Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Anton Korinek (Johns Hopkins Univ.) and Alp Simsek (MIT).

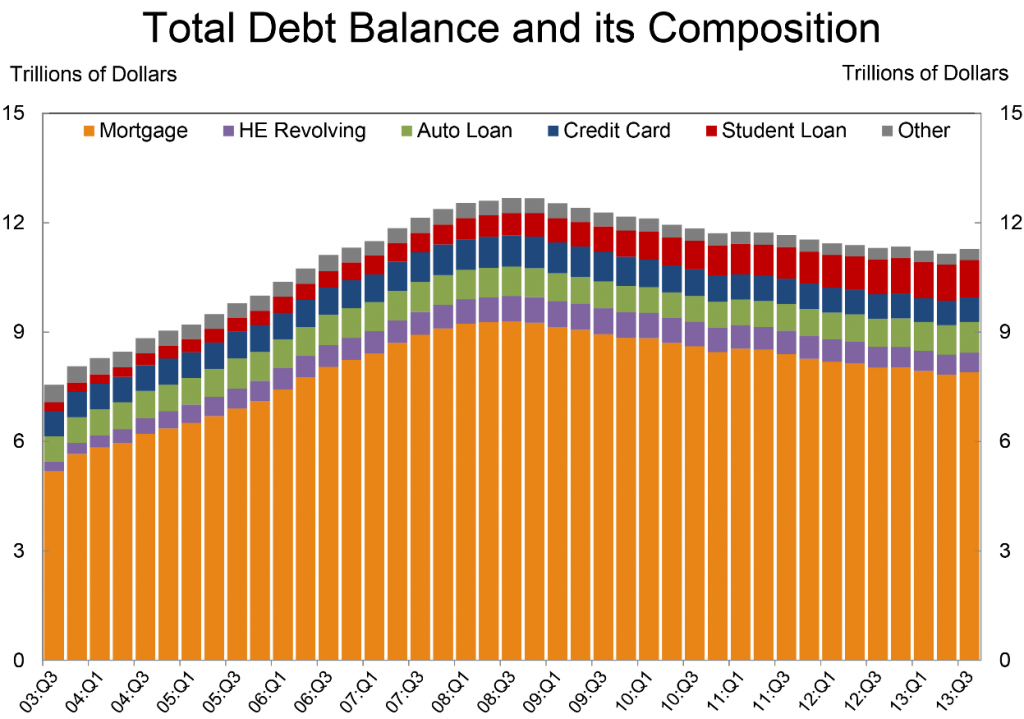

Deleveraging – the forced and rapid paying down of debt – has been one of the key factors behind the Great Recession of 2008/09 and the ensuing slow recovery of the US economy (see e.g. Mian and Sufi, 2014; Mian, Sufi and Verner, 2015). Figure 1 illustrates the dramatic rise of leverage in the household sector before 2008 as well as the subsequent deleveraging.

Figure 1: Evolution of household debt in the US around its peak in 2008Q3 (New York Fed).

Deleveraging hurts the economy because it forces borrowers to repay their lenders, but lenders are far thriftier than borrowers. (This is the reason why borrowers are borrowers and lenders are lenders in the first place.) When funds are moved from big spenders to thrifty lenders, it reduces aggregate demand. During normal times, the Federal Reserve can counteract this and restore aggregate demand by cutting interest rates, but monetary stimulus becomes very difficult once interest rates hit zero – a phenomenon frequently referred to as a “liquidity trap.” This is precisely what happened in the US economy starting in December 2008, and as a result, the economy plunged into deep recession (see e.g., Eggertsson and Krugman, 2012, or Guerrieri and Lorenzoni, 2011). Although policymakers have employed a whole battery of monetary and fiscal stimulus tools since, the effectiveness of such stimulus has been limited, and it has taken the US economy a long time to recover.

In our forthcoming paper, “Liquidity Trap and Excessive Leverage” (Korinek and Simsek, 2016), we argue that the right time to counteract a deleveraging-driven crisis is not after the event but at the time when leverage builds up. If we reduce the amount of debt that borrowers take on during the build-up phase, then the next deleveraging episode will be less severe, and the resulting recession will be mitigated.

At the center of our argument is what we call an aggregate demand externality: Individual borrowers, if left to themselves, do not take into account how their behavior affects the economy as a whole. The argument is similar to the case of environmental pollution, when individual polluters find it rational to pollute because they believe that each one of them has just a minuscule effect on overall environmental quality. When individuals take on debt, they recognize the risk that they may have to deleverage in the future, but they do not recognize that this affects aggregate demand since each person’s contribution to aggregate demand is minuscule relative to the total size. However, when a substantial fraction of the economy is forced to deleverage at the same time, the impact on aggregate demand is severe. Furthermore, if the economy is in a liquidity trap, this aggregate demand externality cannot be offset by the central bank and imposes substantial welfare costs on the entire economy. Similar arguments have also been advanced by Farhi and Werning (2012, 2013) and Schmitt-Grohé and Uribe (2016) in the recent literature.

As in the case of environmental pollution, it is desirable to impose regulations in order to reduce borrowing, either in the form of quantity regulations or “Pigouvian taxes,” so that individuals internalize aggregate demand externalities and take into account the negative effects of their behavior. The overarching objective of such macroprudential regulation is to restrict all financial activities that will lead to lower demand during future deleveraging crises. For example, it is desirable to restrict the leverage of borrowers who may be forced into deleveraging during such episodes. Furthermore, it is desirable to encourage insurance against economy-wide deleveraging episodes, such as mandatory insurance in mortgage markets against aggregate price declines that leave homeowners under water.

Our paper also shows how to quantify the externalities from excessive leverage. The primary determinant of aggregate demand is how spendthrift borrowers are compared to lenders or, in more technical jargon, how much they differ in their marginal propensity to spend. According to Jappelli and Pistaferri (2014), borrowers who are among the poorest 10% of households are more than 25% more likely to spend an additional dollar received than rich lenders. After accounting for the multiplier effects of additional spending, reallocating one dollar of income from such borrowers to lenders reduces aggregate demand by about 45 cents. If we assume, conservatively, that an economy experiences a deleveraging-driven crisis and liquidity trap once every thirty years, then borrowing by the most leveraged households creates on average a negative aggregate demand externality of 45%/30 = 1.5% per dollar borrowed per year. This externality could be internalized with a 1.5% Pigouvian tax on leveraged borrowing or the imposition of equivalent debt limits.

Monetary policy is a bad substitute for such macroprudential policy. In recent debates, it has frequently been suggested that monetary policymakers should raise interest rates to reduce the build-up in leverage. In our paper, we consider this argument carefully, but we find that interest rate policy is at best an imperfect substitute for macroprudential policy and may even, perversely, lead to an increase in leverage. The reason for our result is simple: the conventional wisdom hinges on the observation that higher interest rates discourage borrowing when keeping everything else equal. However, everything else is not equal: higher interest rates generate a recession, which temporarily reduces the income of borrowers and encourages extra borrowing to smooth over the shock. If credit availability is ample, as it was during the early 2000s, then the predominant effect of higher interest rates may be to increase leverage. This may explain why the interest rate hikes by the Fed starting in June 2004 were so ineffective in reducing leverage at the time. Moreover, even when the conventional wisdom holds and higher interest rates do indeed reduce leverage, interest rate policy is inferior compared to macroprudential policy because it is too blunt. That is, it affects borrowers and lenders equally and needlessly creates a recession. By contrast, macroprudential regulation discourages borrowing and keeps funds in the hands of lenders without the need to slow down economic activity.

The proposed macroprudential regulation is fundamentally different from traditional financial regulations which are best described as “microprudential:” in past decades, the main goal of financial regulation was to restrict risk-taking and protect individual financial institutions from failure in order to limit the losses of depositors and the risks to deposit insurance funds. By contrast, the new macroprudential approach that we advocate elevates financial regulation from being about the health of individual banks to being a pillar of macroeconomic stabilization policy, akin to monetary and fiscal policy. Limiting leverage can not only protect individual financial institutions but also prevent future deleveraging-driven recessions and stabilize the macroeconomy as a whole.

This article is cross-posted from the INET blog

References:

Eggertsson, Gauti and Paul Krugman. 2012. “Debt, Deleveraging, and the Liquidity Trap.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 127(3): 1469-1513.

Farhi, Emmanuel and Iván Werning. 2012. “Fiscal Unions.” NBER Working Paper 18280.

Farhi, Emmanuel and Iván Werning. 2013. “A Theory of Macroprudential Policies in the Presence of Nominal Rigidities.” NBER Working Paper 19313.

Guerrieri, Veronica and Guido Lorenzoni. 2011. “Credit Crises, Precautionary Savings, and the Liquidity Trap.” NBER Working Paper 17583.

Jappelli, Tullio and Luigi Pistaferri. 2014. “Fiscal Policy and MPC Heterogeneity.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 6(4): 107-136.

Korinek, Anton and Alp Simsek. 2016. “Liquidity Trap and Excessive Leverage,” forthcoming, American Economic Review 106(3).

Mian, Atif and Amir Sufi. 2014. “What Explains the 2007-2009 Drop in Employment?” Econometrica 82(6): 2197-2223.

Mian, Atif, Amir Sufi and Emil Verner. 2015. “Household Debt and Business Cycles Worldwide.” NBER Working Paper 21581.

Schmitt-Grohé, Stephanie and Martín Uribe. 2016. “Downward nominal wage rigidity, currency pegs, and involuntary unemployment.” forthcoming, Journal of Political Economy.

This post written by Anton Korinek and Alp Simsek.

There was too much money flowing into the housing market before the crisis, and it’s likely too much money is flowing into student loans after the crisis.

A large tax cut with higher lending standards in the housing market before the crisis would’ve caused households to save more, because of diminished marginal utility (the opposite of pent-up demand), to strengthen household balance sheets and the banking sector.

There was a homebuilding boom and a refinancing boom, because too many houses were purchased. So, more household debt was created and the expectation was either home prices would continue to rise or flatten-out.

Gradually raising lending standards, e.g. in 2004, would’ve slowed homebuilding and refinancing. So, there would’ve been less household debt. Some percentage of tax cuts would’ve further reduced household debt, while consumption continued to grow.

I may be mis-remembering, but wasn’t the trigger for the “great recession” excessively loose lending standards forced upon lenders by the government? The lenders then “bundled” these government-forced shaky loans and eventually the house of cards came tumbling down.

http://www.investors.com/politics/editorials/subprime-mortgages-on-march-again-as-obama-pressures-easier-lending/

http://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/u-s-settles-lawsuit-accusing-honda-car-loan-discrimination-n391981

Same song, second verse; a little louder, a little worse?

bruce, you are misremembering. they were not “government-forced” loans. the loans that sank bear stearns and lehman, leading to the financial crisis, were private sector led loans. private sector was trying to profit off of the subprime model. they made more off the interest, and they encouraged refinancing which led to higher profits. subprime was a 2 profit for 1 sale item. it is completely inaccurate to try and blame the government for these activities.

baffling,

“The affordable housing goals imposed on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in 1992 were the major contributors to both the deterioration in underwriting standards between 1992 and 2008 and the growth of an unprecedented ten-year housing bubble that suppressed delinquencies and stimulated the growth of a private securitization market for subprime loans.”

https://www.aei.org/publication/free-fall-how-government-policies-brought-down-the-housing-market/

When the government mandates, business follows whether or not it makes sense.

bruce, why not get your information from a source other than a political hack? aei has an agenda, and it is antigovernment. read it if you want to find material that simply reinforces your own opinion. or go read the big short to get a better understanding of what happened. the truth will amaze you!

You are going to cite the AEI as a “neutral” non-partisan observer of the financial crisis? Why not go directly to a bank lobbyist for his “objective” opinion?

I worked next to a private mortgage company during the housing boom from 2004-7. I used to run into the brokers in the elevator. They were clear that anyone who could fog a mirror could get a loan–many of their clients, recruited by an army of Spanish speaking telemarketers, couldn’t speak English but were getting jumbo mortgages via liar loans. The forms were filled out by the brokers with invented income numbers. I asked where the funds came from for the working capital to make the loans–even though they sold the loans off ASAP to the private securitization secondary market they needed some dough. I was told the working capital came via multiple steps from Wall Street.

The place was a complete fraud factory, set up to supply the private securitization market, as far as I can tell, by the private securitization market. I don’t think the Federal government’s policies had a whole lot to do with coercing these guys into this line of business.

But how do you counteract those that refuse to “take into account the negative effects of their behavior” i.e. those that borrow excessively and choose bankruptcy rather than the long, hard road of paying down debt? Since the financial crisis, I’ve seen a growing number of Americans that would rather hit the reset button and declare bankruptcy rather than exhibit discipline and go through the process (which can take some people years) of deleveraging. And the sad/disturbing part is that many of the people I’ve seen go through bankruptcy learn NOTHING from it. Once they are able to, they are borrowing again and spending beyond their means (and will likely end up back where they started – drowning in debt that they take zero responsibility for).

While some of these people might change their behavior if there was also a program put in place to educate them (and Americans in general) about personal finance, there are others who simply do not care about the negative effects their behavior has on others/the economy. It is this latter group that is most concerning and unless the proposed macroprudential regulations are in the form of some kind of hard cap on the borrowing of these individuals (any kind of “Pigouvian taxes” on these individuals for borrowing excessively is not likely to be paid, just like the money they owe on their debt) or make the bankruptcy process significantly more burdensome for them, my opinion is that you will continue to have a problem with these individuals during periods of delveraging.

MJ, as trump has indicated, bankruptcy should be simply considered as a possible business action going forward. lenders are apparently still willing to lend to possible defaulters, because they can also profit substantially from those who do not go bankrupt. over time, it appears lenders feel there is net positive gain by continuing such lending. while that group of borrows may present as distasteful to you, they appear to be insignificant in number for lenders to change their approach to the bottom line.

The discussion seems all about net debt repayment whereas the data might show mostly write-downs.

Implementing a macroprudential control system that purports to regulate excess leverage sounds like an AI challenge as well as a PR nightmare. In particular, the formulation of the control response is likely to vary in proportion to many, many system variables — more than just the individual consumers demand for credit — it must also factor in the other influential regulatory variables — e.g. local and global monetary and fiscal policy — all beyond the influence of credit-worthiness metrics.

Perhaps a finite-element analysis of the continuing global political and financial operational protocols would form the basis of a control system implementation that has the capacity to efficaciously act against a calculated but unfulfilled future risk. Measuring success would be difficult except when the need for control pressure is absent — a state of equilibrium where the control response is zero. That sounds like a real life zero-likelihood scenario. Who wants to be overtly subservient to a machine?

Raise this question — can quantitative assessment of future econometric content be adequately defined in a way that prevents perturbations when the sample rate for economic data is a calendar and thereafter subject to major revisions? Who is thereafter accountable? Maybe the computer should live in Texas.

Hooray for this post! When are people going to start thinking about ways to keep total debt amounts within what appear to be safe limits?

My fantasy at the time of Ben Bernanke’s reappointment as Fed Chair would have been for a senator to have shown him the chart of total U.S indebtedness/GDP (governmental , business, finance and household) –which showed two huge and roughly equal peaks at the Great Depression and the Great Recession–and ask him if he thought there was anything to learn from that graph. Sigh, of course that question wasn’t allowed.

Leverage kills, or at least excessive leverage damages economies. It’s odd that the Fed can’t bring itself to articulate such a point. Frankly it seems a prime case of regulatory capture.

And Mr, Hall, the U.S. Financial system does not need an intrusive government to persuade or coerce them to lend excessive amounts of money. Please look at the lending binges of the past 30 years–to Latin American sovereigns in the 1980s, to Texas oilmen in the 1970s and 1980s, to S&Ls in the 1980s, to homeowners in the 2000s, to North Dakota oilmen in the 2010s, to…etc., etc. Lenders basically pour gasoline on fires–the problem is getting them to stop.

William Meyer,

A lot of things happen in Latin and South America that don’t necessarily happen or wouldn’t necessarily happen without certain government mandates here.

And, by the way, the expansion of oil production in Texas and North Dakota were not necessarily bad loan decisions when they were made and oil prices were high. They may not be bad decisions in the long run. Certainly they made many more things more affordable in the U.S. and didn’t require $billions in government bailouts.

Hi Bruce,

Not sure what you mean about Latin and South America. Citibank (along with various competitors) was big on recycling petro-dollars from the 1970s and early 1980s oil shocks into government loans south of the border. Unfortunately, as an observer noted at the time, sovereigns have no kneecaps to break, so there were defaults. Citi was effectively insolvent and required a great deal of regulatory forebearance, including a deliberate choice by Greenspan to keep the yield curve steep for several years to allow Citi and several competitors to earn themselves back into the black. That is, if you think about it, a “stealth” bailout, and yes it did cost other borrowers substantial amounts of money to subsidize the banks.

As for the decisions to lend into oil booms, the early loans probably made sense. But you may notice that banks (and other lenders, including through the junk bond markets) have a hard time saying “no” once their competitors start announcing large profits from “booming” sectors. At a certain point, these booms then become driven by excessively available credit, rather than fundamentals (or good business practice.) Clearly this was also the case with the late lamented housing boom–except there, the problem morphed into outright fraud and what to me seemed deliberate criminal behavior.

You need to realize each of those events were influenced by different factors and economic conditions change over time. And, the “U.S. financial system” has done an enormous amount of good.

Those who blame the collapse on careless individual borrowers forget a crucial fact — who has the keys to the vaults? Who is in a position to check the bona fides of potential borrowers? Who sets the requirements to qualify for loans? For Gods sake, who made borrowers sign legal documents permitting the lenders to investigate them fully, to justify the loan?

Did these rascally borrowers somehow forge their loans, or hypnotize their loan officers, plus everyone in the chain of approval upwards?

Yes, there was a sort of “hypnosis” involved, but it wasn’t originated by the borrowers. Sheesh.

Noni Mausa,

You miss the point: those “rascally borrowers” would never have gotten the loans in the first place without the government pressuring Fannie and Freddie into making unreasonable loans. Sometimes, “equal outcomes” are nothing more than bad outcomes.

This is a revisionist tale of events. The loans in question were private. The entire lending industry was in on the scam.

Loan retailers

Bond packager

Debt ratings providers (S&P, Moody’s and Fitch)

Bond retailers

The wholesale corruption with the MERS system never made it out of a few narrowly focused blogs.

I’m sure I’m missing a bunch of interested parties that made a tonne of money on the scam.

“By contrast, macroprudential regulation discourages borrowing and keeps funds in the hands of lenders without the need to slow down economic activity.”

Without the need to slow down economic activity? This sounds not plausible. When the private debt level in the peak year would have been lower than the actual level, then the total consumption would have been lower. The same sentence indicates this: “keeps funds in the hands of lenders”.

I doubt whether the 25% lower MPC (marginal propensity to consume, the finding according to Jappelli and Pistaferri) of the rich applies. First, their figure is based on quantiles, while in reality most of the lenders to the first quantile borrowers may be “located” on the top end or even beyond the survey distribution capture. Second, only a few lenders match many borrowers, which amplifies the MPC difference. Third, the survey was done in Italy, a less unequal country than the US are. Consequently, it may become more close to true to say that borrowers who are among the poorest 10% of households are more than 50% more likely to spend an additional dollar received than *the few* rich lenders would do instead of the borrowers.