Once one takes into account spillover effects, which are likely to be large in the Eurozone

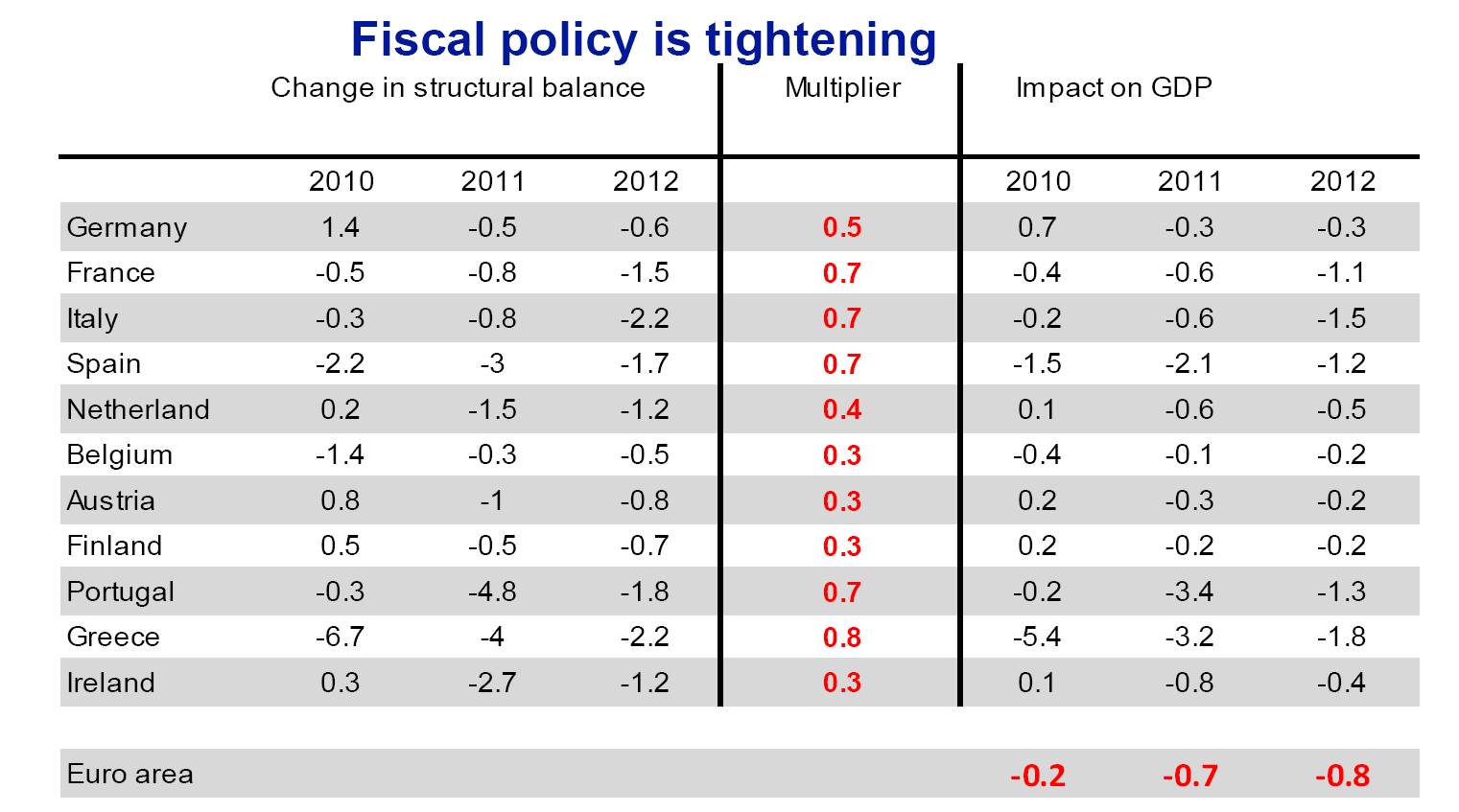

In my post from last week in which I made the commonsensical observation that contractionary fiscal policy is contraction, I reproduced this table from a Deutsche Bank publication.

Figure 1: Fiscal adjustment, multipliers, growth impacts. Source: Deutsche Bank, “Fighting the Clock,” Fixed Income (May 2012) [not online], Note: a negative sign under “change in structural balance” indicates an increase in the surplus.

In a personal communication, Not the Treasury View’s Jonathan Portes observed that the multipliers, and associated impact on the eurozone, would be larger once one takes into the spillover effects, as closely linked countries embark on fiscal contraction (see this Vox post). Another communication from NIESR’s Dawn Holland indicates that treating the eurozone as a single economy implies the weighted average should be increased by about 30%. NIESR’s macroeconometric model, NiGEM, [1] suggests the individual standard country multipliers should be adjusted upward by different amounts (the NIESR’s NiGEM multipliers are likely to be different than DB’s).

Figure 2: Multiplier adjustment factor, accounting for spillover effects. Source: D. Holland.

The logic is as follows. The standard multiplier assumes each country can be treated as a relatively small open economy, where decreases in output induce decreases in imports, which offset the initial decline. However, when all countries are simultaneously shrinking, then the decline in imports is in turn mitigated.

Thinking about the eurozone in terms of individual countries highlights the fact even if some countries are constrained by borrowing costs (compare against the US Federal government with current real funding rates of zero), Germany and other northern European could stimulate their economies. This would help brake the continent’s contractionary spiral.

Personally, given my skepticism regarding the rapidity with which new institutional arrangements such as a banking union can be effected, unilateral measures by eurozone countries with fiscal space seem more plausible means of staving off a full-fledged financial crisis (as well as by the ECB, as discussed here).

The change in GDP is smaller than the change in stuctural balance.

That’s exactly what we want.

The decline in GDP is due to the accounting identity.

The private sector growth rate is bigger and the long term growth rate. To maintaing the previous GDP growth through spending, they would have to borrow more than they grow GDP every year and the amount borrowed to maintain that growth would increase.

What is quite remarkable is that most of spending is done by borrowing, so all the money doesn’t go to the private sector (if it was financed by taxes, the money would all go into the private sector).

What is important is that the private sector growth rate increases.

What is the nominal GDP growth over debt growth?

What is private sector growth over debt growth?

Gee, if we could only nationalize ALL private assets, then the government could dole out what it thinks is appropriate to everyone’s needs and no one would have to worry about a monetary crisis or inflation or protecting their assets or anything. We’d all be taken care of and none of those other messy currencies would affect us.

I wonder what the multiplier effect of all that would be?

So, let’s say the multiplier is .5.

In year 0, a billion dollar construction effort increases GDP by .5 billion.

Next, we need to subtract out the NPV of the cash flows. The estimate long 10yr rate is 3.5%. 10 yr inflation is anybody’s guess. Let’s call it 2.5%.

So, 10 year life time value of this “stimulus” is $-587,520,639.

Now, that doesn’t mean that this isn’t a good project.

The above is not the whole story. It doesn’t include the GDP growth that results from the operation of the complete project (in our example we’ll say this project is completed in the first year).

If this is a road it saves time and fuel. That would need to be accounted for for the life of the road. If the road quickly is filled to capacity we lose the resulting time and fuel savings, but would need to include the addtional economic activity that happens because of increased traffic (not many people drive on a road for the sheer joy of it, they are usually going about some sort of work or consumption).

I’m not sure how to estimate that. But, for the stimulus to make sense it would need to have produce real value each year of its life of $588 million or $12 million real per year for a 50yr life.

My problem with the concept of multipliers for government spending is that I am reasonably sure the dollars (or euros or drachma) don’t know who spent them. Why should there be a 1.2741 multiplier for the effect on the GDP of a dollar spent by US government but some other multiplier for that same dollar spent by the taxpayer that provided it?

In the end, it all boils down to productivity and the only edge private enterprise has over the esteemed intellects in our government is that (rightly or wrongly) the folks in industry at least try to take a set of inputs; process these inputs; and end the day with something that is worth more than the inputs they started with. Governments usually place other priorities higher up their list.

Managing roads, forcing the populace to educate their childrem, and maintaining a legal system are all basic utilities that governments tend to do better than free markets. Managing economies…ehn, not so much.

Circling back to Chinn’s article…if the government component of GDP is too big and there isn’t any plausible way to grow the economy while holding it constant…well, maybe we just have to live with fiscal contraction for a while. Yeah, I know, “Burn the heretic!”…

Oh my. Since this is an economics blog I would have expected commenters here to at least understand multipliers.

aaron At some level I’m sure you know that GDP is a flow variable, but I don’t think you actually have an intuitive grasp of what that means. So let me try to help you out with a simple analogy. Imagine you’re very hungry and stranded in the woods. You see a fast moving stream and periodically a school of minnows swims by. Fortunately you have a net; but the net has a lot of holes in it and half the fish caught in the net will escape back into the stream. It has a fish multiplier of 0.5. Not quite up to Christ’s standards of fishes and loaves multipliers, but that’s just the way it is. A Keynesian fisherman would throw the net into the stream and accept the fact that half the fish will escape. Apparently you would prefer to let all of the fish swim downstream so that they could procreate over the long run. Of course, over the long run you will be dead from starvation.

Part of the problem is that you see the issue as a choice between saving money for private sector investment versus having the government spend money in order to stimulate the economy. This is the view of the macroeconomy as being just a larger version of the household economy. But that’s just wrong. We’re in a liquidity trap recession. That means the money you “save” by not having the government increase fiscal spending is not saved at all; it’s simply lost forever. For example, suppose $1B in fiscal spending increases GDP by $0.4B. You would probably argue that the taxpayer has lost $0.6B, and therefore the taxpayer is worse off. But what happens if the government does not spend $1B. The answer you would give is that the taxpayer has saved $1B; but that is wrong. If not spent by some one or some entity, that flow is forever lost. True, the stock variable of “money” is saved, but that is just a stack of green paper with pictures of dead Presidents. The economic effect is exactly the same as burning that $1B and then printing a new stack of green paper at some time in the future. It’s exactly the same thing as allowing all of those minnows to swim downstream.

Where you go off track is in thinking like a household, where you have the illusion of saving by not spending. It’s an illusion because if everyone tried to save and no one borrowed, then no one could actually save because banks would charge you a penalty to keep money in their vaults; i.e., there would be a negative interest rate. In a liquidity trap that’s what happens, but households don’t see that because they pay attention to the stock variable rather than the flow variable. But in macro the govt has to focus on the flow variable.

Thank Keynes for slugger.

The problem with slugger’s explanation is that it is aimed at aaron, who has been participating on this blog long enough to have been exposed to the arguments slugger offers, and has not been able to absorb them. Heinlein had advice for just this situation – something about teaching a pig to sing.

The argument for larger fiscal multipliers cross fertilizing the European zone, would be more understandable, should readers had not be made privy of the non homogeneous elasticity of supply and demand for goods and services within the Eurozone. The same causes are deemed not to produce the same effects with expanding fiscal multipliers (Tamim Bayoumi and Barry Eichengreen 1994 ) Econbrowser “The Euro Zone Crisis: Political and Economic Perspectives”.

The net may belong to “The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish” Pushkin

The concept of economic stimulation of the economy is not difficult to visualize. Imagine two opposing sine waves depicting economic growth and government spending. As the economy slows down, the government spending goes up thereby stimulating the economy to grow again.

Of course, the opposite is shown as well. When the economy is robust, then government spending drops significantly and the economy runs smoothly within a narrow band of slight overheating and slight recessions.

But what happens to the economy when the stimulants never stop? The junkie needs more and more stuff to get high. Pretty soon the old stimulants stop being enough and new stimulants are required for that high.

Maybe stimulants aren’t such a good thing. Maybe the junkie needs a little cold turkey to get back to health.

2sb, I understand your mis-understanding. It’s hard to resisty the hope for spontaneous generation.

The 1 billion saved by the tax payer is not lost, it is saved. For example, the taxpayer now needs to incease his savings rate and/or will take much more time to recapitalize to an appropriate level to save, invest, and consume more. The tax-payer is only able to save .4 billion, but is obligated to pay 1 billion plus interest, further increasing the need for savings.

We’re likely past the point of overfishing. Treasury yield do suggest otherwise, but that is probably the result of stuctural problems causing uncertainty, not a belief that the government is excedingly good at investment.

Study: Long-term deficits are linked to 24 percent lower growth

“What’s the real harm of a massive government deficit? Carmen Reinhart, Vincent Reinhart, and Kenneth Rogoff find that high public debt is associated with a significantly lower level of GDP in the long run.

“In a new paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, the researchers examined the historical incidence of high government debt levels in advanced economies since 1800, examining 26 different “debt overhang episodes” when public debt levels were above 90 percent for at least five years…

“On average, the researchers found that growth during these periods of high debt were 1.2 percent lower on average, consistent with Reinhart and Rogoff’s findings in 2010. What they also found, however, was these episodes of high debt and lower growth were quite lengthy, averaging 23 years…

“Such findings strengthen the case for tackling the long-term deficit in the United States, where the debt-to-growth ratio shot past 101 percent in February. But the authors also warn that their paper shouldn’t be interpreted as a manifesto “for rapid public debt deleveraging in an environment of extremely weak growth and high unemployment.””

I haven’t read the Reinhart-Rogoff paper, but some economists wonder about the direction of causation there. That is, perhaps falling GDP, caused by falling govt or private investment was responsible for high public debt.

aaron Sorry, but I’m pretty sure that you don’t really get the stocks and flows thing. You’re approach resembles that of a lot of finance professors in biz skools.

The 1 billion saved by the tax payer is not lost, it is saved.

No, it’s lost. What’s important is the flow of benefits, not the pieces of green paper. Imagine an economy with ten people, each earning $10/yr. Suppose 5 people want to save $1 and 5 want to borrow $1 at the equilibrium interest rate. GDP is $100. Now suppose that there’s a financial shock so that everyone wants to save $1 each and no one wants to borrow even at a zero interest rate. So everyone puts $1 in the bank, where the money just sits there. That is a leakage. Since GDP equals consumption + investment + government spending + net exports, and since this example does not have government and net exports, GDP equals consumption + investment. But since no one wants to borrow, investment equals zero. And since people want to save $1 each, consumption equals $9 each. That means GDP has fallen from $100 (i.e., 10 x $10 = $100) to $90 (i.e., 10 x $9 = $90). That supposed “savings” is lost. Those green pieces of paper might as well go right to the incinerator. Your problem is that you’re thinking like a private household, and that’s why you keep thinking that as long as you physically possess green pieces of paper you haven’t lost anything. You need to learn how to think like an economist rather than an accountant. Notice that in this example if the government borrowed that idle $10 and built highways, that would restore GDP to $100.

Regarding the R&R paper, notice how they fudge things by saying that recessions are “associated” with high debt/GDP ratios. One of the reasons countries have high debt/GDP ratios is that GDP shrinks. No one (except my GOP governor) argue that it’s okay to run a deficit when the economy is at full employment. There is a big difference between a structural deficit and a cyclical deficit. Most of the empirical data in the R&R paper reflects historical episodes under species standards or fixed exchange rates. The R&R argument is not terribly convincing when you start talking about countries that control their own currency and live in a “dirty” flexible exchange rate regime. I’m not arguing that the debt/GDP ratio is unimportant. I am arguing that when you’re the US and in a liquidity trap worrying about the debt/GDP ratio ought to be a second order problem. The time to turn our attention to the fiscal deficit is when interest rates turn positive and the Fed is able to manage the recovery.

Bruce Hall But what happens to the economy when the stimulants never stop? The junkie needs more and more stuff to get high. Pretty soon the old stimulants stop being enough and new stimulants are required for that high.

Try a different metaphor. Instead of economic stimulus as cocaine, think of economic stimulus as an electric shock that jolts the economy out of a low output bad equilibrium and shifts it to a higher output equilibrium. One of my complaints about ARRA was that it saw recovery as gradually approaching equilibrium from below the trend line. That’s fine for your garden variety recession; but with a deep balance sheet recession teetering towards deflation what’s needed is a sharp shock that overshoots trend growth rather than approaching trend growth from below. The risk of overshooting trend growth is inflation, but I’d rather deal with inflation than chronic unemployment, deflation and low output. We know how to fix inflation. When it comes to understanding deflation and a liquidity trap…not so much.

Definitely something to consider. The duration though suggests causality, and the prevalence.

aaron: Suggest you read Ugo Panizza and Andrea F Presbitero for some assessment of causality in R&R.

Arron

I suspect you are capable to see through the blather offered by slug. Let’s return to his multiplier fish net analogy. First the multiplier he described is not the government spending multiplier but a private person who happened to own a net that was only 50% efficient. But fortunately the analogy can be corrected to account for the type of government that is so desired by the likes of slug and also, unfortunately, by Prof. Chinn. So here is goes.

It starts the same, a person and a fishing net that currently has holes in it, so is only 50% efficient. The market for his fish has been diminishing lately so in response he has been using his net longer with less maintenance. But at last, he has, by reducing his expenses, and by putting a few fish away for such a time, he is able to spend his days and savings repairing his net. That means he will not be fishing for awhile.

But the government is watching its statistics, and notices that fishing is not being done. What to do? Well by praying to Lord Keynes, the answers appears, the government must fish. But the government has no net, what to do? It does what all governments must do, it takes the net away from the fisherman, and casts the holey net into the river and catches the 50%. Of course the government is not a very good fisherman, so much of its catch spoils, and of course, it had to keep some of the fish to feed the government, but be thankful, a very few fish did enter the fish market. It is called the multiplier.

So here we stand, the government is proud, it has brought fish to market. But also remember, it is a poor fisherman, so the net has continue to wear, and when the government again took the net to the river, but it was only 25% efficient, but that was good enough because after spoilage it could still feed itself even though no fish made it to the market this time. And the net continues to deteriorate.

So the situation now is an experienced fisherman whose livelihood, his net, has been taxed away. The government has a net of little use, because it really doesn’t care about a net, it has so many greater concerns. And I just realized, slug’s starving man is again walking through the forest, it is the former fisherman but this time he has no net.

But do not let this worry you, the government is certain it can continue to find a new net to take from somebody, forever.

And BTW Arron, what Heinlein would say if it was his net that was being taken, and he had a means to escape. Nothing, but a big bang would be heard and he would still have his net.

Who are Panizza and Presbitero? I have never heard of either. Panizza is a UN development guy; Presbitero is junior faculty at an Italian university at a time when Italy’s debt is very much an issue. These guys are not exactly Larry Summers, and they’re proposing academic findings in the midst of a hot, and to Italy crticial, debate on stimulus spending. So neither the source nor the context looks neutral to me.

And even P&P are not entirely convinced:

Most policymakers do seem to think that debt reduces growth. This view is in line with the results of a growing empirical literature which shows that there is a negative correlation between public debt and economic growth, and finds that this correlation becomes particularly strong when public debt approaches 100% of GDP.

“Do high levels of public debt reduce economic growth?” we follow the econometric procedure of trying to reject the proposition that “debt has no growth effects”. Our research shows that this proposition cannot be rejected, so it may well be that it is true. We cannot, however, be sure. Think of a murder trial where the jury finds the man has not been proven guilty “beyond a reasonable doubt”. This certainly suggests that he is innocent, but establishing innocence is not what the trial was about, so technically, we cannot claim that the jury declared him innocent.

Having said that, I would expect there is some truth in their assertions. Increasing public debt from, say, 10% of GDP to 20% of GDP probably won’t cripple an economy. And debt alone is not the issue. If it’s used for productive purposes, it should produce a positive return. Ah, but does public choice theory allow it to do so?

It is an age-old riddle that has perplexed generations: Which came first, the chicken or the egg?

Now British scientists claim to have finally come up with the definitive answer: The chicken.

“The scientific and philosophical mystery was purportedly unraveled by researchers at Sheffield and Warwick universities, according to the Daily Mail newspaper.

The scientists found that a protein found only in a chicken’s ovaries is necessary for the formation of the egg, according to the paper Wednesday. The egg can therefore only exist if it has been created inside a chicken.”

and the paper to conclude

“Now you can construe this “finding” in another way: the chicken temporally precedes its egg. That is, you have to have an adult chicken before it can make eggs. But we already knew that, and finding out that adult chicken proteins help make adult eggs doesn’t add anything”

Economist may conclude as well the debts may precede the growth slow and we still do not know by how much,before becoming a drag on GDP growth.

Now, let us turn to the problems of debt and stimulus spending. There are many beyond the simple debt to GDP question:

Does stimulus spending impede structural re-balancing?

As there is no agreement about what a recession actually is, there is no agreement on this point either. If a recession is about changing relative prices and property rights to accommodate changed economic realities, then stimulus spending will tend to impede, rather than promote, necessary adjustment. We’ve seen a good bit of this in Greece, for example, where government promises made were not kept.

Debt is a critical non-market failure of democratic governments

Everyone wants more services and lower taxes. Increasing debt makes this possible. Democracies, regardless of the business cycle, tend to run deficits in good times and bad. Because voters cannot directly perceive debt, they will allow it to accumulate. (Imagine that a government official came to your door and asked you to personally guarantee $25,000 of government debt. Who would do that? But that is, in fact, what has happened in the last four years.)

Off balance sheet liabilities reward key constituents

At the national level, this is SS and Medicare/Medicaid. These are unfunded implicit liabilities. (Both Republicans and Democrats are guilty of this.)

It’s even worse at the state level. California is exhibit #1. Take Vallejo or San Jose. In essence, the governments there rewarded unions with massive off-balance sheet liabilities that are now killing these communities. New Jersey is hardly better. I suspect we’ll have some significant problems in my hometown of Princeton as well. (Are these problems all in Democratic strongholds?)

Debt can be a means to expand the scope of government

To all appearances, Pres. Obama would like to expand the government. So would Menzie. I can accept that, but I also understand that this implies that debates about debt are more than that. They are debates about the fundamental direction of policy, not purely debates about whether stimulus works on not.

If we want to make these purely debates about stimulus, then we would want to align the incentives of politicians (and economists!) with sustainable prosperity. If economists’ bonuses were tied to GDP growth less growth of debt, then I’d know that either the debate really is i) about maximizing sustainable growth or ii) about an issue so vital to the economist that he’s willing to forego a bonus to achieve a broader social goal. In either event, the economist’s credibility would be greatly enhanced.

As it is, however, the debt debate is so convulted that I cannot distinguish political from policy debating points.

Ed Hanson You obviously completely missed the point of the humble fish catching analogy. The point I was trying to make to aaron was how GDP is more like a stream than a pond. In aaron’s world there’s this big stock pond of economic assets. If you drop in a line to pull out fish and half of the fish fall out of the net and onto a stone and die, then that represents a complete waste. You would have been better off just leaving those fish in the pond for later consumption until you repaired the net. That’s how households and businesses view spending. But that is not the best way to understand GDP. GDP is more like a stream with fish swimming along; and once they’ve gone past you they never come back again. If private sector households and businesses are too busy repairing their nets to catch the fish as they go by, then it is better for the government to use its resources to catch at least some of the fish. The only way you completely lose benefits is by not fishing at all. The Keynesian view is that half a loaf (or half a net) is better than nothing.

Multipliers are really something different. Multipliers are all about the effects of shocks to aggregate demand. The fiscal spending multiplier is the change in GDP (dY)with respect to a change in government spending (dG); i.e., dY/dG. You are so confused and muddled that you don’t even understand which curve I’m talking about. Fiscal multipliers are about pushing out the aggregate demand curve. Your blatherings about controlling the economy and regulating fishing is entirely on the aggregate supply curve side of things. Keynesian economics has almost nothing to say about the aggregate supply side. The point of Keynesian economics is that sometimes effective demand falls short of what the supply side could be producing. Whenever that’s the problem the task of economists is not to figure out how to further push out the aggregate supply curve, but to figure out how to close the gap between potential output and actual output. If you want to intelligently critique a Keynesian position, that’s fine; but before you attempt that you should at least bother to understand what Keynesians mean by fiscal multipliers. And if you want to contribute to an economics blog it might be useful if you at least learned the difference between demand and supply curves.

Steven Kopits Having said that, I would expect there is some truth in their assertions. Increasing public debt from, say, 10% of GDP to 20% of GDP probably won’t cripple an economy. And debt alone is not the issue. If it’s used for productive purposes, it should produce a positive return.

You’re confusing two different kinds of public debt. When the economy is operating normally and at something like full employment, then it’s perfectly sensible to talk about government borrowing only if it has a positive return. People can argue about the proper discount rate to use, and people can argue about the best way to aggregate the benefits of public goods; but in principle I don’t think anyone would disagree that in normal times the government should not crowd out private sector investment unless the government’s intended project produces a benefit stream at least equal to the marginal alternative investment in the private sector. No disagreement there. But the issue of government borrowing during a ZIRP liquidity trap type of economic stagnation is a very different problem. When you’re in a ZIRP environment and the real 10yr Treasury is virtually zero or even negative, then the market is telling you that there is no crowding out and what’s needed is some crowding in. If households and businesses only want to save income rather than borrow to invest, then it is up to government to absorb that surplus saving and provide households and businesses with the financial assets needed to facilitate that demand for saving. In other words, government needs to become the borrower of last resort. If that doesn’t happen then aggregate demand will continue to shrink. That’s because when you’re at the zero interest rate the only way to equilibrate savings and investment is by shrinking income. Sorry, but that’s just the way the math works.

In essence, the governments there rewarded unions with massive off-balance sheet liabilities that are now killing these communities.

Actually, governments appeased taxpayers back in the distant past by offering generous deferred compensation packages rather than high current year wages. Now the bill is coming due and taxpayers want to renege on the agreements they made in the past. This is typical of myopic voters. But what you’re discussing here is a not really about fiscal stimulus and the contractionary effects of cutting government spending. What you’re talking about has more to do with the proper role of government spending and what kinds of services government ought to provide in lieu of the private sector. That’s an important discussion, but it doesn’t have anything to do with fiscal stimulus. Remember, it’s always a good idea to ask yourself which curve your argument refers to. If you’re making an argument about long run growth and productivity, then you’re talking about the aggregate supply curve or neo-classical growth model. Fiscal stimulus doesn’t have anything to say about that beyond the hysterisis argument of what happens to productive capital when it sits idle too long.

2sb, you have come up with an analogy that gets you the right words to get points a specific exam. You are oblivious to the how’s and why’s.

Steven Kopits: You write “Who are Panizza and Presbitero?” — as if being a UN economist disqualifies one as an expert. Seems kinda snobby. In any case, let me suggest you acquaint yourself with GoogleScholar, going forward.

I am plenty snobby.

Having said that, Panizza has a substantial pedigree, is quite prolific, and is a pretty much down the middle, often-cited guy. I stand corrected in my insinuation–although I don’t class the UN in the same camp as the IMF, ECB, the Fed or Harvard. They are in the same class?

Has Econbrowser referenced Panizza before? I don’t recall having seen his name here before. You should feel free to profile economists and areas of research.

The governments appeased taxpayers with generous packages?

Do you know what the pay packages of your local government employees are? I sure don’t. And governments they appease taxpayers with these sorts of packages in right to work states? Not that I can tell–but maybe you have some good counter examples. These pay packages had everything to do with hiding true costs, not with making informed trade-offs for voters.

Steve Kopits: Not cited in Econbrowser, but I have cited in a published paper. He is also a key contributor to the literature on why developing countries are often unable to borrow internationally in their own currency.

Panizza and Presbitero

One may read the paper and methodology at this address: (http://polis.unipmn.it/pubbl/RePEc/uca/ucapdv/panizza198.pdf

The conclusion is modest enough to receive an agreement.

“What did we find? Does debt have a causal effect on economic growth? Unfortunately, our answer to this question is: “We don’t know”

One may show equal respect for the assumption:

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so”

attributed to Mark Twain

Unfortunately the assumptions have to be expanded to debts repayments should it be a matter of importance, unfortunately the debts dimension have to be expanded to the interest rates components of the debts and unfortunately the percentage of governments expenditures to GDP should give a larger dimension to the debts repayments (in) ability versus GDP growth. As S Kopitz reminded, debts are a measure of productivity, the micro business world is still recalling that component and bankruptcy procedures are still put in force. Debts have to be underwritten, debts have to be placed among investors and it involves money creation, money supply, a true recognition of the inflation that is not to be restricted to wages and everything else is non inflationary.

The same paper acknowledges potential negative chock and leave a larger room to multiple variable range of possibilities that are not explored in the paper as “nothing is lost, nothing is created, everything is transformed”

“The fact that we do not find a negative effect of debt on growth does not mean that countries

can sustain any level of debt. There is clearly a level of debt which is unsustainable (for instance,

when the interest bill becomes greater than GDP) and a debt-to-GDP ratio at which debt

overhang, with all its distortionary effects, kicks in”

No casuistic, just plain facts, we still have to explore and understand or to discover through trials,the negative consequences of public debts.

Slug

you think I do not understand your analogy, but believe it is you who does not understand it. I will point out some your own words from your response

“If private sector households and businesses are too busy repairing their nets to catch the fish as they go by, then it is better for the government to use its resources to catch at least some of the fish.”

I will point out two things. One, your original analogy had no government in it, which my rewrite corrected, properly as it turns out as related to the above quote. Which leads to two, what you seem not to understand, the government has no resources. It does have processes, such as taxation and regulation which by definition confiscate from the private sector, either wealth or opportunity. In the case of the the fish analogy, and in the real world, the government must take from those who earn first, in order to do anything for whoever it chooses to do for. As the rewritten analogy demonstrated, for the government to fish it first must take the resource from some person or persons. And I stand by the other main point, government actions simply does not reach the the efficiencies of the private market. Remember the truism of Milton Friedman about someone own money spent on himself and those very close, spending other’s money on oneself or those very close, or finally spending other’s money on someone not close or even unknown. Guess which is the least efficient and which is the Keynesian type government.

Now away from the fish, and to more of quotes of yours.

“Keynesian economics has almost nothing to say about the aggregate supply side.”

Quite true, which goes along way to demonstrate the poor understanding Keynesians have of the real world and what is important.

“The point of Keynesian economics is that sometimes effective demand falls short of what the supply side could be producing.”

Keynesians have pathetic understanding of why supply sometimes fall short of what an extrapolation from previous time would seem to indicate. Production is difficult and the work is hard and risky. There comes times, when government process simply makes the decision to produce more at the margin simply not worth it compared to leisure. High marginal tax rate, increased complicated regulation, certainty of higher tax rates in the future, and a government that continue to spends beyond the tax capacity of the nation, which historically is less the 20% GDP all reduce prodution at the margin. Simply put INCENTIVES MATTER. And it is production that matters not mathematical construct of aggregate demand.

Steven Kopits Do you know what the pay packages of your local government employees are? I sure don’t

Yes, I do. One of my brothers was on the city council and the pressures local politicians face from voters is the same as national politicians. Voters and taxpayers want something for nothing. One way politicians try to square the circle is by offering public sector workers generous deferred compensation packages in exchange for lower salaries. That kicks the problem down the road.

My town had a history of police corruption and misconduct because salaries were so low that they had to scrape the bottom of the barrel. One cop impregnated several local high school girls. Another cop (who lived down the street me) went over the edge and held his family hostage in a shooting situation. One police chief was fired for shooting a family’s dog. You get the picture. The city council bit the bullet and upgraded the quality of officers but had to increase the compensation package. When the recession hit some on the city council wanted to renege on the compensation packages. The police department told the city council that the police would then have to generate more revenue by issuing more traffic tickets and asked the city council for permission to expand their zone to include a nearby interstate. Voters didn’t like having to pay higher taxes in the form of ginned up traffic tickets, so the city council and the mayor got into it with the police department. Then there was a fight between the police and the fire department. Eventually the police chief and most of the officers resigned and found other jobs. A nearby community had similar problems. Their solution was to eliminate the local police department and leave it to the county sheriff’s department to handle emergencies. That put resource pressure on the county. And so it goes.

Clearly none of these problems were caused by public employees. The root problem is irresponsible and myopic voters who cannot see past lunch and want something for nothing. Voters want low taxes, expansive government services and no deficit. And they’d like a pony too.

BTW, we still don’t have a fully staffed police force, but voters did approve an enormous indoor football practice facility for the local high school. When you enter the town there’s a sign that proudly displays all of the state football championships.

Ed Hanson your original analogy had no government in it

Actually, the original analogy did have government. That was the Keynesian fisherman.

the government has no resources.

And without government no one else has resources either. One of the central functions of government is the establishment and enforcement of property rights. But more to the point, government adds value. Courts add value. The military adds value. Regulations add value. As an old econ prof of mine used to point out, many of today’s conservatives are actually closet Marxists in the sense that they share a common belief in the labor theory of value and deny that government adds value. Shall we start calling you Comrade Ed Hanson?

which goes along way to demonstrate the poor understanding Keynesians have of the real world and what is important.

The truth is that no one really has a good understanding of how to increase productivity. The neo-classical Solow growth model is kind of a kludge that sort-of-kinda does the job, but not at a profound level. And almost all of the “supply side” BS that you hear from chamber of commerce types and The Club for Growth is just inconsistent nonsense.

it is production that matters not mathematical construct of aggregate demand.

Sounds like you (along with Ricardo) are still living in 1979. If you think today’s problem is one of production capacity straining under the yoke of oppressive government regulations, then you’re hopeless. An economy that cannot produce as much as people demand is characterized by inflation and high interest rates and not by hovering deflation and a ZIRP. You’re a one trick pony. Every economic problem is due to high taxes and government regulation. And in your world economic equilibrium is (somehow) determined through one and only curve. Sorry, but you’re just not a serious person.

National debt becomes a problem when the interest payments are large enough to have serious negative effects. There has to exist such a level, call it L.

If interest payments are L, the Debt (D) must be L/I where I is the current market rate for government debt. This market rate is set in part by transactions from citizens and partly by those of foreigners.

With citizens the problems involve willingness to pay the interest. When this is a problem, a society may, quite reasonably, renege, like a borrower who’s mortgage is 50% under water and is out of work.

Of course, lenders aren’t all idiots. They realize there is default risk and want to be compensated by higher rates, which aggravates the problem. There’s a feedback effect that can run out of control at some rate. Of course nobody knows exactly what that magic rate is, because the problem is reflexive. Lenders want to get out before it’s reached.

Imagine a headmaster who promises there will be an unexpected day off at some point in the semester. Being a lazy student, I won’t do my homework if I know what day it’s going to be. I know it can’t be the last day, because then it wouldn’t be a surprise, but this means it can’t be the next to the last day, because it could never reach the last day, but this proves by recursion there can’t be any possible date. Then one morning, the headmaster says, “Surprise.” People have devoted considerable thought to this paradox. AFAIK there’s no solution.

If you’re an investor faced with this, you want to stay well away from the last day.

Of course the economic distortions from high interest payments can be a problem, but the real problem is mobility of capital, human and financial. The capital who you most want to stay is that which will find it easiest to leave.

Greece has all of the above problems –

No market for its debt at a price it can pay (of course it’s not clear what that price is)

Mobile capital. Huge amounts of both money and talent have left. They don’t have to stay.

The problems have reached a level which destroys the social cohesion needed to solve them.

High risk of default. Maybe we don’t know what the limit is, but 165% of a falling GDP isn’t promising.

This gets us to Panizza and Presbitero. There’s no real contradiction with R, R and R. They’re mostly arguing about whether the glass is half full or half empty.

“While such an interpretation justifies long-term policies aimed at reducing debt levels, it also implies that countries should not implement restrictive policies in the middle of a recession. These policies are the reason for the negative effect of debt on growth. Yet, policymakers under pressure from market participants might not have an alternative. This is why we need prudent fiscal policies and lenders of last resort that can rule out multiple equilibria (De Grauwe 2011).”

The problem is the last bit:

“lenders of last resort that can rule out multiple equilibria.”

If everybody is depending on someone else filling this role, things get ugly.

Also sovereign debt serves as safe collateral. When the debt is no longer treated as safe (that is suitable for low information trading, where there is no need for individual examination of the documentation), it is no longer part of the collateral supply, which is the broadest of broad money. This “tight money” raises the demand for the remaining collateral (like treasuries at 0 or negative rates), and spills over into other forms of money.

Of course debtors who control major international currencies have more room to maneuver, and the US has the most room of all, but it isn’t unlimited.

It’s really necessary to look at total debt public and private. It can give a very different picture. Look at Spain and the UK.

It’s also necessary to look at flows, but the debate about the effect of new net debt on spending and GDP (which are NOT synonymous) has become rather contentious. Maybe later.

Slug

You can continue to try to pigeon hole anyone who disagrees with you all you want, but it is just a tactic.

It seems your economic theory is strictly Keynesian and there for anyone who disagrees must adhere to another failed model, in this case your labor value theory. Sorry, doesn’t fly. And you are wrong about your characterization that government adds value, it does not. A reasonable, limited government can facilitate increased value of the created by individuals and voluntary association of people, but that is not the same ass adding value. As noted I am not an anarchist, but government is quite capable of its necessary functions at less than 10% GDP, the additional more than 30% it is taking is nothing but a drag on economic growth and liberty.

You state that no one has a good understanding how to increase productivity, what you do not realize is what is true is no one knows how to command increase productivity which is what governments evolve to attempt. Rather than appeal to the Chamber of Commerce, or the Club for Growth, I am quite satisfied with Friedman and Hayek.

And so you wrote, “An economy that cannot produce as much as people demand is characterized by inflation and high interest rates” to demonstrate how completely wrong you are.

2slugs wrote: stuff.

Just wanted to say that I’m reading and appreciating your posts. Your writing has shaped the way I think about Macro and I appreciate your willingness to persevere despite your critics remarkable ability to persistently miss the point.

Ed Hanson I am quite satisfied with Friedman and Hayek

First, I seriously doubt that you have ever actually read any of Hayek’s purely economic works. Most Hayek fanatics have only read the political polemics. But if you haven’t read Hayek’s economic works I won’t come down too hard on you because it’s pretty much a waste of time. Shot through with inconsistencies and thoroughly discredited since Kaldor patiently dismantled his arguments in a very public debate. That’s why no one takes his economics seriously today and the people who do read Hayek focus on his political writings. So are you telling us that you really believe all that mumbo-jumbo about concertina effects and lengthening production cycles? Good God!

As to Friedman, you do know that Friedman worked within the Keynesian tradition, right? Just because Friedman had a strong faith in free markets does not mean he didn’t accept the basic Keynesian framework and the emphasis on a fall in aggregate demand as the cause of recessions. Are you familiar with Friedman’s Permanent Income Hypothesis? That’s pretty much standard stuff in intro macro textbooks. In the crude terms of 1960s macro, the debate between old school Keynesians and Milton Friedman was a debate over the slopes of the IS and LM curves; but both worked within the general Keynes/Hicks framework.

And so you wrote, “An economy that cannot produce as much as people demand is characterized by inflation and high interest rates” to demonstrate how completely wrong you are.

Oh my. So in your world holding supply fixed and increasing demand does not increase the price. Right.

Rodrigo Thanks. When my office had some contest for a catchy mission statement slogan I suggested words I like to live by: “Missionary Work Among Savages.” It wasn’t selected, but I like to think it has some relevance here.

I was in Ghana doing development stuff and I just saw this now. I would like to thank Menzie for linking our paper and for his kind words about my past work.

I also have a comment about Steven Kopits original post about our paper (Who are Panizza and Presbitero?). Andrea and I welcome any criticism that points to flaws in our methodology, data, or whatever; but I think that it is not very constructive to judge the quality of a paper based on the seniority/nationality/place of employment of its authors.