Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Swarnali Ahmed Hannan, economist at the IMF. The views expressed herein are those of the author and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.

In a recent IMF working paper entitled “Revisiting Determinants of Capital Flows to Emerging Markets—A Survey of the Evolving Literature”, I recount a roller coaster ride into the history of the determinants of capital flows to Emerging and Developing Market Economies (EMDEs).

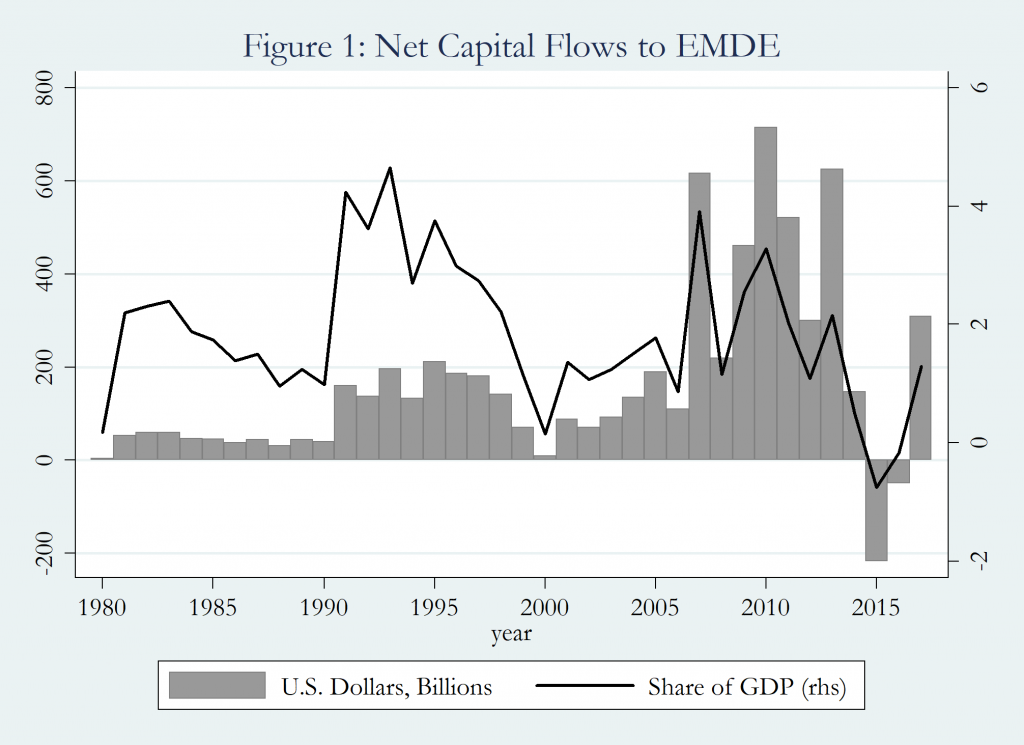

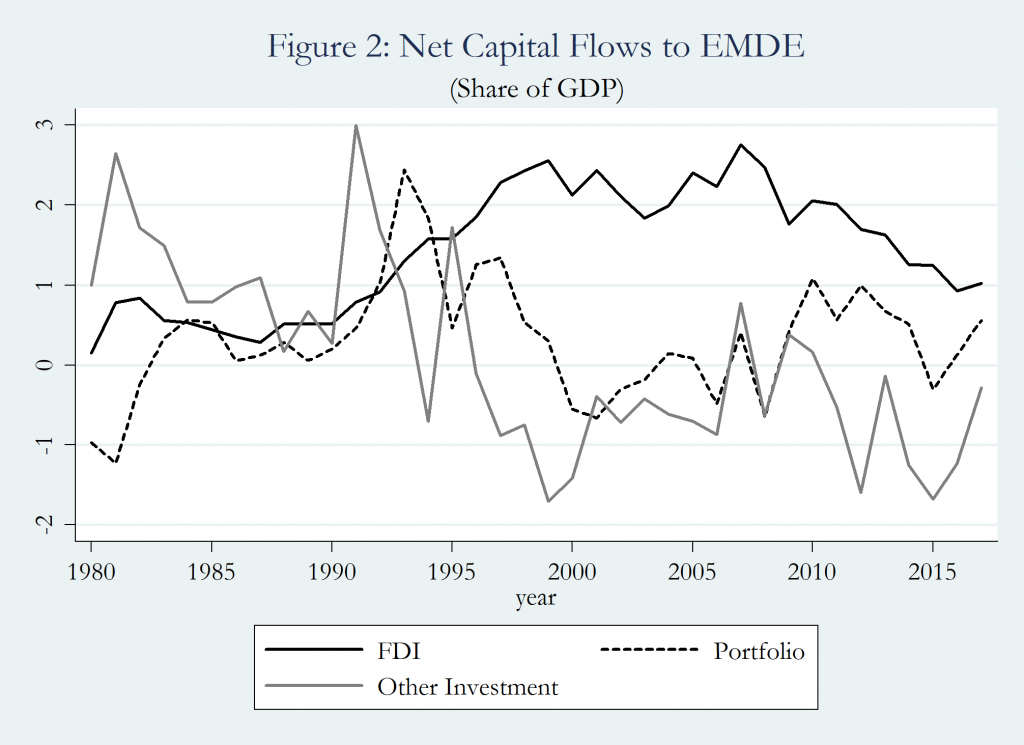

Although the capital flow landscape has changed immensely over the past four decades in terms of both magnitude (Figure1) and composition (Figure 2), the million-dollar question has remained the same: are flows to EMDEs driven by push or pull factors? The former represents external conditions that underpin the supply of global liquidity (e.g. global interest rates, global risk aversion, global commodity prices), while the latter reflects domestic characteristics in EMDEs (e.g. domestic growth, domestic interest rates). An important caveat is, of course, that these two factors cannot always be separated. Often, the international investor response could arise through an interaction of both country-specific and global developments.

The capital inflow surges of the 1990s—Is it push or pull?

The seed of the push versus pull debate was planted following the post-Latin American debt crisis rebound of the flows in the 1990s.

An IMF (1993) review of capital inflow surges concluded that domestic factors were the main drivers for these episodes, on grounds that: (i) the timing of the surges did not coincide with the timing of the changes in the external factors; and (ii) the timing, persistence and intensity of the surges varied across countries.

When the conventional wisdom was that domestic factors were the main drivers of capital inflows, seminal work by Calvo et. al (1993) tilted the scale heavily towards the predominance of external factors. Based on the simple observation that capital was returning to most Latin American countries at the same time, they argued that domestic policies alone could not be the prime driver of flows since there were striking differences in macroeconomic policies and economic performance across these countries. Rapid inflows were instead driven by a set of common external factors, including: (i) the sharp drop in U.S. short-term interest rates; (ii) the prolonged recession in the U.S. and other advanced economies; (iii) the sharp swings in the private capital account of the U.S. balance of payments; and (iv) the regulatory changes that decreased transaction costs related to international capital markets.

The subsequent literature—using different econometric techniques and data—either supported the relative importance of the external factors (Fernandez-Arias 1996, Taylor and Sarno 1997) or refuted that claim (Chuhan, Claessens and Mamingi 1998, World Bank 1997, Ghosh and Ostry 1993).

The early 2000 to pre-crisis era—The devil lies in the details

With the availability of more granular data and rapid trade and financial integration, the push versus pull debate focused on the determinants of specific components of capital flows, summarized in Koepke (2015).

Albuquerque et. al (2005) found evidence that the rapid increase in foreign direct investment (FDI) flows could be attributed to increased integration of world capital markets following the reforms and liberalization efforts of the mid-1980s and 1990s. Domestic factors (e.g. productivity growth, trade openness, financial depth) were becoming less important in explaining the variation in FDI.

Interestingly, the importance of push factors differed across EMDE regions, with them playing a bigger role for portfolio flows to Emerging Asia than to Latin America (Baek, 2006). Similarly, different domestic drivers affected the type of flows differently. De Vita and Kyaw (2008) found that productivity growth were more determinants for FDI flows, while domestic monetary conditions were the predominant driver of portfolio flows.

Along came the crisis—Let’s start all over again

The capital flow landscape has changed remarkably since the global financial crisis (GFC). While the pre-crisis era was marked by a gradual (and, sometimes, a rapid) rise in capital flows owing to financial integration and strong growth prospects in EMDEs, capital flows dropped sharply following the crisis, briefly surged and then slowed down in the period 2011-2016.

The introspection…

Fratzscher (2012) analyzed the causes of the 2008 collapse and the subsequent surge in global capital flows. Unsurprisingly, the key crisis events and global liquidity and risk profiles were found to be the main determinants of the capital flow swings, although the effects were highly heterogeneous across countries. This heterogeneity reflected domestic factors like quality of domestic institutions, country risk, and the strength of domestic macroeconomic fundamentals.

Similar conclusions were found by IMF (2014), which studied capital flow behavior in EMDEs following the 2013 taper tantrum episode. While asset prices and capital flows were indiscriminately hit across countries during the initial periods following the Fed’s announcement, over time there was increased differentiation depending on the domestic characteristics.

…and the retrospection.

The literature continues to add further nuances to the push/pull debate and highlight the new features of the evolving capital flow landscape. Ghosh et. al (2014) showed that global factors determine the time of capital flow surges, however the incidence and the magnitude of these surges depends on domestic factors. Forbes and Warnock (2012) found that the determinants of gross capital flows, be it gross inflows or gross outflows, were considerably different from those of net flows, which was the main focus of earlier literature. Ahmed and Zlate (2014) found significant changes in the behavior of net capital inflows since the GFC, particularly for net portfolio inflows, given the greater sensitivity of such flows to interest rate differentials. Specifically, they argue that unconventional monetary policy in advanced economies has had positive effects on overall capital inflows to EMDEs, with the effects being larger for portfolio flows as well as gross inflows.

Both push and pull factors matter. The debate on the relative importance continues…

The relative importance of push versus pull factors is likely to continue to be a central theme of the capital flows literature. Future research will likely continue to take a more nuanced and granular approach, both in terms of the type of flows as well as circumstances that determine whether pull or push factors matter more. In particular, there is a need to better understand the cyclical versus structural factors responsible for capital flows, the impact of external factors on FDI, and its changing nature; and how the capital flows differ for advanced economies compared to EMDEs.

References

Albuquerque, R, L Norman, and L Serven (2005) “World Market Integration through the Lens of Foreign Direct Investors,” Journal of International Economics, 66(2), 267–295.

Baek, I (2006) “Portfolio Investment Flows to Asia and Latin America: Pull, Push or Market Sentiment?” Journal of Asian Economics, 17(2), 363–373.

Calvo GA, L Leiderman, and CM Reinhart (1993) “Capital Inflows and Real Exchange Rate Appreciation in Latin America: the Role of External Factors,” IMF Staff Papers: 108–151.

Chuhan, P, S Claessens, and N Mamingi (1998) “Equity and bond flows to Latin America and Asia: the role of global and country factors,” Journal of Development Economies, 55, 439–463.

De Vita, G, and KS Kyaw (2008) “Determinants of Capital Flows to Developing Countries: a Structural VAR Analysis,” Journal of Economics Studies, 35(4), 304–322.

Fernandez-Arias, E (1996) “The New Wave of Private Capital Inflows: Push or Pull?” Journal of Development Economies, 48(2), 389–418.

Forbes, KJ and FE Warnock (2012) “Capital flow waves: surges, stops, flight, and retrenchment,” Journal of International Economics, 88(2), 235–251.

Fratzscher, M (2012) “Capital Flows, Push versus Pull Factors and the Global Financial Crisis,” Journal of International Economics, 88(2), 341–356.

Ghosh, AR, MS Qureshi, J Kim, and J Zalduendo (2014) “Surges,” Journal of International Economics, 92(2), 266–285.

Ghosh, AR and JD Ostry (1993) “Do Capital Flows Reflect Economic Fundamentals in Developing Countries?” IMF Working Paper No. 93/34 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Hannan, SA (2018), “Revisiting the Determinants of Capital Flows to Emerging Markets—A Survey of the Evolving Literature,” IMF Working Paper No. 18/214 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

IMF (2014) “Emerging Market Volatility: Lessons from the Taper Tantrum,” IMF Staff Discussion Note (Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund).

IMF (1993) “Recent Experiences with Surges in Capital Inflows,” Occasional Paper No. 108. (Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund).

Koepke, R (2015) ”What Drives Capital Flows to Emerging Markets? A Survey of the Empirical Literature,” (Washington, D.C.: Institute of International Finance).

Taylor, MP and L Sarno (1997) “Capital Flows to Developing Countries: Long-and Short-Term Determinants,” The World Bank Economic Review, 11(3), 451–470.

World Bank (1997) “Private Capital Flows to Developing Countries: the Road to Financial Integration,” World Bank Policy Research Report (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

This post written by Swarnali Ahmed Hannan.

I know this horse has been beaten to death, but at least his take on it is relatively up-to-date.

https://www.creditwritedowns.com/p/the-european-union-may-not-survive

Europe is STILL shifting to the right. Steve Bannon wandering around Europe, feeding off it like a parasite sucking on the wounds of a dying man. It’s still a dangerous situation. I’m not sure if people are anticipating enough “What happens if Putin invades Ukraine?” or people are just too afraid to speak it out loud.

One interesting question going forward is to what extent, and how, macroprudential policies modulate the push and pull factors.

One of the many reasons I like reading stuff like this, and why we are so fortunate Professor Chinn has “the pull” to get people like Mr. Ahmed Hannan on (see what I did there??), is learning new and useful terminology. I’ve read a decent amount of these papers, and that terminology (pull, push) is new to me (obviously because my knowledge base is lower than you two gentlemen).

This paper is a nice contribution to the literature, and I hope Mr. Ahmed Hannan doesn’t take the quiet response by the blog in a negative way. That is my/our downfall as it takes me some time to digest and metabolize these papers into my brain. I want to give the paper it’s proper due and ask intelligent questions and make intelligent comments, and not “slough it off” talking about something when I haven’t read ALL of it or taken it all in. If this post keeps the comments open for roughly the next 14 days, I hope to make some intelligent comments or questions on it. The paper is appreciated. These things are appreciated even though that fact may not always be communicated properly to academics.

Great post. Another question:

Can we do long-term events study of productivity, (in)equality, political/economic/societal/legal institutions or anything of that sort?

About halfway through the article. Did a search for this and thought it was interesting. I assume these would be the areas of focus for the latest research??

https://www.gfmag.com/magazine/april-2018/alchemy-fdi

I like this paper a lot because it’s pretty suitable to my level of knowledge (although I think I am capable of more difficult papers, this hit my goldilocks “this porridge is just right” spot) It gives a nice broad overview and didn’t have much greek symbols which tend to muddle my brain. That’s more of a criticism of myself probably than necessarily a compliment to the difficulty level of the paper–although again, I found it breezy (as in enjoyable) reading once I got into it.

There are many thought trains one can go down through in this paper, which I am sure if I wanted I could come up with 15–20 observations and questions pretty easily, China hits my mind a lot on this, as does Singapore and East Europe (in terms of questions and observations).

I guess the one observation I would make (and if I am just regurgitating Mr Hannan’s thoughts I hope he will give me a pass) is that I think when global risk is very high, then pull factors would start to dominate. And if global risks are very low then the push factors would start to dominate. I also think that certainly 20 years ago China, Vietnam, North Korea, and maybe some others would have been inoculated from a lot of “push” factors, this due to the capital controls in that region at that time. I think this is STILL the case in 2019, although to a much lesser degree. And I think if we look at the South European crisis, it seems like bond/credit flows had a much bigger impact and ability to tip the scales on things, than equities markets, which as a person who has been more consumed with following equities markets than credit markets, was quite a bewildering spectacle, though in a jaded way, kind of fun to watch.