Action is needed in the eurozone and Japan, according to the Treasury Secretary.

From Secretary Lew’s recent speech:

“In short, status quo policies in Europe have not achieved our common G-20 objective of strong, sustainable, and balanced growth. The ECB has taken forceful steps to support the economy through accommodative monetary policy. But as recent economic performance suggests, this alone has not proven sufficient to restore healthy growth. Resolute action by national authorities and other European bodies is needed to reduce the risk that the region could fall into a deeper slump. The world cannot afford a European lost decade.

…

“In Japan, the “three arrows” of Prime Minister Abe’s economic program were designed to forcefully combat deflation and fuel sustained economic growth. The first two arrows – monetary and fiscal stimulus – contributed to stronger growth in 2013, but growth has weakened this year as Japan stepped back from its efforts on the fiscal side. The third arrow – structural reforms – has not been fully released. Earlier this year, the Abe Administration put forward corporate governance reform and other structural measures. Even so, the test will be whether the third arrow is sufficient to transform Japan’s economy, and the jury is still out.

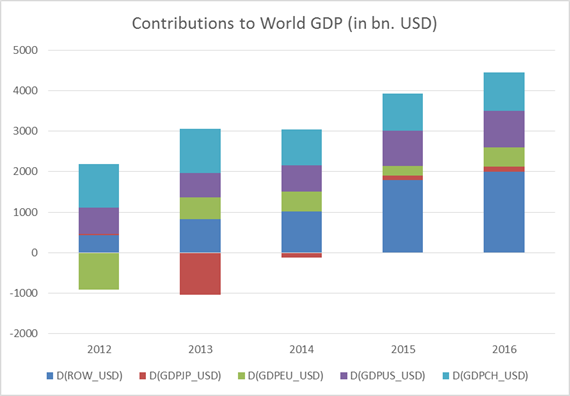

The importance of Japan and the euro area growth is highlighted by the amount of world GDP accounted by those economies. Figure 1 depicts the contributions in billions of US current dollars, as projected in the October World Economic Outlook.

Figure 1: Contributions to world GDP growth in billions of US dollars, from China (light blue), US (purple), euro area (green), Japan (red), and rest-of-world (dark blue). Source: IMF WEO database (October 2014) and author’s calculations.

The euro area’s travails are well known, and while it eked out a 0.2% q/q growth in the 3rd quarter, as pointed out, the fact that a sigh of relief was heard is testimony to the fact that more needs to be done, with respect to credit easing by the ECB and the governments in terms of loosening fiscal policy.

In contrast, developments in Japan are somewhat less familiar. While Japan is not adding much to the 2014 increment to world GDP, it’s a big change from 2013 when it was a large debit entry. In order for Japan to remain a positive entry for 2016, growth has to be maintained. And here, it’s clear there are big challenges.

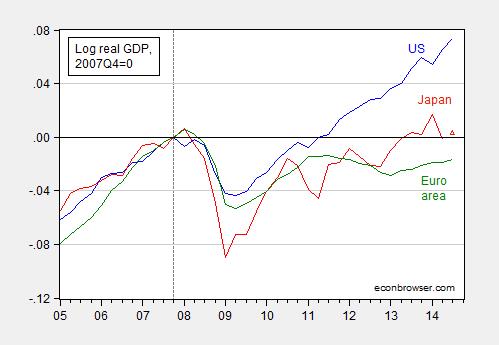

Figure 2: Log real GDP in US (blue), in Japan (red) and euro area (green), all normalized to 2007Q4=0. 2014Q3 observation for Japan is based on 2.25% q/q SAAR growth rate median forecast from WSJ survey. Source: BEA, OECD via FRED, and ECB, WSJ and author’s calculations.

An aside: Note that the US, which has pursued more expansionary fiscal and monetary policies than the eurozone and Japan (and the UK) has expanded much more rapidly.

The downturn in Japanese GDP has been attributed in large part to the implementation of the consumption tax rate hike, the first step of which was an increase from 5% to 8% in April. The second stage of the consumption tax hike, 8% to 10%, is likely to be delayed [Landers/WSJ]. Krugman notes the rationale for the delay (raising taxes, and/or otherwise withdrawing fiscal stimulus in the midst of a fragile recovery is counterproductive); the position of Koichi Hamada, a key Abe adviser, is noted in this FT article (Nov. 4):

Koichi Hamada, a former economics professor at Yale University who was among the architects of Mr. Abe’s growth-enhancing policy known as Abenomics. Mr. Hamada stressed that the tax increase should be delayed until 2017 in the absence of a strong pickup in economic growth.

Mr. Abe will hold four more panel sessions over the next two weeks to hear from a total of 45 experts who are believed to hold varying views on tax policy.

Many experts believe the government should go ahead with the tax increase despite the risk of slowing economic recovery. Among the panelists espousing such a view Tuesday was Nobuaki Koga, president of the Japanese Trade Union Confederation. “The sales tax increase to 10% should be implemented as agreed upon,” Mr. Koga told the panel. “The burden of maintaining the social security system should be shared by taxpayers.”

Aside from the clear policy implications — tax increases to consolidate public finances should be implemented during times of positive output gaps (e.g., United States 2004-06) rather than times of economic fragility — there are implications for our thinking about what type of macro model applies to the real world. From Simon Wren-Lewis musing in Mainly Macro about how to think about the consumption tax increase, over a year ago:

Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has decided to go ahead with an increase in consumption taxes from 5% to 8% in April 2014, with a further increase to 10% planned for later. Will this be the first step to reducing the very high level of government debt in Japan (in net or gross terms, the highest in the developed world), or will it derail the recovery? In many ways the answer depends on whether you like your macro state of the art, or more antique.

Consider the antique first. Raising the consumption tax takes real purchasing power out of Japanese consumers’ pockets. It is a straightforward fiscal contraction, on a very large scale: the last thing you need when we only have the first signs of a recovery. Now in theory this fiscal contraction could be offset by monetary expansion, but can monetary expansion really be strong enough to offset a fiscal contraction of that size? Some macro antiques were always rather suspicious about the potency of monetary relative to fiscal policy anyway, but in a liquidity trap those suspicions become certainties. Even if the central bank does succeed in reducing real interest rates by raising inflation, is that going to be more powerful than the cut in real incomes that this higher inflation brings?

So why might modern macro be less pessimistic about the impact of the consumption tax increase? For one thing it might be more optimistic about the potency of monetary policy, particularly in an open economy. If the central bank is really committed to bringing about a recovery come what may then it may be prepared to see inflation go well above 2%. But I would suggest the more important difference lies with the fiscal impact of the tax increase. Modern macro could bring two arguments to the table.

The first is Ricardian Equivalence. The consumption tax increase has been planned for some time, so consumers will have already factored in its impact into their consumption decisions. Even if they had wondered if the tax increase might be postponed, some taxes will have to rise at some point. So if all the Prime Minister has done is confirm that tax increases are going to come sooner rather than later, the logic behind Ricardian Equivalence will mean that the impact on consumer spending will be second order.

The second involves the incentive effect of higher sales taxes, which I discussed recently. If monetary policy does not try and offset the impact that higher sales taxes will have on inflation, then anticipation of the tax could lead consumers to bring forward some consumption. What this really involves is fiscal policy mimicking monetary policy. Or to put it another way, if you were doubtful that monetary policy through Quantitative Easing could raise inflation, here is a surer way to achieve the same thing.

The common theme here is the importance that modern macro places on expectations of a fairly rational kind. Yet even if you are happy to go along with this, there is an important proviso that does not get emphasised enough. How did consumers know that the budget deficit would be reduced by raising taxes rather than cutting spending? If they had expected the deficit to be reduced by lower government spending, they will not have expected a fall in their post-tax real income. For these consumers the Prime Minister’s announcement will come as a surprise, and they will reduce their consumption as a result.

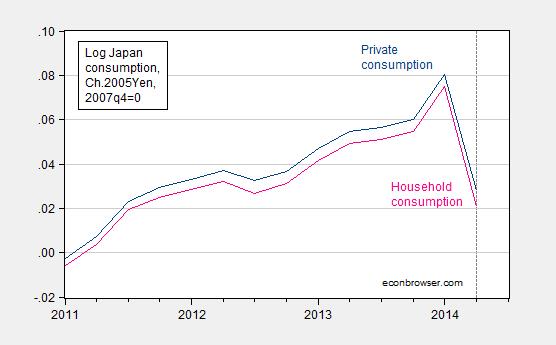

Well, look at the behavior of consumption in Japan.

Figure 3: Log real private consumption (dark blue), and household consumption (pink), both in Ch.2005Yen, normalized to 2007Q4=0. Dashed line at 2014Q2, implementation of the tax increase. Source: Cabinet Office/ESRI, and author’s calculations.

Notice that consumption growth was positive until the imposition of the tax. This timing suggests to me that Ricardian equivalence doesn’t hold fully in Japan (after all, as Wren-Lewis notes, Abe’s announcement of a tax increase rather than spending cut should have, if perfectly credible, implied an immediate drop in consumption at time of announcement).

So put me more in “antique” than “state of the art” camp (although the spike in consumption is consistent with moving forward consumption in anticipation of a higher tax rate in the future — so I do believe expectations matter!).

For more on expectations, without infinitely lived consumers, in this post.

“Notice that consumption growth was positive until the imposition of the tax. This timing suggests to me that Ricardian equivalence doesn’t hold fully in Japan (after all, as Wren-Lewis notes, Abe’s announcement of a tax increase rather than spending cut should have, if perfectly credible, implied an immediate drop in consumption at time of announcement).”

“(although the spike in consumption is consistent with moving forward consumption in anticipation of a higher tax rate in the future…”

I always get a bit dizzy trying to keep macro threads consistent. Consider:

We are trying to generate inflation to reduce real debt burdens and get the economy moving, yet Wren Lewis says “Even if the central bank does succeed in reducing real interest rates by raising inflation, is that going to be more powerful than the cut in real incomes that this higher inflation brings?”

I believe Britain experienced the same kind of thing when they upped VAT to show a balanced “austerity” approach that both cut and raised funds for fiscal “prudence”. And I like to note, they cut public investment tremendously even as social spending rose – stabilizer effects due to economic pain – so they a) cut investment spending as b) they reduced consumption with a higher VAT and c) ended up spending as much anyway because of higher unemployment, welfare, etc. spending. An object lesson in the importance of investment spending and in how not to do it right.

My take on the Euro zone: Oil is helping, Russia is hurting

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2014/11/14/q3-euro-gdp-stagnation-russia-or-oil

My take on the message for US labor markets: The underlying trends signal a hot market

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2014/11/14/oil-and-labor

There’s uncertainty whether the economy will be strong or weak in the future.

If the economy turns out to be strong, for example, then more workers will pay taxes and tax rates can be lower.

President of Lincoln University (a black man) attacked for saying women should be responsible for their actions.

Since Menzie is a staunch feminist, he surely approves of this. But then again, this is a university President who is black.

What is a leftist to do?

i fail to see any use for such ignorant drivel on this blog.

Japan slips into surprise recession, paves way for tax delay, snap poll

Mon, Nov 17, 2014

TOKYO (Reuters) – “Japan’s economy unexpectedly slipped into recession in the third quarter, setting the stage for Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to delay an unpopular sales tax hike.

Gross domestic product (GDP) fell at an annualized 1.6 percent pace in July-September, after it plunged 7.3 percent in the second quarter following a rise in the national sales tax, which clobbered consumer spending.

The world’s third-largest economy had been forecast to rebound by 2.1 percent in the third quarter, but consumption, and exports remained weak, saddling companies with huge inventories to work off.”

Interesting juxtaposition of headlines on Drudge:

China to begin tax cutting spree to spur business growth

Abenomics Officially Leads Japan Into A Triple-Dip Recession – Weather Blamed; Nikkei Drops 600 Points, Back Below 17,000

Who will you bet your money on?