it is estimated that there were over 40,000 heroin addicts in Japan…tougher penalties against importation and selling, and by imposing a mandatory rehabilitation regime for addicts.

The results of Japan’s tough heroin program mirrored those of its successful fight against stimulants. The number of arrests for heroin sale and possession fell from a high in 1962 of 2,139 to only 33 in 1966 and have never risen above 100 since.”

Article above from September 24, 1990 Fighting Drugs in Four Countries: Lessons for America?

PeakTrader: Work camps? So… work sets you free?

Menzie Chinn, some people may be happy throwing employers into a work camp or in jail 🙂

I personally think taxing remittances would be quite a challenge. These are intra-personal bank transfers. Would such a tax be on all bank transfers, or only wire transfers via Western Union? If you’re an American retiree living in Acapulco, would that be subject to a remittance tax? The whole approach is not feasible.

Selling visas, of course, is feasible. If you run the numbers, the US is being under-paid for providing access to our labor markets by at least a factor of five. Selling visas should improve the Federal budget, on a net basis, by at least $30 bn per year–more than enough to build the wall.

However, there is no reason to build a wall, just as I argue in my CNBC piece.

steven, selling visa’s would naturally self select the immigrants with a means to enter, and push further way the criteria that their skill set is a necessity.

you need to be sure you have a system that fixes a major flaw in the work visa system as is. currently, many tech companies have too much power over their visa employees, because the employee visa status and green card application is tied directly to the employer. this is a failure in the system. it is why foreign visa workers, on average are paid less than american workers, and also have slower wage increases while employed. i had many friends in this position, and it was terrible. they really were abused in their position, but had no recourse because they could not vote with their feet. it appears there exists abuse of foreign workers both at the low end and the high end.

Steven Kopits Like you, I support massive expansion of legal immigration. But after reading your two articles the conclusion I come to is to ask why you would want to have any entry fee. Okay, I can see a small fee to pay the salaries of State Dept and DHS types who have to process the paperwork just as the State Dept charges US citizens a processing fee for a passport, but that should be a fairly small transaction cost. Imposing any kind of visa fee gets us away from a market based solution because the amount of labor is still determined by the fixed supply curve set by the government. Granted, your supply curve would be much further out than PeakTrader’s, but it’s still not exactly a market based immigration policy. Your article doesn’t make clear if the work visas are annual requirements with the workers going home every year, or if you have in mind a single lifetime fee. The goal shouldn’t be to just let them work here and go home; we also need them to plant roots and raise families.

PeakTrader Sanctuary cities are not just the brainchild of bleeding heart liberals; they are also supported by local police departments for what should be very obvious reasons. Compel local police officers to become ICE agents and you’re going to end up with a lot of dead cops and a lot more gangs.

I see no reason, from the US perspective, not to charge the market rate at equilibrium for access to our labor markets.

Let’s take a more or less realistic case. In Mexico, manual labor earns $2.50. That same labor earns $10 / hour in the US. Let’s assume that living costs are the same and that transportation costs are zero, just for ease of the example.

A Mexican then would be willing to spend up to 3/4 of their time in the US unemployed, and average $2,50 / hour. The US government would see zero revenue. So we’d have lots of unemployed Mexicans and no money. I don’t think you’ll find a lot of Republicans signing up for that. Or alternatively, we can let Mexicans come in until the US manual wage level drops to $2.50 / hour. I don’t think you’ll see a lot of Democrats sign up for that.

On the other hand, if you allow in the equilibrium level of Mexican labor, then all immigrants will be largely fully employed essentially at current wages, around $10 / hour. In this case, however, we have a border arbitrage of $7.50 / hour ($10 / hour in the US minus $2.50 / hour in Mexico), which Mexicans should be willing the pay in its entirety to the US government.

Once you allow for transportation costs and a higher cost of living in the US, you can calculate that Mexicans would be willing to pay $4000-6000 annually to work in the US, compared to $700 in net taxes (ex-Medicare) paid today. Thus, the US is being under-compensated by a factor of at least five, and perhaps as much as a factor of eight, for access to its labor markets.

People get that. They want the undocumented population to be documented, and they want to be paid for providing access. And they want to be able to quickly remove criminal immigrants as necessary. I am guessing they will be more forgiving on the total headcount. The system I am proposing is only effective around the market equilibrium. Compliance is only effective when it accounts for market realities.

And by the way, you’d eliminate sanctuary cities at a stroke.

Steven Kopits I think you misunderstood my point. What you’re describing is not a competitive market solution. What you’re describing is a rent extraction scheme, with the surplus going to the US Treasury. That’s because your model still has the US government determining the number of visas granted; i.e., the US government is controlling the supply. I agree that a lot of Republicans might like that kind of arrangement, and I would even agree that it would be a big improvement over the current system. And light years better than building some stupid wall. But a truly competitive market solution would allow for the (nearly) free movement of labor across the borders without the government extracting rents. You’re from Hungary so you might appreciate the analogy. Back in medieval times various lords would establish castles along the Danube and extract rents from traders going up and down the river. That’s essentially what you’re wanting the US government to do. Yes, it would generate revenue for the Treasury just as it generated revenue for the Hapsburgs, but rent extraction stifles economic growth. But I will say that your approach has the merit of being adult, which is a lot more than can be said about Trump’s wall nonsense.

Yes, indeed, I am doing my best to make work-related immigration a profit center.

You do need an authorizing body at the top, that’s true, and it’s also true that it is the trickiest part of program design.

I would probably prefer that the Fed actually operate the system, balancing visa price, quantity and wages received. This is really a technical function something between open market operations and optimizing the price of airline seats. You do, however, need an authorizing body above that level, and the composition and rights of that body bears some serious reflection.

In the initial go, I would doubt that Congress would permit the issuance of visas with a term greater than one year–and that’s fine, It would take some time to optimize the range of variables associated with system operation. But it’s something the Fed already knows how to do in a different market, eg, treasuries.

As for a path towards citizenship, this program does not provide it. But to the extent that participants believe that it does, it will be reflected in the market value of the visas. If citizenship is part of it, that will also be sold at market value.

Now, were that to happen, the whole market will go crazy, because the price of the visa will exceed the annual wages to be earned, and that would be both instantly visible on the market (these are traded securities) and accompanied by howls from employers. Thus, as the market for treasuries, the system would have certain self-correcting tendencies.

Thus, we’re left with four options:

1. Do nothing. In this case, we do not change the exiting number of undocumented immigrants, they remain undocumented, and are joined by more coming over the border.

2. Build a wall. This is incredibly expensive, unlikely to work (see the bit on the heroin market above) and does absolutely nothing with immigrants already here.

3. Build a wall and deport people. The Arizona experience suggests this is a viable strategy, at least in part. It will also cost a bundle, trash the US ag sector, and more or less bring civil war to the streets.

4. Let immigrants comes and go as they please, but at a fee priced at the market clearing level. This would end non-crime related illegal immigration immediately without a wall; document the vast number of illegals in the country and provide them status; spare the lives of some 500 migrants who die trying to enter the US annually; and swing the Federal budget by at least $50 bn compared to building a wall.

The decision here is not even close. Not by an order of magnitude.

2slugbait, they’re supported by the mayors and police chiefs – the political class – not, by and large, the rank & file, police unions, and sheriffs.

Beyond the wall there is the threat of sending the armed forces into Mexico to go after the “Bad Hombres”!! Shades of Pancho Villa and Gen. Black Jack Pershing. Some time around the 1911 revolutions.

Dean Baker had an interesting response by Mexico:

http://cepr.net/blogs/beat-the-press/a-trade-war-everyone-can-win

While the economic discussion of dealing with ah, informal, immigration is worthwhile (and given this blog, a given), it has to be salted with the social dynamics of American nativism.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 made absolutely no economic sense, but was widely popular, regardless. The core prejudices that informed that popularity have changed only very moderately since then. When it comes to issues like immigration and its economic effects, people are cough irrational players.

I would argue that the most relevant socio-economic text on the subject (and for this calumnious era in general) currently is “The True Believer: Thoughts On The Nature Of Mass Movements”, by Eric Hoffer.

SecondLook: I agree on the motivation, see here. Haven’t read the book you mentioned, am reading Shirer’s Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, which seems relevant.

Read this book ages ago for some seminar:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crowds_and_Power

Knocked me on my butt. To this day I can’t look at a politician’s clenched teeth without being reminded of this book.

The U.S. has more immigrants than any other country. About 15% of the population are legal immigrants. I wonder how many immigrants China has?

http://m.scmp.com/news/china/article/1272959/under-chinas-new-immigration-law-harsher-fines-illegal-foreigners

Latest I’ve seen is 13%, the highest since the 1920s and just off the all-time peak around 14% (for the last 150 years).

I think there’s a case for slowing it down and digesting a bit, certainly from a societal perspective. On the other hand, if you want to fund pre-existing conditions and save Obamacare, well, you better start coming up with some other bright ideas.