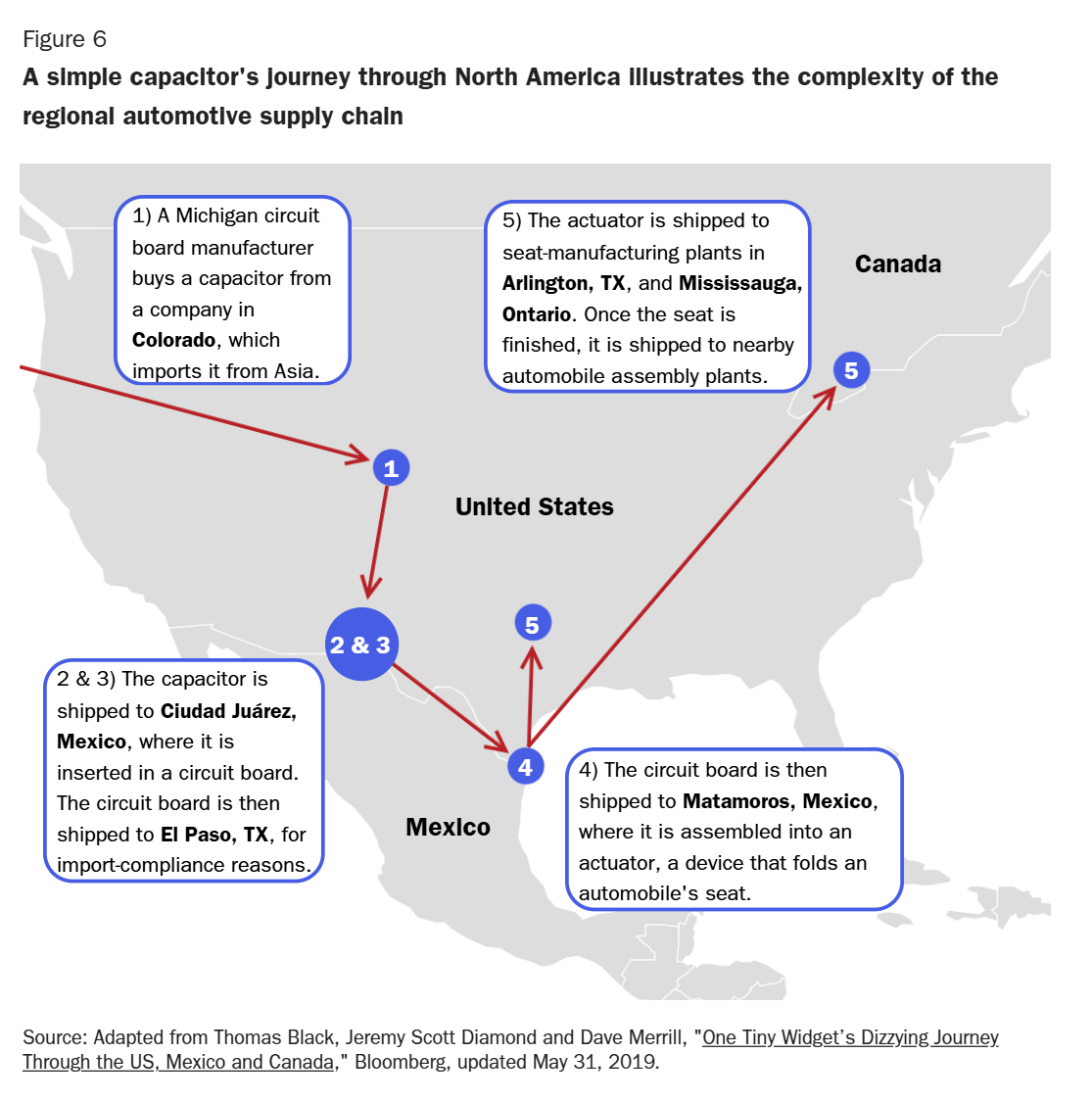

The White House has confirmed imposition of tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China tomorrow (Feb 1). Why are tariffs on Canada and Mexico different than (some) other tariffs? Consider this graph courtesy of Bloomberg via Torsten Slok:

I can’t see how production to domestic firms can be accomplished overnight, so presumably in the short run, firms will run down their inventories of stockpiled parts (maybe why goods imports were so high in December). But over the span of a couple months, that backstop will fail…

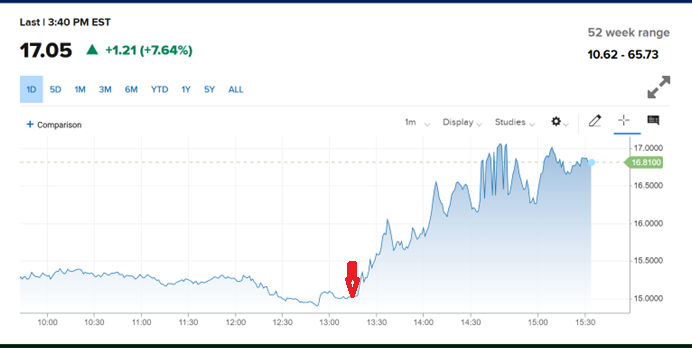

Wall Street reaction, as summarized by the VIX.

Canada has signaled retaliation of some sort.

*Apologies to Barry McGuire.

A few things ought to happen in the data as a result efforts to front-run tariffs. We should expect to see a rise in imports (a drag on GDP) and inventories (a boost to GDP) from the point at which firms saw a risk of tariffs until the end of January. Yesterday’s GDP data showed nothing unusual in Q4, which is contrary to a good bit of recent reporting, data and anecdotes:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1Dk7j

The first release of GDP data for any quarter relies on estimates for trade and inventory data, so perhaps we’ll see more evidence of front running when Q4 data are revised.

Assuming firms have stocked up on imported (mostly intermediate?) goods from Mexico, China and Canada, we would next expect to see a drop in imports as excess inventories are run off while waiting for tariffs to come back down. That would give the impression that tariffs have “worked” more than they actually have. That decline in imports would be built into pro-tariff demagoguery for ever after. Distortions of GDP data would depend on the relative response of imports and inventories in any particular quarter.

The above-described pattern is all about timing and tactics, all pretty short term. There is also a production decision to make involving intermediate goods, as indicated in Slok’s graphic. As tariffs increase the cost of imported parts, what do firms do? They can raise prices, which is likely to reduce the quantity of goods bought. They can reduce margins to avoid raising prices – choosing between higher margins on fewer units or lower margins on more. They can cut costs elsewhere. They can do some combination of the three. Each of these responses amounts to a loss of income, as has been widely discussed. GDP growth slows as a result of tariffs.

A good bit of research into the likely economic effects of tomorrow’s tariffs is summarized here:

https://taxfoundation.org/blog/trump-tariffs-impact-economy/

The overwhelming consensus is that prices will be higher and growth weaker as a result of tariffs.

Research at the Fed has found that manufacturing jobs were lost as a result of tariffs during the rapist-in-chief’s first term:

https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/disentangling-the-effects-of-the-2018-2019-tariffs-on-a-globally-connected-us-manufacturing-sector.htm

If we suffer output losses this time, as expected, then we are also likely to suffer more job losses.

Just a reminder – factory employment was higher at the end of Biden’s term than at any time during the felon-in-chief’s first term:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1Dk8l

So Trump puts 25% tariffs on our allies Mexico and Canada but only 10% on China. Gee, this wouldn’t have anything to do with Musk’s critical business investments in China, would it?