Do we have any idea what the CNY appreciation against the dollar will accomplish?

Most of the analyses of how the Chinese currency’s valuation affects U.S. imports from and exports to China, rely upon guesstimates of the relevant trade elasticities. There is a small empirical literature.

Mann and Plueck (2005) [pdf] investigate disaggregate China-U.S. trade. Using an error correction model specification applied to disaggregate bilateral data over the 1980-2004 period, they find extremely high income elasticities for US imports from China: for capital and consumer goods the estimated long run income elasticities are 10 and 4, respectively. The consumer good price elasticity is not statistically significant, while the capital good elasticity is implausibly high, around 10. On the other hand, US exports to China have a relatively low income elasticity of 0.74 and 2.25 for capital and consumer goods, respectively. The price elasticity estimates are not statistically significant. In general, they have difficulty obtaining sensible coefficient estimates.

Willem Thorbecke (2006) [2005 version here as pdf] examines aggregate bilateral US-China data over the 1988-2005 period. Using both the Johansen maximum likelihood method, as well as the Stock-Watson (1993) dynamic OLS methodology, he finds statistically significant evidence of cointegration between incomes, real exchange rates and trade flows.

US imports from China have a real exchange rate elasticity ranging from 0.4 to 1.28 (depending upon the number of leads and lags in the DOLS specification). The income elasticity ranges between 0.26 to 4.98. In all instances, substitution with ASEAN trade flows is accounted for by the inclusion of an ASEAN/Dollar real exchange rate. Interestingly, the income elasticities are not statistically significant, even when quantitatively large. For US exports to China, he obtains exchange rate elasticities ranging from 0.42 to 2.04, and income elasticities ranging from 1.05 to 1.21.

One issue encountered by Thorbecke is the issue of appropriate deflators. He deflated the trade flows by the U.S. CPI. This imposes the condition that the bundle of goods and services imported from China is the same as the bundle exported from the U.S., and is the same as the bundle consumed by the typical U.S. household.

In order to investigate the issue further, I, along with my coauthors Yin-Wong Cheung and Eiji Fujii, pick up where I left off in my post on measuring U.S.-China trade flows: using a combination of actual U.S. deflators for imports from China and manufactured imports from non-developed countries for U.S. imports, and using the U.S. capital goods export deflator for exports to China. The resulting series (in log terms) are shown in the figure below.

Figure 1: U.S. imports from China (blue, red) and U.S. exports to China (green), in December 2003 constant dollars. Deflated using non-industrial country manufacturing import price index, and Chinese-sourced imports price index for imports, and capital goods export price index for exports. Source: BEA/Census via Haver for trade flows, and BLS.

I rely upon the standard imperfect substitutes model (discussed here [pdf]) as starting point. In this approach, exports are an excess over goods devoted to domestic consumption. To allow for the substitution between goods sourced from other markets, I add in an exchange rate against other currencies. Finally, in the standard approach, the supply curve of exports is assumed to be perfectly elastic, and fixed. I relax this assumption by allowing the supply curve to shift downward with supply capacity, proxied by the Chinese capital stock, as measured by Chong-En Bai, Chang-Tai Hsieh and Yingyi Qian, “Returns to Capital in China,” (2006).

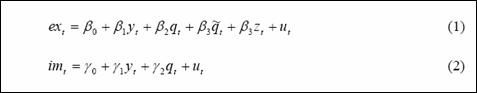

Where ex is bilateral exports from China to the U.S., im is bilateral imports to China from the U.S. (measured by the U.S.), y is an activity variable, q is a real exchange rate, q-tilde is an effective real exchange rate, and z is a supply side variable.

Using an error correction model (ECM) on quarterly data for each trade flow (with first difference terms to account for short run dynamics), I obtain the following estimates. In the long run, for Chinese exports to the U.S.,

- Each one percent increase in U.S. real GDP induces a 1.5 percent increase.

- Each one percent increase in the Chinese capital stock induces a 1.6 percent increase.

- Each one percent depreciation in the real (CPI deflated) CNY against the USD induces 0.23 percent increase; however this estimated coefficient is only significant at the 20 percent marginal significance level.

- Each one percent depreciation of the CNY against China’s trading partners (holding the USD/CNY exchange rate constant) induces as 0.15 percent increase. This coefficient is not statistically significant, although the imprecision in estimate may be due to the collinearity between the bilateral exchange rate and the trade weighted exchange rate.

- Deviations from the cointegrating equilibrium result in 81% closing of the gap within one quarter.

In the long run, for U.S. exports to China,

- Each one percent increase in Chinese real GDP induces a 1.8 percent increase.

- Each one percent depreciation in the real (CPI deflated) CNY against the USD induces 1.0 increase, which is counterintuitive. However, this estimate is statistically insignificant; the standard error is 1.47.

The exports ECM involves one lag of the first difference terms, while the imports ECM includes two lags. Lag lengths are selected such that the residuals do not reject a Box Q-statistic test for serial correlation at the 10% level (4 lags). The long run coefficients are not sensitive the inclusion of a time trend in the former ECM, while they are very sensitive in the latter case.

More than the standard caveats apply to these estimates. The trade data are mismeasured due to accounting for re-exports through Hong Kong, the deflators are not specific to the flows, the composition of the trade flows are (parts and components versus “ordinary” trade) is not accounted for, and the real exchange rate measure incorporates consumer, rather than producer, prices. Overarching these issues is the fact that for most macroeconomic issues, bilateral trade flows are of little consequence. Indeed, preliminary estimates suggest that total Chinese exports to the world do respond significantly and with near unit elasticity. We plan to examine the aggregate response in subsequent work. In this sense, these results do not directly inform the debate highlighted the day before yesterday by Brad Setser.

Keeping in mind these caveats, the upshot of the bilateral results is that to the extent that we can measure the elasticities, the point estimates imply small directly trade-relatedeffects of USD/CNY changes – so small that the Marshall Lerner condition does not hold. On the other hand the taking the extreme bounds defined by the 2 standard errors surrounding the point estimates, one finds that the sum of the absolute value of the price elasticities is about 2.56, which does satisfy the Marshall-Lerner conditions. Of course, with U.S. imports so much greater than exports, the improvement of the trade balance in response to a appreciation of the CNY against the USD is likely to be muted, even under these very optimistic conditions. (For contrasting results based on trade shares, instead of trade quanta, see Marquez and Schindler (2006).)

This is why I suspect the biggest impact of greater flexibility in the USD/CNY exchange rate would be the impact on reserves accumulation and the associated purchases of U.S. Treasury securities. Reduced demand for dollar denominated assets would result in higher interest rates and hence lower U.S. absorption. In other words, the indirect effect is likely to be more important than the direct effect.

Technorati Tags: trade deficit, China, Renminbi, Marshall-Lerner condition, and elasticities

Hi Menzie,

Your last paragraph confused me. It would seem to me that the change in the bilateral trade deficit should, roughly speaking, equal the change in the relative bilateral accumulation of reserves. Capital account + Current Account=0. Am I missing something?

jfund: China can acquire dollars from exports to other countries besides the United States, since a large amount of international trade is invoiced in dollars. Private capital inflows and official reserves transactions need to offset the current account; private capital inflows would probably also be denominated in dollars. Finally, although not often done, active reserve management can diversify the reserve portfolio out of the allocations obtained from inflows. For discussion of such matters, see numerous posts by Brad Setser.

I understand the 3rd party and official/private distinction. Something still strikes me as not quite right. Any dollars acquired by China through a 3rd party do not influence the sum of public and private sector holdings of US assets outside the US from the US’s perspective – it is just a transfer between two foreign holders. Unless these 3rd party countries are re-exporting to the US (e.g., Hong Kong), this should have no net impact on accumulation of US assets abroad.

Next, if net good/service trade does not change much then the sum of net official reserve accumulation and net private capital flows can not change much either.

The gross level of trade in assets could, however, fall. This would still be consistent with your story if the US reduced private sector investment in China (e.g., FDI based on expected returns in China plus expected yuan appreciation) while China reduced reserve accumulation in the US. Is this what you were envisioning?

Active reserve management strikes me as an important but separate issue.

I forgot to mention. I’ve read much of what you have written academically and think your research is great. Your insights are novel and useful and you express them very clearly. You bridge a difficult gap between academic insights and direct practical relevance.

jfund: Thanks for the compliment. Hopefully I can live up to your expectations. Here is my take on why RMB flexibility would be helpful indirectly to reducing the U.S. current account deficit.

Greater RMB flexibility requires less PBoC purchases of U.S. Treasuries. The RMB might appreciate a little, but as indicated by the estimated elasticities, the bilateral U.S.-China trade deficit will only be marginally affected. However, smaller purchases of U.S. Treasuries means the dollar declines against a broad basket of currencies (not just against the CNY) inducing expenditure switching against goods from all countries; at the same time, reduced demand for U.S. Treasuries places upward pressure on U.S. interest rates, further depressing U.S. consumption. Both of these effects work to shrink the aggregate (that is multilateral) U.S. trade deficit.

Econosfera

* Felicidade e Crescimento Econômico: é possível sim. * O bom e velho Smith. Não o Dr. Smith, mas Adam Smith. * China e EUA…e as elasticidades. * Mais um exemplo do que é rent-seeking. * Bens de Giffen: filhos?…

Thanks for this fine post. (Obviously I am not following this blog as closely as I should.) One possibly important point about the M-L condition in US-China trade: the best we can hope for is to estimate marginal changes in the dollar-RMB xrate, but the size of the imbalance suggests that we may be in store for a non-marginal correction. It is an act of faith to extrapolate from the first to the second. For instance, there may have been a hollowing out of production capacity in sectors that might otherwise have sustained US export growth over a large adjustment. There is also the composition effect to consider on the import side.

Of course, this is a multilateral trade issue too, and not just a question for China/US alone.