PBoC and financial regulators act, but even with fiscal measures underway, are unlikely to drastically change the path of the economy.

As summarized by Bloomberg:

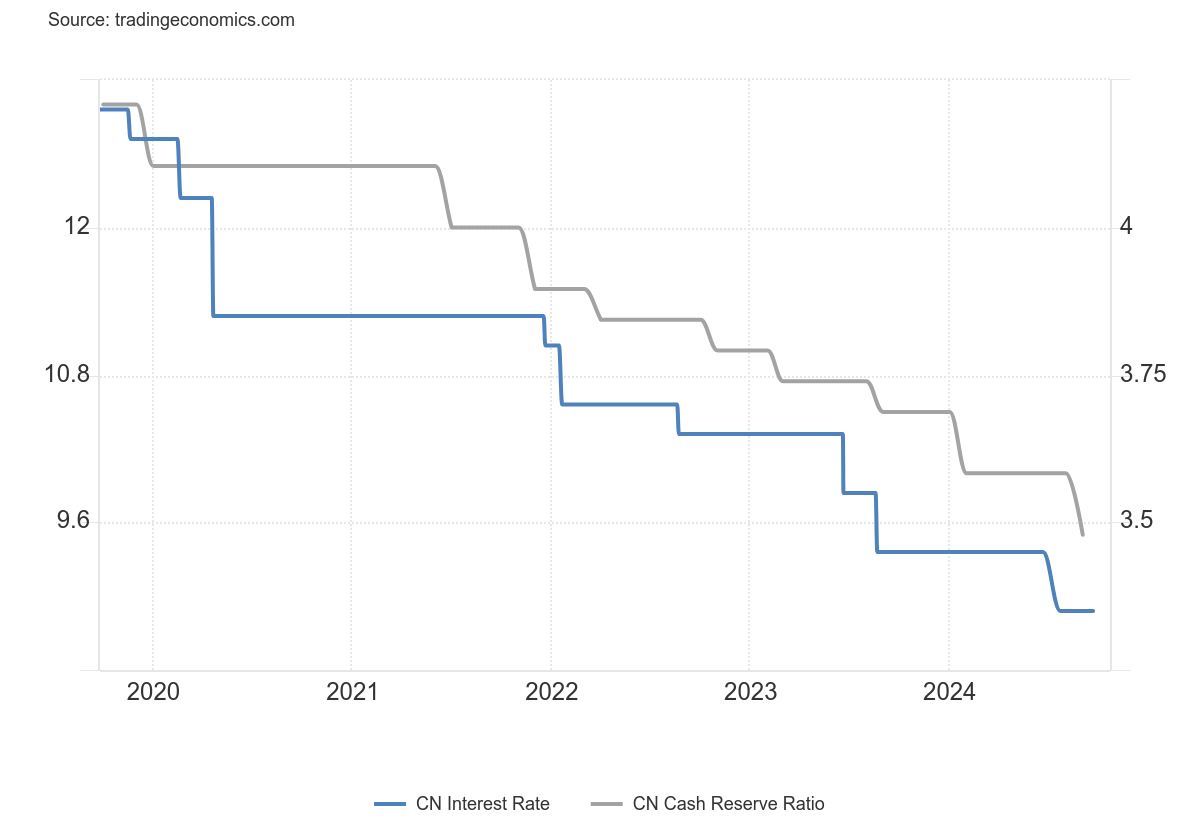

- People’s Bank of China Governor Pan Gongsheng announced a cut in the reserve requirement ratio, seven-day policy rate and existing mortgage rates, in a bid to both boost lending and reduce the existing loan burdens. He said further RRR cuts are possible

- Pan also announced at least 500 billion yuan ($71 billion) of liquidity support for stocks. There will be a swap facility allowing securities, funds and insurance companies to tap the PBOC to buy stocks. Pan also told reporters that authorities are studying setting up a stock stabilization fund, without details

- China Securities Regulatory Commission Chairman Wu Qing said new measures to encourage mergers and acquisitions will be unveiled soon, and underscored the CSRC’s work to improve regulatory oversight. National Financial Regulatory Administration chief Li Yunze said China will add tier-one capital to six major commercial banks.

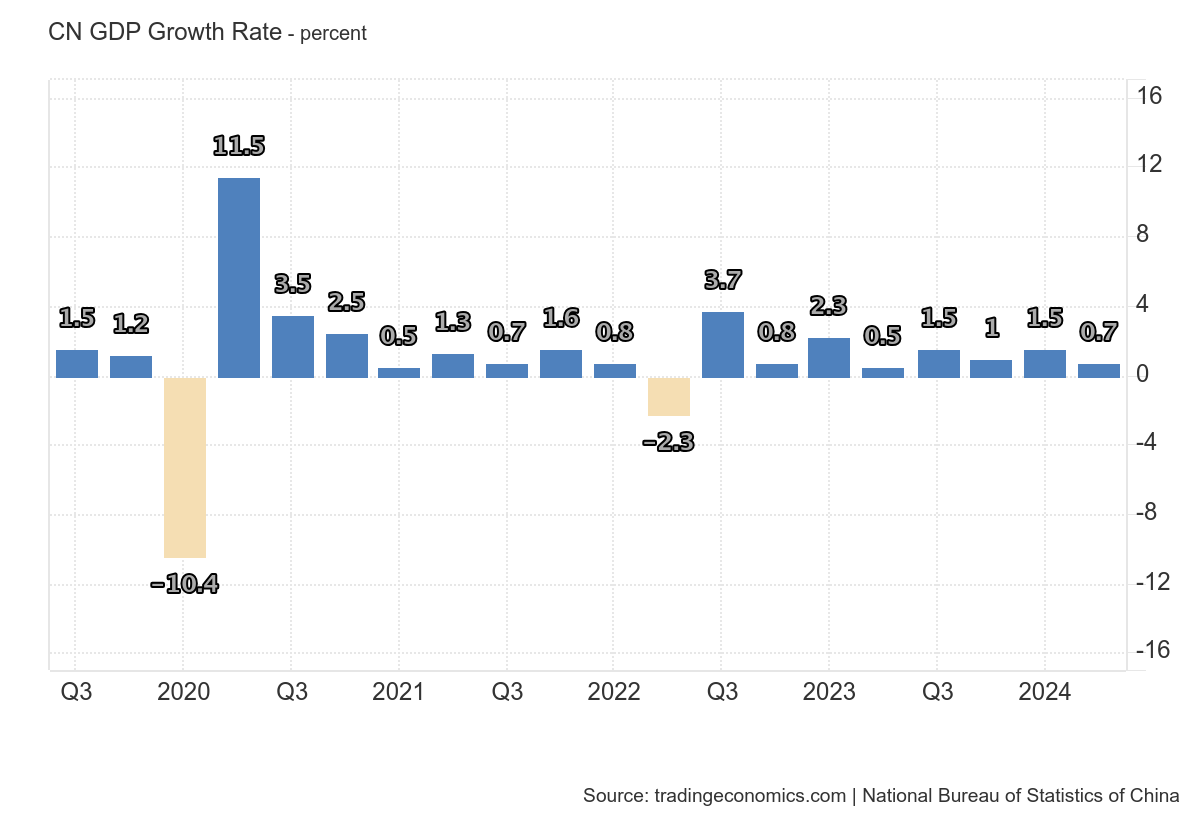

To me, it’s curious it took so long, then followed by a flurry of activity in the last 48 hours preceding the announcement. I have no particular insights into the workings of policymakers under the current regime, so I’ll let others debate the sources of delayed action. However, here are some macro indicators that show the need for some action — decelerating growth, and deflation. First GDP growth (q/q SA):

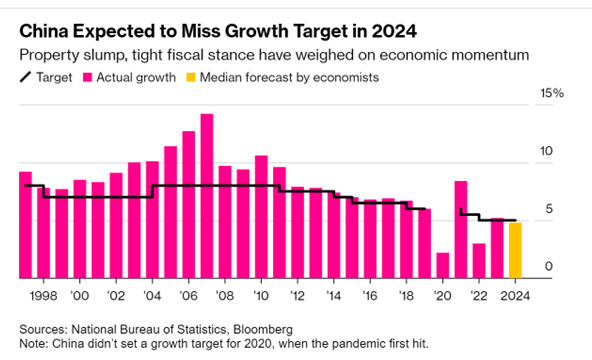

Taken at face value, 0.7% q/q is 2.8% annualized(!). There were doubts that under previous set of macro and regulatory policies, the 5% target (y/y I think) would be hit.

Source: Bloomberg, 24 Sep 2024.

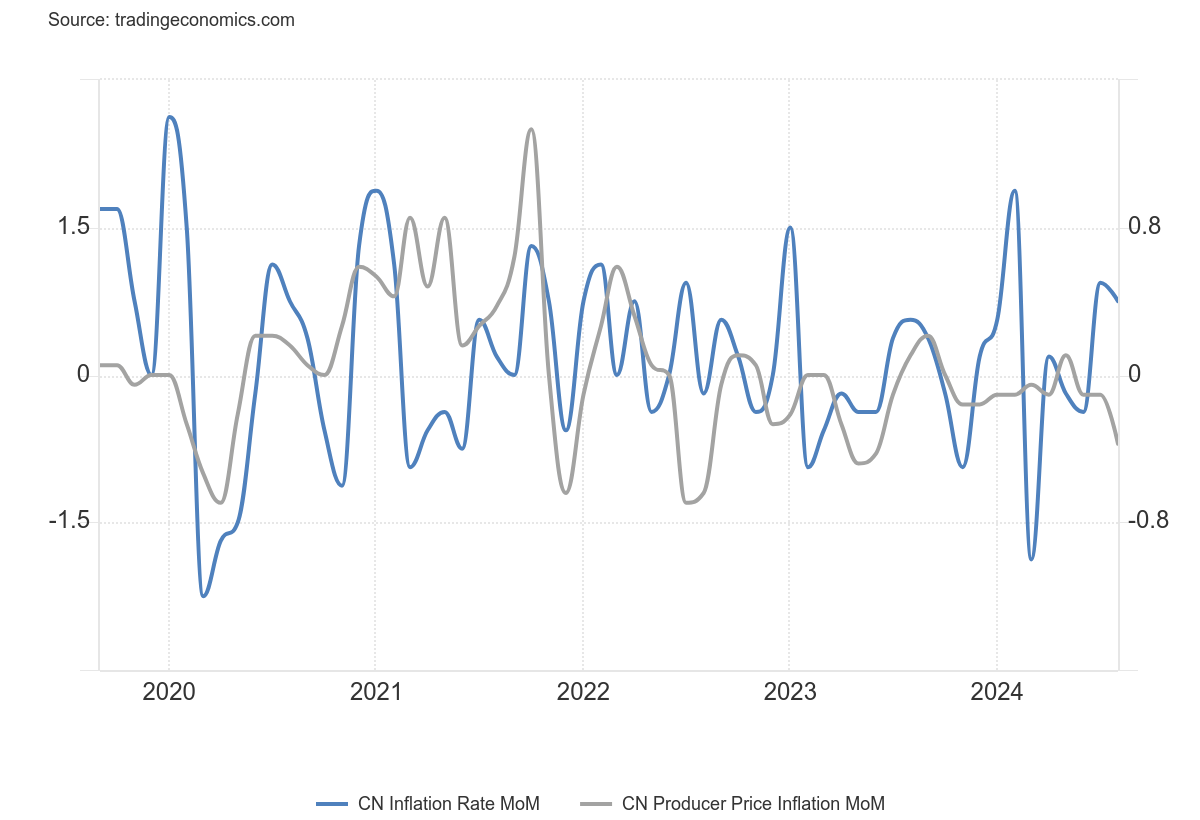

Second, deflation. More worrying in some ways is the decline in prices — not in the CPI but at the producer level, and for the economy overall. CPI and PPI m/m inflation rates (note difference of scales, left vs. right axes). Deflation can be a signal of slowing growth, as well as exacerbating demand shortfalls.

So while consumer prices have risen in recent months, producer prices have fallen. As noted in the Bloomberg article, the GDP deflator has also fallen, for five straight quarters (-3.8% 4 quarter change as of Q2).

The quandary is shown in the decomposition of GDP:

Source: Garcia Herrero & Xu, Natixis, 13 Sep 2024.

Despite the fact that the above is a mechanical decomposition (an accounting identity), one can still make some inferences about the constraints to growth. Consumption is the main contributor to growth – but consumers are reluctant to spend in the wake of the collapse of the housing sector. Deflation makes debt more burdensome (think of the financial accelerator). Net exports could contribute more to GDP, but with the surge in Chinese exports already eliciting trade barriers not only in the US, but also in Europe, it’s hard to think of a big increment coming from additional net exports.

What will fix things? It depends what “fix” means. Return to +5% growth? Or just continued growth without collapse. I think the consensus view is +5% growth is off the table. So avoiding a full-blown crisis, with hopefully positive growth rates is the goal.

Eswar Prasad notes the need to accelerate productivity growth (which affects the long run, but — depending on how implemented — also the short run via expectations):

Recognizing the need to improve productivity and shift away from low-skill manufacturing, the government recently articulated a “dual circulation” growth policy, which augments continued engagement with global trade and finance with greater reliance on domestic demand, technological self-sufficiency, and homegrown innovation. But the approach has run into difficulties. China still needs foreign technology to upgrade its industry, and rising economic and geopolitical rifts with the United States and the West could limit China’s access to foreign technology and hi-tech products, as well as to markets for its exports. Moreover, the government’s recent crackdown on private firms in sectors such as technology, education, and health has had a chilling effect on entrepreneurship.

The ongoing decline in inward FDI suggests there’s been no reversal in the conditions for FDI into China – unsurprising given the Xi administration has not really changed the overall economic framework, including “dual circulation”. (Of course, FDI into China might have also occurred because of attempts to friendshore, as well as the prospect of restrictions of governmental restrictions on outbound FDI).

So, don’t look for a quick fix. And expect even less, if the Xi administration continues to place primary weight on political dominance versus GDP growth (see e.g. Arthur Kroeber ).

Timing? Well, perhaps announcement of new stumulative policies was somehow linked to the disappearance of a top economist:

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.business-standard.com/amp/world-news/top-chinese-economist-vanishes-after-remarks-against-xi-in-private-chat-124092400809_1.html

This is how you get Xi’s attention. When private talk isn’t enough, you speak in public, get yourself arrested, and then everybody knows that Xi has been told. The critic is punished for his courage, but Xi acts.

Whether the policy action is adequate isn’t important. Xi had to do something. This is something.

This isn’t some special Chinese pattern of behavior. It’s as common as dirt. Xi’s entire career is about making his own power permanent. Illegitimate power looks just like this.

Incredibly hard to watch. Not just the wasting of but perennial throwing into the garbage bin of a lot of high-quality human capital.

I believe >80% of China’s college educated (certainly what I think they refer to in English as “key universities”) “know the score”, know what is happening and how ass-backwards it is. Yet can do nothing for reasons Macroduck has just enumerated.

I had intended to include this link in my above comment but it slipped the sad contraption I call my brain:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Key_Universities

The similarity of circumstances in China now to Japan’s Lost Decade and to the U.S. (developed country) real estate bubble is hard to miss. Policy can improve the situation, but cannot make it go away. China hasn’t even come to the end of falling asset prices yet; “scarring” is still in process. China still has to go through a long period in which scars to the economy slow growth.

Here’s a look at total factor productivity in the U.S.:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/RTFPNAUSA632NRUG

There was a decade-long stall in TFP growth between 1973 and 1983 – y’all know why. During the Great Moderation, TFP grew fairly steadily, then stalled and began to fall during the housing bubble. It continued to fall through the housing collapse and has grown at a slower pace since. That slower pace is a message for China.

China has a real estate collapse, trade restrictions, souring demographics, mal-investment through much of the economy. The absolute smartest, most forward-looking policy is needed to mitigate these problems. Policy-making which requires brave souls to get themselves arrested in order to do anything at all is useless.