In a post over a year ago, I observed that the relative stability of the dollar would come to an end as a confluence of events occurred. Those would be the end to rises in the US interest rates, and the continued increases in policy rates abroad, especially in the euro area and the UK, against a backdrop of a massive current account deficit that requires large and continuous infusions of saving from the rest of the world (and indeed consumes most of the world’s excess saving).

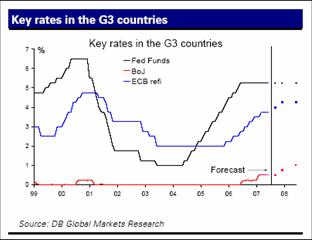

Figure 1 depicts the trends in policy rates, as well as the forecasted rates (by Deutsche Bank as of 22 June).

Figure 1: Policy rates in US, Japan and Euro area, and Deutsche Bank forecasts. Source: DB, Exchange Rate Perspectives, 22 June 2007.

My prediction was largely vindicated on this point; the dollar has taken a beating and most prognosticators do not see an obvious floor to the value of the dollar, at least against a basket of currencies (1.40 USD/EUR is sometimes cited as barrier). In euros and in trade weighted terms, the dollar has broken long-time barriers.

Figure 2: USD/EUR exchange rate, average of daily figures. Up is dollar depreciation. Source: Federal Reserve Board via FRED II.

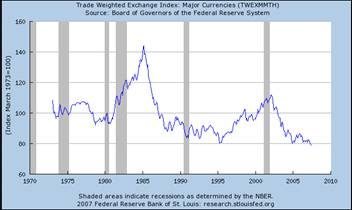

Figure 3: Nominal trade weighted value of dollar against narrow basket of major currencies, average of daily figures. Up is dollar appreciation. Source: Federal Reserve Board via FRED II.

What I did not incorporate into that prediction, but alluded to in other posts, is the idea that dollar denominated assets might become less desirable — holding asset returns constant — vis a vis assets denominated in other currencies. One way in which this could occur is via shifts in reserve accumulation. This is occurring, although the extent is difficult to gauge.

A flavor of the unfolding drama can be drawn from this FT article of 11 July:

Greenback humbled by concerns over US economy

By Michael Mackenzie in New York

Published: July 11 2007 20:27 | Last updated: July 11 2007 20:27

The dollar’s slide this week to multi-year lows against a number of currencies has come amid a fresh wave of concerns about US economic growth and the sustainability of foreign investor appetite for US assets.

With the Federal Reserve maintaining a steady overnight interest rate and many other central banks continuing to raise rates, the US currency has become less attractive to international investors. This helps to explain why the dollar has fallen to multi-decade lows against the pound and the Canadian, Australian and New Zealand dollars.

The trend intensified on Wednesday when the euro hit a record high of $1.3784 to the dollar and the pound hit a 26-year high of $2.0363.

The yen hit its best level against the dollar for a month, suggesting that investors could be unwinding carry trades, in which they borrow the low-yielding yen to invest in higher-yielding assets.

The catalyst for this latest dollar weakness is concern that the US consumer, for years the mainstay of the economy, could be flagging. Such worries followed evidence that the US housing market still does not appear to be finding a bottom along with news that retailers are suffering.

Subprime mortgages extended to borrowers with risky credit histories were again in the spotlight this week. On Tuesday, rating agency Moody’s downgraded subprime-backed bonds, while Standard & Poor’s placed $12bn of such debt on notice of downgrade, sparking further selling of US corporate bonds and widening premiums, or spreads, for derivatives protecting against default.

“One reason why the dollar has responded in such a negative fashion is that corporate bond inflows have made up half of the current account financing in the past year,” says Alan Ruskin, chief international strategist at RBD Greenwich Capital. “Wider US credit spreads are a dollar-negative event.”

In the 12 months to April, the US received $509bn in corporate bond investment inflows that helped finance the current account deficit.

The latest downturn in the dollar against the euro could have further to run, according to analysts.

…

From the above description, it is clear the prime driver of the re-evaluation of the desirability of dollar denominated assets is now the increasing perceived riskiness of bonds associated with the collapse of the sub-prime mortgage market.

Will this be the beginning of the hard landing? In the models I teach to my students, “hard landings” do not occur in well-functioning open macro-economies. As dollar denominated assets become less desirable, the exchange rate depreciates, US interest rates rise, and the economy adjusts to these new relative prices. Sharp asset price changes are possible, but they can be completely rational in nature.

However, when times are unusual, smooth adjustments might be derailed by interactive effects. In other words, the world might be nonlinear when financial markets are stressed. The particular nonlinearity I have in mind here is the interaction between higher required interest rates on dollar denominated assets necessary to attract capital inflows, and the already fragile private bond markets. Without greater knowledge of how hedge funds are positioned, it’s hard to say what will happen. But it is exactly situations like this — where the financial markets are poised between stability and volatility — that the previous experience with large US current account adjustments (such as that recounted by Croke et al. (2005), or Freund and Warnock (2005)) is of limited relevance.

Technorati Tags: dollar,

reserve accumulation,

euro,

trade-weighted exchange rate

How often do your models incorporate pegging of currency at a loss for long periods of time?

One thing we can say for certain is that we live in “uniquely interesting times”.

“Nonlinearity” … discontinuous events … one for the record books

These words and phrases have been sliding into and out of my focus for several days.

And just a moment ago, a line from an old W. C. Fields film from many decades ago (perhaps ‘The Bank Dick’) slid in…”I went up to Philadelphia the other day, it was closed.”

Perhaps not so silly as it seems should we wake up one morning and discover that a couple of ‘tier one’ firms are unable to settle.

Let us not forget that a successful act of terrorism, or a natural disaster, can be just the key the market needs to open all the cages and let the bulls and bears mix it up without the normal inertia.

Old Einstein’s relativity is at it again. Is the dollar sliding against the Euro and pound or are they appreciating against the dollar? Does it make a difference? You bet it does, and that is one of the lessons of the Great Depression that is still lost on many.

All currencies have been depreciating since 2002 but around the end of the first quarter 2006 the monetary authorities began to get a handle on worldwide inflation and all currencies began to declined. (This is difficult to see in FX markets because the currencies moved more or less in tandem.) The dollar has been dropping lately, but the longer range trend seems to be pretty stable for the dollar. On the other hand the pound and Euro are still appreciating. So….

Recently the EU has increased rates and seems to be in the posture to continue. The US is holding stable. World economies are nervous because everyone feels the central bankers are just begging to raise interest rates. At the present time that would be exactly the wrong move because it could be the event to push the economies into recession. The US should look not just at the FX rate but at currencies relative to commodities (gold anyone) and stay the course. If Euroland wants to deflate, let them.

I wrote:

…authorities began to get a handle on worldwide inflation and all currencies began to declined.

Sorry, typo, declined should be “recover.”

But it’s primarily the Euro against which the dollar falls, and imports from Europe must be only a few tens of percent of the total, at most. We can be sure the Japanese will take prompt action to ensure any significant rise in the yen is transient, and we know the yuan is not going to rise to any meaningful degree.

So how is this really relevant?

As Brad Setser likes to ask, a tipping point against what? The dollar hasn’t moved all that much against the likes of the yen, yuan, GCC currencies, etc. In other words, those countries running huge surpluses with the US.

That said, the tipping point will likely be triggered by a geopolitical event. Perhaps China actually unloading, say, $20 billion of its $1.33 trillion reserve stash as punishment for US actions against it on trade. Don’t bite the hand that feeds. It won’t be fun, but something will eventually end America’s jihad on fiscal sanity.

The question is how long China and other emerging economies will accept high food and energy inflation before reaching for the obvious cure: revaluation.

In Argentina, an antarctic blast of cold air is forcing the government to choose between price controls and heating homes. If it loosens price controls, inflation will “un-anchor”. Or it could revalue, in which case the rise in energy prices will be cushioned by a dollar devaluation. China faces the same choice, as does India, whose Rupee is on the march.

The bottom line is if headline inflation is not a problem for the Fed, it certainly is for politicians in emerging markets. Just ask an Argentine voter how it feels to have no heat when its 25 degrees.

I’ve asked it before and I’ll ask it again: why isn’t the yen at something like 80 to the dollar? If the dollar is so weak, why does it buy 120 yen (or whatever it is today)?

The Chinese have an obvious peg. The Japanese have a peg, they just won’t admit it.

And 120 yen per dollar is way, way too low. Toyota might still take over the world at 80 yen, but it will be much, much more difficult.

knotRP: Most models are symmetric, in terms of allowing for reserve accumulation/decumulation, although of course reserve decumulation is bounded from below at zero.

esb and Anchoku: I think the concern regarding the unrealistically thin spreads between riskless and risky assets over the past few years reflects the fear that somehow market participants have discounted risks too much. If there were no institutional rigidities (marking to market, restrictions on asset holdings by risk class, etc.) then mis-calculations of this sort would not be worrisome.

DickF: Sorry, I must be missing something. How can all currencies by depreciating? In any event, the trade weighted dollar is depreciating in both nominal and real terms, against both a broad and narrow basket of currencies (the nominal, narrow index is shown in Figure 3).

jm: Year-to-date (May), 21% of imports are from Europe, while 25.7% of exports are to Europe (on a Census basis). Even ignoring the relative importance of Europe, the nominal rigidity of some bilateral exchange rates would matter to the extent that sterilization is incomplete, and that prices are flexible in the long run. (In other words, in the long run, we are all monetarists now). In this sense, I agree with David Pearson‘s point.

Emmanuel: No argument from me. Although, as the number of plausible triggers increase, the likelihood of a discrete break due to any factor increases, I think.

Buzzcut: The yen is weak in part because of the systemic financial sector difficulties it had over the previous decade and half. With the concurrence of the USG in 2001, Japan engaged in a zero interest rate policy (ZIRP). A weak yen is entirely consistent with a negative interest differential with respect to other countries, and a modest level of economic growth in Japan.

DickF is exactly right. For the last year or so, vs. gold, the dollar has actually been stable. This is becuase the US has high-enough real interest rates to keep it so. Recently the Euro and Pound have been rising relative to gold. The yen has fallen.

While reduced reserve-building (more likely than a dumping of dollars) by central banks overseas would make the dollar fall relative to those currencies (like it should), ironically, the higher interest rates in the US that result could actually strengthen the dollar vs. gold (and other currencies).

This is similar to what played out in the late 80s. Look at the chart. After the big move down from 1985-1987, it traded in a channel. During the period between 1987 and the recession in 1990, interest rates rose, the price of gold fell and the trade deficit fell. You’ll notice the same thing has been happening since the price of gold peaked about a year ago.

Inflation abroad is causing the same scenario to play out. Foreign central banks are slowing reserve accumulation, which leads to more dollars returning via US exports (as opposed to financial asset accumulation) and higher foreign currencies, which leads to higher corporate earnings for US companies and higher interest rates, which leads to lower consumption growth and slower import growth, which leads to a lower trade deficit. As the imbalances subside, the economy is put on a more sustainable growth path.

What could make the adjustment fast instead of gradual? 1. Protectionism in the US, which would lead to a spike in interest rates (under consideration by the current congress). 2. Higher taxes (happened in the late 1980s, even as the deficit was falling…could happen after 2008, even though the governement deficit is less than 2% of GDP and falling). 3. Sudden changes in the pattern of government spending (reduced military spending in late 1980s and early 1990s slammed places like southern CA). 4. Sudden changes in financial markets regulation (S&L regulations in late 1980s, tightening of subprime criteria today). 5. Good-old-fashioned financial markets excess that just HAS to come to an end (always a threat).

If our leaders let calm heads prevail, the outcome doesn’t need to lead to disaster.

Different subject, but please pass to Professor Hamilton that, based on today’s terrible retail sales data, he was premature, last week, to call his move, two weeks ago, to ‘frown’ premature.

He was right to move to ‘frown’ two weeks ago.

It is going to be ugly, in the real economy and soon thereafter, the stock market, these next few-to-six months.

There are some good comments upthread about how the Asian currencies are really the problem. By remaining artificially low, they squeeze Europe.

Now, they have good reasons to keep their currencies low. Especially in China, employment is critical for social stability. The flip side is that low currencies keep living standards low.

India has done a small re-valuation and China has also committed to a (smaller) re-valuation, both probably to diminish inflation. But a virtuous circle could begin: as countries strengthen their currencies, other countries will feel encouraged to follow. The rise in living standards will offset the slowing of employment growth (and encourage internal growth; China in particular needs infrastructure).

That would leave the dollar/yen ratio like the proverbial nail sticking up.

I’m wonderwing what happens when the U.S. stock market has its long-overdue correction, especially if the Fed hasn’t raised rates in the meantime. The drop in the dollar means that despite a 25% increase in the S & P in the last 2 years, a European would only see about a 10% total return, due to dollar depreciation. Combine that with headline inflation running at 4-5 percent, and that’s barely a real return.

Sonner or later, you have to think those Euorpean and Asian investors are going to turn more and more to the DAX, Chinese and London markets, especially if the U.S. markets has a “correction”. I’m frankly surprised more of this hasn’t happened already, given that Asian and European GDP growth is surpassing U.S. growth, and should continue to do so for a while.

One little trigger, and it’s a whole mess of cards that can fall. Bush and co. is just hoping it doesn’t happen in the next 18 months so it can be blamed on whoever takes over this tenuous situation.

Menzie wrote:

DickF: Sorry, I must be missing something. How can all currencies by depreciating? In any event, the trade weighted dollar is depreciating in both nominal and real terms, against both a broad and narrow basket of currencies (the nominal, narrow index is shown in Figure 3).

Menzie,

I am surprised but, yes, you are missing something.

Do you know the word “numeraire?” For those who may not be familiar with the word here is the Econoterms definition.

Definition: The numeraire is the money unit of measure within an abstract macroeconomic model in which there is no actual money or currency. A standard use is to define one unit of some kind of goods output as the money unit of measure for wages.

If you define the appreciation or depreciation of a currency only against other currencies you know nothing about world numeraire appreciation or depreciation.

Let me use a relativity illustration. There are two trains traveling from Boston to New York: train one traveling 60 MPH and train two at 50 MPH. Would you say that train one is only going 10 MPH? You would if your anchor of reference is train one. Additionally you would say that New York is traveling toward you at 50 MPH.

But what would you say if your anchor was train two. It appears that train two is traveling away from New York at 10 MPH while New York is traveling toward you at 60 MPH.

But to have a true frame of reference relative to your origin and destination, Boston and New York, you need to use one of them as your reference point. So from Boston one train is going 50 MPH and the other is 60 MPH.

If your definition of appreciation/depreciation is currency against currency then you get a relative answer, but if you consider the currency movement against the world numeraire – is there actual inflation or deflation of each currency – you get a true answer of the purchasing power of the currency.

If you ignore the currency movement against the numeraire you only get part of your answer and it can be seriously misleading. For example in the Great Depression all currencies worldwide were deflating but the monetary authorities couldn’t see it. Their policies exacerbated the deflation. In such an environment today looking at relative FX might lead to the same deflationary policy if one currency was depreciating against other currencies but appreciating against the numeraire. Just another reason that gold is so important in evaluating FX – gold is the best proxy for the numeraire.

Jake Miller wrote:

The drop in the dollar means that despite a 25% increase in the S & P in the last 2 years, a European would only see about a 10% total return, due to dollar depreciation. Combine that with headline inflation running at 4-5 percent, and that’s barely a real return.

Jake,

Don’t get caught. Your reference to “dollar depreciation” against European currencies contains what you call “headline inflation.” See my post to Menzie above.

David Pearson wrote:

In Argentina, an antarctic blast of cold air is forcing the government to choose between price controls and heating homes. If it loosens price controls, inflation will “un-anchor”. Or it could revalue, in which case the rise in energy prices will be cushioned by a dollar devaluation.

David,

Do you not understand that price control in Argentina is the cause of energy shortages? Revaluation of the currency will not bring more energy on line. The people are not freezing because of the number of dollars in their pockets unless you believe the dollars can be used to plug holes in the walls of their homes to keep out the freezing winds. The people are freezing because of a shortage in energy caused by driving producers out of the market with price controls. I refer you to Thomas Sowell on big city rent controls.

DickF: Thank you explaining to me a numeraire. However, your definition of depreciation is not standard in the international finance literature, and indeed not standard in modern macroeconomics.

You are free to define the numeraire to be anything you want, but it would seem to me that gold is not a terribly useful one. Indeed, that is why I use (implicitly) the numeraire I do — a bundle of home goods (the graphs are of nominal rates, but for US and euro area or USD against major currencies, the inflation rates are similar enough that the real and nominal rates are similar). See this survey for the New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, and this primer about real rates, relative prices, and numeraire.

For your interpretation to be correct, I think you’d be looking at a world price level, and assuming abslute purchasing power parity (something we know doesn’t hold even in the long run).

Menzie wrote:

For your interpretation to be correct, I think you’d be looking at a world price level, and assuming abslute purchasing power parity (something we know doesn’t hold even in the long run).

Menzie,

I actually believe it is just the opposite. If you believe that FX is independent of a world numeraire then you are assuming an absolute purchasing power parity that does not exist. Purchasing power of various currencies are relative to other currencies in foreign trade but a monetary authority that ignores the purchasing power fo its currency for domestic goods would be foolish indeed.

By far the most important measure of a currency is its purchasing power relative to domestic goods and if this domestic purchasing power becomes subordinate to FX then power is ceded to foreign central banks. The Argentine and Brazilian monetary authorities in the 1970s can speak to this directly as US monetary policy virtually destroyed their economies.

Menzie,

This is not criticism but a serious question. I did not find the numeraire mentioned in either of your papers that you referrenced, I did a word search. I assume that you use the “basket of goods” definition.

In the economic literature there are differences of opinion as to the meaning. Much of the literature does define the numeraire as a basket of goods, but I find this unsatisfactory because it introduces potential error from the imaginary value of all goods in an economy because it is impossible to determine the basket without complete knowledge of every change at every moment in an economy. To be meaningful the numberaire must be imaginary.