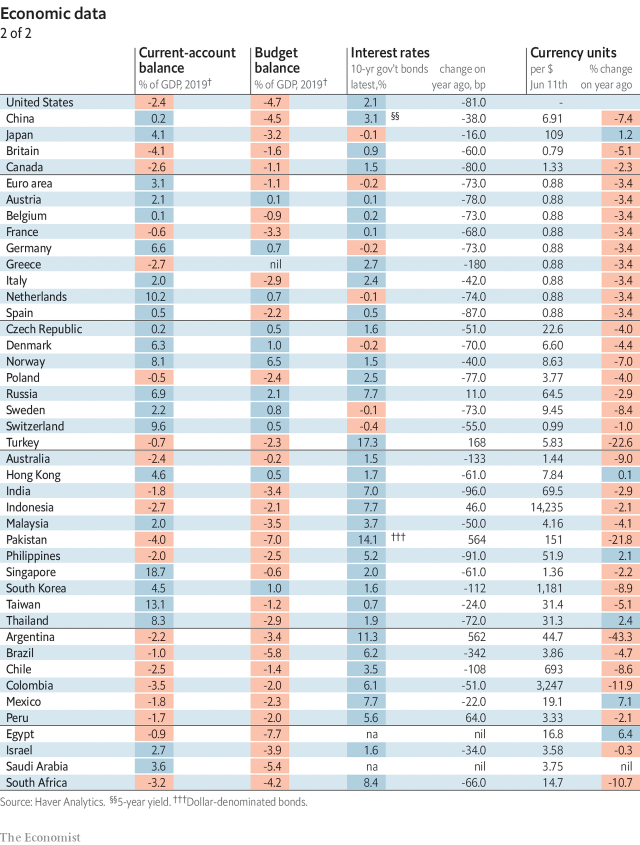

Perusing the last issue of the Economist, I noted that among advanced economies, only Greece (180 bps), Spain (87 bps), Australia (133 bps), South Korea (112 bps) and Chile (108 bps) had larger declines in the ten year yields than the US (81 bps).

Of these, one could argue Greece and Spain declines were attributable to a decline in default risk, leaving only Australia, South Korea and Chile.

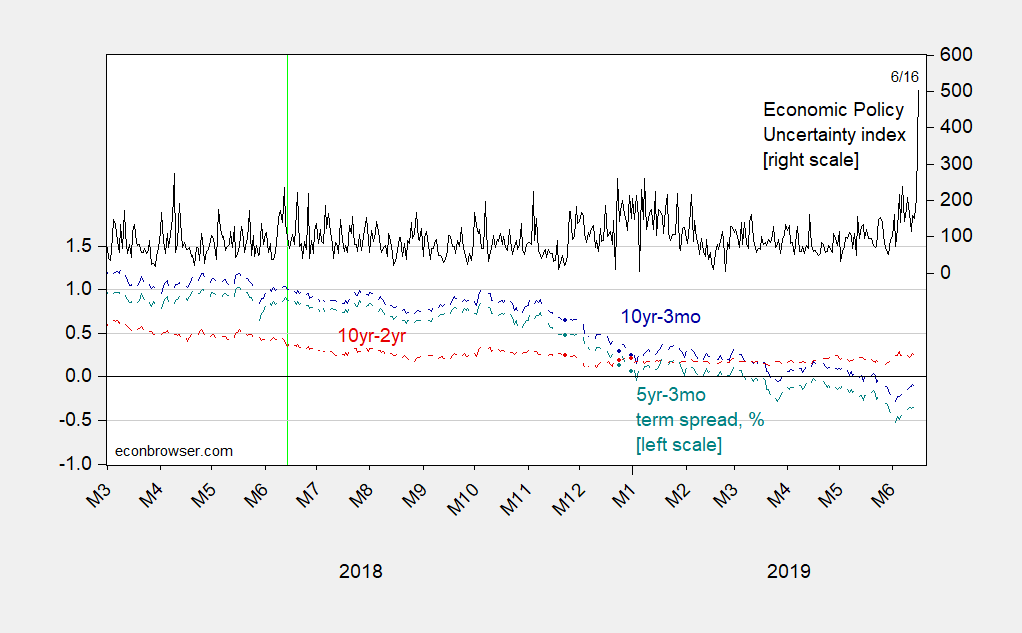

Figure 1 below illustrates what has happened to 10yr-3mo, 10yr-2yr and 5yr-3mo spreads over the past year (indicated by vertical green line)

bye bye inflation.

As we know only too well down under Central Banks can reduce inflation very easily but cannot raise inflation very well

@ Not Trampis

I’m speaking more to America than I am Australia, as I do not know exactly what Australian’s situation is. I suspect it’s similar, but I do not know. But when I look at America I see larger amounts unemployed than is recognized by official numbers. I see large numbers of people making a minimum wage which is not a working wage. Now can you have inflation in countries where the general population is “piss poor”?? Yes you can, the cliche example is Weimar Germany. Currently you have Venezuela and it seems Argentina can’t even go 5 years without have some kind of inflation melodrama. Brazil has had spouts. So, yes we know it’s possible to have inflation where large amounts of people are poor. But I would argue it’s much harder to have inflation when large numbers of people can’t even subsist. So….. I would agree with you, disinflation would be the bigger issue here. No raise in wages at the same time you have glacially slow rises in prices. Speaking just to America here, and in a general way. That doesn’t mean there aren’t sectors or regions in America where usury is still practiced or price gauging doesn’t occur, just speaking broadly.

*In the above comment, when I said “working wage” I should have said living wage, although arguably both terms apply.

we have a large number of underemployed so there are lots of part-times who wish to be full-timers.

Given the demise of unions I am wondering whether we shall ever see wages rise to spike inflationary expectations again.

Do not worry folks. The US federal reserve will contract some Canadian beavers to work on ramping up inflation rates. Though I reckon dynamiting the US economy would get US inflation rates higher than just Canadian beavers using artesanal tools.

I am very disappointed that all those well paid economists beavering away in the Fed’s regional banks have not not understood that Trump’s great vision for the US economy is by far the very best way of ramping up inflation. Autarky is THE path to higher inflation rates. Moreover, US Federal Reserve economists share a common culture with President Trump — the culture of benevolent deception.

Erik,

Is this more fake news Trumpshit paranoia? I challenge you to provide a single instance, even one, of regional Fed economists engaging in “benevolent deception.” As it is, Trump certainly does engage in deception, closing on 11,000 public lies since his inauguration, but I am hard pressed to see any of it as “benevolent.”

Barkley Rosser: Why has the US Federal Reserve not reduced the inflation target to let’s say 0-1% with a long term goal to reset the inflation target at 0% with -0.5% to +0.5% range?

Why are positive and higher inflation rates viewed as a positive for the US economy? Why is enhancing relative price confusion viewed as a positive?

Why is stable low deflation viewed as negative when the historical evidence suggests the opposite despite the misinterpreted n=1 example from the Great Depression?

Why are regional Fed chairs such as Bullard still talking about engineering higher inflation rates? Why, when this century has witnessed massive central bank stimulation with little or no impact on measured inflation and inflation expectations?

I would respectively that suggest American economists stop trying to con people.

And yes, if you can come up with good reasons as to why enhanced relative real versus nominal price confusion is good for the economy, then I suggest you undertake policy to move the US economy in a direction of increased autarky. Trump’s narrowly focused, myopic patriotic nationalism is your best shot. As for the rest of confidence-crushing policies and rhetoric, if capital starts to flow out of the USA and the US dollar decreases, measured inflation will go up.

One could also characterize Trump’s policies as ones that will inevitably erode US human capital and social capital. Presumably, this will ultimately negatively impact US productivity growth, another positive for those seeking higher inflation rates, at least according to models developed in the 20th century.

Erik Poole: Perhaps I’m misunderstanding your argument, but most economists believe a little inflation which prevents unanticipated debt deflation is a plus, given the asymmetric impacts on creditors vs debtors.

Menzie Chinn: So if I understand you correctly, anticipated changes in inflation or deflation should have no impacts on debtors.

Let’s go back and think about unanticipated changes inflation. Suppose measured inflation starts at 2% at the beginning of the debt contract and ends at 1% at the end of the same contract. Creditors win and debtors lose assuming that the growth rate of debtor income declined by the same amount as the inflation rate.

How is a similar unanticipated change in inflation from let’s say +0.5% to -0.5% going to result in an outcome that is fundamentally different?

If wealth distribution is a priority, I would suggest that a policy rate of zero percent inflation would benefit financially unsophisticated folks who store what little wealth they have in boxes and holes in the ground. Bona fide poor folks tend to lack the financial skills that would enable them to gain from inflation or at the very least off-set it.

If bad financial choices and horrible personal consequences are a concern, then maybe teaching or somehow persuading people not to use credit cards to advance discretionary consumption items would be worthwhile. No matter how tough.

People have to learn to play together better, they have to learn how to co-operate better in both business and political environments. Citizens are constantly turning to Central Banks to resolve problems they are generally incapable of resolving: structural unemployment, deteriorating public infrastructure, expensive and risky foreign policy, special-interest rent seeking, income distribution, etc.

For the US central bank: Drop the employment mandate, set the inflation target at 0%, assure financial asset stability and then get out of the way so citizens are encouraged to focus on better, more appropriate tools for the public policy challenges they face. This is probably good advice for all the other rich-country OECD members too. Some of them may no longer have an explicit employment mandate but they behave like they still have one.

Collateral constraints due to asymmetric information implies negative inflation surprises are not neutral. We teach this in undergrad finance.