Today, we’re fortunate to have Willem Thorbecke, Senior Fellow at Japan’s Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) as a guest contributor. The views expressed represent those of the author himself, and do not necessarily represent those of RIETI, or any other institutions the author is affiliated with.

President Trump imposed tariffs on imports from China that rose to 145% by April 9th. Then on April 11th he exempted imports of smartphones, computers, semiconductor devices, and other electronics imports from these tariffs. The White House said the exemptions were granted to give time to move factories back to the U.S. How do tariffs affect electronics exports and how could production be relocated to the U.S?

Investigating How Tariffs Affect China’s Electronics Exports

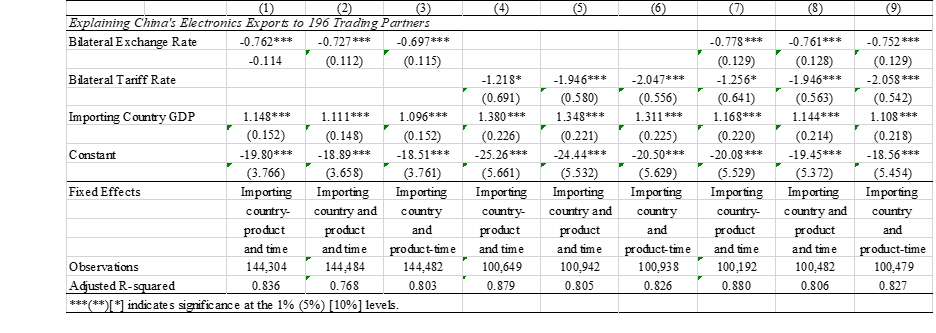

In recent work with Chen Chen and Nimesh Salike, we investigate how tariffs affect China’s electronics exports. To do this we use the methodology of Bénassy-Quéré et al. (2021). They explained annual disaggregated bilateral exports using a series of fixed effects, the bilateral real exchange rate between exporting and importing countries, the natural logarithm of one plus the bilateral tariff on a product, and other variables. We employ data on China’s bilateral real exports disaggregated at the Harmonized System four-digit level for 44 categories of electronics exports to 196 trading partners over the 2003 to 2018 period. These products include computers, telecommunication equipment, semiconductors, semiconductor manufacturing, testing equipment, software, scientific instruments, and associated parts and accessories. We use the electronics goods that are included in the Information Technology Agreement.

The findings are presented below:

The results indicate that a 10% appreciation of the Chinese renminbi would reduce electronics exports by between 7% and 8% and that a 10 percentage point increase in the tariff rate would reduce electronics exports by between 12% and 21%. The higher response of exports to tariff changes than to exchange rate changes is an example of the international elasticity puzzle. Despite the fact that tariffs and exchange rates should have the same impact on exports in many trade and international macroeconomic models, researchers have found that tariff rate changes affect exports more than equivalent exchange rate changes. If the U.S. does impose tariffs on China’s electronics exports, it would cause a large decrease in exports.

How Did East Asia and China Become Leading Electronics Exporters?

Although tariffs will reduce China’s exports, they cannot ensure that production relocates to the U.S. During the first Trump Administration, Foxconn responded to the threat of tariffs by agreeing to build a liquid crystal display manufacturing plant in Wisconsin.[1] It signed a deal with the state of Wisconsin to build a factory that could employ up to 13,000 people and Wisconsin offered $3 billion in subsidies. Instead of building the promised 20 million-square-foot factory, Foxconn constructed an empty building one-twentieth that size. It employed only 281 people, and many played video games or watched Netflix because they had nothing to do. Foxconn let employees go after receiving subsidies for hiring them. Foxconn received subsidies exceeding $400 million but never constructed a working fab.

How did East Asia build a vibrant electronics industry? Incentives played an important role. After World War II, Japan was forbidden from making military products so companies like Sony and Sharp focused on consumer electronics. Because competition in consumer electronics was intense, entrepreneurs such as Akio Morita at Sony and Tadashi Sasaki at Sharp faced incentives to master technologies in order to reduce costs and differentiate their products. If they failed, their firms would go bankrupt. In the semiconductor industry, U.S. firms were coddled by lucrative defense contracts while Asian firms remained lean producing chips for low margin products such as calculators and televisions.

Taiwan initiated semiconductor manufacturing in the 1970s in the midst of a crisis. It had to leave the United Nations in 1971 when the U.S. established diplomatic relations with China. It severed relation with Japan in 1972, losing a key supplier of technology and capital goods. In 1974 it faced quotas on textile exports and it suffered a 47% increase in consumer prices between 1972 and 1974 due to the energy crisis. It also confronted the threat of invasion from China. Economic development and industrial upgrading were essential for survival. This galvanized government officials, entrepreneurs, and workers.

Taiwan valued education. In 1968 it instituted a nine-year compulsory education system when few countries had nine-year requirements and later extended this to 12 years. It also recruited Chinese engineers who had Ph.Ds. from U.S. universities as well as seasoned Chinese researchers at U.S. semiconductor companies. Educated workers are more adept at learning new technologies. In addition, as Ricardo Hausmann has emphasized, much manufacturing knowledge is latent and stored in workers’ brains. This tacit knowledge grows glacially, and it is easier to move brains than it is to move knowledge into brains. Taiwan benefitted from professionals such as Morris Chang coming to Taiwan as well as from experienced engineers returning home. Through trial and error they developed world class companies such as United Microelectronics Corporation and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). Although the government initially subsidized these companies, eventually they had to sink or swim in global markets.

After China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, Chinese companies followed in the footsteps of Japanese and Taiwanese companies. They focused on catching up by first imitating foreign production methods and then by innovating. China constructed superb networks of modern highways, ports, and airports. This helped to attract foreign direct investment, and Chinese workers and firms learned from foreign firms. Chinese firms also serviced the very demanding Chinese domestic market. Companies such as Huawei viewed efficiently solving their customers’ problems as the highest goal. This forced them to innovate, and in 2018 Huawei submitted 5,405 intellectual property applications to the World Intellectual Property Organization. This ranked first among global multinational corporations.

Lessons for the U.S. from Asia’s Electronics Industry

Entrepreneurs drove much of Asia’s success. Tadashi Sasaki at Sharp, Akio Morita at Sony, Morris Chang at TSMC, and others were visionary leaders. They took risks with no guarantee of return. If their firms did not satisfy consumer preferences, then their companies would cease to exist and they would lose their jobs. Western CEOs in the electronics industry are often rewarded whether or not their risks pay off. Nokia CEO Stephen Elop presided over the annihilation of Nokia and left with a 24.2 million euro payoff. Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger earned

$179 million in his first year at Intel even as the company’s stock price tumbled. If the U.S. wants to reshore manufacturing, it is essential that entrepreneurs face appropriate incentives.

An educated workforce is also necessary for assimilating technologies. In Asia, this includes a high quality education in science and math at the secondary school level and technical or scientific training at the university level. In the 2022 OECD Programme for International Student Assessment exams, the performance of US students in math was the lowest ever. In addition to technical training, Japan was most successful at electronics when its engineers also received a broad liberal arts education including literature, philosophy, and history. If the U.S. wants to succeed in electronics manufacturing, it needs to improve its educational system. It is also essential to attract workers from abroad who have tacit and experiential knowledge in manufacturing.

High quality infrastructure is also required. This includes highways, ports, airports, and ICT infrastructure. The American Society of Civil Engineers gave U.S. infrastructure a grade of C in 2025. While this is better than the C- grade that U.S. infrastructure received in 2021, it still indicates the need for better infrastructure. China initially could not establish strong infrastructure networks across the whole country so it built these in key locations such as the Pearl River Delta and the Yangtze River Delta. This led to many firms agglomerating there, generating economies of scale and profitable interactions between upstream and downstream industries. If the U.S. wants to reshore production, it should consider first improving infrastructure in key locations.

As the experience of Foxconn in Wisconsin illustrates, it is important not to overestimate what tariffs can do to promote manufacturing. The incentives facing entrepreneurs are important, as are promoting learning and improving infrastructure. Other lessons for strengthening electronics manufacturing in the U.S. are discussed in Thorbecke (2023).

References

Bénassy-Quéré, A., Bussière, M., Wibaux, P. 2021. Trade and Currency Weapons. Review of

International Economics 29, 487-510.

Dzieza, J. 2020. The Eighth Wonder of the World. The Verge. October 19.

Thorbecke, W. 2023. The East Asian Electronics Sector: The Roles of Exchange Rates,

Technology Transfer, and Global Value Chains. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge,

UK.

[1] This paragraph draws on Dzieza (2020).

This post written by Willem Thorbeck.

“If the U.S. wants to reshore manufacturing, it is essential that entrepreneurs face appropriate incentives.”

Sir! Would you drive a stake through the heart of American capitalism? Good day to you, sir! I say, good day to you, sir!

Timely work, good piece.

Along similar lines, in recent years, NATO and in particular European countries have discovered that building out a defence industrial base does not occur at the snap of the fingers.