I’m taking the WSJ’s word for it, from the article “Russia’s War Economy Shows New Cracks After the Ruble Plunges”.

The Russian economy, surprisingly resilient through two-plus years of war and sanctions, has suddenly begun to show serious strains.

The ruble is plunging. Inflation is soaring, and President Vladimir Putin told the Russian people this week that there isn’t any reason to panic.

The catalyst for the change in economic fortunes was a decision by the Biden administration to ratchet up sanctions on Russia’s Gazprombank, the last major unsanctioned bank that Moscow uses to pay soldiers and process trade transactions, as well as more than 50 other financial institutions.

While official statistics have certainly depicted a surprisingly resilient Russian economy, there are definitely questions regarding it’s true strength (remembering that “Potemkin village” is a term originating from that country). First the plunge in the ruble indicates the tradeoff that is being made between defending the currency, staunching inflation and keeping the economy growing.

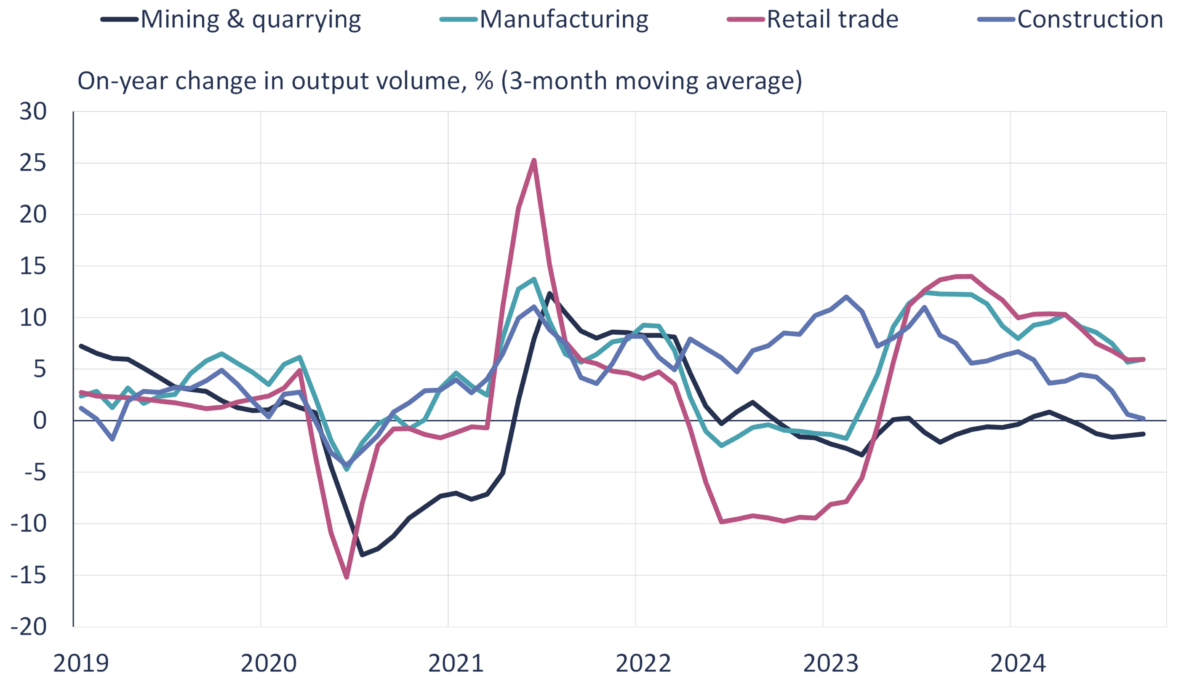

Bofit, a week ago, highlighted the deceleration in y/y growth:

Russian GDP growth slowed significantly in the third quarter

Rosstat’s preliminary estimate puts Russian GDP growth in July-September at 3.1 % y-o-y. GDP growth has slowed significantly this autumn. All core sectors have shown weaker growth in recent months compared to the first half of this year.

The slowdown in GDP growth has largely been driven by pressures from the mining & quarrying and construction sectors. On-year output of mineral extraction industries (includes oil & gas) has fallen in recent months, while on-year growth in construction is practically zero. Agricultural output also contracted in the third quarter. GDP growth has still been supported by manufacturing and retail sales, but growth has slowed also in these branches. Manufacturing growth, in turn, has been driven mainly by industries related to war.

Here’s their graph, using official statistics:

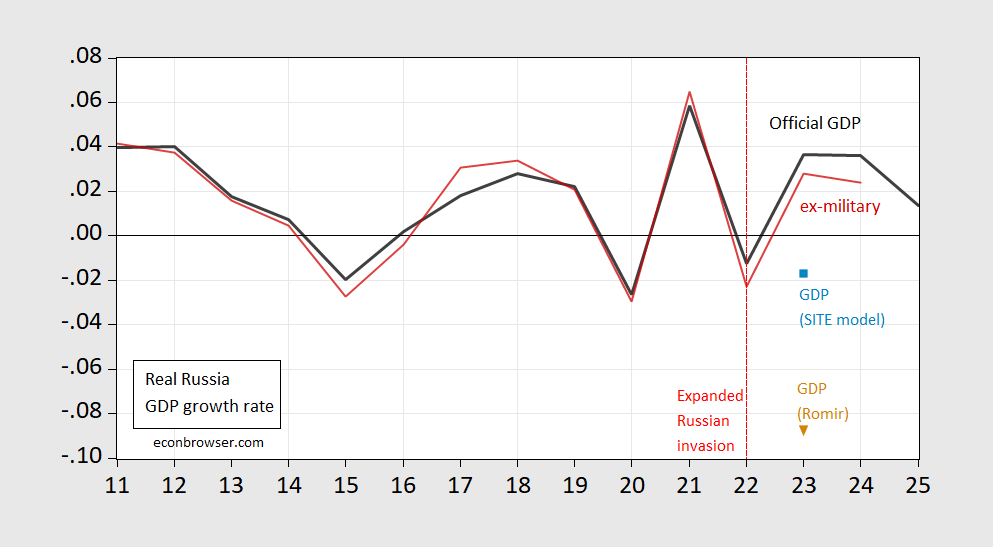

Finally, let’s think about the plausibility of Russian statistics, and also what GDP measures. First, compare official GDP to official GDP ex-military spending (as estimated by SIPRI):

Figure 1: Official Russian GDP growth (black), official GDP ex-military spending growth (red), Russian GDP using SITE oil-based model (light blue square), official GDP using Romir price index as deflator (tan inverted triangle). GDP ex-military spending calculated using nominal values, deflating by overall GDP deflator. Source: IMF October 2024 WEO, SIPRI database, SIPRI, SITE (Figure 26), and author’s calculations.

The strong growth looks less strong when deducting outright military expenditures (note that capital costs associated with defense spending, along with other internal security operations, would not be included in SIPRI’s estimates of military expenditures).

In addition, the Stockholm Institute of Transition Economies, in it’s recent report on the Russian economy, provides several alternative estimates of Russian GDP growth. I show two estimates: (i) one based on a simple econometric model linking oil prices to Russian GDP, and (ii) nominal GDP deflated by the Romir price index (see this post).

Russia’s earlier relative strength was partly the result of full employment and the rise in wages it caused. However, with so much of Russian production going to the war effort at the expense of consumption goods, those wages are probably a considerable source of inflationary pressure. Russia’s main trading partner under sanctions is having a tough time – China’s weakness could well be a contributing factor in Russia’s weakness.

The decline in oil and mining output is consistent with tepid conditions in the petroleum market world wide:

https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/oil-faces-uphill-fight-demand-woes-oversupply-challenge-opec-efforts-2024-11-29/

China is certainly a factor in slack oil demand. India, on the other hand, is a growing source of demand for Russian energy products. India is apparently turning Russia’s isolation to it’s advantage in other ways, producing technology products for the Russian military. It’s a shame about India’s turn toward seedy ethnic politics, because it’s looking like one of the healthier big economies, with reasonable prospects to maintain that good performance, Adani’s recent troubles notwithstanding.

Russia’s under-investment problem can only worsen while the central bank is fighting inflation and the military is jumping to the front of the line for financial and material resources. The war in Ukraine is going Russia’s way lately, but this is looking like a Pyrrhic victory if ever there was one. Sucks to be them, even if Trump kisses up to Putin from day one.

According to Russia’s statistics agency, Rosstat, the price of potatoes has gone up 74 per cent since the beginning of the year (Potatoes are a staple of Russian diet for those outside St Petersburg and Moscow.) Everything is fine according to Putin – also Putin said Trump is very smart (although elsewhere on Russian media Trump is mocked and belittled – wink, wink). IMO – Putin has destroyed Russia’s economy for a generation – maybe they should switch production of 155 mm artillery shells to butter production.

Menzie – interesting misuse of statistics by an academician to support a GOP talking point – https://ritholtz.com/2024/11/lee-ohanians-comedy-of-errors/ (BTW – the federal minimum wage was set at $7.25 per hour in 2009. – )

The business of Ohanian repeatedly making gross errors is curious. The guy has a PhD and teaches at UCLA. Not realizing that a data series is NSA is a rookie mistake – or worse. I think we may have another culture warrior masquerading as an “expert’.

Oh, and there’s this:

https://americafirstpolicy.com/team/leeohanian

But shouldn’t the main takeaway be that there is no collapse happening?

In other words, anyone banking on Russia being forced by its economic conditions to stop fighting, or be lured by removal of sanctions into providing concessions in any negotiation over the war, is likely just indulging in wishful thinking?

Also, might you opine on the IMF and World Bank both upgrading Russia’s 2023 PPP GDP above that of both Germany and Japan?

“…there is no collapse happening?”

Well, that’s the question, isn’t it? One question, anyway.

The weakness of the ruble, the increase in central bank rates, the rise of inflation, the decline in output in several sectors all are symptoms of general economic deterioration. I don’t have a handy definition of “collapse”, but what’s happening ain’t good for Russia. If our only concern is the outcome of the Russia’s attack on Ukraine, then collapse, however defined, is of primary importance. If Russia’s ability to continue to threaten its neighbors and the wider region is also a concern, then the potential for collapse is far from the only issue.

As to reshuffling an ordering of GDP rankings, that doesn’t change reality. It only changes our perception.

Weakness of the ruble probably doesn’t mean as much now as it did in April 2022 since you would have expected adaptations to be less dependent on imports by now. PPP teaches us not to be too focused on exchange rates when discussing a country’s productive capacity. It sure seems that over the past near-3 years the tendency is to underestimate Russia’s capacity and overestimate the economic and manpower damage it is incurring. People then become too optimistic that Russia cannot continue to finance the war, and act as if Ukraine still has the ability to turn the tide. This would be a serious mistake IMO.

Jason: It’s not that the ruble’s value has dropped is in itself affecting lots of things; rather it signals the choices policymakers face – inflation vs. growth.

Don’t see any signal at all from the exchange rate given how much thinner and OTC-based the ruble currency market has become. Inflation versus growth was already settled in inflation’s favor with the rate increase to 21% in Oct.

Speaking of Russia and war and such:

“German intelligence chief Bruno Kahl says that Moscow’s acts of sabotage against Western targets could spur NATO to invoke Article 5 defence clause.”

https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2024/11/28/russias-hybrid-warfare-may-trigger-nato-defence-clause-germany-says

In addition to sabotage, Russia has announced a relaxation of its rules for the use of nuclear weapons. Not what ya do if you think you’re in a strong position.

Both sides are engaged in signaling of willingness to escalate, showing teeth and bristling. How likely any of the threats are to be carried out, I don’t know, but I know signaling when I see it.

Russia’s improved performance on the battlefield and deteriorating economy, a new government in the UK, the approach of Trump’s inauguration, Germany headed for election in February, France’s government divided all make this a time for testing and for increased odds of big changes in Europe. Heck, the BBC reported today that Syrian insurgents have been biding their time since Russia’s renewed invasion of Ukraine, anticipating that Russia will be to occupied their to be of much help to Assad, so we may already have seen one big change, not in Europe.

“Everything will be fine.”

Of course it will be fine. Putin has installed his pet poodle in the White House. Sanctions will be relaxed.