The latest economic data have surely warranted a downward revision in the Federal Reserve’s assessment of near-term economic performance. It therefore might be a good time to review the steps the Fed could take if it wishes to provide further economic stimulus.

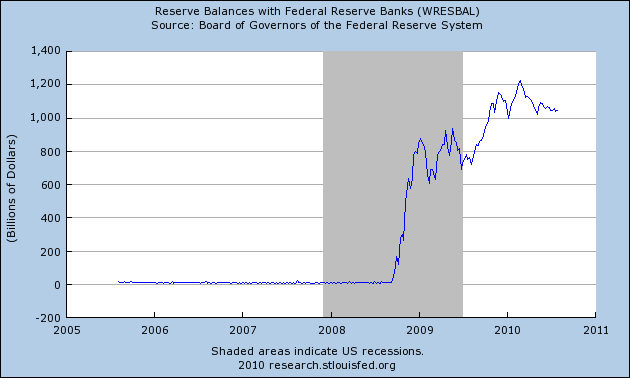

One option that has been discussed is lowering or eliminating the interest that the Fed pays on deposits that banks maintain in their accounts with the Fed. These accounts typically amounted to about $10 billion in normal times, but have grown to over a trillion dollars since the Fed began paying interest on reserves in the fall of 2008.

|

But Dave Altig isn’t persuaded that eliminating interest on reserves would make much difference. He notes that the gap between what banks can earn by leaving the funds idle in their accounts with the Fed at the end of the day (0.25%) and a used car loan (about 8%) is so large that increasing it another 25 basis points by eliminating the payment of interest on reserves really wouldn’t make much difference for banks’ incentives to make this kind of loan. Instead, Dave endorses the conclusion of Barclays Capital’s Joseph Abate:

If banks didn’t get interest from the Fed they would shift those funds into short-term, low-risk markets such as the repo, Treasury bill and agency discount note markets, where the funds are readily accessible in case of need. Put another way, Abate doesn’t see this money getting tied up in bank loans or the other activities that would help increase credit, in turn boosting overall economic momentum.

But Dave doesn’t quite finish the story. If I as an individual bank decide that a repo or T-bill looks better than zero, and use my excess reserves to buy one of these instruments, I simply instruct the Fed to transfer my deposits to the bank of whoever sold it to me. But now, if that bank does nothing, it would be left with those reserve balances at the end of the day on which it earns nothing, whereas it, too, could instead get some interest by going with repos or T-bills. The reserves never get “shifted into short-term, low-risk markets”– instead, by definition, they are always sitting there, at the end of the day, on the balance sheet of some bank somewhere in the system.

The implicit bottom line in the Abate story is that the yields on repos and T-bills adjust until they, too, look essentially to be zero, so that banks in fact don’t care whether they leave a trillion dollars earning no interest every day.

The essence of this world view is that there are two completely distinct categories of assets– cash-type assets which pay no interest whatever, and risky investments like car loans that banks don’t want to make no matter how much cash they hold.

But I really have trouble thinking in terms of such a two-asset world. I instead see a continuum of assets out there. As a bank, I could keep my funds overnight with the Fed, I could lend them in an overnight repo, I could buy a 1-week Treasury, a 3-month Treasury, a 10-year Treasury, or whatever. Wherever you want to draw a line between available assets and claim those on the left are “cash” and those on the right are “risky”, I’m quite convinced I could give you an example of an asset that is an arbitrarily small epsilon to the right or the left of your line. Viewed this way, I have a hard time understanding how pushing a trillion dollars at the shortest end of the continuum by 25 basis points would have no consequences whatever for the yield on any other assets.

The way to do the same thing in a bigger way is of course to raise the implicit penalty on idle cash through inflation. Whenever I make this point, some readers respond that I am proposing to turn America into Zimbabwe or steal the earning power of honest workers. If I as a modest blogger face such reactions, I can understand the difficult public-relations tightrope act faced by the U.S. Federal Reserve. Notwithstanding, it is very clear to me that deflation can be quite harmful, and that particularly given our present circumstances, moderate inflation rather than deflation would produce a clearly superior real outcome for essentially all Americans of every walk of life. But how exactly can the Fed prevent deflation?

In addition to the proposals I outlined a few weeks ago, Arnold Kling adds the suggestion that the Fed could buy more foreign assets:

If the Fed announced a policy of “20 percent weaker dollar or bust,” and proceeded to buy euros, yen, and other currencies, by golly, I do not think that private speculators would try to get in the way. And if foreign governments tried to get in the way, that would probably lead to some sort of worldwide monetary expansion that I imagine would make [Scott] Sumner happy.

A weaker dollar would of course not only prevent deflation, but would also help discourage U.S. imports, which I see as both a near-term drain on domestic aggregate demand as well as a profound long-run challenge.

But let me close with the same caution I offered when discussing this issue two weeks ago. There are limits to what we can expect monetary stimulus to accomplish, and the speed-limit sign I recommend that the Fed should observe comes from watching what happens to commodity prices. If a strategy of dollar depreciation begins to show up in significant moves in relative prices, I think that’s an indication the policy has accomplished all that it could.

It’s a mistake to ask too much of monetary policy. But preventing deflation is definitely something we should ask the Fed to do, and well within the Fed’s power to achieve.

Scott Sumner has convinced me that nominal GDP targeting is the way to go (though I’m skeptical of his proposal to do so at a 1-year horizon using futures market as an absolute guide). What you want to do is create inflation expectations in the intermediate run but not in the long run. (Ideally we want to create inflation expectations in the short run, but I doubt that’s possible.) If we set up nominal GDP level targets based on the pre-recession trend, they would imply high inflation until we start hitting the targets and then low inflation thereafter. That is exactly what need.

And nominal GDP targets are a gift that keeps on giving. Next time we have a severe recession, if we have nominal GDP targets, we won’t have to worry about a liquidity trap, because the recession itself (since it, more or less by definition, reduces the real component of nominal GDP, presumably without raising the inflation component) will automatically increase the inflation target, thereby reducing the real interest rate. It’s the monetary equivalent of an automatic stabilizer.

JDH: First rate post. There’s a lot of room between moderate inflation and Zimbabwe.

Do you have a specific commodity index in mind that we should watch, or is that a new research project for someone? Is there a core index that would capture general price inertia and would filter out volatile commodities? What if crude commodity indices point in one direction, intermediate commodities point in another direction and finished commodities point in a third direction?

Proponents of moderate inflation make a key assumption: the Fed will not have to tighten until the output gap is eliminated. Imagine, instead, that headline inflation hits 4% while unemployment is till over 8%, and the Fed is faced with a choice between fighting inflation and extending the slump. I think the critical question is the inflation/deflation debates is, “how likely is this scenario?” Presumably, Scott Sumner and Paul Krugman would agree that it is highly unlikely. You, on the other hand, at least imply that commodity prices might spike even under a large output gap.

Could the Fed tighten with unemployment over 8% and the %>26wks skyrocketing? This is a political question, not an economic one. I think most would agree that the answer is, “no”. Note the “tightening” doesn’t mean raising interest rates or selling assets; it can mean just stopping asset purchases before the market expects.

Price level targeting rather than inflation targeting is the way to go, but as bankers like to fail conventionally than succeed unconventionally, is this too much to expect?

If we desire a weaker currency and can act to create it, why can’t every other country?

It seems that would very likely be a zero sum game.

I believe the Fed can do enough to keep significant deflation at bay, but I’m not sure they’ll be able to create significant inflation while lending is still falling at about a 5% annual rate.

Japan opened the monetary spigot and at the same time manipulated their currency, but it didn’t get them inflation.

The Economist discussed the FX option recently.

The Economist thought Bernanke wouldn’t take the political risk of printing money to flood the FX markets. I think if the data stays ugly, he will.

This would be likely to trigger a global game of competitive devaluation, though. I’d buy gold if it looks like that’s the game plan.

Is there anything preventing the Fed from charging a negative interest rate on reserves?

I’m persuade by Prof. Hamilton. The Fed should folow his advice. I see little or no downside risk. If it does not increase lending, it will at least aid the Fed balance sheet.

However, trying to use the financial spigot as a level is not the best initial strategy, today. Reducing the trade deficit is the best strategy today.

David Pearson: Imagine, instead, that headline inflation hits 4% while unemployment is till over 8%, and the Fed is faced with a choice between fighting inflation and extending the slump.

The situation you lay out is a case of trying to use one policy lever to manage two problems. This could happen if the new NAIRU settles in at 6%-8% due to a higher level of structural unemployment, and the best way to guarantee that kind of bad outcome is to fight the recession with one hand tied behind our backs. That’s why we need fiscal stimulus alongside monetary policy. Get people back to work so that they don’t lose both their skills and the discipline of the workplace.

What’s wrong with changing relative prices, anyhow? Who is to say that the current levels of relative prices are efficient? In a world where labor supplies are rising and natural resources are limited, relative prices of natural resources should be rising. Who is to say that they have already risen enough (which would imply that they rose way too much a couple of years ago)? Maybe the 2008 peak was efficient. If I had to guess, I’d say that even commodity prices at the 2008 peak were below the efficient level. Even before the fall, there was a liquidity crisis in 2008 that was artificially restricting demand for commodities. If anything, the Fed should target them to rise above mid-2008 levels.

Why do people say changing (lowering or eliminating), the interest rate paid on excess reserves, won’t help encourage the banks to lend or invest? If that is so, then why do the taxpayers pay the banks to hold excess reserves in the first place?

IORs are a credit control device. IORs are the functional equivalent of required reserves. The banks aren’t deciding whether to lend or invest, the BOG is.

From the standpoint of the entire economy legal reserves were never a tax. An increase in excess reserves allowed the commercial banking system to acquire a multiple volume of new earning assets (as well as the Treasury to recapture some interest).

The irrational point of bank deregulation was to undercut the Euro-dollar market’s low expense ratios.

Also, nominal gDp can’t be targeted because the lag for nominal gDp varies widely. However, the lag for inflation is fixed. Obviously, the only achievable mandate is stable inflation.

To assume that the Federal Reserve can solve our unemployment problem is to assume the problem is so simple that its solution requires only that the Manager of the Open Market Account buy a sufficient quantity of U.S. oblgations for the accounts of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks. That is utter naivete.

The idea that unemployment can be reduced to “tolerable levels” simply by pumping up aggregate demand is both naive and dangerous.

But the majority of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) will act (QE2) in the 4th qtr, on the assumption that monetary policy can play a major role in solving the problem of chronic unemployment.

Andy Harless:

I agree, but that means extreme hardship for the working class and middle class.

Try feeding a family of four with skyrocketing gas and food prices and wages up only marginally if you’re lucky enough to have a job at all.

Andy Harless: “If I had to guess, I’d say that even commodity prices at the 2008 peak were below the efficient level.”

That sounds kind of silly to me. Personally, I think commodity prices were clearly inflated by speculators and I think we just had a second mini-bubble.

Most commodity prices have been falling in real terms for one hundred years. When we do have commodity driven inflation, it’s usually been just before a recession.

It’s interesting how there seems to be little argument about whether inducing inflation is a good idea, just about whether it can be done or not.

Am I the only one here who owns any fixed-rate bonds? No one with a pension fund that will suffer? Does everyone think they’ve hedged for inflation?

Bob_in_MA,

From what I’ve seen, the evidence does not support the view that commodity prices were inflated by speculators in 2008. If so, you would have expected to see unusually high levels of inventories — either inventories owned by the speculators themselves or by arbitrageurs seeking to profit from the difference between cash and futures prices. Inventory levels were not particularly high in 2008. But even if it had been speculation, that wouldn’t mean it wasn’t efficient. Rational speculators will hoard commodities when they are underpriced relative to the fundamental. And if commodity prices have been falling in real terms for one hundred years, that’s all the more reason to think they might be underpriced today.

I’m not necessarily saying that commodities are underpriced. I’m just saying that rising commodity prices should not be taken as a sign that Fed policy has gone too far. What reason is there to presume that today’s prices are efficient?

Regarding fixed rate bonds, I own them too, based on my expectation of what the Fed will do, not my belief about what it should do. If you’re worried that the Fed will follow a more inflationary policy, then go ahead and sell your bonds. That’s sort of the point. If the Fed can raise inflation expectations, then people will be forced to invest in things that are more productive than pieces of paper.

If exporting our unemployment through dollar depreciation is our best strategy for monetary loosening, we are truly sunk. Think about what would happen to Europe, with Chimerica trying to lever its massive bulk on their slender back. Anyway, isn’t currency intervention done under the authority of Treasury?

Much better – make meaningful threats against foreign currency interventions, and back them up with meaningful actions.

Furthermore, recall what massive intervention did for Japan in their malaise – despite a smaller and more open economy, and a healthy ROW, it was not enough to prevent local deflation.

(The yen is still undervalued – they never completely abandoned their export-led growth strategy.

Jim, regarding the IOR, why couldn’t the Fed use a two tier rate:

High on required reserves

Low, zero or negative on excess reserves

The idea is to incent them to increase loans by paying more on the reserves required to back them. Perhaps do it only on new loans, so a three tier rate. One way to view this is as offsetting some portion of the current risk premium banks require.

And do it until excess reserves are at a much lower level.

And do so until

I guess there is no interest in having a market generated interest rate. You know, one that emerges from the interplay of the supply of savings & the demand for loans rather than the manipulation of gov’t bureacrats.

There was a time when economists understood that market prices were essential to optimal allocation of resouces.

“The way to do the same thing in a bigger way is of course to raise the implicit penalty on idle cash through inflation.”

Bingo!

It used to be that interest on debt servicing was revolving around 5% of revenues or total income for a manufacturing company (at a higher nominal interest rate than now).

Should they at present be higher, it will be only because of leverage,that can be solved through shares prices or bond prices (assets prices is a component, assets prices are an issue).

Banks used to operate under a mantra, security,liquidity,profitability. When asked to dance a different partition they have foregone liquidity, pumped up prices and wrote off the real profits (assets prices were and are the issue,liquidity the catalyst).

When consumers were asked to consume they consumed in credit 125 % of the US GDP and 100 % of the European GDP (liquidity trap)

Is monetary policy the only topic?

According to the German “BLS” we have almost no inflation in Germany ( ca. 1.2% )but my personal expenses are growing much faster. In a corner of the BLS web site I found something which they call harmonized CPI which apparently is CPI measured the European way and in this table US annual CPI in Q1 was 3.6% :

ftp://ftp.bls.gov/pub/special.request/ForeignLabor/flshicp.txt I have to wonder whether this “deflation threat” is just another Red Herring spread by the Fed to manipulate the publics perception of inflation in terms of living expenses and thus being able to start QE2 without lifting inflation expectations.

As I said in Scoot Sumner blog, I think the last NGDP data reduce the deflationay risk. NGDP has risen 4% (same Q a year ago) face to 2,8% in the first Q. The NGDP is growing up, as can be seen in

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_UlqNAo7QxaA/TFXH-gqLNPI/AAAAAAAABPI/UplZb1O7okM/s1600/difz.gif

That is confirmed by the good performance of non residential investment (as you point out few days ago), a sign of optimism in Corporate sector.

I dont see so high defaltionary risk.

Its not intuitively obvious that the Fed ever has “an interest in having a market generated interest rate.” Simply not their statutory obligation, which is stable prices and minimum unemployment.

And it is not intuitively obvious that 10% or so unemployment, and 74% or so capacity utilization is “optimal allocation of resources.”

Surely, Bryce, you are not arguing that the current unemployment rate demonstrates the Fed is meeting its statutory obligation. Or are arguing that the current state defines an optimal allocation of resources. Are you?

It would be far more useful to the 15 or 16 million officially unemployed who are more worried about eating than efficient resource allocation to talk about what the responsible fiscal and monetary officials can do to improve the state of the whole economy rather than defend the canard that economists can have no sense of social morality and equity, and thus should not use available tools to advance those causes.

I’ll try to save those who are outraged the trouble by anticipating your reply: “if “they” stop “meddling” then the “efficient markets” will “take care” of everything.”

JDH: You needed to follow through further with your thinking on what happens if the Fed were to reduce or eliminate the interest on reserves.

You’re right that there is no macroeconomic importance to exchanges of reserves for other low-risk assets as long as the volumes of reserves doesn’t shrink and the volume of other low-risk assets doesn’t grow. That is what is happening now – such exchanges are going on all the time, but the interest paid on reserves is at the right level to keep the volume of reserves stable.

If the interest rate paid on reserves were lowered, there would be increased incentive for all banks to reduce excess reserves. Thus they would engage in numerous transactions that would increase the total volumes of credit, broad money and currency in circulation, while reducing excess reserves. The growth in currency would be one for one, the growth in total system credit and broad money would be several times greater. If interest on reserves were eliminated, which I certainly don’t expect, excess reserves would head to zero, doubling currency in circulation and massively expanding credit and broad money. It is a long way from moderate inflation to Zimbabwe, but eliminating interest on reserves without first draining the $1 trillion of excess reserves would take us most of the way there, rather quicker than you might imagine.

You do touch on an important conundrum: when money supply is rapidly expanding, the supply of low-risk assets can’t feasibly be increased quickly enough to meet growing demand. Markets tend to solve this conundrum by producing pseudo-low-risk assets and creating asset bubbles.

There seems to be some misunderstanding about excess reserves. Banks have little control over the aggregate level of reserves in the banking system. They can obviously reduce the level of reserves they individually hold, but this simply forces the reserves to another bank. Reserves in the banking system are a function of the FED’s balance sheet. IOR simply creates a floor under overnight rates. Without IOR, overnight rates would go to zero because there are excess reserves in the system.

Fullcarry: The Fed can increase or decrease reserves by buying or selling assets. Commercial banks can increase or decrease reserves by converting currency into reserves or vice versa. In practice, the conversion of reserves into currency by commercial banks occurs through expansion of credit and broad money.

Tom: “The Fed can increase or decrease reserves by buying or selling assets.”

That is correct.

“Commercial banks can increase or decrease reserves by converting currency into reserves or vice versa.”

Currency holdings of commercial banks (vault cash) is considered reserves. It is only when depositors convert their deposits at a bank into currency that reserves are reduced.

“In practice, the conversion of reserves into currency by commercial banks occurs through expansion of credit and broad money.”

Credit expansion does increase required reserves. But required reserves are a small fraction of the aggregate reserves in the system (they total 60-70B right now).

Banks aren’t constrained by reserves. They are constrained by their capital, their risk profile and qualified borrowers.

Car loans are NOT 8%. I just got a USED car loan, on an 8 year old vehicle no less, for 3% on a 60 month term (from a credit union, not a bank).

That puts the 0.25% in perspective, doesn’t it?

Interest on reserves is all about rebuilding bank ballance sheets. The Fed, no mattter what it’s “mandate” is, is all about doing what is best for the banks that it serves.

Anonymous: You’re right that it is the clients of banks who directly cause the conversion of reserves into currency, by withdrawing currency from their bank accounts. But it is the commercial banks who indirectly cause such conversion by increasing credit and broad money, which increases the demand for currency in the economy.

Yes, as commercial banks increase credit and broad money, their reserve requirements increase. So if interest on reserves were eliminated, we could expect roughly 90 percent of excess reserves to be converted into currency and the rest to become required reserves.

No individual bank is constrained by its individual reserves, but the banking system as a whole is constrained by the overall availability of reserves, which determines the cost of interbank lending. The Fed guides interbank lending rates to its target rate by manipulating the availability of reserves.

I should stress though that the complete elimination of interest on reserves, without first draining the large excess reserves, is a radical scenario, which no one expects to happen. It’s not really important to be able to predict exactly what would happen in a radical hypothetical scenario. Havoc. Enough said.

What I sense people here are having trouble getting their heads around is how reserves differ from other kinds of cash. Here we’re interested only in excess reserves held at the Fed, not in required reserves or vault cash, which aren’t big variables.

Currently, excess reserves held at the Fed pay a small interest, 0.25%/yr, which is enough to make them preferable to their closest alternative, which is overnight interbank lending, which currently pays only about 0.18%/yr, and has greater, albeit still very small, counter-party risk.

From the individual commercial bank’s standpoint, these are just two different kinds of cash. But from the macroeconomic standpoint, cash held as reserves at the Fed is much more sterile, because the Fed does nothing with it, whereas cash lent overnight to a commercial bank will be utilized in the economy, and generally re-utilized several times over. The difference is very similar to that between personal cash held as currency stuffed in a mattress, which is effectively withdrawn from circulation, and personal cash on deposit in a bank, which will be lent on, re-deposited, lent on again, etc.

Professor,

The real problem is the definition of “deflation.” If deflation is a monetary event then an increase in the supply of money can ease the deflation, but if deflation is actually not monetary but a contraction then pumping in more money will not solve the problem and will probably make it worse by threatening stagflation.

Too often deflation is recognized as a decline in prices, but that is actually not a definition of deflation. A decline in prices could be from an appreciation of the monetary unit, but it can also be from a decline in business activity, from a decline in demand. This is usually due to uncertainty where investors sit on their capital rather than risk it.

Uncertainty is primarily due to a fickle government meaning the investor cannot rely on the consistency of the government nor the rule of law.

It seems clear that our current decline is not from monetary deflation but is primarily due to uncertainty meaning that it cannot be reversed by monetary pumping. As a matter of fact monetary pumping actually makes the situation worse as the uncertainty of the value of the monetary unit adds cost because investors have to arbitrage windfall losses due to currency fluctuations. This also leads to greater uncertainty of investors because of the instability of the monetary unit (think the euro).

Monetary pumping, to create inflation during a contraction, is very dangerous because money tends to pile up during a contraction; it sits unused because of the uncertainty. Once the money supply becomes so large that it actually begins to generate inflation the decline in the value of the monetary unit feeds on itself and chronic or even hyper inflation can result. If the monetary authorities attempt to moderate the inflation then real deflation can kick in and we have the worst of all worlds. A contraction driven down by actual monetary deflation. Then we will be looking in the face of the Great Depression.

The volume of interbank demand deposits held at the District Reserve Banks, owned by the member banks reached the all-time high (as a percentage of note and deposit liabilities) @ 91.1% in 1941.

Inspite of $1.035T in excess reserves, the weighted arithmetic ratio is infintessibly smaller today @ $1,045T/$9,235T.

Regardless of the extraction route, e.g., IORs, reserve ratios, reservable classifications, etc., any increase in the outstanding volume of IBDDs is, other things being equal, contractionary.

I.e., the BOG used the remuneration rate on IORs to offset the expansion on the asset side of the FED’s balance sheet (i.e., the huge increase in Federal Reserve Bank Credit).

It is the outstanding volume of IBDDs that reflects the degree of restraint or slack inherent in the FED’s open market policy. I.e., a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.

Steve Bannister,

We got here to 10% unemployment because of the misleading non-market interest rates set by the central banks of the world.

We have fiat money only because market-produced money is uniformly suppressed by gov’ts. This would not be the case in a free world or a free market. All we need is for one gov’t to allow it.

Cheers to what Ricardo said.

I’m reminded of the debate over the Fed’s policies during the Great Depression, when interest rates were very low despite money supply contraction caused by hoarding of currency and conversion to gold. The Fed did little to counteract the contraction as board members argued that increasing money supply couldn’t lower interest rates significantly and therefore wouldn’t be effective. Most modern economists, especially Keynesians, point to the Fed’s reluctance to counteract money supply contraction as one of the big policy mistakes exacerbating the depression.

Personally, I think that after the much bigger mistakes of not dropping the gold standard and not countering the waves of bank runs, the Fed really didn’t have much power to help matters anymore.

Certainly increasing money supply always has effects, and would have had in the 30s just as it would now. But not necessarily positive effects. I see nothing to be gained and much to be lost from increasing money supply in current conditions.

Sumner responds specifically to Altig/Abate.

“This is one of those situations where I dont know whether I should be criticizing Abate, for what he said, or Altig, for seeming to approve of it.

“But whoever is to blame, this quotation seems to get things exactly backward, and does so by focusing on credit, rather than money… ”

Three thoughts. First, a personal note.

Our administration has said that wages are going to be frozen until 2013 at least. If I was sure that prices were going to rise while my income was frozen, my response would be the same as if prices were held steady and my wages cut: reduce spending and increase savings.

Highly stimulative.

Of course, a logical answer would be “Well, bad luck for you, but economic policy needs to serve the country as a whole.” So my second comment is a thought experiment.

Suppose that the Fed decided to buy large quantities of junk bonds. What happens?

Junk bond holders make money. Companies with junk ratings get access to the bond market more cheaply. This might stimulate business activity if there are many credit starved firms falling over themselves to invest when they get the money. Otherwise it might just fund stock buybacks.

Meanwhile, returns on junk bonds are lower (which probably has some effect on the value of the dollar) and the money managers who sold their junk bonds to the Fed are looking for yield. According to Bloomberg, at least, on the days when money managers get adventurous they put money into stocks, especially emerging market stocks, and commodities. So a small percentage of stockholders earn capital gains and the majority experience price inflation.

My guess is that the negative effects outweigh the positive ones.

Finally, the overall wage trend of the past decade has been for the top one percent to profit wildly, the rest of the top quintile to do fairly well, and everyone else to stagnate. Why would inflation change this trend?

Anyone notices the oil price? More than $80 now. The problem of trying too hard to keep interest rates low for too long is that low rates boost energy prices, which acts as a negative shock to US growth … this is how stagflation is made.

“It’s interesting how there seems to be little argument about whether inducing inflation is a good idea, just about whether it can be done or not.”

Indeed amazing. “We Need Inflation” sounds like parrotspeak straight out of some ivory tower economics school textbook.

Absolutely bizzarre that folks don’t remember what precipitated the crisis in the first place: spike in prices starting with Oil, sending household budgets haywire, and ARM resets finishing the job.

http://tiny.cc/Deflationomics

Also, Great Q: “No one with a pension fund that will suffer? Does everyone think they’ve hedged for inflation?”

Good post.

Let’s also not forget that the discount rate is at .75 and so could be cut, that the federal funds rate could still be cut to zero, and that QE could be used to reduce any of the other longer-term securities yields…

There are just a multitude of things the Fed could do if it wanted to hit its inflation target…

Agree with Andy Harless above on oil prices, but note that speculation can also take the form of keeping oil in the gound.

Have any of you ever thought about the IMMORALITY of the Federal Reserve’s actions? Stealing income from some of the most vulnerable members of society (seniors, pensioners, charitable endowments, and others who depend on income) for some dubious benefit to the “system” is obscene. Deliberately forcing interest rates lower STEALS and redistributes income. Grandma can’t heat her house this winter because her life savings now pays just 0.25%, but all the McMansion owners can refinance at even lower rates and purchase a new prius with 2% APR financing. There must be a natural balance between savings and consumption in society. The Fed has us on the road to destruction, full speed ahead.