Today, we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Enrique Martínez-García (Senior Reserach Economist and Policy Advisor, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas). The views expressed here are those solely of the author and do not reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System. He acknowledges the contributions of Valerie Grossman, Michael Morris, Amro Shohoud, and Mark A. Wynne in preparing these comments.

The expectations of near-term global expansion have weakened noticeably in recent months—2019 global growth forecasts have declined from 3.9 percent in April 2018 to 3.4 percent in March 2019, while 2020 global growth forecasts (3.5 percent with March 2019 data) suggest a very modest bounce-back is anticipated next year. The 2019 forecast downgrades reflect an evolution in the global outlook, at first echoing isolated but severe contractions in Venezuela, Turkey, and Argentina, but more recently reflecting a broadening slowdown among major economies. The weakening of global industrial production and trade that began in the later part of 2018 pose additional challenges to what has already become a downbeat near-term global growth outlook.

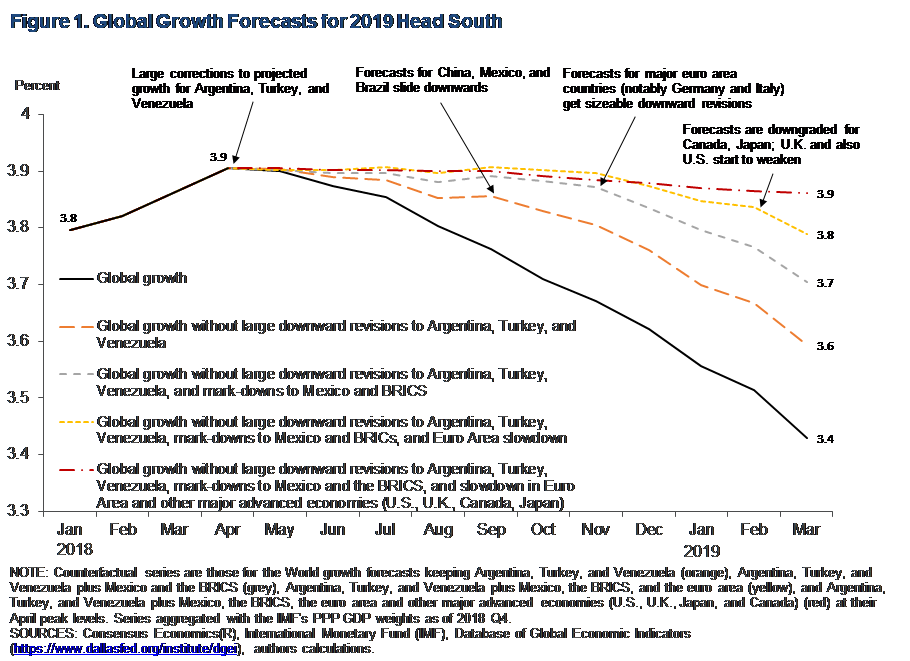

Private forecasters’ global growth expectations offer a distinct perspective on the near-term global outlook. Such forecasts for global growth can be obtained after aggregating Consensus Economics® data for a selection of 40 countries—including the U.S. and 39 other major world economies with historically strong trade ties with the U.S. The aggregates are weighted using the International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s corresponding annual shares of world GDP for each country (in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) terms for comparability). Global growth forecasts for each year can be calculated in this manner at a monthly frequency from January of the preceding year. Figure 1 below illustrates the 2019 global growth forecasts starting in January 2018 (black solid line) providing us with insight into the baseline expectations for near-term global growth among private forecasters the world over. By their estimation, 2018 global growth was expected to be 3.8 percent with prospects for 2019 slightly above 3.8 percent early on. Global growth forecasts for 2019 peaked around 3.9 percent in April 2018 and have gradually declined since then—falling to 3.4 percent by March 2019. The latest data also anticipates subdued global growth of 3.5 percent for 2020.

What’s Behind the Numbers

Looking under the hood, part of the decline in 2019 global growth forecasts shown in Figure 1 (black solid line) began to materialize early on in the second quarter of 2018. At that point, the decline reflected mostly the effects of a very large downward revision for Venezuela (whose contraction turned into an unprecedented collapse, the magnitude of which is unparalleled in peace time) and of severe recessions in Turkey and Argentina—all of which bit hard already by the summer of 2018. These three countries alone still account for approximately one-third of the fall in global growth prospects recorded between April 2018 and March 2019 (as illustrated by re-computing global growth keeping the forecasts of Venezuela, Turkey, and Argentina at their April 2018 levels as is shown in the dashed orange line in Figure 1 below).

The political crisis that has engulfed Venezuela remains unresolved and has had broader consequences—a migrant crisis and spillovers affecting oil markets. Turkey and Argentina, similarly hit by falling investor confidence and currency crises, continue to struggle to address the deep-rooted economic problems that prompted the malaïse in these countries (high inflation, large current account deficits, and an unwieldly stock of dollar-denominated debt). These negative developments in Venezuela, Turkey, and Argentina have not resulted in the knock-on effect on other emerging economies that was feared—yet their impact has been felt in parts of Latin American and Central and Eastern Europe.

More central in the international economic system, the major emerging economies—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (the so-called BRICS countries) and Mexico—started to weaken somewhat in the second half of 2018. That softening is mostly attributed to a number of unrelated factors, largely originating domestically. Most notably, it reflects a reassessment of the major economies of Latin America—particularly Mexico after a shift in policy and Brazil to some extent due to its ties to Mercosur. It also comes from a softer patch in China amid ongoing concerns about the country’s medium-term outlook, the impact of its ongoing efforts at deleveraging, and the ramifications of the U.S.-China trade dispute. The phasing out of the subsidies to cities with hot property markets for new projects to tear down and redevelop “shantytowns” and the expiration of tax cuts on single-engine vehicles also hurt the Chinese economy in the second half of 2018.

All of this has weighed on global growth (as illustrated by the dashed grey line in Figure 1 below that is computed by also maintaining the BRICS and Mexico forecasts at their April 2018 levels), while dragging down global industrial production and global trade. Further signs of weakening of the Chinese economy in the latter part of 2018 led to renewed policy efforts in recent months aimed at supporting near-term growth through a targeted approach to provide ample liquidity (particularly to small- and medium-sized enterprises) and more recently through fiscal stimulus measures including a 3 percentage point cut in the value-added tax (VAT) mostly benefitting manufactured goods.

By the fourth quarter of 2018, the economic expansion among major advanced economies began to lose some steam as well and, not surprisingly, the growth forecasts of some of them began to slide downwards (as illustrated in the dashed yellow line in Figure 1 below). The euro area—and particularly the economies of Italy and Germany—has struggled to consolidate its cyclical expansion of the previous years while being plagued by negative domestic developments as well as by increasing global headwinds.

Much of the cyclical strength of the euro area in recent months has eroded due to: the car industry slump and declining business confidence and export orders in Germany, budgetary squabbles and weak growth in Italy which have triggered a heightened country risk, the flare-up of social tensions such as the yellow vests movement (mouvement des gilets jaunes) in France, and a mixed bag on European banks’ performance, among other issues. Weakening trade within the euro area (Italy) and among other important trading partners (Turkey, but also crucially China) is weighing down on the economic performance of export heavyweight Germany with ripple effects elsewhere in Europe.

The fears of a global slowdown are starting to bite more widely—including some retrenchment in North America (even for the U.S.) and the U.K. (whose prospects had remained fairly stable through the uncertainties arising from their negotiations to withdraw from the European Union (Brexit), but are now diminishing along with the prospects of their key trading partners in the euro area) (as seen in the dashed red line in Figure 1 below), among others. High-frequency data also paints a similar picture—that of broadening subdued momentum in the first quarter of 2019. Indeed, outside the U.S., industrial production and global trade growth have noticeably slowed.

Why It Matters

The global outlook for 2019 has turned out to be one of diminished expectations. Global growth is projected to stabilize at 3.5 percent in 2020—yet, part of the strength in those numbers is due to the anticipation of major turnarounds in Argentina and Turkey plus the hope that the worst of the negative economic consequences of the Venezuelan crisis can be mitigated in time. However, without those forecasts materializing, global growth may end up slowing in 2020 below the 3.4 percent currently forecasted for 2019.

Some of the policy uncertainties (U.S.-China trade disputes, Brexit) may get resolved and asset market and exchange rate volatility could remain subdued. Other domestic and global risks can (re-)emerge during 2019 too—not the least those related to or connected with the path of monetary policy normalization and the anchoring of inflation expectations in major advanced economies, to mention just a couple of the uncertainties and global headwinds looming large in the immediate horizon. This could further dim what has already become a downbeat near-term global outlook. Oil markets continue to be rattled by geo-political turmoil (Venezuela, Libya, and Iran to cite but a few) while rapidly being transformed by the shale boom that began in the early 2000s, largely centered in the U.S.

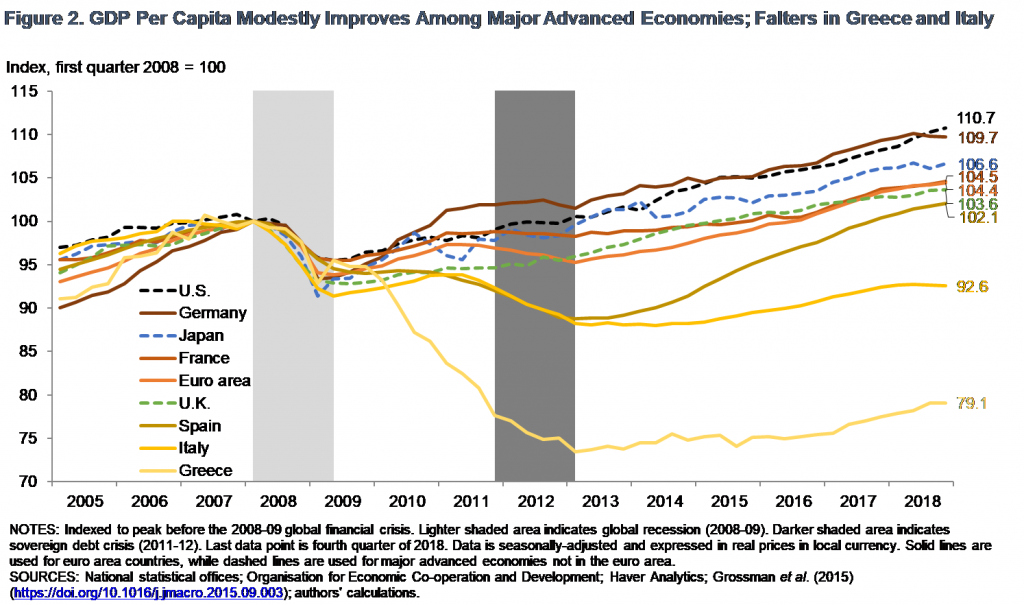

Entrenched low inflation in some advanced economies (notably Japan and the euro area) has indeed soured the mood on the global outlook. The risk of low inflation arises because below-target inflation expectations can become entrenched and heighten credibility concerns for monetary policymakers. Moreover, other longer-term challenges continue to shape the global outlook conditioning its near-term path along the way—among them, financial concerns related to corporate indebtedness in the U.S., China’s rebalancing towards its domestic demand and the slowdown in global trade, and low potential growth have been prominently cited. As for the latter one, the slow recovery of pre-2008 standards of living among major advanced economies has been further complicated by the limited real convergence within the euro area, accentuated in the aftermath of the 2008-09 global recession (as seen in Figure 2 below). In fact, Italy and notably Greece endured a lost decade having gained little ground in real GDP per capita terms since before the 2011-12 euro area sovereign debt crisis.

How 2019 will turn out will greatly depend on how policymakers, households, and firms respond to the current short-term global economic slowdown while seeking to curb risks to the outlook and raise potential long-term growth prospects. Keep track of the quickly evolving global economy with the latest indicators from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas’ Database of Global Economic Indicators (DGEI).

This post written by Enrique Martínez-García.

Great article and solid writing by Mr Martinez-Garcia and friends. Enjoyed the links. I am not 100% certain, but I think the very last link for the Dallas Fed DGEI may be incorrect. Maybe an innocent typo or something. Double check that.

Great job though and I’ll be doubling back over those links and gnawing on the graphs a little more. Great late night reading, thanks.

Moses Herzog: Link to DGEI is fixed, thanks.

“How 2019 will turn out will greatly depend on how policymakers, households, and firms respond to the current short-term global economic slowdown while seeking to curb risks to the outlook and raise potential long-term growth prospects.”

With Trump firing everyone and then hiring more yes men (and women I guess) I’m sure we will do great! All kidding aside, it looks like the US and Germany both did best in terms of recovering from the 2008 recession. But how could that be with the US being led by that Kenyan socialist Obama? Trump needs to fire everyone at the Bureau of Economic Analysis!

It’s said that “RT” was created to sow seeds of distrust with American citizens towards our government and our media. I’m certain that’s true. Still, I’m left wondering if we don’t give “RT” all of their best material without Russian propagandists having to put any thought or effort into it at all:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rkjqn2pvqLA

I’m rather astonished at the emphasis on Venezuela as a cause of the slowdown. A tiny economy that is ranked at 64 for GDP by the IMF? At a time when when there is a glut in oil and prices near record lows?

joseph,

Also Argentina and Turkey. Also note that oil prices are no longer near record lows. Brenc Crude is back up above $70 per barrel, more than twice the low from not too long ago. As iit is, the collapse of Venezuela has become really severe. One observer calls it “the worst economic disaster ever in Latin American history.”

Also Argentina and Turkey.

I understand that it’s not just Turkey per se, but the exposure of already shaky Italian banks to Turkish debt.

Well its GDP fell from $550 billion in 2013 to only $330 billion in 2018 by some accounts. Oil represents around 20% of this economy so the fall in oil prices had a yuuuge even on Venezuela. Thankfully for them, oil prices have recovered somewhat.

But their economy is still crashing hard, despite that, blackouts and other fullout disasters.

But, yeah, could be even worse.

This is a pretty AMAZING graph if you ask me. These are the type things it unceasingly bewilders me do not get more attention and don’t actually even grab major headlines. Look at the times if the recessions and the peaks of those graphs. This is why I believe credit markets are often the big tip-off on recessions. And I dare you to argue with me while looking at that graph. Courtesy of Mr. Martinez-Garcia and his links:

https://www.dallasfed.org/research/economics/2019/~/media/Images/research/economics/2019/0305/0305c1.png

Notice how when donald trump’s AG is asked if he’s given donald trump an early peak at the contents of the Mueller Report, Barr immediately shuts down and says he’s not answering the question. Why refuse the question if he hasn’t given donald trump an early look at the contents??

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k00GxD92hXM

*early peek

Michael Brabant, in my personal opinion one of the best video journalists on planet Earth. Not a telegenic man, but an outstanding journalist:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5w0WoeMsd8U

A man whose Jewish family immigrated to America from Belarus in the early 1900s, now a proud Nazi. Who knew??

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yY180duyenU

How should we describe Stephen??? A Schmuck??? Khnyok?? Amoretz?? Kadokhes?? נאַר ?? Or should we list Stephen as we sometimes say in English, “all of the above”??

Anyone who knows Yiddish who disagrees with me this man Miller is a disgrace of a human being and a racist?? Speak up now or remember to smile later when Miller decides you’re in the next group to get trodden on or have your children kidnapped and put into cages by ICE goons.

Dear Folks,

Might the fiscal and monetary policy-makers respond to this by easing policy? Isn’t that what Trump is trying to do?

J.