I earlier

attempted to explain some basic economic perspectives on oil depletion to those who usually

think about the issue from the vantage point of other disciplines. Now I’d like to attempt the

no less perilous task of carrying water the other way across the street, describing to

economists who may find themselves skeptical of the claims made about “peak oil” what I regard

to be some useful insights from geologists and engineers to which some of us have perhaps paid

insufficient attention. As a skeptic and an economist myself, perhaps I’m qualified for that

mission.

|

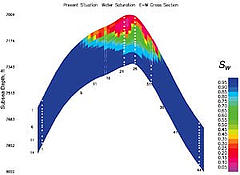

The figure at the right displays relative fluid densities at different depths for a vertical

cross section from the Abqaiq oil field in Saudi Arabia. The Oil Drum

explains what it means:

Over time the field has been injected with water (the blue zone) and this has pushed up the oil

(the green zone) into the wells. The red is the overlying gas cap. When the reservoir was

untapped it was likely all red and green. After all these years of pumping you can see how

little of the green– the oil– remains. The field is about 800 ft thick from top to bottom and

about 1.5 miles below the surface.

There are methods for trying to get as much of the remaining oil out as possible, and indeed,

the article from which this figure was

taken describes one such strategy. However, once development reaches a certain point, the

production flow rate from the field has to decrease. If one wants to keep on taking a larger

quantity of oil out of the ground each year, the only way to do that is to keep finding new

reservoirs.

|

The graph at the left displays annual U.S. crude oil production since 1949. This peaked in

1970 and has been declining pretty steadily since, standing currently at a lower value than any

point during the last half century. It’s clear that this decline was not caused by

displacement of U.S. production by cheaper imports. Exactly the opposite is true– the cost of

imported oil shot way up in 1973 when U.S. production declines first set in and the U.S. was

forced to become a bigger buyer on the world market, just as the most recent U.S. production

declines surely contributed to the rising price of world oil over the last several years.

Admittedly, one can never rule out the possibility that advancing technology or significantly

higher prices than we’ve seen so far might bring U.S. production, at least for a while, back up.

Still, a 30-year record of declining production, despite the technological and price advances

that we’ve seen over this period, should raise in anyone’s mind the strong suspicion that, no matter

how strong the incentives, U.S. oil production will never return to the values last seen in 1970

when oil sold for $3 a barrel.

And a rational person would certainly have to allow for the possibility that the same thing

that happened in the United States sooner or later is going to occur on a global basis. I

personally am not inclined to dismiss the claims of those who say it is going to be sooner

rather than later, but investigating that issue gets into some subtleties and controversies that

I’d prefer to avoid at the present time. Instead, my purpose here is to call attention to a

fact with which I believe even the most hardened skeptic of peak oil would want to agree.

Specifically, I propose that we should all agree that the answer to the question, “why doesn’t

the U.S. just stop importing so much oil?” is, “because we can’t.” We can’t, and not because we

were never endowed with oil resources in the first place– the U.S. produced significantly more oil over

this half century than did Saudi Arabia. Rather, we can’t because we burned what we had, and,

if we want to keep on doing things as we’ve been, we now need to obtain more oil from somewhere

else.

I also think it should now be clear to everyone that getting that oil from somewhere else is

not without its own significant costs. Included in these are not just the dollar flows associated with oil imports, which

to be sure are staggering. In

addition, the Middle East is a place of substantial turmoil, and the next major supply

disruption from that region is not a question of if but when. I am among those who believe that

the economic costs of such disruptions can be quite considerable. Furthermore, the extent to

which those oil revenues have been used to promote forces quite hostile to American

interests may be difficult to quantify, but that does not make it any less of a potential

concern.

I then find myself asking the question, suppose we did conclude that the importation of oil

was an unacceptable option. What would the alternative be, and how would we get there? I fear

that the responsible answer to that question is, the task is almost overwhelmingly daunting.

Once you look at the details of any particular plan, you will probably end up concluding that,

no matter what the cost of oil imports, we are better off just paying that cost and relying ever

increasingly on imported oil.

And that in turn leads me back to the question, what happens when we experience on a global

scale the same depletion that’s occurred in the United States, so that we have no alternative at

all other than this Plan B? Yes, I know, that’s the “sooner or later” issue that I promised not

to bother you with the details of just yet. But it’s a question that seems well worth

pondering.

Those are good points but I have several comments.

First, I don’t see that your message is particularly aimed at economists. It seems to be a more general summary of some of the facts relating to the Peak Oil scenario and doesn’t particularly speak to economic questions like responses to incentives (except the one point regarding the U.S. response to the oil price increases in the 1970s, which I will discuss below). Economists will continue to ask the same questions you raised, basically what is that $100 bill still doing on the sidewalk even after all these people have walked by (i.e. if it’s so obvious why are the markets not responding to get rich).

Also, with regard to the Abqaiq oil field, the article you link to says that since it began production in 1946, “more than 50%” of the oil initially in place has been produced. The chart would seem to show much more than 50% gone. Visually it looks more like 80% extracted. So I think the chart is a little misleading. It may be that there is still oil mixed with the blue water area, which could be recovered with future technology, or it may be that this particular part of the field is drained more than others due to the nice “cap” formation which has led to a number of wells being put right at the top.

As far as U.S. production, it appears that once oil prices shot up in 1973, U.S. production actually increased from 1975 to 1985. Since then it has declined steadily. The interesting factor will be whether we begin to see an increase again. You’re right that it is very unlikely that we will get back as high as 1973, but still if we can begin to increase production then that could make a significant difference. A successful U.S. production increase would also mean that other parts of the world can do so as well, even areas that are also in decline. This is an important question which will affect the near term course of the oil shortage. The fact that a price increase turned a production decline into a production increase could be an important clue to what to expect.

Frankly I don’t see what is so bad with “getting oil from somewhere else.” That’s what we call trade, and it is what has made the world as wealthy as it is. We get lots of stuff from somewhere else. I’ll bet if you looked hard enough you could find some other commodity that we get from somewhere else and which we couldn’t easily replace if it got cut off. Yes, oil is special, but the problem isn’t really that we’re getting it from somewhere else, it’s that we’re running out of it. Even if every country were equally self-sufficient with oil, if we all faced running out of it in a few years, we’d still be in trouble.

“Visually it looks more like 80% extracted. So I think the chart is a little misleading.”

It’s a cross section, so it’s only showing a narrow strip of the field, not all of it. To get the full view one would have to do a 3d plot of some form.

How many people reading this blog have any contact with or knowledge of Changing World Technologies? (http://www.changingworldtech.com) They make oil. They make oil through a process known as thermal depolymerization. Their joint effort with ConAgra Foods produces 200 barrels a day. Their next plant is projected to produce 500 barrels a day at peak capacity.

Expand this nation wide, with plants capable of producing thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil a day. Millions? How high can production be scaled?

Think of the U.S. as a net exporter of oil. By mid-century our problem could be not a lack of oil, but too much.

One point that many overlook is the importance of a free market for fungible oil.

Consider a country that decided to forego the cheapest oil for political reasons and only use higher price energy sources (say ethanol). Given that energy is really the economic driver for industrial civilization, the country with the high cost energy would find itself at a disadvantage competitively for almost all of its products.

The converse was one of the risks Saddam Hussein poised in his takeover of Kuweit. He would then have such a large market share that he could favor his friends and disadvantage his enemies. Note that Hussein was not an economic actor – his motivations were political. Say he offered to sell his oil for $10 a barrel to his buddies where the market price was $40. Many countries (France?) would grant him ANY political favor he desired. Look at the Food-for-Oil program – how many Security Council votes did he buy?

Revisiting our earlier series on peak oil, Prof. Hamilton asked, if peak oil is imminent, why aren’t futures prices higher? After some thought, I propose a better test of the forward price curve for oil – equity prices for stripper wells. There is an active but fragmented market for older, low flow wells. These often have years of low flow ahead of them so might offer some insight. What price to go long physically?

Note that stock prices for major oil producers are often correlated with equity per barrel of reserves. However, reserve estimates are not in good odor these days, given recent major downward adjustments so this discounts the numbers. Stripper wells at least have a proven track record.

JDH: Nice post. Summarizes well my thoughts on this topic.

Alan Kellog: Biodiesel will likely be an important component of future transportation energy. But people have to eat also. Look at the numbers. The US won’t be exporting biodiesel. Heck, just recently we became a net importer of agriculture. I can quantify my response to disprove your suggestion, but intuitively, I know it ain’t gonna happen.

Alan:

I couldn’t find this information CWT’s page, but maybe you know: what’s the energy balance in their process? If they have to input 1.000001 BTU to get 1 BTU out, the process is an energy loser. It can still be a wonderful and profitable process for them, but it won’t solve anyone’s energy problems.

-mike

It’s possible the Abqaiq cross-section is correct and not inconsistent with the statements as to production. It is not possible to produce all oil in place,for various geological and engineering reasons which are beyond my comprehension. Some claims are made that only 30% of oil in place can actually be pumped out. This is why secondary production methods like inserting water or tertiary methods like steam injection are used,to increase the amount of ultimate production.

Furthermore,just because the oil is there doesn’t mean it makes sense to get it out. These secondary and tertiary methods are expensive. Depending on the price of oil and other considerations,it just might not be worth the expense to do it.

Perhaps a major reason for the decline in U S production is the burden of endless government regulation. We don’t build refineries or nuclear plants and don’t allow drilling anywhere it has been declared pristine. Then we complain that the manufacturing sector is being outsourced and jobs are being lost. At some point all that we could do here in the U S might be deregulated and we will start exploiting domestic resources.

Anonymous poster: You are wrong. Completely wrong. The reason that the US production of oil–and other materials–is in decline is because WE’VE USED THEM. Yes, we can slow the rate of decline by allowing access to additionals sources of resources (alaska, offshore oil) and additional means of extraction (like strip mining).

But please, this particular contribution you’ve made is ideological. It supports a particular group but is not factually based. Let’s start dealing with facts, not ideology.

“Once you look at the details of any particular plan, you will probably end up concluding that, no matter what the cost of oil imports, we are better off just paying that cost and relying ever increasingly on imported oil.” – JDH

Actually, I’d be pretty comfortable with that as a policiy, if it was paired with an efficiency drive (voluntary or directed).

If there is no silver bullet, then efficiency really becomes … the whole game.

Amory Lovins shows us how to get off imported oil in “Winning the Oil Endgame”.

Executive summary:

http://www.oilendgame.com/ExecutiveSummary.html

(no need to download the PDF, just scroll down)

Mr. Norris,

I’m shocked that anyone is giving Amory Lovins any further credence. His “negawatt” idea was used by Enron for some quick money at our expense.

See my debunking of negawatts here:

http://www.energypulse.net/centers/article/article_display.cfm?a_id=488

I guess we shouldn’t hold just one bad idea against the man but of course there was also his opposition to nuclear power and the boondoggle of the NREL.

Sorry but Amory Lovins is right up there with Jimmy Carter as misguided Americans.

Somsel: I think the “one bad idea” concept applies to your postings. As with your Enron parallel for negawatts, your postings are full of loose connections and analogies. Your ideological blinders are certainly showing. Why pick Jimmy Carter? Why not Richard Nixon and his price controls?

Nuclear power is not economic. Without Govt subsidies it would not exist. We also have no credible plans to deal with the waste. I’m not anti-nuclear, but there are still good reasons to be opposed to nuclear power. Nothing you’ve written deals with the many problems.

Nuclear power isn’t economic? I guess someone forgot to tell the French that (75% of electricity from nuclear power). Nuclear power is not economic when you do it the way the Americans have done it i.e. every nuclear plant is a unique design. Americans should adopt the CANDU reactor for example (one of the most efficient and safest designs in the world).

People on this board are debating whether the US has actually hit peak oil? Wow, talk about denial. All that remains in the US are a few undiscovered small reservoirs. There is no possibility of any undiscovered large reservoirs in the US because there is simply no room between the massive grid of existing exploration and production holes for any such reservoir to exist.

As for why you can’t just pump out 100% of the oil in a reservoir. It’s not like it’s a big underground lake of oil. It’s porous rock with oil filling the holes. Like another poster said the first 30% or so comes out easy, but after that it takes increasingly more expensive processes to extract the remaining amount.

T. R.

Obviously, I’m no admirer of Amory Lovins. His negawatt concept flounders on real world issues of accounting and verification, not to mention that it is ultimately coercive against common sense. The Enron example is indeed an example of negawatts and the corruption the concept allows. Don’t think that any implemented negawatt scheme wouldn’t suffer scams of fabricated intentions.

While my criticism of Amory Lovins’ prior work does not encourage me to think that his current work would be any better, it is not necessarily an ad homineum argument. What if you heard that David Duke has published a new work on racial harmony – would you rush to read it? How about Paris Hilton on lady-like decorum? Bill Bennett on dieting? Michael Savage on civility?

Granted, Richard Nixon’s price controls were stupid and unbecoming a Republican. The list of stupid people is endless – sorry that I didn’t guess your personal favorites.

As to the “many problems” of nuclear power, I can only reply that without problems, we wouldn’t need engineers. ALL energy options have problems; maturity is facing them and choosing the least bad option. If you have other specific questions, please write me.

Nuclear waste is the one energy externality for which the end user is charged today. Do we have a greenhouse gas tax? No. For specifics on the Yucca Mountain project, check here:

http://www.ocrwm.doe.gov/technical/index.shtml

Personally, I’m increasingly attracted by reprocessing and actinide burners as a cheaper alternative to Yucca Mountain.

Rather than burying uranium and plutonium, we could provide 10 times more electricity than would the Strategic Petroleum Reserve if we burned it to make electricity. Fissioning of the transuranic waste in actinide burners would both provide additional electric output and would reduce the radiotoxcity, half life, heat output, and volume of remaining wastes by factors of 10X to 1000X.

AND save the US taxpayer $80 billion. Now we only need to convince Harry Reid.

The french pay a staggering fee for their electricity, as most (if not all) utilities are nationalized, and heavily subsidized.

I don’t see the “a 30-year record of declining production” in US oil production. ON that graph, I see it having a slight increase from @1976 to 1985. Seems more like it’s a 20 year decline. And without looking back at oil prices in real dollars seems to fit the big drop in price that we’ve seen over the last 20 years.

Other than nuclear, coal is really the only other choice (wind, solar, etc. have too low of an energy density to ever contribute a significant amount). Using coal to generate electricity is strictly cheaper if one ignores the “hidden” costs (pollution, global warming) which is just a different kind of subsidy.

Allen: I think you make a good point. There were not a lot of incentives to pull oil out of the ground when cheap oil–e.g. OPEC, North Sea, and Alaskan–were readily available. Rising prices may slow the decline (as additional effort is put into extraction of more expensive oil). But my intitution from reading from a variety of sources tells me that we will only slow the decline.

Somsel: I simply wanted to point out a couple issues. (1) Without the upfront R&D that the Govt put into nuclear, it would not exist. There were no economic reasons to sink those costs. (2) The govt has placed control on nuclear liability–not allowing the free market to set these liability prices as it sees fit (3) The Govt is the source of funding for R&D into waste processing and breeder reactors and other next generation technologies.

I just don’t see nuclear as economical without Govt all over the place. Certainly Govt has been all over the place just to get where were are today. It wouldn’t exist without the Govt. The free market never would have developed it what with cheap natural gas and cheap oil.

Explaination of the figure US crude oil production [extraction] 1949-2004:

The slight increase in crude oil extraction from about 1976 to about 1986 was due to additional supplies from Alaska.

Figures which show only the Lower-48 US states show the classic peak-curve. When one examines only the Lower-48 States, then it is very clear that US extraction [production] is past peak. Alaskan oil has it own peak later on, in the 1980s I believe.

T. R.

I would offer that nuclear industrial policy has been one of the most successful that our government has undertaken in its history, comparable to the transcontinental railroad. Today, nuclear power is a big cash cow for taxes and, I suspect, more than paid back early R&D efforts. I’d love to go back to grad school and do a thesis on this! The national security implications of no longer needing imported petroleum to fuel 35% of our electricity production, as we needed in 1970, certainly has value too.

Note that the one mill per kW-hr nuclear waste “trust fund” tax more than funds current government Yucca Mountain work – the “left overs” go to the Treasury. Local property taxes also mean well-funded school systems at nuclear plant locations. Lord knows that I pay enough income taxes off my nuclear work income! That said, I’m not a defender of the Energy Bill’s nuclear production tax credit. Ian has it right.

The problem with “nuclear liability” might well be better cast as a problem with trial lawyers and the tort system. Reasonable estimates of the economic consequences of nuclear plant accidents exist and those can and are privately insured. Following TMI, people were getting money thrown at them because they were “frightened.”

Frankly, nuclear power would be much MORE competitive without so much government interference and regulation. We still need competent regulation and I think that Nils Diaz at the NRC has been a big step in the right direction.

As to French electricity rates, I would appreciate any input from other readers on the residential rates to the customer – I’ve never bought electricity in France. Here in Northern California, Pacific Gas and Electric charges me about 20 cents a kW-hr on the margin. Some of that is hidden taxes. The wholesale busbar cost for its nuclear power plant, Diablo Canyon, is about 2.8 cents per kW-hr according to the last CPUC filing I saw. That’s the cheapest year-round power source for the system.

As Amory Lovins, the soft energy guru who directs the Rocky Mountain Institute, a Colorado think tank that advises corporations and governments on energy use, points out, “Nowhere (in the world) do

market-driven utilities buy, or private investors finance, new nuclear

plants.” Only large government intervention keeps the nuclear option

alive.

http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2005/08/07/ING95E1VQ71.DTL

Seconding muhandis’ post above. Oil production in the contiguous US did peak around 1970. With the discovery of the Prudhoe Bay fields in Alaska, Overall US production increased, but lower-48 production continued to fall.

We actually pumped Prudhoe Bay faster than we’d planned, and it reached its production peak years before it was supposed to.

(sorry, no refs — they’re hiding and I’m lazy)

-mike

I believe the rates that are commonly reported for nuclear power do not include the actual cost of the construction and decommissioning of the power plant, only the current operating costs.

Detailed debates on nuclear no doubt should be held elsewhere. I’m primarily interested in pointing out that nuclear would not exist without govt intervention. And that there are a lot of uncertainties associated with nuclear. The US has existed for approximately 225 years. Many of the products from nuclear must be controlled and monitored for over 500 years (in the best of cases).

Somsel makes it all sound simple. It’s not. Without overt and rather extravagant govt intervention, nuclear would not exist. The market has certainly spoken on that one, similar to the way the market right now is pushing oil up towards $65/barrel.

One clarification on my comment that increased prices would slow the decline in the US production. Increased investment in US fields MAY slow the decline for a time, but only by increasing rate of fall-off in the future. The decline will slow for a time, then rapidly fall. The curse of improved extraction technology. It makes the market think everything is cool until the bottom falls out.

Re: comments by Joseph Somsel:

“…The converse was one of the risks Saddam Hussein poised in his takeover of Kuweit. He would then have such a large market share that he could favor his friends and disadvantage his enemies. Note that Hussein was not an economic actor – his motivations were political…”

My recollection of Hussein’s motives is different. Iraq was bankrolled by the Gulf kingdoms to beat-up Iran following the overthrow of the monarchy and the set-up of a republic. The five year war was a stalemate that bankrupted both Iraq and Iran. In the end, Iraq was left owing huge sums to its creditors, the Kuwaitis were one of the principle creditors.

Following the downturn in the price of oil (some say as a result of Saudi oversupply to weaken the foreign exchange revenues of the Soviet Union), Kuwait needed to call the loans. Iraq had two options — default or annex Kuwait.

I still recall the news after the invasion, the US confirmed that it would not interfer in the affairs of Iraq and Kuwait. I guess the Kuwaitis may have owned more assets in the US than the Iraqis.

http://www.cbc.ca/news/background/iraq/index.html

Another great post, with excellent comments. However, I think that another detail is also important: transportation is absorbing roughly 2/3 of the oil we use (check the “Oil market basics” page at the DOE website). To what extent our economy is dependent on cars and trucks ? Can we quantify the effect of rising transportation costs on the economy? Isn’t nuclear energy and coal irrelevant for transportation?

Coal can be processed into liquid fuels. Increasing nuclear would decrease the amount of coal and natural gas burned. So both coal and nuclear help soften the blow.

Note that oil is used primarily as a transportation fuel while coal and nucs are used to generate electricity. There isn’t a lot of interchange between the two with today’s technology.

Also, as noted above, the increase between 76 and 86 was due to Alaska. If the industry were permitted to look in additional areas – offshore California and Florida – we might just see that increase again.

Getting back to Prof. Hamilton’s question, “..what happens when we experience on a global scale the same depletion that’s occurred in the United States…”

I beleive that the answer is partly bounded by the rate at which world supplies decrease. But with respect to the economy, isn’t there only one of three possible short-term outcomes?

1) ration the petroleum, keep prices stable;

2) decrease demand by decreasing economic activity (raise interest rates?)– prices stable; or

3) let demand destruction occur in response to increasing prices.

However, what happens when geopolitics are added to the mix? An ‘orange revolution’ here, and an invasion there: such things complicate matters. I suspect that any economic model or theory will be utterly distorted by the geopolitical games which are already well underway.

Muhandis: My uneducated (economically uneducated at least) intuitive prediction is a set of shocks. Growth runs into a ceiling (an energy constrain ceiling) that results in demand destruction. I think geopolitical games (including warfare) will be modulations of the overall theme: hit the ceiling, demand destruction, global imbalances unwind (e.g. enormous trade gaps), oil become cheaper, growth gets going again, hit the ceiling again, and repeat.

I see no other option. I see no miracles over the horizon. But I see this playing out over decades. There are some in the peak oil community (many I think) who believe industrial civilization will collapse tomorrow. I see that as unlikely. More nuclear, more coal (and attendent global warming), more opening up of oil in places like offshore CA. But it will be messy.

No miracles. I think there is an important need for a modelling effort that combines economics with a model of energy flow through the economy so people can get their hands around this problem more adequately. The analogies, internet debates, and ideologically entrenched positions make progress difficult without more concrete systematic modeling.

Bring it on, Mr. Elliot and Mr. Norris, et al!

Here’s a cost breakdown for new nukes v. LNG electricity:

http://www.energypulse.net/centers/article/article_display.cfm?a_id=623

Nuclear waste and decommissioning are indeed built into the cost although they are chump change in the Big Picture. Note that I screwed up at first by using too high a CCGT heat rate but recalculated it with a modern number so see the comments for corrected cost differential summary. (Hint – nuclear power wins.)

Current costs for paid-off nukes ARE pretty darn good! But then, so is the roof over your head once your mortgage is paid.

As to “free market nuclear power”, just try opening a uranium mine or buying a ton of yellowcake without a government permit. Touch the controls of a nuclear reactor without a personal nuclear reactor operator license and you are a felon and they’ll make a Federal case of it. To see what the bureaucrats can do to private nuclear enterprise, read the history of the Fermi I power plant published by the American Nuclear Society. Yep, we’re in bed with the government, for better or worst.

The alternate histories of nuclear power from the reality of WWII and the US government could go many ways. Mr. Elliot and Mr. Lovins thinks nuclear power would have been stillborn. I think that it is just as likely that we would see greater nuclear market share today. We’ll never know.

I haven’t a clue about Saddam Hussein’s motivations for his wars; I do know that his power over increasing amounts of Persian Gulf oil should have scared the bejeezus out of every free government on the planet. Bush 41 certainly found Gulf War I an easy sell.

Of course, Mr. Anony Mouse is correct – oil and nukes don’t directly compete today – nukes drove oil-fired electric plants from the market during the late 70’s and 80’s. But there is cross-over – double the price of electricity to power the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) and fares will increase. Hold electric power costs constant and double gasoline prices and ridership will increase. Longer term, increased electrification of transport due to Peak Oil is predictable and nuclear is the key to a “hydrogen economy” and those cute fuel cell cars Arnold likes to pose with.

My biggest concern professionally is not Peak Oil but Peak Natural Gas. Building natural gas fired electric generators today is folly since gas will peak before the plants are paid for.

You guys are great! Best comment group on the Web. Thanks for hearing me out.

So T.R. Elliot, your’re opting for case 3, let demand destruction occur in response to price rises? It seems like Darwin would approve, and it also seems most likely to me — at least in the broader sense.

I agree, it will likely be a roller coaster. We might get a glimps of this pattern this fall/winter, but with North American natural gas.

I think “demand reduction” is a better term than “demand destruction”. We don’t speak of “supply destruction” when prices fall. Standard supply-demand curves show that demand is reduced with higher prices and increased with lower prices. There is no “destruction” involved.

The biggest impact may not be the direct consequences of high oil prices. Look at what happened to productivity from 1974 to 1995 —

it fell from the long term rate of around 3% to 1.5%. I suspect the primary reason for low productivity over that era was the major shift in the nature of investment from targeting labor productivity to targeting energy conservation.

As we start to react to higher oil we are likely to see a similar shift in the nature of investment and a sharp slowing of productivity growth and improvements in standards of living.

Hal:

Good point, demand reduction. It is a clearer term.

Perhaps we should also consider petroleum extraction instead of production? It is essentially a form of mining and not the same as widget production.

1. Why doesn’t the U.S. Govt./states stop collecting taxes on gas sales over $1.85 per gallon 2. Why doesn’t the gov. control prices of oil by releasing reserves and flooding the oil market? And last. What a lot of bull when the oil industry says it will take 10 years to build an oil refinery. Remember the liberty ships that were built at one per week? Why can’t many companies build components to be put together on site. What is an oil refinery nothing more than a bunch of pipes.

“Why doesn’t the U.S. Govt./states stop collecting taxes on gas sales over $1.85 per gallon”

Because that would further subsdize driving, which is the last thing a sensible government would want to do now. As it stands, the gas tax would need to go UP about another 50 cents a gallon just to cover the direct costs of roadway construction and maintenance currently borne by a combination of the existing gas tax and non-user-fees like property and sales taxes.

Joseph,

“Current costs for paid-off nukes ARE pretty darn good!”

No. Just, No.

Not even close.

If you handwave away the problem of nuclear waste and decommissioning, even then: No. Just, No.

I refer to our own utility’s experience with the “too cheap to meter” electricity from the South Texas Nuclear Project. Suffice to say, we’re metering it, and it ain’t cheap.

M1EK,

So you respond “No. Just, No.”

I guess that settles it.

BTW, “Too cheap to meter” is a quote from a FDR socialist. Plus, meters were more expensive back then. South Texas Project has had a checkered past, no doubt.

Mr. Spenser,

Good point about productivity droop although the capital didn’t necessarily flow all to conservation and efficiency. We also had to rebuilt our electric system so nuclear power plants sucked up a lot of that capital.

In fact, productivity in most of US history has been correlated with increased energy substitution for labor. Maybe “amplification” is a better word.

The latest boost has been due to our investments in computers, telecommunications and the internet, IMHO. Suggest you read some on long business cycles, especially their technology drivers. Current theory would suggest that productivity gains over the next 20 years will be slower but that the gains will diffuse out to the general population. PO will change that, I bet.

As to Muhandis’ scenarios, I’d predict huge inflation as oil consumers race to cheaper the currency for which the oil is bought with. That will also cut consumption for oil and for everything else in our economy that has an oil input. Capital will have to flow to alternatives to oil and since non-oil has a lower EROEI, more of it will be needed per unit consumption. Other users of capital will be starved. That’s a replay of the 70’s and early 80s. It might be different this time.

Thanks for using us as an example. To condense some of the data from our site for your readers. Here is the current situation – Saudi production from existing wells is declining at 1 mbd per year and must be replaced, Russia has said that exports from there cannot increase, the North Sea is declining at 500 kbd per year. Mexico has peaked and is in decline – and I could go on, but the point is that the data suggest that the crunch point is closer than you realize, and that demand destruction due to price is already occurring.

I’m a consultant weenie, not an econ jock. But I’m dissapointed that all the discussion is about market guess of oil reserves versus actual. How about cartel dynamics of OPEC?

I have a small question.

Why do people think $60 per barrel is low, when Peak Oil is almost here? I think $60 per barrel is a very decent price, to set up for a 3% reduction per year as depletion dictates.

Now here is my reasoning:

Lets say oil is 60$ a barrel. Lets also say the price will rise with 8% per year, a decent economical profit. That will put oil at 90$ a barrel in 5 years. Lets also say that the (short term) price elasticity of oil is 0.4, i.e. 1% rise in price reduces the demand for oil with 0.4%. This is not a scientific fact, more a ‘surf a lot and this number pops up’ number. But just for arguments sake.

This will reduce demand with some 3-3.5% per year, next 5 years. In line with the depletion numbers.

Now, after 5 years, the price elasticity should be better. People will start buying smaller cars etc, carpool a bit. You know, the works.

When oil is 90$ a barrel, reduction in use of oil is no more an option, it’s a fact. See the oil shock in 1980. Because it was done then with a shock, a recession came, but afterwards. We are now at 60$ a barrel and every year, we will add 10$ more. Demand will reduce, but a recession will be less clear.

So why is the economy not tanking right now? Because there seems to be a lot of ‘low hanging fruit’ laying around. Stuff you can easily do, without much impact. And keep in mind: the economy as a whole is maybe not tanking, but the horsemen of depletion are: GM, Ford. Only Toyota is doing ok. And why is that? This argument is not completely fair, but you get my point. People are already changing.

So what do you think? Maybe 60$ a barrel is not so unlogical after all.

Regarding the comment from OilDrum: “…but the point is that the data suggest that the crunch point is closer than you realize, and that demand destruction due to price is already occurring…”

The August ASPO Newsletter indicates that conventional world petroleum extraction peaked in 2004. Colin Campbell and colleagues estimate combined peak (conventional and hard to get at oil) in 2007. Chris Skrebowski (Energy Institute UK) estimates about 2008 (as of April 2005) based upon mega-project count and current depletion rates.

I believe that if the world economy keeps humming along, then they will be correct, and the scenario ‘big prices until demand reduction occurs’ will play-out. However, if the world economy slows down (drop in demand) then the peak will be pushed out later–but not too much later.

Given that it takes 4 to 6 to develop a new mega-field, we will hit some sort of peak. The question is whether its cause will be infrastructure/investment or geologic. It is the geologic peak as provided in the example of Lower 48 USA plus Alaska which is the crux of peak oil.

I believe that OilDrum is correct in that demand reduction is occurring, but not yet in the wealthiest nations.

So, if the peak is within 2 to 3 years, one might expect the market prices to be factoring in respective risks. Maybe they are, and that is what is confounding many market analysts.

I wanted to touch on a couple of points raised in the above.

Several people pointed out the rise in the US production in the late 1970s and 1980s. This was due to the discovery of the Alaska fields (which are now themselves in depletion). Along with the North Sea, this has a lot to do with why the energy crises of the 70s went away for a couple of decades. It may be there will be another small peaklet soon due to deep water Gulf of Mexico oil, or maybe not. However, the chances of returning to 1970 production is negligible.

The inconsistency between the Abiquaq picture and the 50% number may well be a real inconsistency. The Saudis quoted their reserves at around 160 Gbarrels in the early eighties, suddenly increased them to 255 Gbarrels in 1986, without announcing any large discovies, and have kept them essentially flat ever since. OPEC quotas are proportional to reserves and most OPEC nations followed a very similar pattern of reserve boosting within a few years. It seems rather unlikely that they were telling the truth, and the true state of their reserves is rather unclear. If you want to see the history of their claimed reserves, check out

http://www.bp.com/downloads.do?categoryId=9003093&contentId=7005944

(grab the spreadsheet version for easy charting and look at the “Oil – Proved Reserves History” tab).

Several people suggested biodiesel as a significant part of the answer. This is thermodynamically/ecologically implausible. Substantially more than half of all global photosynthetic production is already diverted to human use in one way or another (see Vitousek et al Science 277:494-499 (1997)), and with population and economic growth as it is, that will be almost 100% pretty soon. So the output of photosynthesis is already spoken for, and using it for transport would have to displace something else (eg food or building materials). Not only that, the fraction of energy available via global photosynthesis is quite a bit smaller than we use via oil already.

This is intuitively obvious – the last time transport was funded entirely out of biomass was in the late 1700s, early 1800s (horses pulling carriages and canal boats). Population was less than a billion, and regular famines kept it in check – the earth was close to carrying capacity for biomass based technology already at that time. It should be obvious that supporting 10 times as many people, with a significant fraction using 200 horsepower vehicles instead of one horsepower horses, is not going to fly on the same fundamental energy support as in pre-industrial times (unless we make plants with much better photosynthesis than the ones that evolution has managed to come up with).

This is where the more terrified sections of the peak oil community are coming from: very rapid drawdown of fossil fuels has permitted an expansion of human population and economic activity to a couple of orders of magnitude over what would be feasible in a pure biomass based economy. Now we have to start thinking about how to keep that going in a civilized manner post fossil fuels (albeit that coal gives us a gentler tail-off if we don’t mind the funny weather).

Stuart.

…and it was suggested to me that the difference between commodity scarcity and crisis is that in a scarcity the price becomes very, very high. While for a crisis, price is irrelevant–it cannot be had at any price.

The terrified sections of the peak oil community see crisis while other peak oilists see scarcity. However, the second half of the petroleum age will be of scarcity, not crisis. Crisis (as defined above) occurs at its end. It is the question of when is the peak that tips the world into scarcity.

Of course, if biohydrogen actually can be genetically engineered, then it is a different matter (biomimetics of photosynthesis for hydrogen production). Even it is a long shot, the Russians, Swedes, Brits, Germans, and Americans are at least giving it a try.

Stuart: I’m with you and with those members of the peak oil community who are concerned about overshoot. I read Catton’s book (Overshoot) a few months ago. I think he makes a good argument that humans are in overshoot. In the long term, e.g. 100 years, I’m not convinced, without the easy energy of fossil fuels, that humanity will be able to maintain these numbers. The physicist Bartlett also makes a good argument about the impossibility of long-term exponential growth.

For me, the real question is what the transition will be like. How will humans manage this. My rants against economics and economists that occur from time to time are primarily directed at ideologues who won’t admit that demand destruction, including death, is an essential component of economics–the ultimate form of demand destruction. There are cornucopians, libertarians, and conservative free marketeers who firmly believe that the invisible hand will lead to “good” but they never bother to define exactly what this good is that we are headed towards. This is not an argument against economics, nor free market economics. It is simply a recognition that oil depletion could very well change the rules of the game.

That is why more detailed modeling and analysis are needed. The radical corner of the peak oil community is filled with survivalists. They’ll look for any excuse to run to the hills. The radical cornucopians, on the other hand, believe all is well: “What, me worry?” The risk and costs are significant enough that a dedicated research project should focus on the implications of peak oil. I know that a university in the South (I forget who) has created a program to evaluate alternative fuel technologies. It seems to be that a companion program should be created to (a) model the flow of energy through society and (b) incorporate energy depletion and the costs (capital expenditures, etc) of rolling out alternative technologies. E.g. answer the question: how fast can hybrids be rolled out, and what difference will it make? What are the implications of creating car pooling programs in the cities and suburbs. Stuff like that.

In summary, I believe we have major problems coming in the next twenty years (through 2025) and potentially catastrophic problems by the middle of the century.

T.R:

I should stress that I don’t take a position at this point on “Overshoot” style issues (I read it recently also). I see too many uncertainties – we don’t really understand what the post-peak depletion rate will be, and we don’t understand the possibilities for innovation in solar capture – Catton dismisses the possibility very cavalierly. I don’t even understand the energetics of most of the existing options terribly well yet (most of the references I’ve found so far are rather old). However, most of the currently known alternatives appear to have bad EROEI, or at least long lead times (like nuclear), meaning they suck as oil substitutes in rapid depletion scenarios.

I do agree with your call for better modeling. There has been a whole science of net energy analysis. See

http://www.oilanalytics.org/neten/neten.html#measure

for a nice introduction to the issues (that I just discovered).

Stuart.

Economics tends to assume smooth transitions: the Hotelling Resource Exhaustion model, where price rises smoothly and backstop technologies come into play.

The reality is likely to be messier: Deffyes makes the analogy to queuing theory when the queuing system is at close to capacity (think a crowded airport or freeway on the Friday before a long weekend). Delays (call them price spikes in an oil system) occur randomly.

The normal transmission channel is via the transport industry. Oil prices spike, and a lot of industrial and distribution capacity needs to be restructured. GM cannot simply switch to making ultra efficient cars overnight. This is pretty clearly what happened in the 1972 and 1980 oil shocks, with the downturn in the auto industry feeding through the rest of the economy.

The auto industry is relatively less important now. But it’s a lot harder for WalMart or Home Depot or other artefacts of the service economy to make rapid changes (you can’t just move stores that are dependent on consumers who drive, and distributors who use trucks). Public transport basically doesn’t exist (less than 5% of all journeys).

My hypothesis is $100/bl gets felt first by the airlines and the hotel and leisure industry (people give up on discretionary trips, even business trips).

What can we do? Well half of new cars in Europe in 2008 will be diesel, which is a 40% fuel economy improvement over a gasoline car. With changes to US clean air regs and improvements to refineries, that can be achieved in the US too. The average fuel economy of US cars is something over 10 mpg less than European or Japanese cars.

There are other ‘quick wins’ of that nature, plus long term shifts in habits (eg working from home 1 day per week).

Beyond that you are in the land of alternative fuels. Natural gas is an obvious one: high use urban vehicles like buses and delivery vehicles can be shifted over. But the price of gas will rise in complement with the price of oil.

Alternative energy it gets harder. Oil sands work, but they burn huge amounts of gas and water to produce. I doubt Alberta can produce more than 3m bl/day of oil sands– useful, but only enough to replace what Canada already produces conventionally.

The hydrogen economy would be a huge government funded project to build the distribution system. And it really doesn’t make sense unless you have a secure way to produce the hydrogen: for which nuclear fission is almost the ideal (but not cheap). Solar is a long way from being a competitor technology and wind is too unreliable– it will only be important in places like the Great Plains where the wind is fairly constant.

I think the bottom line is we can make the adjustment, but the costs will be substantial: perhaps as much as 5% of GDP devoted to creating alternative energy sources, for as much as 30 years. Eventually this *will* happen but I don’t think it will happen before the crisis gets very bad.

Politically, and economically, it is easier to send troops to the Persian Gulf to secure the sacred right to drive SUVs.

As usual, Stuart has a very insightful analysis, one with the ring of truth.

The ramp rate for new nuclear power is a problem I’ve been considering with my colleagues here at VBM (Very Big Multinational Corp.) Just how fast could the world economy build new nuclear power capacity?

Today, we spend two or three years doing studies and haggling with the lawyers before we get an deal signed. We can apply off-the-shelf plant designs but each site is different and requires incorporation of unique local conditions (does the heated cooling water come out of the same or different side as the cool cooling water?) The biggest problem is that every utility is different. Since he who holds the gold, makes the rules, they usually get what they want.

Once the basic design is agreed to, major pieces are ordered – the reactor vessel and the main steam turbine are the biggest with longest lead times. Staff-up then begins with maybe 2,000 trained professionals involved at peak throught the supply chain.

Today, we could start on maybe 8 to 12 sites with two reactors each, worldwide (this is an off-the-top-of-the-head number) for 30 GWe to come on-line in 5 to 10 years. (That seems low!) We could increase that rate as more engineers and technicians became trained and experienced and the major, specialized fabrication facilities expand their shops. In the US, there used to be 4 reactor vessel fabricators – today there are none. These places are big but not all that expensive so once there is a market, hardware production can ramp over a few years.

Uranium supplies just need a solid market. There is plenty of resource that just needs a go-ahead to build mines, ore mills, hexafloride conversion, enrichment plants.

Frankly, my colleagues are worried – we’re really going to have a LOT of work to-do! People may be the tightest constraint.

Peak Natural Gas doesn’t get much consideration but it should. We are already racing to drawdown reserves of NG – with PO, the LNG business will rapidly bloom but just as quickly fade – I see a 10 to 20 year cycle at best. The good news is that we have a viable substitute for NG today – electricity from nuclear. Gas-to-liquids (GTL) is a next tier oil substitute and is a better use of natural gas than LNG-to-CCGT-to-electricity that many are planning on for future generation.

BTW, with the signing of the Energy Bill, VBM management is throwing a picnic Friday for the employees – roast pork and gravy.

I think that history has shown that the cartel and it’s level of effectiveness had a large role in determining price at different times in the past, so that one should at least think about the cartel (how it can be more/less effective) within one’s thinking about the geoligical truths and the market reactions/predictions. For instance, if the cartel is having a significant effect (not saying this is the case, but if), then a small amount of swing production (ANWAR) might be improtant not because it has so much volume on its own, but because it drives cheating and cracks the cartel. Similarly, if we are running out of oil or are even seen to be running out of oil, that might strengthen the cartel. I don’t know how this all plays out, but I think it’s a factor that needs to be considered.

I liked the post about 60 dollars maybe being a reasonable level given the expectation of raises with time. I don’t know how, but I would think examining the value of different futures of different maturity might help evaluate this argument.

I think that it is very possible to be a hard corps free marketer, without beleiving that the market will come up with a magic science fix. After all free markets don’tm trump physics. That does not mean that government programs are the right answer either. Maybe just letting things unfold is the most efficient response.

I mean if the market can’t come up with a magic science fix (e.g. efficient photovoltaics), what makes you think the government will? Now some things to consider are effects of patent life, etc. (perhaps the market can’t capture the value of research…I fear we may be heading this way in pharmaceuticals) Also, one can consider government actions that enable production (e.g opening ANWAR, making it less litigious to build a nuke plant or a refinery, etc.)

JAKARTA (MarketWatch) — Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s sole member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, will be a net oil importer in 2005, Coordinating Minister for the Economy Aburizal Bakrie said Tuesday.

“South Texas Project has had a checkered past, no doubt.”

That’s understating it. I see no evidence that any vast improvement has been made in nuclear plant technology to prevent the overruns, mistakes, and shutdowns which have so far made the electricity out of this project ‘too expensive to meter’.

Ironically, our local political paper thinks our reliance on the STNP is a good reason to push wind and solar — because the outage a couple years ago caushed a sudden uptick in spot prices (most of the cost of the STNP is now sunk; when it actually WORKS, the electricity coming out is in fact cheap). The ‘green rate’ that you can lock in is actually a hedge against buying natural gas on the spot market the next time the nuke breaks down – the people buying wind/solar actually are paying a slight premium for the assurance that they won’t get screwed if the outage happens again.

M1EK,

Looks like STP-1 had a rough year in 2003 – a capacity factor of 62.6% is well below current industry average. Of course, for both reactors combined, 2003 had a PLANT average of 72.5% – decent but not stellar and above the planning assumption of 70%.

2004 looks much better – Unit 1 ran at 101% of nameplate capacity. Unit 2 must have had a refueling outage because it was only 93.8% for a plant total capacity factor of 97.4%.

In comparison, windmills have a typical US capacity factor of roughly 25 to 30% according to EIA.

Plus, I see that STP had the LOWEST fuel cost of any thermal power plant (nuclear or not) in the whole USA in 2001. Also, in 2001, STP-1 made more kW-hr than any other nuclear power plant in the country.

If you and the Austin newspaper are complaining about STP’s overall performance over the last few years, you’re either spoiled, ignorant of the real-world energy business, or willfully ignoring reality for your political ideology. That said, diversity in power supply is a good thing in general.

In fact, US nuclear performance has made tremendous improvement – I know because I’ve been in the thick of it for 30 years. For the facts, check this:

http://www.nei.org/documents/U.S._Nuclear_Industry_Capacity_Factors_1980_2004.pdf

New plants have incorporated all we’ve learned. Today they have fewer pipes, better controls and instruments, much better man/machine interfaces, improved materials, more experienced engineers, better trained operators, and wiser management.

The record clearly shows this. Nuclear power has delivered on its promise and is ready to do more for humanity’s energy needs.

*insert Navy Nuke sneer at civilian power*

John,

“If you and the Austin newspaper are complaining about STP’s overall performance over the last few years”

I was clear that it was the sunk cost (via overruns, delays, etc) that was killing the STNP’s supposed economies of scale, not the current operating cost, which I said explicitly were quite low.

However, the guess (at least in that particular article) is that the plant only has another 10-20 years left of useful life before it needs to be substantially refitted – and given the recent outage, there’s some question whether it will EVER pay back the sunk costs and come in with an OVERALL cost lower than wind.

Doesn’t matter what the capacity factor of West Texas wind is – what matters is cost per kwH, and we know that’s just a bit over NG now. Cost per kwH of the STNP can’t be figured accurately until the useful life of the plant is determined, but it doesn’t look so good.

As to an earlier comment by Lovins about there never been a private financier of nuclear power, how about Warren Buffett?

http://www.nei.org/doc.asp?docid=1407

STP-1’s operating license expires in 2027 and STP-2’s a year later. Then they can go for 20 year extensions. The waste costs are covered in the Nuclear Trust Fund tax and the decommissioning costs are covered in a decommission account under IRS, state PUC, and NRC supervision. That latter costs have been trending downward with better experience and techniques.

STP’s construction problems included willful, criminal (IMHO) extortion. The insider story was that a quick way to pickup $50k was to fabricate a “defect” and turn whistleblower then negotiate a payment from the utility to drop the issue. I argued for indusry support for a NRC regulation to prevent this practice. NRC inspectors were being physically attacked on site. Itinerent political hacks were grandstanding for news exposure. My question is, was this due to nuclear or due to Texas?

As to the question of population/energy overshoot, I too am concerned. However, my digging into non-conventional oil has been encouraging – it will still be a problem but there is more transport fuel resources available at a higher price or EROEI tier. It won’t be easy but I intuit that it’s doable. Combining those new sources with carbon dioxide issues will be the very hard part.

Here’s an appropriate article for this particular thread. Found it at peakoil.com:

http://321energy.com/editorials/bainerman/bainerman081005.html

The usual discussion of agriculture, transportation, and impact of peak oil on money, interest rates, etc. Speculative (isn’t most economics?) but also worth a read.

Joseph,

You’ve continued to ignore the ‘sunk costs’ of the STNP, which, even if it operates at 100% capacity for the remainder of its life, make it unlikely its overall average cost will be low. IE, if everything from here on out goes perfectly, a lot of folks still think the overall cost is going to be a lot higher than ‘too cheap to meter’.

Also,

“My question is, was this due to nuclear or due to Texas?”

You’d be hard to find a state more likely to roll over for nuclear interests than Texas. I find your conspiracy theories very unlikely given the incredibly pro-development political landscape here.

I don’t pretend to fully understand the nuclear option at this point, and especially not the conversion to a transport fuel (is hydrogen really competitive with lead acid batteries?). But there are two things that make me pretty nervous about it as a solution to peak oil. One is the long lead times issue Joseph addressed above. That’s not so much of an issue if depletion is slow (a few percent annually), but it’s a very big issue if depletion is fast. Consider that UK North Sea oil is now depleting at 10-15% annually. Mexico projects doing the same shortly. Consider the worst case in which the whole world ends up depleting like that — say 10% — after all this high technology has been applied to suck out the last oil in the fields very rapidly. Now seven years to build a generation of nuclear plants becomes long enough for oil output to have halved. And will halve again while the next generation gets built. (I’m not saying this is the likely case, but it’s sort of the Worst Reasonable case). That doesn’t sound too good.

However, in a slow depletion world, nuclear plus plug-in hybrids sounds good for a century or so, except for the security issues. I’m willing to believe that existing experienced staff at major western companies can build a safe plant. But that just gets us the first few plants, after which the plants are going to be built by inexperienced staff, not all in western companies.

Take India, which the US has just agreed to help with building more nuclear power plants. I’ve spent a lot of time in India in the last few years. It’s a great country with a lot of tremendously talented people. However, like a lot of developing countries, it has extremely corrupt bureaucracies. See

http://www.globalcorruptionreport.org/

So a rapid ramp-up of nuclear plants means building lots of them in developing countries, with inexperienced engineers (since personnel are limited), and a lot of corruption. Developing country building contractors tend to do things like cheat and leave half the rebar out of concrete to save money, or deliberately make the roadbed too thin so they get to fix it again in a few years. And yet we need to be certain that nuclear materials don’t go astray and that none of these plants melt-down. Chernobyl makes it clear what the consequences are for getting it wrong. Whether it’s better to accept a Chernobyl every decade or two, or deal with the climatic consequences of burning all the coal, I think is rather hard to say.

And then there’s the likelihood that states with a nuclear fuel chain will decide they’d like some weapons too, and the risk that sooner or later some will end up in the wrong hands. We’ve already seen what Pakistan managed to achieve with its nuclear industry. I think it’s clear that if Al Qaeda ever gets nuclear weapons, they will use them.

So I guess I’m not convinced that there’s really a scalable global solution here, at least not at this point, despite the fact that the US civilian industry has really a pretty good operating record recently.

I guess in the final analysis, nuclear technology is the one energy option we have that actually has some not-completely-negligible risk of eradicating the species, rather than just failing to protect us from a time of hardship and, in the worst depletion scenarios, reduced numbers.

Stuart.

Isn’t the problem before us how to deal with peak oil (and peak natural gas)? Isn’t the responsible position to honestly consider more nuclear power as an option and to offer constructive suggestions as to how to make it a better contributor?

If every argument from this admitted proponent of nuclear is evaded and every factual presentation dismissed, then you’re not contributing. If you really believe I’m an untrustworthy liar, spinning conspiracy theories, just because I’m pro-nuclear, then ignore my postings. I’m taking a lot of my time to share my 30 years of real-world, hard won, experience in the energy busines with you. No one has claimed that nuclear is perfect and that we couldn’t have done some things better.

Mr. Elliot claims that I “make things sound so simple.” Is that a complaint?! I consider my postings as a public service – I think hard about how to distill a complex situation into jargon-free terms that convey the truth of the matter at the public policy level. I also express confidence in my colleagues’ ability to continue to improve the technology and to overcome substantial technical challenges (such as molten lead actinide burners.) Too bad if that flies in the face of politically correct moral posturing and defeatism.

We’re all in this together. Let’s start working together.

Joseph:

I for one have learnt a lot from your postings, here and elsewhere, and value them. But you’ve got to realize much debate needs to happen over these issues, and no-one is going to be persuaded of anything quickly. There’s value for you in understanding what it is that makes others uncomfortable about the nuclear option.

Stuart.

I don’t hate nuclear power so much that I’d oppose it, but I don’t love it so much that I want to get in line to support it either. I sort of feel that if it becomes a necessary thing, it will have enough supporters.

I’d much rather talk about how soon we start conserving, which is why I picked up on that one line from the original article in my post above.

Gas is $2.65 in Orange County, Californa … are we conserving yet?

We have about 50 years of nuclear fuel remaining

This is not a solution to our energy problem.

To use plants to create fuel would result in dedicating 3 midwest states to the production of plants for ethanol. This does not work

We have about 1 trillion barrels of easy oil to pump in the world

We have about 4 trillion barrels of hard to process oil from oil shale and tar sands located in North and South America.

My Question: how much does the hard to proces oil cost per barrel??

If we fully utilize our great plains wind energy, how many giga watts would be produced?

The electricity could be used to create hydrogen.

Yes, the U.S. shifted to foreign supplies as we depleted our own supplies because over the last century as their was no better solution. The difference now is that the world is undergoing a global demand shift for petroleum as China and India industrialize and millions of are cars enter their roads for the first time. (Visit these places and see firsthand.) Continued price increases will bring about a substitution effect as technologies evolve and become inexpensive compared to petroleum. Higher petroleum prices will ensure that the world never runs out of the dirty stuff. Would any of you drive a gasoline powered automobile were a gallon of petro to cost $100 in real terms?

Nobut we may drive a horse and buggy and that wouldn’t get me home to my parents on holidays.

To Observer:

You assert:

“We have about 50 years of nuclear fuel remaining

This is not a solution to our energy problem.”

However, the Australians look at it differently:

“(E)nough to last for some 50 years. This represents a higher level of assured resources than is normal for most minerals. Further exploration and higher prices will certainly, on the basis of present geological knowledge, yield further resources as present ones are used up. There was very little uranium exploration between 1985 and 2005, so a significant increase in exploration effort could readily double the known economic resources, and a doubling of price from present levels could be expected to create about a tenfold increase in measured resources, over time.” (See http://www.UIC.com)

This analysis ignores the Megatons-to-Megawatts program that supplies 10% of US electric fuel (half our nuclear fuel needs) and should for several years to come. I suspect the Australians rue that one.

In summary, shortages of uranium are not to be expected for hundreds of years, even without breeders. Nuclear fuel is not an issue in the current debate over new nuclear plants.

I’m a latecomer to this debate, but I am amazed by the extent to which the discussion of peak oil has veered off onto barely relevant tangents.

Oil consumption in the United States is overwhelmingly for use in transportation fuels. Some aspects of that are quite important (e.g., delivery of food to cities) but all of it could be replaced by much more efficient alternatives with relatively little disruption.

The US private care fleet is vastly larger than any other country’s, and vastly less efficient. Just replace every car on the road with a hybrid, and watch oil demand fall faster than supply. As the price of oil and gasoline rise, the market will take care of the problem by encouraging people to switch to more efficient forms of transportation. Some people will even switch to bicycles for short shopping trips. This will not cause a breakdown of civilization.