National Trade Council Director Peter Navarro writes in the WSJ:

The national-security argument that trade deficits matter begins with this accounting identity: Any deficit in the current account caused by imbalanced trade must be offset by a surplus in the capital account, meaning foreign investment in the U.S.

… running large and persistent trade deficits also facilitates a pattern of wealth transfers offshore. Warren Buffett refers to this as “conquest by purchase” and warns that foreigners will eventually own so much of the U.S. that Americans will wind up working longer hours just to eat and to service the debt.

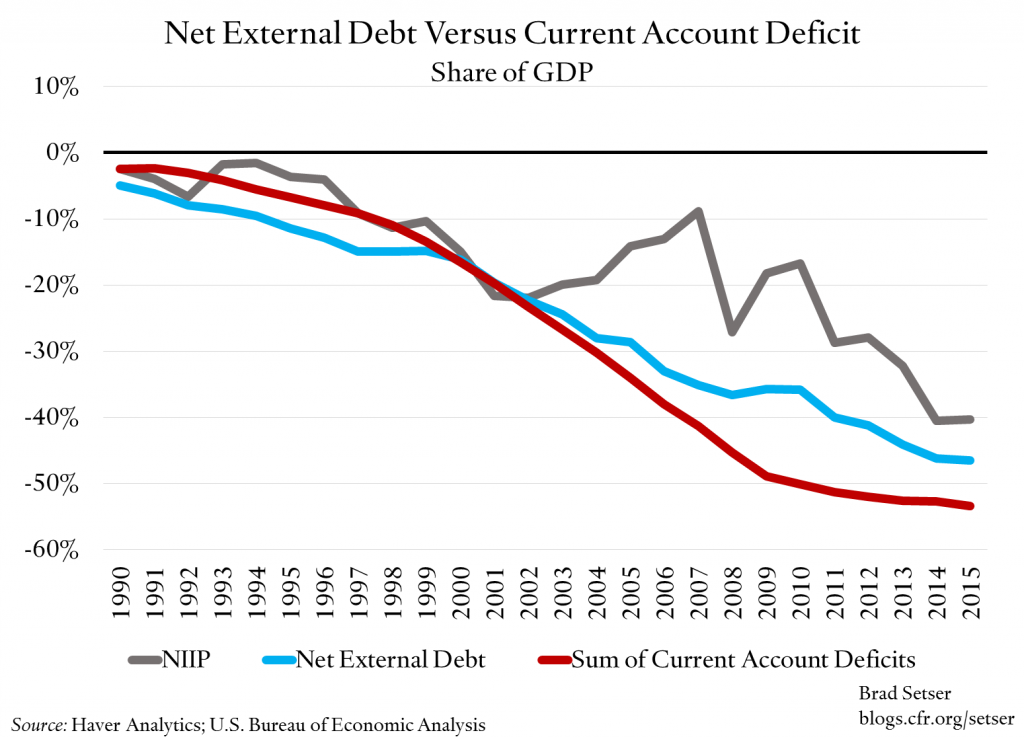

I’ve made a similar argument before, particularly in the context of how the current account deficits of the mid-2000’s were driven by the tax cuts and unfunded wars (and hence budget deficits) of the G.W. Bush Administrations [1]. However, there is an important caveat — and that is that the net international investment position does not move in lockstep with the cumulative current account imbalance. This is shown in this Figure reproduced from Brad Setser:

Source: Setser, “Dark Matter. Soon to be revealed?” Follow the Money, February 2, 2017.

The gap is driven by various factors, including exchange rate changes, but also valuation changes of FDI. So far, the gap has amounted to a not-inconsequential 10% of GDP as of 2015.

None of this should be taken to mean that we shouldn’t be concerned about the deteriorating net international investment position. However, changes in relative prices of imports and exports by virtue of tariffs against specific countries are unlikely to change the current account balance, which is largely driven by private saving vs. investment flows, and the government’s net saving (i.e., inverse of budget deficits). My guess is that a CBO score of the President’s budget — when it comes out — is unlikely to show a reduction in the full employment budget balance.

If I were thinking about national security, I might be more concerned about the destabilizing impact of aggressive trade actions on our allies’ economies (including those of Mexico and the NATO nations).

I don’t get how the “deficit in the current account caused by imbalanced trade must be offset by a surplus in the capital account, meaning foreign investment in the U.S”. How does this happen without leaving the ROW short on dollars (Triffin Dilemma)?

What if China uses a billion of its surplus dollars to buy oil, and then the Saudis use those dollars to buy camel feed, and then the nation that produces camel feed buys fertilizer from some other nation, and so and so on, with some dollars never repatriating?

Anyway, I understand that this accounting identity claim exists in the world of text books and oversimplifications, but it seems that dollars not only can remain out in the world indefinitely, but dollars must remain coursing through the global economy and increasing in step with global growth.

How about the thrillions stashed away in oversea subsidiaries of US companies.

The following is from an article on the Fx by Tim Taylor:

“The headline finding is that the total turnover in foreign exchange markets dipped from $5.4 trillion per day in the 2013 survey to $5.1 trillion per day in 2016. As the figure shows, there had been a dramatic rise in the volume of foreign exchange trading since about 2000, so the dip is especially notable.”

Yea, that is $5.1 TRILLION worth of currencies PER DAY!!!!! And the dollar makes up 44% of that PER DAY!!! So how is it possible that the US trade deficit of $500 billion becomes “a surplus in the capital account” with so many other dollars in play in the global economy?

Income Flows from U.S. Foreign Assets and Liabilities

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

November 14, 2012

Foreign investors placed roughly $1.0 trillion in U.S. assets in 2011, pushing the total value of their claims on the United States to $20.6 trillion. Over the same period, U.S. investors placed $0.5 trillion abroad, bringing total U.S. holdings of foreign assets to $16.4 trillion. One might expect that the large gap of -$4.2 trillion between U.S. assets and liabilities would come with a substantial servicing burden. Yet U.S. income receipts easily exceed payments abroad.

As we explain in this post, a key reason is that foreign investments in the United States are weighted toward interest-bearing assets currently paying a low rate of return while U.S. investments abroad are weighted toward multinationals’ foreign operations and other corporate claims earning a much higher rate of return.

U.S. investors earned a much higher rate of return on multinationals’ foreign operations and similar corporate holdings than did foreign investors here, 10.7 percent versus 5.8 percent, respectively.

The superior U.S. rate of return on FDI, as well as the greater tilt in U.S. foreign investments toward FDI, accounts for the $322 billion income surplus recorded in this category in 2011…The United States has earned a substantial premium on FDI investments at least since the 1960s.

“…current account deficits of the mid-2000’s were driven by the tax cuts and unfunded wars (and hence budget deficits) of the G.W. Bush Administration.”

I think, that explains only part of it. Reagan cut taxes and increased spending on the military. It was also driven, in the 2000s, by more offshoring and the housing bubble getting bigger.

“…changes in relative prices of imports and exports by virtue of tariffs against specific countries are unlikely to change the current account balance, which is largely driven by private saving vs. investment flows…”

So does a current account deficit cause (result in) net capital inflows, or do net capital inflows cause (result in) a current-account deficit? I’ve seen it argued both ways but am not aware of the consensus view.

BTW, what was once known as the capital account is now known as the financial account. The capital account still exists but it is very small (at least for the U.S.) and consists primarily of cross-border transactions in non-produced non-financial assets.

It is very simple, the current account deficit will equal the domestic savings-investment gap because two prices change to bring this balance into being. The two prices are the currency and interest rates, and to be more exact interest rate spreads.

Look at what happened when Reagan massively cut taxes and created the large structural deficit that Republican tax cuts have repeatedly produced. The dollar soared as largely Japanese capital flowed in to finance the domestic savings-investment gap. The soaring dollar in turn created a very large current account that offset the saving-investment gap. Remember,the consensus was that the Reagan deficit would cause rates to soar and crowd out domestic investment. At that time consensus economics only looked at the US economy as a closed system and did not consider that foreign capital would flow in to finance the Reagan deficit. They were right that we would have crowding out, but it worked trough the strong dollar not though higher rates and damaged the economic sectors most exposed to foreign competition rather than the interest sensitive sectors.

The bottom line is what killed all the jobs in US manufacturing was the Republican tax cuts and it looks like we are about to repeat the same mistake. I wonder what Trump and the republicans will do in a couple of years when we actually have a larger trade deficit than now. It will be interesting.

There may be some reshoring from a lower corporate tax rate and fewer regulations, which will also prevent some offshoring. There may be boom in fossil fuels production, and we may import less oil, particularly with stronger growth. There may be less government spending on the unemployed, and taxes can be raised when a real recovery is underway.

What killed manufacturing jobs was offshoring production, including entire industries, importing those goods at lower prices and higher profits, and employing the freed-up resources in other segments of the economy, including shifting into high-end manufacturing and retail from increased consumption. There were huge productivity gains in manufacturing. Foreign countries had more pro-business policies that facilitated offshoring, like China’s “growth at any cost” (which was very high).

Spencer, stronger economic growth results in higher interest rates and a stronger dollar.