Today, we are fortunate to present a guest contribution written by Ashoka Mody, Charles and Marie Visiting Professor in International Economic Policy, Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University. Previously, he was Deputy Director in the International Monetary Fund’s Research and European Departments.

The European Central Bank (ECB) was set up as the most independent of all central banks. Its independence also made it unaccountable. Freed from public accountability, the ECB’s decisions have been swayed by its management’s ideological preferences and by national interests. The consequence is that some eurozone countries are now subject to long-term deflation risk and are locked into a currency that is too strong for their economies.

In 1991, when European negotiators met in Maastricht to decide on Europe’s single currency, two matters were uncontroversial: a future ECB would act independently of political oversight, and its only goal would be to fight inflation. These were German requirements for giving up the deutsche mark and joining the single currency. The French were unhappy but knew that if they demanded greater oversight of the ECB or required that it also boost employment, the Germans would walk away. All other countries fell in line.

In March 1997, twenty-two months before the euro’s launch, Paul Volcker, former chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve board, cautioned against the ECB’s hyper-independence. “No central bank,” he said, “could be comfortable … operating entirely outside a political context”; in a democracy, a central bank “must be able to justify its policies to the general public and to political leaders.”

Commentators paid less attention to the ECB’s exclusive focus on controlling inflation rather than balancing—as the Fed does—the dual objectives of stimulating employment while keeping inflation under check. But two Nobel laureates, Franco Modigliani and Robert Solow, warned that an obsessive focus on price stability would keep interest rates too high, which would reduce the pace of GDP growth and, hence, elevate unemployment rates. That is precisely what happened. With no public accountability, the ECB repeatedly sacrificed growth and employment, even triggering a financial crisis in July 2011, as I document in my forthcoming book, EuroTragedy: A Drama in Nine Acts.

The contrast between the ECB and the Fed emerged early. In March 2000, after the tech bubble burst, the U.S. economy slowed, which put a damper on world trade and, hence, on the eurozone economies since they depend heavily on international trade. Although the initial downturn was modest, the U.S. Fed applied the risk-management principle, and began aggressive reduction in interest rates. The American economy, Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan said, was “in the position of the person falling off a 30-story building and still experiencing a state of tranquility at 10 floors above the street.” The policy task was to build a monetary safety net to cushion the fall.

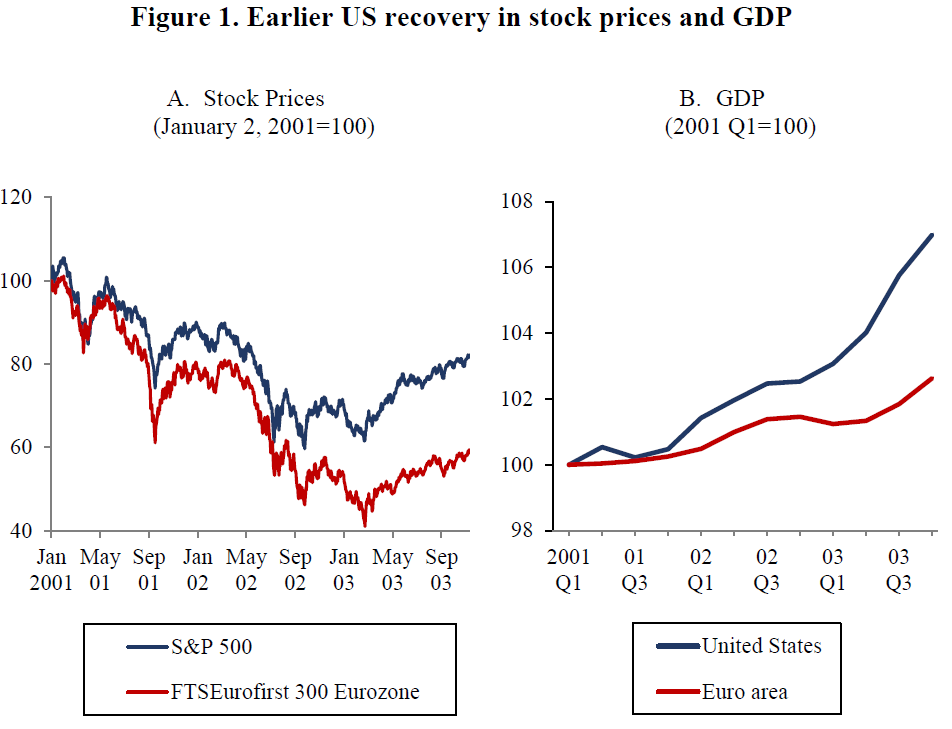

When global economic prospects suffered further after the 9/11 attacks, the economic woes were acutely felt in the eurozone. But while the Fed kept up rapid rate cuts, the ECB emphasized its inflation-fighting goal and eased interest rates at a glacial pace. Facing calls for more monetary stimulus, ECB President Wim Duisenberg infamously said, “I hear, but I don’t listen.” Predictably, recovery in the eurozone was considerably slower than in the United States (Figure 1).

Sources: FTSEurofirst 300 Eurozone (FTEUEBL(PI)) from Datastream; S&P 500 (^GSPC), online at https://finance.yahoo.com/q/hp?s=^GSPC&a=00&b=1&c=1999&d=11&e=31&f=2003&g=d. For GDP, OECD Statistics “B1_GE: Gross domestic product—expenditure approach; LNBQRSA: Millions of national currency, chained volume estimates, national reference year, quarterly levels, seasonally adjusted,” available from stats.oecd.org.

The same pattern repeated after the onset of the global financial crisis in July 2007. Some observers believe that the Fed unconscionably delayed stimulative measures. But once it initiated interest rate cuts in September, the Fed moved rapidly. Janet Yellen, then president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, articulated the risk-management philosophy. “I honestly don’t know what the risks are,” she said, but the financial disruptions could generate “negative, non-linear dynamics.” Translation: things could get ugly quickly.

The ECB, under President Jean-Claude Trichet, acted in a starkly contrasting manner. Although growth and inflation trends were virtually identical in the United States and the eurozone, and although financial stress in the eurozone was at least as great as in the United States, the ECB’s first policy action was to raise interest rates in July 2008. Only after a near global financial meltdown following the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in September 2008 did the ECB grudgingly agree to reduce its interest rate as part of a globally coordinated rate reduction.

After the Lehman episode, the Fed continued rapid monetary easing, bringing its policy rate down to near zero by December 2008, at which time it also introduced its first bond-buying quantitative easing (QE) program, designed to rapidly bring down long-term interest rates. The ECB’s plodding rate reductions were lampooned by financial markets as other central banks, especially the Bank of England, acted at a blazing pace.

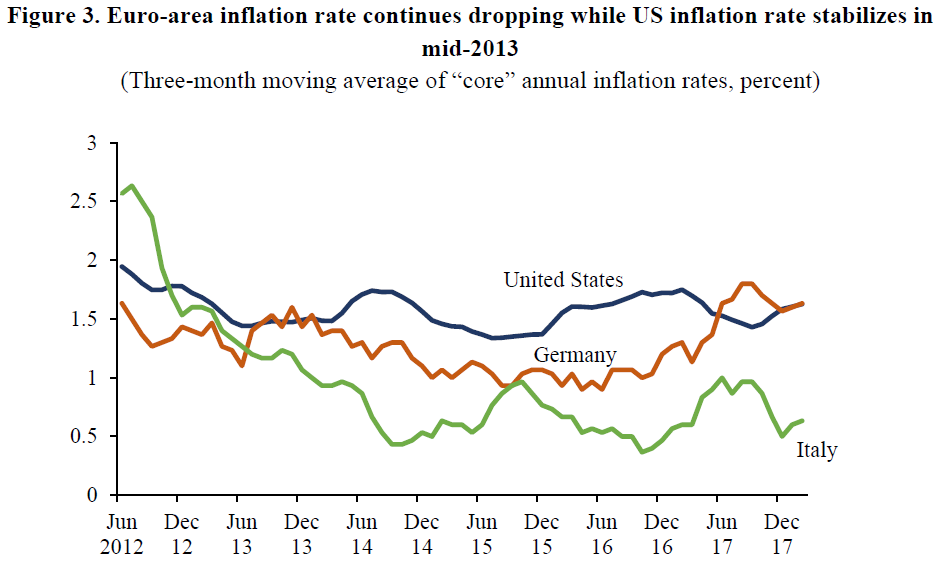

The outcome mirrored that in 2001–2003: the Fed’s stimulative policy helped the U.S. economy recover more rapidly from the global financial crisis (Figure 2).

The next phase marked an even starker divergence between the Fed and the ECB. Starting in late 2009, pulled by a massive fiscal and credit stimulus in China, the global economy began to recover. Chinese demand also caused a spurt in commodity prices, which stoked a rise in global inflation rates. The Fed recognized that this inflation spurt was temporary. Indeed, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke worried that the still high unemployment rates would cause price deflation, which would make debt burdens harder to shoulder and, hence, weaken the economic recovery. Now applying the risk-management principle to preventing deflation, the Fed announced a second round of QE in November 2010.

The ECB did the opposite. Observing the same inflation trends, the ECB raised its policy interest rate in April and then again in July 2011. These actions had near-catastrophic effects. Banks throughout the eurozone came under acute stress. In Italy and Spain, a sovereign-bank “doom” loop was triggered: the risk that weak banks would need government support created a fear that the governments themselves would be unable to honor their obligations, which amplified the anxiety that banks would default on their debts.

In November 2011, Mario Draghi replaced Trichet as the ECB’s president. The ECB reversed the Trichet rate hikes. But eurozone monetary policy was still too tight, and the promise of more monetary easing was not matched by further action through mid-2012. The eurozone financial crisis continued to spiral out of control. Italian and Spanish interest rates soared, and the governments and banks in the two countries seemed at imminent risk of default. Mario Draghi then declared that the ECB would do “whatever it takes” to prevent a eurozone implosion. Interest rates fell and the sense of crisis passed. But real interest rates—the nominal interest rates governments and businesses pay minus national inflation rates—remained positive and large in Italy, Portugal, and Spain. Businesses held back investment, and recessionary conditions continued not just in these financially vulnerable countries but through much of the eurozone.

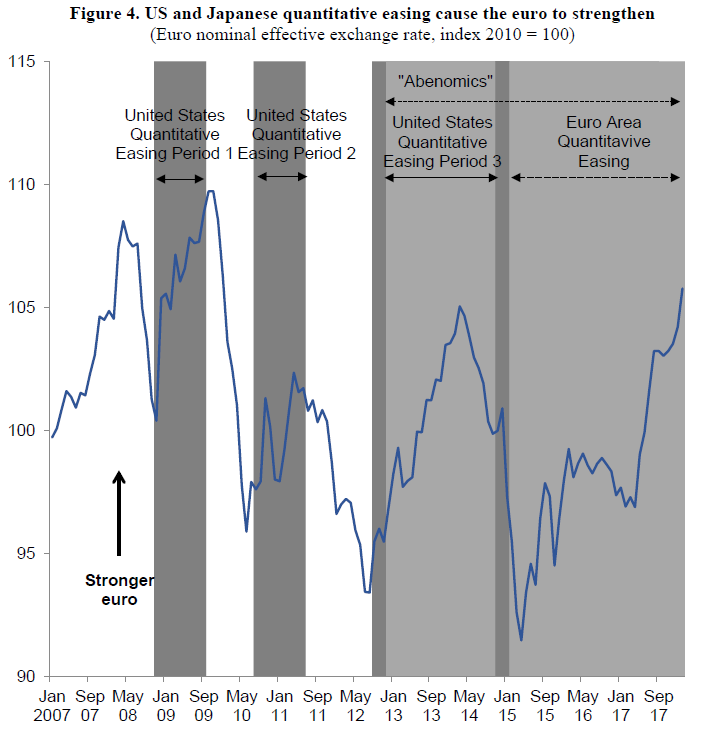

This prolonged period of crisis and recession took its toll, and by mid-2013 the eurozone began to fall into a deflationary zone. The core inflation rate—the inflation rate stripped of volatile food and energy prices—remained above 1.5 percent in the United States but began to fall toward an average of 1 percent in the eurozone. Yet, held back by German and other “northern” eurozone member country representatives, the ECB continued to delay QE. Inflation rates fell even in Germany, but—in its bid to fight a phantom inflation threat, the ECB created an actual deflation risk in Italy (Figure 3).

Source: Eurostat; St. Louis Fed, FRED: “Personal Consumption Expenditures Excluding Food and Energy (Chain-Type Price Index).”

Finally, in January 2015, with the average eurozone inflation rate stuck around 1 percent, the ECB began its QE program, six years later than the Fed. The ECB was now in a situation like that of the Bank of Japan (BOJ). The BOJ had long deployed half-hearted and short-lived monetary stimulus measures. As a result, businesses and consumers had begun to expect that prices would remain relatively flat. Once inflation expectations fell, it became rational to postpone expenditures believing that inflation might fall further, which kept inflation low and reinforced the sense that inflation would remain low. Even the massive monetary stimulus injected by the BOJ beginning in January 2013, under the “Abenomics” program to recharge the Japanese economy, could do little to raise the inflation rate.

Not surprisingly in view of the BOJ’s experience, despite continuing large bond purchases by the ECB, the eurozone’s average core inflation rate remains around 1 percent. This average hides a wide divergence across member countries. While Germany, with its stronger recovery, has regained a core inflation rate of around 1.6 percent, the inflation rate in Italy is in the 0.5–0.7 percent range.

Hence, Italy’s real interest rate is still above 1 percent, which, with its chronically weak economy, will act as a significant impediment to renewal of investment and growth. The Italian government’s debt is above 130 percent of GDP; Italian banks are still dealing with large volumes of non-performing loans. Italy is the eurozone’s fault line. By bequeathing to Italy a high real interest rate, the ECB has ensured that the tremors along the Italian fault line could easily morph into widespread financial crisis.

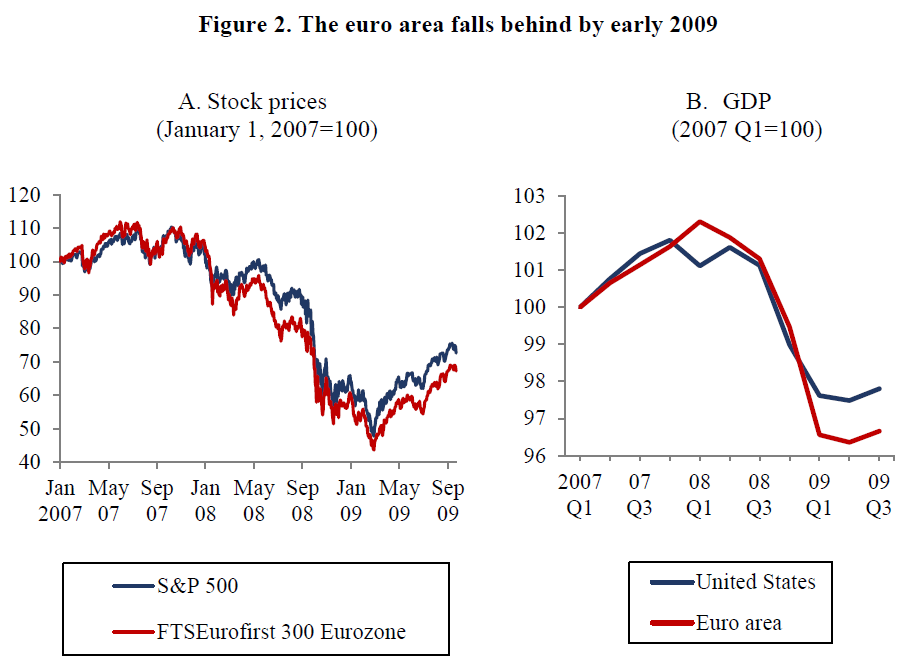

Moreover, financial markets have come to expect an ECB bias toward tight monetary policy, which has ensured a rising euro exchange value. Despite the ECB’s huge QE, the euro’s effective exchange rate is back around its level in mid-2007 (Figure 4). At that level, the euro is definitely too strong for Italy, exacerbating the country’s woes.

The ECB has never been called on, and has never offered, to give a reasoned explanation of its delays and half-measures, or even its egregious error in July 2011. Its lack of accountability has placed it between a rock and hard place. If the ECB winds down its QE, real interest rates will rise, which will increase Italy’s financial fragility. If the ECB extends its QE program, it will accumulate more Italian bonds at high prices and face the risk of large losses when it eventually sells them. The burden of those losses will then be borne by German and other eurozone taxpayers. Either way, the ECB is at risk of feeding the eurozone’s political fissures, which could quickly lead to widespread and far-reaching financial instability.

Sources: Bank for International Settlements, “Effective exchange rate indices, Narrow indices, Nominal”; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System press releases November 25, 2008, September 23, 2009, August 10, 2010, June 22, 2011, September 13, 2012, September 17, 2014; Ben Bernanke, 2013, “The Economic Outlook,” testimony before the Joint Economic Committee, US Congress, Washington, D.C., May 22; Shinzo Abe, 2013, “Press Conference by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe,” Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet, January 4; ECB press release: January 22, 2015.

This post written by Ashoka Mody.

This is a very insightful discussion starting with this lead:

“its only goal would be to fight inflation. These were German requirements for giving up the deutsche mark”.

This was my concern some 30 plus years ago. Now had I written a paper articulating this back then – I would look like a genius now. Stupid me for not doing so.

What I fine, well written, understandable, and interesting guest contribution from the obviously very knowledgeable Ashoka Mody. So much information, so much to digest.

One thought came quickly to mind, as an answer to a question from a post by Menzie a while back. Is the fact of the prolonged European Central Bank tight money policy enough to overcome the interest rate differential between the EU and the US, answering at least in part the new Fama Puzzle?

Ed

WTF? Drawing German 10 year government bond rates to make a simple point re your clearly confused understanding of what all these discussions mean?

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/IRLTLT01DEM156N

ECB used to be tight but over the last few years has been more expansionary than US policy which is why this interest rate fell to near zero over the past few years. The Fama Puzzle refers to the empirical observation that the international Fisher equivalent (IFE) was a bit off. But Menzie’s latest writings suggests IFE holds aka the low European rates did lead to the kind of Dornbusch overshooting standard international macro predicts. In a word, the Euro jump devalued augmenting the recent ECB stimulus albeit over the long-run the Euro is expected to eventually appreciate.

So much economics – so little understanding on your part. Get busy learning economics.

Really nice contribution and paper (??) by Professor Mody. And I think the blog is lucky to have him deposit some of his wisdom here.

My only question to Professor Mody would be, where the hell were you when Christine “I Love Adidas” Lagarde was meeting with Yanis Varoufakis about the Greece refinancing/restructuring?? All I saw was a light-weight (Lagarde) acting very condescending and poo-pooing the Greek Finance Minister. If the IMF was trying to use any of its considerable weight in the matter, I never saw it. What I observed, was a woman walking around with a false air of self-importance, who by her actions was more interested in protecting French banks, than in taking an ethical stand (nevermind basic human morality) against Schauble for those on the European periphery.

One’s first guess would be the IMF has no appreciation for the more clever members of its own research department???

IMHO you are a bit hard on her. She is being rather sensible for the head of the IMF which used to take the cold hearted stance you accuse her of:

http://www.ekathimerini.com/224045/article/ekathimerini/news/imfs-lagarde-says-restructuring-greeces-debt-essential

I think there is some merit in the criticism of the ECB.

However, the world entered oil shock price levels from mid-2011, and these prices sustained through H1 2014, prompting a lasting recessions in the Euro area. I would add that the notion that the ECB’s quickly reversed, 0.5 pp rate rise in 2011 caused an 18 month recession in Europe is, well, hard to believe. It is not hard to believe that $100+ oil caused a recession in Europe.

My take, with graphs, is here.

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2018/5/8/ecb-policy-versus-an-oil-shock

The comparison of the US v. ECB Federal Funds rates over time really tells the story. Thanks for this post.

What were the debt ratios? Debt is the most important variable in the equation in terms of causality on growth. Euro government debt rose from 65% in 2007 to 87% last year – up 22 pts. And falling. US debt rose from 61% to 100% — up 39 pts. And rising. Of course, this huge differential increase in debt enabled the US to grow more rapidly than the euro area over the past 10 years. No surprise here. But the above analysis takes no account of this. Why is this important? Because in both the euro area and the US, the debt ratio is far above optimal. Debt will inhibit growth going forward for a very long time. But it will inhibit euro area growth far less. Europe is already deleveraging, and has far less pts to deleverage.

The above therefore is only part of the story. And the conclusions drawn are thus questionable, though we don’t have enough data from the author to know by how much. Furthermore, the euro area and US are not strictly comparable since the states are united while the core vs periphery in Europe is a twisted knot that not only inhibits growth to some extent, but also makes above-optimal levels of debt more risky as there are multiple weak points (any number of high debt countries) in the euro area that can take the whole thing down. Greeks are mad as hornets, and arguably at some point the fabric in Europe is going to rent. Putting the entire global economy at risk once again.

Little chance that European Union will go the British way by giving up Euro and if it does a catastrophe for the whole European economy. Both Japan and European Union are in the same boat. Perhaps Japanese Central Bank is more shrewd by stealthily coming out of Quantitative Easing.

An interesting article by Dr. Ashok Mody. But US is now coming out of QE by increasing interest rates. Europe Central Bank has already halved its bond buying. Would like to know what next.